Symbols of the seasons (Symbole pór roku)

Autor Old European Culture ©©tłumaczenie Czesław Białczyński

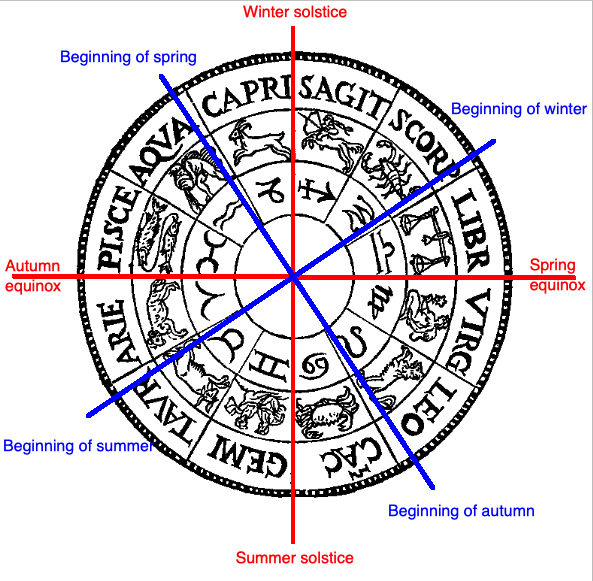

If we look at the zodiac circle, we can see that each of the seasons either starts or ends with a sign representing a large animal:

Jeśli spojrzymy na okrąg zodiaku, zobaczymy, że każda z pór roku zaczyna się lub kończy znakiem przedstawiającym duże zwierzę:

Spring ends with Aries (ram). In my post „Ram and Bull” I explained that the ram symbol marks the end of the lambing season of the wild Eurasian sheep in Europe.

Wiosna kończy się Ariesem (baranem). W moim poście „Baran i Byk” wyjaśniłem, że symbol barana oznacza koniec okresu wylęgu jagniąt dzikich owiec euroazjatyckich w Europie.

Summer starts in Taurus (bull). In my post „Ram and Bull” I explained that the bull symbol marks the beginning of the calving season of the wild Eurasian cattle in Europe.

Lato zaczyna się w Taurusie (byk). W moim poście „Baran i Byk” wyjaśniłem, że symbol byka oznacza początek okresu wycielenia dzikiego bydła euroazjatyckiego w Europie.

Autumn starts in Leo (lion). In my post „Entemena vase” I postulated that this symbol marked the beginning of the mating season of the Eurasian lions in Europe.

Jesień zaczyna się w Leo (lwie). W swoim poście „Waza Entemena” postulowałem, że ten symbol zapoczątkował okres godowy lwów eurazjatyckich w Europie.

Winter ends in Capricorn (goat). In my post „Goat” I explained that the goat symbol marked the beginning of the mating season of the wild European Alpine ibex goat.

Zima kończy się w Capricornie (koziorożcu / kozie). W swoim poście „Koza” wyjaśniłem, że symbol kozy zapoczątkował okres godowy dzikiego koziorożca alpejskiego.

So these four animals are symbols of the four seasons

Zatem te cztery zwierzęta są symbolami czterech pór roku

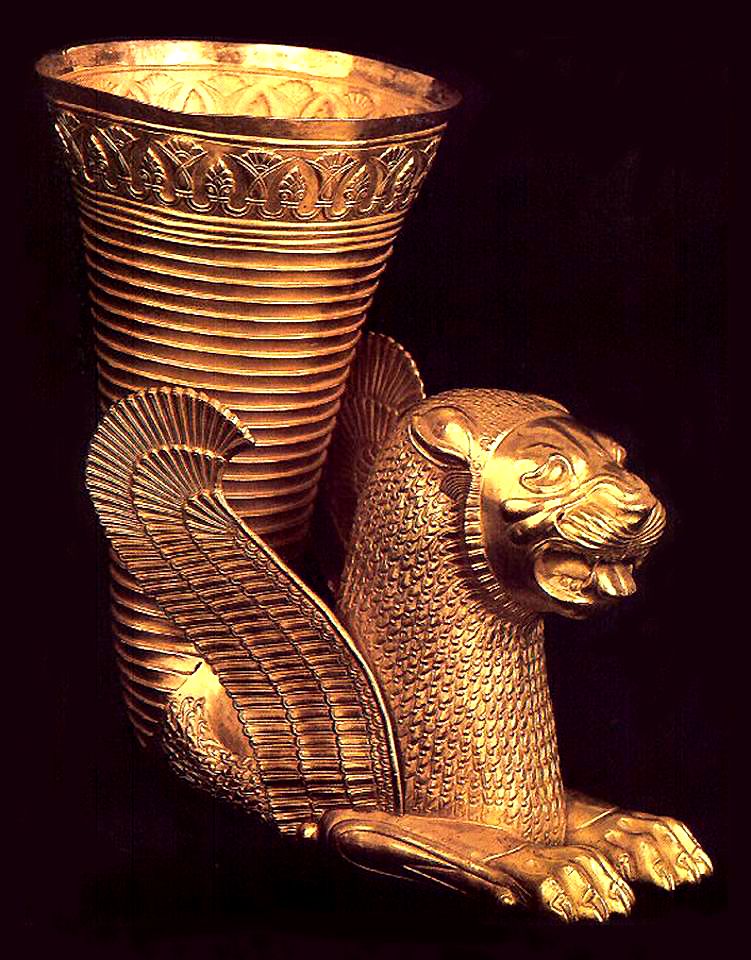

I wonder if this is the reason why the Achaemenids made their rhytons, ceremonial drinking, libation vessels, with the heads of these 4 animals?

Silver rhyton with horned ram head (Spring), Persia, Achaemenid Period, 538-331 BCE, Seattle Art Museum in Seattle, Washington.

Zastanawiam się, czy to jest powód, dla którego Achemenidzi robili swoje rytony, ceremonialne naczynia do picia, libacji, z głowami tych 4 zwierząt?

Srebrny ryton z rogatą głową barana (wiosna), Persja, okres Achemenidów, 538-331 pne, Seattle Art Museum w Seattle, Waszyngton.

Silver rhyton with bull head (Summer), Persia, Achaemenid Period, 600 – 400 BC, Cincinnati Art Museum

Srebrny ryton z głową byka (lato), Persja, okres Achemenidów, 600-400 pne, Cincinnati Art Museum

Gold rhyton with lion head (Autumn), Persia, Achaemenid Period, 500 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Złoty ryton z głową lwa (jesień), Persja, Okres Achemenidów, 500 pne, Metropolitan Museum of Art w Nowym Jorku

Silver rhyton wih goat head (Winter), Persia, Achaemenid Period, 400 – 100 BC, Met museum, New York

Srebrny ryton z głową kozła (zima), Persja, Okres Achemenidów, 400-100 pne, Muzeum Met, Nowy Jork

Now interestingly, three out of four of these animals are large wild Eurasian herbivores. There is one more large wild Eurasian herbivore, a deer. Is it possible that it somehow fits into this picture? Well it is. August, the beginning of autumn is the time when Persian fallow deer and European red deer start their mating season. Is this why we also find Achaemenids rhytons, ceremonial drinking, libation vessels with the heads of stags? Or is stag equivalent of the bull, considering that stag is linked with summer solstice and that we find „lion killing stag” scene equivalent to „lion killing bull” scene? I am not sure about this one…

Co ciekawe, trzy na cztery z tych zwierząt to duże dzikie eurazjatyckie zwierzęta roślinożerne. Jest jeszcze jeden duży dziki roślinożerca eurazjatycki, jeleń. Czy to możliwe, że jakoś pasuje do tego obrazu? No cóż, tak jest. Sierpień, początek jesieni to czas, w którym daniele perskie i jelenie europejskie rozpoczynają okres godowy. Czy dlatego znajdujemy również rytony Achemenidów, do ceremonialnego picia, naczynia libacyjne z głowami jeleni? A może jeleń jest odpowiednikiem byka, biorąc pod uwagę, że jeleń jest powiązany z letnim przesileniem i że scena „zabijania przez lwa jelenia” jest równoważna scenie „zabijającego przez lwa byka”? Nie jestem pewien co do tego …

Silver Rhyton with stag’s head, Persia, Achaemenid Period, late 400 – 300 B.C. The George Ortiz Collection

Srebrny Rhyton z głową jelenia, Persja, okres Achemenidów, późne lata 400-300 p.n.e. Kolekcja George’a Ortiza

What do you think about this?

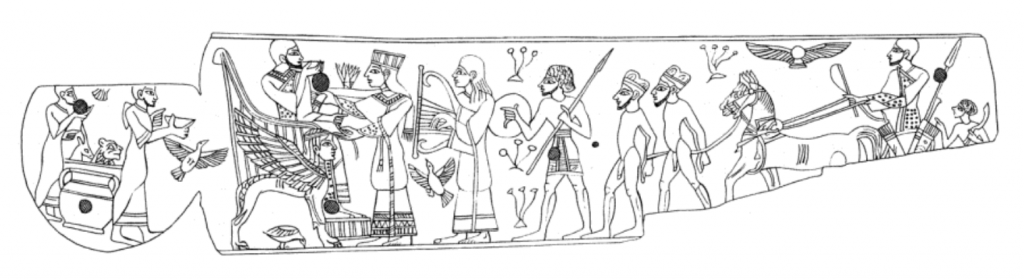

Interestingly, the same types of rhyta, with the same animal heads, were made in Levant during the second half of the second millennium BC.

This is a late Bronze Age ivory plaque from Megiddo (Israel) ca. 1200 BC. The ruler, seated on an imposing throne, drinks wine being served from a large krater behind him, using lion and goat headed horns (rhyta)

Co o tym myślisz?

Co ciekawe, te same rodzaje rytów, z takimi samymi głowami zwierząt, powstały w Lewancie w drugiej połowie drugiego tysiąclecia pne.

Jest to tablica z kości słoniowej z późnej epoki brązu z Megiddo (Izrael) ok. 1200 pne. Władca, siedzący na imponującym tronie, pije wino serwowane z dużego kratera za nim, używając rogów lwa i koziej głowy (rhyta)

„…Egyptian armies which reguralrly invaded Retenu or Canaan during LBA, made certain that they brought back animal-headed rhyta and drinking horns as tribute. Two lion-headed examples in silver are depicted on the frescoes inside the Theban tomb of Amenmose, a commander of the infantry under Tuthmosis III and his son Amenothep II. Tuthmosis III raided levant 14 times over the 54 year period of his reign. The records say that „wine flowed like water” and that „have been drunk…every day as if at feast in Egypt”. The pharaoh’s annals also record that bull-headed, ram-headed and lion-headed vessels were taken as booty. They are said to have been made in Retenu…” From „Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture” by Patrick E. McGovern

„… Egipskie armie, które regularnie najeżdżały Retenu lub Kanaan podczas LBA, z pewnością w ramach hołdu przywiozły z powrotem zwierzęce ryty i rogi do picia. Dwie srebrne głowy lwów są przedstawione na freskach wewnątrz tebańskiego grobowca Amenmose, dowódcy piechoty pod wodzą Totmesa III i jego syna Amenothepa II. Totmes III w ciągu 54 lat swojego panowania 14 razy najeżdżał Lewant. Według zapisów „wino płynęło jak woda” i „było pijane… każdego dnia jak na uczcie w Egipcie. ”. Kroniki faraona również odnotowują, że jako łup wzięto naczynia z głowami byczymi, baranimi i lwimi. Mówi się, że zostały wykonane w Retenu …„ Ze starożytnego wina: Search for the Origins of Viniculture ”autorstwa Patricka E. McGovern

źródło: Old European Culture