OEC: Gora

nadesłał Jarosław Ornicz, tłumaczenie Czesław Białczyński , autor Old European Culture

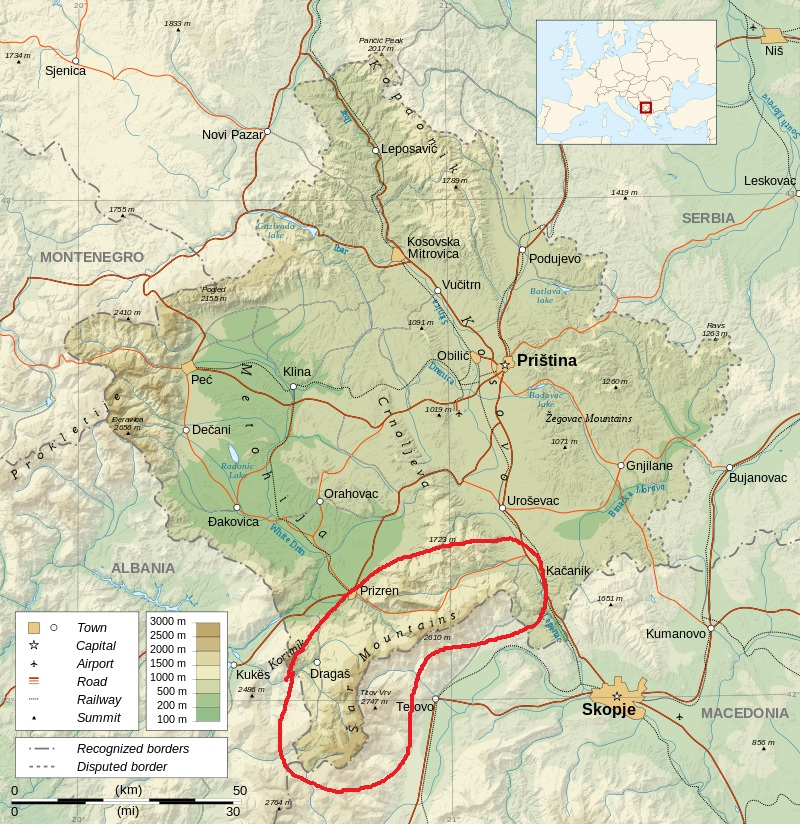

Šar Mountain mountain is a mountain range which lies on the border between Serbia (Kosovo), Makedonija and Albanija.

Góry Šar to pasmo górskie, które leży na granicy między Serbią (Kosowo), Macedonią i Albanią.

Sometimes the range is called Carska planina („Tsar’s mountain”), as a reference to the old capitals (Prizren and Skopje), courts (Nerodimlje, Pauni, Svrčin, etc.) and monasteries (Monastery of the Holy Archangels) of the Old Medieval Serbian Empire which are located in the region surrounding the mountain.

Czasami Obszar ten nazywa się Carska planina („góra cara”), jako odniesienie do starych stolic (Prizren i Skopje), posiadłości (Nerodimlje, Pauni, Svrčin itp.) i klasztorów (Klasztor Świętych Archaniołów) Starego Średniowiecznego Serbskiego Imperium, które znajduje się w regionie otaczającym te góry.

The mountain range is 85 kilometers long and has a total area of 1600 square km. It has 21 peaks which are over 2000 meter high, the highest reaching 2707 meters. This is Ljuboten peak, which is 2,498 m high.

Pasmo górskie ma 85 kilometrów długości i powierzchnię 1600 kilometrów kwadratowych. Ma 21 szczytów, które mają ponad 2000 metrów wysokości, a najwyższe osiągają 2707 metrów. Tu szczyt Ljuboten, który ma 2498 m wysokości.

Vegetation on the mountain includes crops up to around 1,000 m (3,281 ft), forests up to 1,700 m (5,577 ft), and above that lie high pastures which encompass around 550 km2 (212 sq mi). The Šar Mountain is the largest compact area covered with pastures on the European continent.

Uprawa roślin w górach obejmuje poziom do około 1000 m (3,281 ft), lasy do 1700 m (5,577 ft), a powyżej są wysokie pastwiska, które obejmują około 550 km2 (212 ²). Góra Šar to największy zwarty obszar pokryty pastwiskami na kontynencie europejskim.

Because of this the Šar Mountain highland is an ideal grazing ground for sheep. Huge flocks of sheep are brought up the mountain every spring to the highland grazing grounds, where they stay until the late autumn. Up on the mountains the sheep are minded by shepherds and their dogs, famous Šarplaninac (Šar mountain) shepherd dog.

Z tego powodu szczyty gór Szar są idealnym miejscem wypasu owiec. Ogromne stada owiec wyprowadzane są każdej wiosny na górskie pastwiska, gdzie przebywają do późnej jesieni. Na górze owce są chronione przez pasterzy i ich psy, słynne Šarplanince (Šar).

The Šarplaninac is a robust, well proportioned dog with plenty of bone, of a size that is well above the average. The coat is long and dense, with an abundant dense undercoat, making it weatherproof and suited for an outside life.

Šarplaninac jest wytrzymałym, proporcjonalnym psem o grubych kościach, znacznie powyżej średniej. Futro jest długie i gęste, z obfitym, gęstym podszerstkiem, dzięki czemu jest odporny na warunki atmosferyczne i nadaje się do życia w warunkach naturalnych górskich.

The temperament of the breed is described as independent, reliable, protective but not snappy, incorruptible and devoted to its master. The breed is aloof with outsiders, and calm until a threat to the flock presents itself. The breed has an extremely protective nature. In the absence of a flock of sheep, the Šarplaninac will often treat its humans as sheep – herding them away from danger or undesirable areas. They are serene and majestic, gentle with children and smaller dogs. They are also highly intelligent and bred to work without human supervision while guarding the flocks in the high pastures. The Šarplaninac has been known to fight or chase off wolves, lynxes and even bears.

While during the summer the upper highlands of the Šar Mountain are covered in lush green grass, during the winter they turn into a white desert covered in meters of snow.

Podczas gdy w lecie górne wyżyny góry Szar pokryte są bujną zieloną trawą, w zimie zamieniają się w białą pustynię pokrytą grubą na metry okrywą śniegu.

The official etymology of the name „Šar Mountain” says that it comes from the Old Slavic word „šar” meaning pattern. The explanation is that the mountain looks patterned due to its layers of different vegetation. On this picture of the Šar Mountain you can clearly see the white layer of snow covered highlands over the black layer of forests.

Oficjalna etymologia nazwy „góra Szar” głosi, że pochodzi ona od starosłowiańskiego słowa „šar” oznaczającego wzór. Wyjaśnienie jest takie, że góra wygląda na wzorzystą ze względu na warstwy innej roślinności. Na tym zdjęciu góry Šar można wyraźnie zobaczyć białą warstwę ośnieżonych wyżyn na czarnej warstwie lasów.

This is indeed a good etymology. But there is another possible etymology.

To jest naprawdę dobra etymologia. Ale jest jeszcze inna możliwa etymologia.

In Antiquity, the Šar Mountain was known as Scardus, Scodrus, or Scordus (το Σκάρδον ὂρος in Polybius and Ptolemy) mountain; This name means the mountain of Scordisci. The same Celtic Scordisci who ruled what is today Serbian part of the Balkans for centuries, and whose capital was Singidun, today’s Serbian capital Belgrade. The same Scordisci who, I believe, still live in Serbian genes, culture and language.

W starożytności góra Szar znana była jako góra Scardus, Scodrus lub Scordus (το Σκάρδον ὂρος w Polybius i Ptolemeusz); Ta nazwa oznacza górę Scordisci. Ci sami celtyccy Scordisci [Szkodrowie/Skordyskowie. CB], którzy rządzili przez wieki serbską częścią Bałkanów, a których stolicą był Singidun, dzisiejsza serbska stolica, Belgrad. Ci sami Scordisci, którzy, jak sądzę, nadal żyją w serbskich genach, kulturze i języku.

It is said that their tribal name may be connected to the Scordus, the Šar mountain. Are Scordisci the people from Scordus, or is Scordus the mountain of Scordisci? This is not really that important. But what is important is that if Celtic Scordisci lived on Scordus Mountain, then they would have given the mountain a Celtic name.

Mówi się, że ich nazwa plemienna może być połączona ze Scordusem, górą Šar. Czy Scordisci to ludzie z Scordus, czy też Scordus to góra Scordisci (Skordysków)? To naprawdę nie jest tak ważne. Ważne jest jednak to, że gdyby Celtowie Scordisci żyli na górze Skordus, to nadaliby jej nazwę celtycką.

The mountain was known to the Greeks as Scordus Mountain, the mountain of Scordisci, but what did Scordisci call their mountain? Is it possible that they they called it Šar mountain?

Góra była znana Grekom jako Góra Scordus, góra Scordisci, ale jak sami Scordisci (Szkodrowie) nazywali swoją górę? Czy to możliwe, że nazywali ją Szarą Górą?

And this is why I believe that this could be so:

If you look at the above panoramic picture of the Šar Mountain, you will see that it dwarfs the surrounding lowlands. It is a great, big, high mountain. It is also as I already said, the biggest and one of the best highland pastures in Europe. So if the Celts called this mountain anything, they must have called it something like high, big, great…

Jeśli spojrzysz na powyższe panoramiczne zdjęcie góry Szar, zobaczysz, że krasnoludy otaczają niziny. Jest to wielka, wielka góra. Jest to także, jak już powiedziałem, największe i jedno z najlepszych górskich pastwisk w Europie. Więc jeśli Celtowie nazywali tę górę jakkolwiek, musieli ją nazwać czymś wysokim, wielkim, olbrzymim…

I already said in many of my posts that Scordisci must have spoken some variant of Gaelic, because there are so many common words in Gaelic and Serbian. So is there a Gaelic word which sounds like „Šar” and which means something like high, big, great? Yes there is.

W wielu moich wypowiedziach powiedziałem już, że Scordisci musieli mówić jakąś odmianą gaelickiego, ponieważ w języku gaelickim i serbskim jest wiele podobnych popularnych słów. Czy jest jakieś gaelickie słowo, które brzmi jak „Szar”, a które oznacza coś wysokiego, wielkiego, olbrzymiego? Tak jest.

In Gaelic there is a word „sáir”, „sár”, which is used as augmentative prefix meaning very, exceeding, excessive, great, most, excellent, the one above all… This word is found in both Old Irish and Early Irish.

W języku gaelickim występuje słowo „sáir”, „sár”, które jest używane jako prefiks augmentatywny oznaczający bardzo, przekraczający, nadmierny, wielki, najbardziej, doskonały, ten przede wszystkim … Słowo to można znaleźć zarówno w języku staroirlandzkim, jak i wczesnoirlandzkim.

For instance the Irish word „mhaith” means good, goodness. With prefix „sár” it becomes „sármhaith” (pronounced „sarwai”, „sorwa” depending on the dialect) which means Excellent (most, very good).

Na przykład irlandzkie słowo „mhaith” oznacza dobro, dobroć. Z prefiksem „sár” staje się „sármhaith” (wymawiane „sarwai”, „sorwa” w zależności od dialektu), co oznacza Excellent (najlepsze, bardzo dobre).

[CB – Zwracam tutaj uwagę na ten zapis Irlandzki, który ma mieć korzenie celtyckie, ale tak naprawdę moim zdaniem ma korzenie po prostu słowiańskie, słowiano-aryjskie i jest identyczny z nazwą Sarmaci:„sármhaith”. Należy tę zbieżność zderzyć z inną zbieżnością gdyż Ireland podobnie jak Iran – Aria-land (Adam Wojtanek: „Arjowie nazywali siebie „Arja”. Tak również nazywali siebie starożytni Persowie. Nazwa ta przetrwała w nazwie Iran (wymawia się „Ajran”); z tego samego źródłosłowu wywodzi się też Eire (Ireland – wymawia się „Ajrland” co znaczy „Ziemia Arów”) dawna nazwa Irlandii – nazwa najdalej na zachód położonego kraju, do jakiego dotarli Indoeuropejczycy w czasach starożytnych.”)]

Here is a list of Irish constructs which use sáir- (sár-). I will here just list few most interesting ones:

Oto lista irlandzkich konstrukcji, które używają sáir- (sár-). Tutaj wymienię tylko kilka najciekawszych:

sáire, excess, excellence.

sáir-bheannach, having lofty peaks or mountains.

sáir-bhinneálta, a., exquisitely handsome.

sáir-bhrígh, great strength.

sáir-bhríoghach, very powerful, very substantial.

sár-aibéil, very quick, extremely fast.

sár-chaoin, very gentle.

sár-mhaith, excellent, surpassing good.

sár-oilte, well-educated skilful.

…

Here you can hear how the word sáir- (sár-) is pronounced in three different Irish dialects. It is currently pronounces as „sar”, „ser”, „saor” and „sor”. It is quite possible that the word was once also pronounced as „Shar” or „Šar”.

Tutaj słychać, jak słowo sáir- (sár-) wymawia się w trzech różnych irlandzkich dialektach. Obecnie jest określane jako „sar”, „ser”, „saor” i „sor”. Jest całkiem możliwe, że słowo to było kiedyś również wymawiane jako „Shar” lub „Šar”.

Sár Mountain would then mean Great, High Mountain. Or Great Highlands, Excellent, Superior, The best highland pasture…Which is exact description of the Šar Mountain, the bigest and the best highland pasture in Europe.

Góra Sár oznaczałaby wtedy Wielką, Wysoką Górę. Lub Great Highlands, Excellent, Superior, Najlepsze pastwiska góralskie … To jest dokładny opis góry Šar, największego i najlepszego pastwiska górskiego w Europie.

Well this is just a possibility…

Cóż, to jest tylko możliwość…

The south western slopes of the Šar Mountain are known as Gora. I believe that this name could have once been applied to the whole mountain, as Gora in Serbian simply means mountain or forest or forested mountain, or highland. This fits perfectly with the meaning of the potential Gaelic name for the mountain Sár (Great, High, Excelent) mountain. People who live in this region call themselves Gorani, Goranci which literally means mountain people, highlanders or Našinci, which literally means „our people, our ones”.

Południowo-zachodnie stoki góry Szar znane są jako Gora. Wierzę, że ta nazwa mogła kiedyś zostać zastosowana do całej góry, ponieważ Gora w języku serbskim oznacza po prostu góry, zalesione góry lub górę. To idealnie pasuje do znaczenia potencjalnej gaelickiej nazwy góry Sár (Wielka, Wysoka, Doskonała). Ludzie mieszkający w tym regionie nazywają się Gorani, Goranci, co dosłownie oznacza ludzi gór, górali lub Našinci, co dosłownie oznacza „nasz lud, nasi”.

[CB – Znów się wtrącę, gdyż chcę zwrócić uwagę na związek Gorani, Goranci i Naszinci – z identycznym kompleksem nazw polskich Górale i Har-Nasie Gora-Nasi, Har-Nasi, a wszystko to nawiązuje wprost do nazwy Karpat – Harpąt i Harii, czyli Hariów znanych później jako Ariowie. Nawiązuje też do nas Nasyci/Nesyci i Nasemile o czym w kolejnym artykule]

Goranci are Muslim Slavic people who today consider themselves to be a separate ethnic group.

However, the Ottoman census from 1591 (TKGM, TD № 55 (412), Defter sandžaka Prizren iz 1591. godine) says that Šar Mountain was inhabited exclusively by Serbs, so it is possible that they were originally Serbs who later converted to Islam and eventually developed their own new identity.

Goranci są muzułmańskimi Słowianami, którzy dziś uważają się za odrębną grupę etniczną.

Jednak spis ludności z 1591 r. (TKGM, TD № 55 (412), Defter sandžaka Prizren iz 1591. godine) mówi, że Szar był zamieszkany wyłącznie przez Serbów, więc możliwe, że byli oni pierwotnie Serbami, którzy później nawrócili się na islam i w końcu zyskali nową własną tożsamość.

It is important to know that the Islamisation of the Gorani people only happened in the 18th and 19th century. The Ottoman abolition of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid and Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in 1766/1767 is thought to have prompted the Islamization of Gora as was the trend of many Balkan communities. The last Christian Gorani, Božana (God given in Serbian), died in the 19th century…

Ważne jest, aby wiedzieć, że islamizacja ludu Gorani miała miejsce tylko w XVIII i XIX wieku. Oskarżycielskie zniesienie bułgarskiego arcybiskupstwa w Ochrydzie i serbskiego patriarchatu Peća w latach 1766-1767 spowodowało islamizację Gory, podobny był trend wielu społeczności bałkańskich. Ostatni chrześcijanin Gorani, Božana (Bóg dany w języku serbskim), zmarł w XIX wieku …

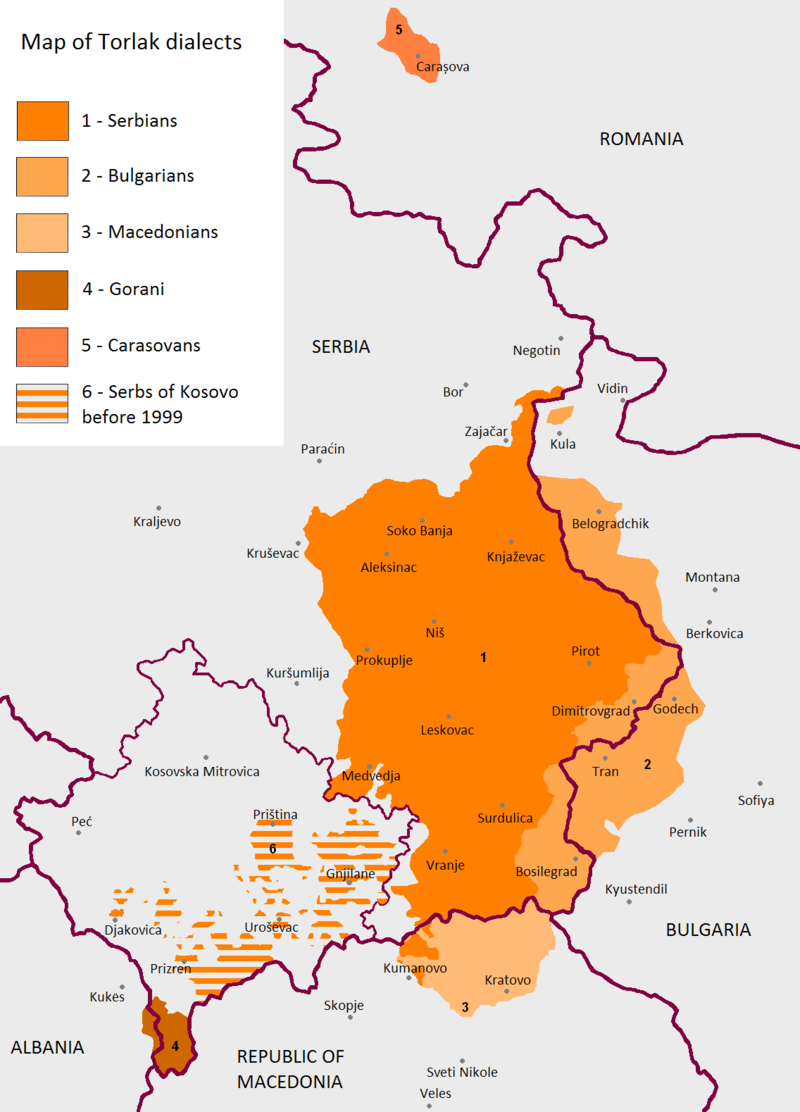

That Gorani are Islamised Serbs or at least closely related to Serbs can be seen from their language, which they call Našinski, which literally means „our language”. This is a dialect of Serbian which is part of the Torlakian dialect group which is officially called „the transitional dialect between Eastern and Western South Slavic languages” but I believe is the root dialect from which both Eastern and Western South Slavic languages evolved. The Gorani speech is also classified as an Old-Shtokavian dialect of Serbian (Old Medieval Serbian). You can see from this map showing the distribution of the Torlakian dialects, that they are mostly spoken by Serbs in Serbia. The areas in Northern Makedonija, Western Bulgaria and Kosovo (including the Šar Mountain), are all regions where either there still is, or until recently was a large Serbian population:

To, że Gorani są zislamizowanymi Serbami lub przynajmniej blisko spokrewnieni z Serbami, widać z ich języka, który oni nazywają Našinski, co dosłownie oznacza „nasz język”. Jest to dialekt języka serbskiego, który jest częścią grupy dialektów Torłakowskich, która oficjalnie nazywa się „dialektem przejściowym między wschodnimi i zachodnimi słowiańskimi językami”, ale uważam, że jest to główny dialekt, z którego wyewoluowały języki wschodniego i zachodniego południowosłowiańskiego. Mowa Gorańska jest również klasyfikowana jako staroświecki dialekt serbski (staro-średniowieczny serbski). Na tej mapie można zobaczyć rozmieszczenie dialektów torłakowskich, które są w większości używane przez Serbów w Serbii. Obszary w północnej Macedonii, zachodniej Bułgarii i Kosowie (łącznie z Górą Szarą) to wszystkie regiony, w których dawniej istniała, lub do niedawna, duża populacja Serbów:

As you can see from the below map, based on the census from the 2011, today the Šar Mountain is, except for the urbanised low lying valley around Prizren which is mostly populated by Albanians, still an island of Slavic culture and language in Albanian dominated Kosovo. Three Slavic ethnic groups now live on the mountain. Orthodox Christian Slavic population which declares themselves a Serbs and two groups of Muslim Slavic population which declare themselves as either Bosniaks or Goran, where these „Bosniaks” are Goran people who have recently been converted to „Bosniaks”…

Jak widać z poniższej mapy, opartej na spisie z 2011 roku, dziś góra Szar jest, z wyjątkiem zurbanizowanej, nisko położonej doliny wokół Prizren, która jest w większości zaludniona przez Albańczyków, nadal wyspą słowiańskiej kultury i języka w zdominowanym przez Albańczyków Kosowie. Obecnie na górze żyją trzy słowiańskie grupy etniczne. Ortodoksyjno-chrześcijańska ludność słowiańska, która uważa się za Serbów i dwie grupy muzułmańskiej ludności słowiańskiej, która uważa się albo za Bośniaków, albo Gorani, gdzie ci „Bośniacy” to też lud Goran, który niedawno stał się „Bośniakami” …

Regardless of what the people from Šar Mountain call themselves, Serbs, Gorani, Bosniaks, Slavic population of Šar Mountain is at the moment under huge economic, political and cultural pressure. More and more people are leaving as they see no future for themselves in Albanian dominated Kosovo where they are treated as undesirable. They feel abandoned by everyone, left to themselves and their destiny. The mountain of Scordisci might soon be empty…

Bez względu na to, za kogo ludzie z Gór Šar się uważają, czy za Serbów, Gorani, Bośniaków, słowiańska ludność Szarskiej Góry jest obecnie pod ogromną presją ekonomiczną, polityczną i kulturalną. Coraz więcej osób odchodzi stąd, ponieważ nie widzą przyszłości dla siebie w Albanii zdominowanej przez Kosowo, gdzie traktuje się ich jako niepożądanych. Czują się opuszczeni przez wszystkich, pozostawieni samym sobie i swojemu przeznaczeniu. Góra Scordisci może wkrótce zostać opuszczona …

This is a poem written by Sadik Idrizi Aljabak (1954), a Goran poet. The poem is written in Goran dialect and it describes perfectly the struggle of any ethnic group anywhere which is trying to survive religious, political and economic oppression and preserve its culture and languge….I tried to translate it into English as best as I could, but my Gorani is not the best 🙂

Jest to wiersz napisany przez Sadika Idrizi Aljabaka (1954), poetę Gorana. Wiersz pisany jest dialektem Goran i doskonale opisuje walkę którejkolwiek z tych grup etnicznych, która próbuje przetrwać religijny, polityczny i ekonomiczny ucisk oraz zachować swoją kulturę i język … Próbowałem przetłumaczyć go na język angielski tak dobrze jak mogłem, ale mój Gorani nie jest najlepszy 🙂

AZIL

ako idete svi

(a viđim ste trnalje)

koj će zborne jezik naš

dukat istenčen

ot babovci začuvan

vo godine mlogo poteške

ako izbegate svi

dženazina koj će isprati

du grobišta parosane

koj će dava ime cvećinam

vo ljivade pokraj reka

svi ako idete

(ka što ste rnalje)

sokaci će se zagajljujet

kuće prazne će ostanet

pesne naše za nikogo

If you all leave

(and I can see you are getting ready)

who is going to speak our language

the golden coin given to us by our forefathers to take care of

but which was thinned during many difficult years

If you all run away

who is going to carry the dead to the cemeteries

cemeteries which are already overgrown and unkempt

who is going to give names to the flowers

which grow in the meadows along the rivers

If you all leave

(and I can see you are getting ready)

the streets of our villages will become quiet

our houses will stay empty

and there will be no one left to sing our songs…

Jeśli wszyscy odejdą

(a widzę, że się szykujesz)

kto będzie mówił w naszym języku

co jako ten dukat istnieje

przez babki nasze zachowany

przez wiele trudnych lat

Jeśli wszyscy uciekną

kto będzie nieść zmarłych na cmentarze

cmentarze, które są już zarośnięte i zaniedbane

kto ma nadawać nazwy kwiatom

które rosną na łąkach wzdłuż rzek

Jeśli wszyscy odejdą

(a widzę, że się szykujesz)

ulice naszych wiosek ucichną

nasze domy pozostaną puste

i nie będzie już nikogo,

kto mógłby śpiewać nasze piosenki …

I know some people are going to say: there is no way that the present Serbian (and Gorani) people who live on the Mountain of Scordisci have anything to do with the Celtic Scordisci. Scordisci lived in Serbia in the 4th and 3rd century BC and Serbs only arrived to Serbia (and Gora) in the 7th century AD. These two people are in no way connected.

Wiem, że niektórzy ludzie będą mówić: nie ma możliwości, że obecni Serbowie (i Gorani), którzy mieszkają na górze Skodrysków nie mają nic wspólnego z celtyckimi Skodrysami. Skordyskowie mieszkali w Serbii w 4. i 3. wieku p.n.e., a Serbowie przybyli do Serbii i (i w Gora) w 7 wieku naszej ery. Te dwie nacje nie są w żaden sposób połączone.

The people who say things like this still believe in now completely destroyed population replacement theory, which states that as new people moved into the Balkans, they exterminated and replaced the old population that they found there. Hence Romans replaced Celts, Goths replaced Romans, Slavs replaced Goths…

Ludzie, którzy mówią takie rzeczy nadal wierzą w teraz całkowicie nieaktualne teorie o zastępowalności ludności, które stanowią, że nowi ludzie przeniósłszy się na Bałkany wytępili i zastąpili starą populację, jaką tam zastali. Dlatego też Rzymianie zastąpili Celtów, Goci zastąpili Rzymian, Słowianie zastąpili Gotów …

Genetic analysis of the current Balkan population shows that actually newcomers just merged into the existing population. Today Balkan population is one of the most genetically diverse populations in the world. Basically anyone who ever lived in the Balkans have left its genetic mark on the current population, which in Serbia (and Gora) today calls themselves Serbs (and Gorani).

Analiza genetyczna obecnej populacji bałkańskiej pokazuje, że de facto nowo przybyli połączyli się z istniejącą populacją. Dzisiaj populacja bałkańska jest jedną z najbardziej zróżnicowanych genetycznie populacji na świecie. W zasadzie każdy, kto kiedykolwiek żył na Bałkanach zostawił swój ślad genetyczny w obecnej populacji, która w Serbii (i Gorze) nazywa się dzisiaj Serbami (i Gorani).

Genetic data just confirms what archaeological, ethnographic and linguistic data have been hinting to already: that today’s Serbs (and Gorani) are the genetic, cultural and linguistic amalgam of all the previous people who lived in the Balkans, probably since Mesolithic…

Dane genetyczne tylko potwierdzają to, co dane archeologiczne, etnograficzne i językowe sugerowały już wcześniej: że dzisiejsi Serbowie (i Gorani) są genetycznie, kulturowo i językowo amalgamatem wszystkich poprzednich ludzi żyjących na Bałkanach, prawdopodobnie od mezolitu …

Now have a look at this:

Teraz spójrz na to:

In Kosovo, there are 21 Gorani-inhabited villages: Baćka, Brod, Vranište, Globočica, Gornja Rapča, Gornji Krstac, Dikance, Donja Rapča, Donje Ljubinje, Gornje Ljubinje, Donji Krstac, Dragaš, Zli Potok, Kruševo, Kukuljane, Lještane, Ljubošte, Mlike, Orčuša, Radeša and Restelica.

In Albania, there are 10 Gorani-inhabited villages: Zapod, Pakisht, Orçikël, Kosharisht, Cernalevë, Orgjost, Orshekë, Borje, Novosej and Shishtavec.

W Albanii jest 10 zasiedlonych przez Gorani miejscowości: Zapod, Pakisht, Orçikël, Kosharisht, Cernalevë, Orgjost, Orshekë, Borje, Novosej i Shishtavec.

In the Republic of Macedonia, there are 2 Goranci-inhabited villages: Jelovjane and Urvič.

W Macedonii są 2 Gorańskie miejscowości: Jelovjane i Urvič.

In several of the Gorani villages in Kosovo, Donje Ljubinje, Gornje Ljubinje, brides paint their faces in stunning patterns and embellish them with sequins for their wedding day.

W kilku wsiach Gorani w Kosowie, Donje Ljubinje, Gornje Ljubinje, narzeczone malują twarze i na nich wspaniałe wzory oraz zdobią je cekinami na ślub.

It is said that the three golden circles drawn on the bride’s face represent the three phases of life, which are bound to each other with golden paths, while the red ones represents fertility and the remaining blue spots represent a happy and healthy family.

The makeup is also said to ward off bad luck and has been a part of the wedding celebration since the time immemorial. This unusual custom has attracted the attention of local and foreign ethnologists.

Mówi się też, że makijaż odstraszał „złe” (chronił od pecha) i był częścią uroczystości weselnych od niepamiętnych czasów. Ten niezwykły zwyczaj przyciągnął uwagę lokalnych i zagranicznych etnologów.

The same wedding custom is only found in the remote village of Draginovo, Bulgaria, inhabited by Slavic Muslim minority called Pomaks. The face painting ritual is in Bulgaria called gelina, and is performed to mark girls transition into married life.

Ten sam zwyczaj weselny znajduje się w odległej wiosce Draginovo w Bułgarii, zamieszkanej przez słowiańską mniejszość muzułmańską zwaną Pomakami. Rytuał malowania twarzy jest w Bułgarii zwany gelina i jest wykonywany, aby oznaczyć przejście dziewcząt w życie małżeńskie.

During the gelina, Pomak brides are painted over with a thick cosmetic creme mask called „belilo” (whitening).

Podczas geliny [ Żaliny – żalów weselnych CB] narzeczone u Pomaków są malowane grubą kosmetyczną maską kremową zwaną wybielaniem.

Dekoracje twarzy zawsze zawierają trzy koła, po jednym na każdym policzku i jedno na podbródku.

The face is then painted with elaborate floral patterns and further decorated with sequins.

Po otrzymaniu błogosławieństwa ślubnego, panna młoda jest eskortowana przez członków jej rodziny z domu dzieciństwa i do domu pana młodego, gdzie jej mąż zdejmuje makijaż.

This elaborate tradition is on the verge of extinction.Now this is 13th century BC Mycenaean plaster head, currently in National Archaeological Museum Athens.

Ta skomplikowana tradycja jest na skraju wyginięcia. Poniżej to głowa mykeńska z XIII wieku przed Chrystusem, obecnie w Narodowym Muzeum Archeologicznym w Atenach.

Mycenaean civilisation was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1600–1100 BC. It is the period into which the Trojan war is now placed by the Archaeologists.

Cywilizacja mykeńska była ostatnią fazą epoki brązu w starożytnej Grecji, obejmującą okres od około 1600-1100 pne. Jest to okres, w którym Wojna Trojańska jest obecnie umieszczana przez Archeologów.

This is the recreation of Helen of Troy’s maquillage based on the above plaster head.

To jest rekonstrukcja makijażu ślubnego Heleny Trojańskiej wykonana w oparciu o powyższą gipsową głowę.