Acorns in archaeology

© by Goran Pavlovic © tłumaczenie by Czesław Białczyński

In my last post I talked about Oaks and how useful they were and are to people. The last thing that I said in my last post is that acorns had been eaten by humans since at least late Paleolithic times right up to modern times, and that I would write about acorns and acorn eaters in my next few posts. In this post I will write about archaeological evidence we have for human consumption of acorns during the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Copper age, Bronze age and Iron age. I hope you find the data presented in this post as eye opening as I did find it, and that you will start seeing acorns in a completely different light from now on.

W moim ostatnim poście mówiłem o Dębach i o tym, jak przydatne były i są dla ludzi. Ostatnią rzeczą, którą powiedziałem w moim ostatnim poście, jest to, że żołędzie były zjadane przez ludzi od co najmniej późnego paleolitu aż do czasów współczesnych, i że napiszę o żołędziach i zjadaczach żołędzi w kilku następnych postach. W tym poście napiszę o dowodach archeologicznych, które mamy na temat spożywania żołędzi przez ludzi w okresie paleolitu, mezolitu, neolitu, epoki miedzi, epoki brązu i epoki żelaza. Mam nadzieję, że dane przedstawione w tym poście uznasz za otwierające oczy, tak jak ja je znalazłem, i że od teraz zaczniesz widzieć żołędzie w zupełnie innym świetle.

Acorns are usually eaten roasted, and during roasting the thin-walled shells are carbonised and destroyed, which makes the macro particle acorn detection in the archaeological remains very difficult. On dry sites wind would then disperse the acorn ash and make it even more difficult to detect. On wet sites we have another problem and that is that like for most other starch rich seeds, the preservation of acorns in waterlogged conditions is not very good. Acorns only preserve well once charred because the elemental carbon of charcoal is not attacked by chemical or biological processes in sediments. But as I said already, when they are fragmented during or after charring, it can be hard to identify them as the bits get scattered. In Eastern North America where archaeobotanical finds of acorns are abundant, the majority of finds consist of fragments of acorn shell of 2mm or less. This might indicate that in Europe most of the evidence of acorn use may have been overlooked or was not preserved. Because of the absence of macro remains we have to rely on micro remains and they are not easy to detect. To detect micro remains of food plants you need to use flotation technique and microscope analysis. At the submerged Mesolithic site of Tybrind Vig in Denmark which is known for its excellent preservation conditions, acorn use has only been attested by the identification of small fragments of acorn using a scanning electron microscope. The same happened at the sites of Cova Fosca and Roc de Migdia in Spain, which had no previous evidence of acorns, and where the presence of acorn parenchyma was attested only by using a scanning electron microscope. However both these techniques are expensive and require well equipped archaeobotanical laboratories. Because of this there are significant national and regional differences in the intensity of archaeobotanical research, resulting in acorn traces being missed among the archaeological material and in an underestimation of the use of acorns as a source of human nutrition in the past.

Żołędzie są zwykle spożywane pieczone, a podczas pieczenia cienkościenne muszle ulegają zwęgleniu i zniszczeniu, co bardzo utrudnia wykrywanie makrocząsteczek żołędzi w pozostałościach archeologicznych. W suchych miejscach wiatr rozproszyłby wtedy popiół z żołędzi i jeszcze bardziej utrudniłby jego wykrycie. Na mokrych stanowiskach mamy inny problem, a mianowicie, podobnie jak w przypadku większości innych nasion bogatych w skrobię, konserwacja żołędzi w warunkach podmokłych nie jest zbyt dobra. Żołędzie zachowują się dobrze tylko po zwęgleniu, ponieważ pierwiastkowy węgiel węgla drzewnego nie jest atakowany przez procesy chemiczne lub biologiczne w osadach. Ale jak już powiedziałem, kiedy są rozdrobnione podczas lub po zwęgleniu, może być trudno je zidentyfikować, ponieważ cząstki są rozproszone. We wschodniej Ameryce Północnej, gdzie znaleziska archeobotaniczne żołędzi są obfite, większość znalezisk składa się z fragmentów skorupy żołędzi o wielkości 2 mm lub mniejszej. Może to wskazywać, że w Europie większość dowodów używania żołędzi mogła zostać przeoczona lub nie została zachowana. Ze względu na brak makropozostałości musimy polegać na mikropozostałościach, które nie są łatwe do wykrycia. Do wykrywania mikropozostałości roślin jadalnych należy zastosować technikę flotacji oraz analizę mikroskopową. W zatopionym mezolitycznym stanowisku Tybrind Vig w Danii, które słynie z doskonałych warunków zachowania, użycie żołędzi zostało potwierdzone jedynie poprzez identyfikację małych fragmentów żołędzi za pomocą skaningowego mikroskopu elektronowego. To samo stało się na stanowiskach Cova Fosca i Roc de Migdia w Hiszpanii, gdzie wcześniej nie było żadnych śladów żołędzi, a obecność miąższu żołędzi potwierdzono jedynie za pomocą skaningowego mikroskopu elektronowego. Jednak obie te techniki są drogie i wymagają dobrze wyposażonych laboratoriów archeobotanicznych. Z tego powodu istnieją znaczne krajowe i regionalne różnice w intensywności badań archeobotanicznych, co skutkuje pomijaniem śladów żołędzi w materiale archeologicznym i niedocenianiem wykorzystania żołędzi jako źródła pożywienia człowieka w przeszłości.

This is the main reason why hazelnuts are usually the most frequently found collected plants on archaeological sites. Hazelnut are eaten raw, where the husk is broken and discarded so we have a chance to find big fragments close together. Also hazelnut husks are far more durable than acorn ones. Another reason why acorns are not detected in larger quantities on archaeological sites is because a lot of the acorn processing is usually undertaken completely or partially off site in the actual oak groves, on river edges, collective grinding stone…. which all adds to the difficulty of detecting acorns among the food remains.

Jest to główny powód, dla którego orzechy laskowe są zwykle najczęściej spotykanymi roślinami zebranymi na stanowiskach archeologicznych. Orzechy laskowe są spożywane na surowo, gdzie łuska jest łamana i odrzucana, dzięki czemu mamy szansę znaleźć duże fragmenty blisko siebie. Również łupiny orzechów laskowych są znacznie trwalsze niż żołędzie. Innym powodem, dla którego żołędzie nie są wykrywane w większych ilościach na stanowiskach archeologicznych, jest to, że większość przetwarzania żołędzi jest zwykle prowadzona całkowicie lub częściowo poza terenem rzeczywistych gajów dębowych, na brzegach rzek, zbiorczym kamieniu szlifierskim…. trudność w wykryciu żołędzi wśród resztek jedzenia.

Even with all these difficulties in detecting acorns, there is enough archaeological evidence that shows that acorns were much more important food source than most people, including most archaeologists think. The number of acorn finds on archaeological sites is still high. At several Mesolithic sites in Europe, acorns are only outnumbered by hazelnuts, the husks of which are far more durable. Acorns are the most frequently found wild fruits at protohistoric archaeological sites in France. In Spain, acorns are third (after wheat and barley) in terms of frequency of occurrence among archaeobotanical remains, thus even more frequent than legumes such as peas and lentils.

Nawet przy tych wszystkich trudnościach w wykrywaniu żołędzi istnieje wystarczająco dużo dowodów archeologicznych, które pokazują, że żołędzie były znacznie ważniejszym źródłem pożywienia, niż myśli większość ludzi, w tym większość archeologów. Liczba znalezisk żołędzi na stanowiskach archeologicznych jest wciąż wysoka. W kilku mezolitycznych miejscach w Europie żołędzie przewyższają liczebnie jedynie orzechy laskowe, których łupiny są znacznie trwalsze. Żołędzie to najczęściej spotykane dzikie owoce na protohistorycznych stanowiskach archeologicznych we Francji. W Hiszpanii żołędzie zajmują trzecie miejsce (po pszenicy i jęczmieniu) pod względem częstości występowania wśród szczątków archeobotanicznych, a więc nawet częściej niż rośliny strączkowe, takie jak groch i soczewica.

The fact that acorns are no longer considered as being edible is also making it likely that archaeologists would not even look for them when they are looking for human food traces. Also when found on archaeological sites acorns are likely to be misunderstood and misinterpreted as accidental blow in or as animal food. But ethnographic and historical evidence is telling us that in some parts of the world acorns were used as human food until very recently.

Fakt, że żołędzie nie są już uważane za jadalne, sprawia również, że archeolodzy nawet nie będą ich szukać, gdy szukają śladów ludzkiego jedzenia. Również znalezione na stanowiskach archeologicznych żołędzie mogą zostać źle zrozumiane i błędnie zinterpretowane jako przypadkowe zdarzenie lub jako pokarm dla zwierząt. Ale dowody etnograficzne i historyczne mówią nam, że w niektórych częściach świata żołędzie były używane jako pokarm dla ludzi aż do niedawna.

During the pre-agricultural period acorns were an important plant food resource for hunter-gatherers in Europe. Archaeological evidence supports the conclusion that acorns have always been an attractive food resource within various resource strategies, including agrarian societies. In prehistoric agricultural communities, acorns may have played a role as food substitute or reserve for bad times, reserved for emergencies, for example when cereal agriculture had failed.

W okresie przedrolniczym żołędzie były ważnym źródłem pożywienia roślinnego dla łowców-zbieraczy w Europie. Dowody archeologiczne potwierdzają wniosek, że żołędzie zawsze były atrakcyjnym źródłem pożywienia w ramach różnych strategii dotyczących zasobów, w tym w społeczeństwach agrarnych. W prehistorycznych społecznościach rolniczych żołędzie mogły odgrywać rolę substytutu żywności lub rezerwy na złe czasy, zarezerwowanej na sytuacje kryzysowe, na przykład gdy uprawa zbóż zawiodła.

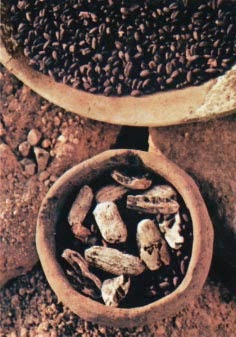

Within the context of agricultural sites acorns are usually located close to fireplaces and in furnaces. Frequently they are accompanied by other crops. In addition, acorns are common finds in vessels and storage pits. They are often shelled and mixed with cereals. Acorns also occur in shallow pits and are also found unshelled. Acorns are found in graves, and their appearance there as sacrificial offering cannot be discounted.

W ramach kontekstu agrikulturowego miejsca żołędziowe są zwykle zlokalizowane w pobliżu palenisk i pieców. Często towarzyszą im inne uprawy. Ponadto żołędzie są częstym znaleziskiem w naczyniach i dołach magazynowych. Często są łuskane i mieszane ze zbożami. Żołędzie występują również w płytkich dołach, a także znajdują się w stanie niełuskanym. Żołędzie znajdują się w grobach, a ich pojawienie się tam jako ofiara jest nie do przecenienia.

The high number of prehistoric sites across oak growing regions of the Northern Hemisphere where acorns have been found and the large number of acorns recovered from some of these sites are confirming that acorns have been one of the most important food sources for humans in the oak growing regions of the Northern Hemisphere since Paleolithic times.

Duża liczba prehistorycznych miejsc w regionach uprawy dębu na półkuli północnej, w których znaleziono żołędzie, oraz duża liczba żołędzi odzyskanych z niektórych z tych miejsc potwierdzają, że żołędzie były jednym z najważniejszych źródeł pożywienia dla ludzi w obszarach wystęowania dębu w regionach półkuli północnej od czasów paleolitu.

I will here present the list of all the cultures on whose sites acorns were found among food remains. The list is far from being definitive, and I would appreciate any information about sites that I have missed. But as far as I know this is the most comprehensive list of acorn finds in archaeological material freely available in English on the Internet. And the list reads like „who’s who” of the Northern Hemisphere ancient history, containing all the most advanced and important cultures of the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Copper age, Bronze age and Iron age. I believe that as the archaeobotanical research intensifies, we will see more and more evidence of the use of acorns as food. But I believe that even this much is enough to prove the point. All the references to the original documents containing data about acorns in archaeological sites are listed at the end of the post with clickable links.

Przedstawię tutaj listę wszystkich kultur, na których stanowiskach znaleziono żołędzie wśród resztek jedzenia. Lista nie jest ostateczna i byłbym wdzięczny za wszelkie informacje o wzmiankach, które przegapiłem. Ale o ile mi wiadomo, jest to najbardziej wyczerpująca lista znalezisk żołędzi w materiale archeologicznym, swobodnie dostępnym w języku angielskim w Internecie. A lista brzmi jak „kto jest kim” w starożytnej historii półkuli północnej, zawierającej wszystkie najbardziej zaawansowane i ważne kultury paleolitu, mezolitu, neolitu, epoki miedzi, epoki brązu i epoki żelaza. Wierzę, że wraz z intensyfikacją badań archeobotanicznych będziemy widzieć coraz więcej dowodów na wykorzystywanie żołędzi jako pokarmu. Ale wierzę, że nawet to wystarczy, aby to udowodnić. Wszystkie odniesienia do oryginalnych dokumentów zawierających dane o żołędziach na stanowiskach archeologicznych są wymienione na końcu wpisu wraz z klikalnymi linkami.

I will present the data according to the region. I decided to do that because a lot of the archaeological sites had been occupied over thousands of years and it would be impossible to put them into any one time period. Also presenting the archaeological data according to the region shows that people from certain areas liked eating acorns more than people from other areas and kept eating them over the period of thousands of years spanning multiple cultures. Which opens a question whether acorn eating is linked to a particular tribal of genetic populations.

Przedstawię dane według regionu. Zdecydowałem się na to, ponieważ wiele stanowisk archeologicznych było zamieszkanych przez tysiące lat i niemożliwe byłoby umieszczenie ich w jednym okresie. Również przedstawienie danych archeologicznych według regionu pokazuje, że ludzie z niektórych obszarów lubili jeść żołędzie bardziej niż ludzie z innych obszarów i jedli je przez tysiące lat obejmujących wiele kultur. Co otwiera pytanie, czy jedzenie żołędzi jest powiązane z konkretnym plemieniem populacji genetycznych.

It is also very interesting that I could not find any data for acorns being found on the sites of the Yamna culture and Cucuteni Trypillian cultre. Why? Did I just miss the available data or were these two cultures different from the rest of the Old European cultures? Is it because these two cultures were the true Steppe cultures as opposed to all the other European cultures which were forest cultures?

I also could not find any data for acorns being found on the sites in Britain and Ireland. Again did I just miss the available data or are Britain and Ireland in some way different from the rest of Europe?

I would greatly appreciate any help in answering these two questions.

Bardzo interesujące jest również to, że nie udało mi się znaleźć żadnych danych dotyczących występowania żołędzi na stanowiskach kultury Yamna i kultury Cucuteni Trypillian. Dlaczego? Czy po prostu przegapiłem dostępne dane, czy też te dwie kultury różniły się od reszty kultur Starej Europy? Czy dlatego, że te dwie kultury były prawdziwymi kulturami stepowymi, w przeciwieństwie do wszystkich innych kultur europejskich, które były kulturami leśnymi? Nie mogłem również znaleźć żadnych danych dotyczących żołędzi znalezionych na stanowiskach w Wielkiej Brytanii i Irlandii. Znowu, czy po prostu przegapiłem dostępne dane, czy też Wielka Brytania i Irlandia różnią się w jakiś sposób od reszty Europy? Byłbym bardzo wdzięczny za pomoc w odpowiedzi na te dwa pytania.

Near East

Bliski Wschód

The earliest proof we have that acorns were used as human food are found in middle east at the Gesher Benot Yaaqov Paleolithic site [1].

Najwcześniejsze dowody na to, że żołędzie były używane jako pokarm dla ludzi, znajdują się na Bliskim Wschodzie w paleolicie Gesher Benot Yaaqov [1].

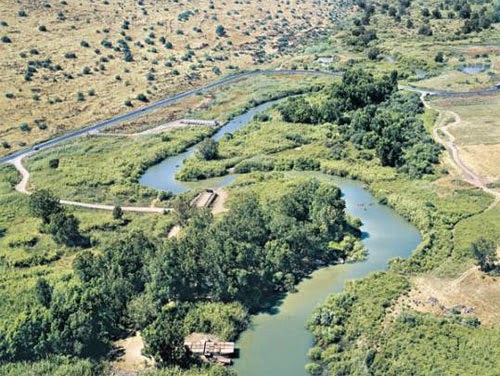

Gesher Benot Yaaqov is located on the shores of the paleo lake Hula in the northern Jordan Valley in the Dead Sea Rift. The site was used by humans for about 100,000 years until 790,000 BC. Fourteen archaeological horizons indicate that Acheulian humans repeatedly occupied the lake margins, where they skillfully produced stone tools, systematically butchered and exploited animals, gathered plant food, and controlled fire. The nut remains found in Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site and dated to about 750 000 BC, are mostly those of Atlantic pistachio, acorns of Mt. Tabor Oak, and wild almonds. They are thought to have been consumed by humans.

Gesher Benot Yaaqov znajduje się nad brzegiem paleo jeziora Hula w północnej Dolinie Jordanu w szczelinie Morza Martwego. Siedlisko było używane przez ludzi przez około 100 000 lat, aż do 790 000 pne. Czternaście horyzontów archeologicznych wskazuje, że ludzie acheulscy wielokrotnie zamieszkiwali brzegi jeziora, gdzie umiejętnie wytwarzali kamienne narzędzia, systematycznie zabijali i eksploatowali zwierzęta, zbierali pokarm roślinny i kontrolowali ogień. Pozostałości orzechów znalezione na stanowisku Gesher Benot Ya’aqov i datowane na około 750 000 pne to głównie pistacje atlantyckie, żołędzie dębu Tabor i dzikie migdały. Uważa się, że były jedzone przez ludzi.

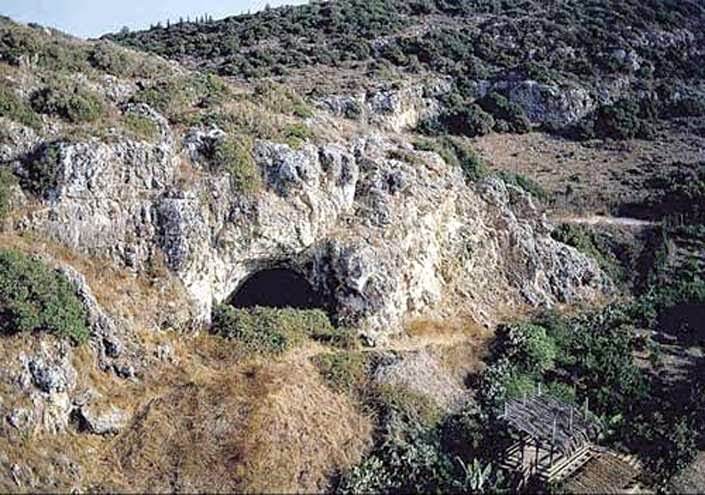

Kebara cave is a limestone cave situated at 60 – 65 metres ASL on the western escarpment of the Carmel Range, in the Ramat Hanadiv preserve of Zichron Yaakov.

Jaskinia Kebara to wapienna jaskinia położona na wysokości 60 – 65 m n.p.m. na zachodnim zboczu pasma Karmel, w rezerwacie Ramat Hanadiv Zichrona Yaakova.

The cave was inhabited between 60,000 – 48,000 BC. Acorns, pistachios and legumes were found in Middle Paleolithic layers [2] dated to about 60 000 BC – 40 000 BC. Kebara cave was at that time occupied by Neanderthals which shows that they too used acorns as food.

Jaskinia była zamieszkana w latach 60 000 – 48 000 pne. Żołędzie, pistacje i rośliny strączkowe znaleziono w warstwach środkowego paleolitu [2] datowanych na około 60 000 pne – 40 000 pne. Jaskinia Kebara była w tym czasie zamieszkana przez neandertalczyków, co świadczy o tym, że oni również używali żołędzi jako pożywienia.

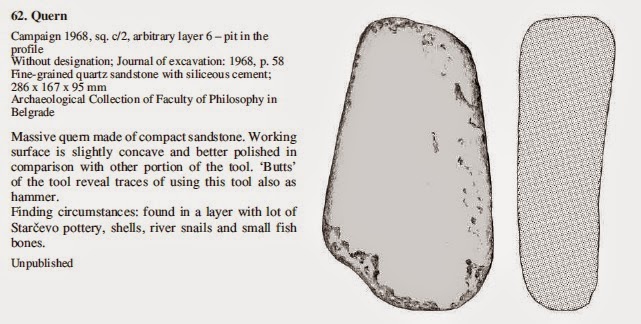

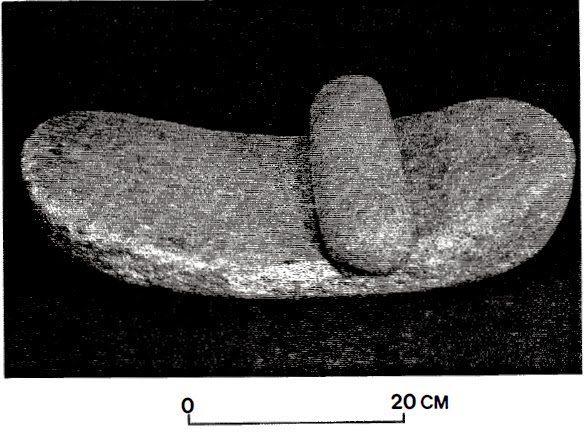

We see that people were still eating acorns at the time of the Last Glacial Maximum. Acorns, legumes and several other plants were reported [3] at Ohalo II site in Israel. Ohalo is an archaeological site in the vicinity of the Sea of Galilee inhabited by hunter gatherers around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum, dated to about 17,400 BC. Ohalo is one of the best preserved hunter-gatherer archaeological sites of that period, and is extremely significant because of the numerous well preserved fruit, nut, acorn and cereal grain remains as well as grinding stones [4], which are confirming that plant and particularly starch food played a significant part of the Paleolithic people’s diet.

Widzimy, że ludzie nadal jedli żołędzie w czasie ostatniego maksimum zlodowacenia. Żołędzie, rośliny strączkowe i kilka innych roślin odnotowano [3] na stanowisku Ohalo II w Izraelu. Ohalo to stanowisko archeologiczne w pobliżu Jeziora Galilejskiego, zamieszkane przez łowców-zbieraczy w okresie maksimum ostatniego zlodowacenia, datowanego na około 17 400 lat pne. Ohalo jest jednym z najlepiej zachowanych stanowisk archeologicznych łowiecko-zbierackich z tego okresu i jest niezwykle ważne ze względu na liczne dobrze zachowane szczątki owoców, orzechów, żołędzi i ziaren zbóż oraz kamienie szlifierskie [4], które potwierdzają, że rośliny i szczególnie skrobia odgrywała znaczącą rolę w diecie ludu paleolitu.

Acorns were next found at the sites of the Natufian culture [5]. The Natufian culture was an Epipaleolithic culture that existed from 13,000 to 9,800 BC. It was unusual in that it was sedentary, or semi-sedentary, before the introduction of agriculture. The Natufian communities are possibly the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region. There is some evidence for the deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture, at the Tell Abu Hureyra site, the site for earliest evidence of agriculture in the world. Generally, though, Natufians made use of wild cereals. Tools for food acquisition, such as sickles, and food processors, such as mortars, bowls, and pestles, are interpreted as evidence for harvesting and processing wild cereals and legumes. But mortars, bowls, and pestles could also have been used for grinding, storing and eating of acorns.

Następnie żołędzie znaleziono na stanowiskach kultury natufijskiej [5]. Kultura natufijska była kulturą epipaleolitu, która istniała od 13 000 do 9800 pne. Rozumiemy to zwykle w tym sensie, że przed wprowadzeniem rolnictwa prowadziło się osiadły lub pół-osiadły tryb życia. Społeczności natufijskie są prawdopodobnie przodkami budowniczych pierwszych osad neolitycznych w regionie. Istnieją pewne dowody na celową uprawę zbóż, w szczególności żyta, przez kulturę natufijską w miejscu Tell Abu Hureyra, miejscu, w którym znajdują się najwcześniejsze dowody rolnictwa na świecie. Na ogół jednak Natufianie korzystali z dzikich zbóż. Narzędzia do pozyskiwania żywności, takie jak sierpy i narządzia kuchenne, takie jak moździerze, miski i tłuczki, są interpretowane jako dowody na zbieranie i przetwarzanie dzikich zbóż i roślin strączkowych. Ale moździerze, miski i tłuczki mogły być również używane do mielenia, przechowywania i jadalnych żołędzi.

The few available seeds support the contention that pulses, cereals, almonds, acorns, and other fruits were gathered.

Nieliczne dostępne nasiona potwierdzają twierdzenie, że zbierano rośliny strączkowe, zboża, migdały, żołędzie i inne owoce.

Trees yielding hard-shell fruits were part of the former landscape of the Southern Levant. Among these, oaks were one of the most prominent features of the Mediterranean woodlands, covering large parts of the landscape. Nevertheless, their possible importance as a food source in past economies of the Southern Levant has been underestimated in comparison to other plant resources. Furthermore, the appearance of stone pounding and grinding tools (frequently mentioned in ethnographic accounts as acorn processing tools) in the Epipalaeolithic and the Early Neolithic has been mostly seen as associated with cereal processing and the transition to agriculture based economies. But there is a strong suggestion that they were indeed used for processing of acorns into flour. [10]

Drzewa dające twarde owoce były częścią dawnego krajobrazu południowego Lewantu. Wśród nich dęby były jedną z najbardziej wyróżniających się cech śródziemnomorskich lasów, pokrywając duże części krajobrazu. Niemniej jednak ich ewentualne znaczenie jako źródła pożywienia w dawnych gospodarkach południowego Lewantu było niedoceniane w porównaniu z innymi zasobami roślinnymi. Ponadto pojawienie się narzędzi do tłuczenia i mielenia kamienia (często wymienianych w relacjach etnograficznych jako narzędzia do obróbki żołędzi) w epipaleolicie i wczesnym neolicie było głównie postrzegane jako związane z przetwarzaniem zbóż i przejściem do gospodarek opartych na rolnictwie. Istnieje jednak silna sugestia, że rzeczywiście były one używane do przetwarzania żołędzi na mąkę. [10]

In Mesolithic villages from the Zagros mountains which form the border between Iran and Iraq, dated to 9000 BC, tools used in the preparation of starch plant food, such as U-shaped mortars and pestles, bone sickle-hafts (but no blades with a gloss along the edge) were found. [11] In the absence of any carbonised grains it is, however, impossible to say whether wild cereals were reaped and processed in grinding stones, or whether other foods such as acorns was processed, considering how abundant acorns were in the area. The find, in the Shanidar cave, of fragments of matting or basketry, the oldest yet known, suggests that collecting baskets may have been used. [12]

W mezolitycznych wioskach z gór Zagros, które tworzą granicę między Iranem a Irakiem, datowanych na 9000 lat p.n.e., narzędzia używane do przygotowywania skrobiowego pokarmu roślinnego, takie jak moździerze i tłuczki w kształcie litery U, sierpowate kościane trzonki (ale bez ostrzy z połyskiem wzdłuż krawędzi). [11] Ze względu na brak jakichkolwiek karbonizowanych ziaren nie można jednak powiedzieć, czy dzikie zboża były zbierane i przetwarzane w kamieniach młyńskich, czy też przetwarzano nimi inne produkty spożywcze, takie jak żołędzie, biorąc pod uwagę obfitość żołędzi na tym obszarze. Znalezisko w jaskini Shanidar fragmentów maty lub wyrobów plecionkarskich, najstarszych znanych, sugeruje, że mogły być używane jako kosze do zbierania. [12]

The Upper Tigris Valley, in the Anatolian part of the Fertile Crescent, has indisputable significance for the early Neolithic in terms of the opportunities it provided for the permanent settlement of human communities. One of these settlements is Körtik Tepe, located in the province of Diyarbakir, near Pinarbasi, at the hamlet of the village called Agil, close to where the Batman Creek joins the Tigris. [78]

Dolina Górnego Tygrysu, położona w anatolijskiej części Żyznego Półksiężyca, ma dla wczesnego neolitu niepodważalne znaczenie ze względu na możliwości stałego osadnictwa społeczności ludzkich. Jedną z takich osad jest Körtik Tepe, położona w prowincji Diyarbakir, niedaleko Pinarbasi, w wiosce Agil, niedaleko miejsca, gdzie Batman Creek łączy się z Tygrysem. [78]

Archaeological excavations in the mound commenced in 2000 and are still ongoing. The archaeological data demonstrate that the Upper Tigris Valley was one of the primary regions of the Near East for the establishment of the earliest permanent settlements. In contrast to the communities leading a nomadic lifestyle, in Körtik Tepe food production technologies were developed and fishing was a common activity. There is also evidence for weaving and architectural units were clearly built for the purpose of storing food. The site is famous for its stone ware made from chlorite stone. [79]

Wykopaliska archeologiczne na kopcu rozpoczęto w 2000 roku i trwają do dziś. Dane archeologiczne wskazują, że Dolina Górnego Tygrysu była jednym z głównych regionów Bliskiego Wschodu, w którym powstały najwcześniejsze stałe osady. W przeciwieństwie do społeczności prowadzących koczowniczy tryb życia, w Körtik Tepe rozwinęły się technologie produkcji żywności, a rybołówstwo było powszechną działalnością. Istnieją również dowody na to, że jednostki tkackie i architektoniczne zostały wyraźnie zbudowane w celu przechowywania żywności. Miejsce to słynie z wyrobów kamiennych wykonanych z chlorytu. [79]

Taking the evidence from the different studies altogether, it has been suggested that the people of Körtik Tepe used a wide spectrum of freshwater animals and hygrophilous plants for their subsistence, personal adornments, and equipment. A mix of hunted large and small animals and wild plants seems to have provided the main calorific input. The results corroborate the findings of other contemporaneous sites where an opportunistic use of plants and animals could be demonstrated. So it is suggested that the intensive, probably year-round permanent use of the site is not due to the intensive use or even cultivation of cereals. Rather, it seems that highly valued and/or calorie-rich resources such as acorns, pistachios, hackberry, and probably almonds, as well as easy to catch small animals like tortoises or fish, contributed to the diet. The rich and diversified environment made the site attractive for a permanent settlement. A specialization on cereals could not be observed so far. The interpretation of plant remains has long been biased by our modern perspective, where the focus on cereals as one of the basic nutritional elements has been projected onto the past. [80]

Łącznie biorąc dowody z różnych badań, zasugerowano, że mieszkańcy Körtik Tepe używali szerokiego spektrum zwierząt słodkowodnych i roślin higrofilnych do utrzymania, ozdób osobistych i wyposażenia. Wydaje się, że główny wkład kaloryczny stanowiła mieszanka upolowanych dużych i małych zwierząt oraz dzikich roślin. Wyniki potwierdzają ustalenia innych współczesnych miejsc, w których można było wykazać pasywne wykorzystanie roślin i zwierząt. Sugeruje się więc, że intensywne, prawdopodobnie całoroczne, stałe użytkowanie stanowiska nie jest spowodowane intensywnym użytkowaniem, a nawet uprawą zbóż. Wydaje się raczej, że wysoko cenione i/lub bogate w kalorie zasoby, takie jak żołędzie, pistacje, jeżyna i prawdopodobnie migdały, a także łatwe do złapania małe zwierzęta, takie jak żółwie czy ryby, przyczyniły się do diety. Bogate i zróżnicowane środowisko czyniło to miejsce atrakcyjnym miejscem stałego osadnictwa. Dotychczas nie można było zaobserwować specjalizacji w zbożach. Interpretacja szczątków roślin od dawna jest obciążona naszą współczesną perspektywą, w której skupienie się na zbożach jako jednym z podstawowych składników odżywczych było rzutowane na przeszłość. [80]

Jarmo is an archaeological site located in northern Iraq on the foothills of Zagros Mountains east of Kirkuk city. Jarmo site represents something new in the prehistory of Iraq: a fully sedentary agricultural village growing (and not merely reaping) emmer wheat, still morphologically close to the wild form, but already accompanied by Einkorn wheat, as well as hulled two row barley (also close to the wild ancestor) at a date c. 6500 BC. Lentils, field peas, blue vetchling were also grown and pistachios and acorns were still collected for their fat contents. Among the animals, goat and dog and perhaps pig were domesticated, but not sheep, or cattle, which were hunted together with gazelle and wild boar. Snails still formed part of the diet. [11]

Jarmo to stanowisko archeologiczne położone w północnym Iraku u podnóża gór Zagros na wschód od miasta Kirkuk. Stanowisko Jarmo reprezentuje coś nowego w prehistorii Iraku: w pełni osiadłą wioskę rolniczą, w której uprawia się (a nie tylko zbiera) pszenicę płaskurka, wciąż morfologicznie zbliżoną do formy dzikiej, ale której towarzyszy już pszenica samopsza, a także jęczmień oplewiony dwurzędowy (również blisko dzikiego przodka) w dacie c. 6500 pne. Soczewica, groszek polny, uprawiano również wykę niebieską starej odmiany, a pistacje i żołędzie nadal zbierano ze względu na zawartość tłuszczu. Wśród zwierząt udomowiono kozę, psa i być może świnię, ale nie owce czy bydło, na które polowano łowiąc je razem z gazelą i dzikiem. Ślimaki nadal stanowiły część diety. [11]

In Anatolia Catal Huyuk was a neolithic city site covering 32 acres and dated to between 6700—5700 BC, which may have housed a population of ten thousand people.

W Anatolii Catal Huyuk było neolitycznym miastem o powierzchni 32 akrów, datowanym na lata 6700-5700 pne, które mogło zamieszkiwać dziesięć tysięcy ludzi.

The economy of this vast site, was based on hunting, advanced agriculture, stock-breeding and probably trade. Sheep, goat and dog were domestic, but the importance of hunting was not thereby diminished. Wild cattle, wild sheep, onager, half-ass, red, roe and fallow deer, ibex, wild boar, bear, hare, leopards,2 and various birds, such as black crane, were hunted, but fishing in the river was less important. Agriculture had made tremendous strides forward during the seventh millennium and the rich deposits of level VI yield three forms of wheat (emmer, einkorn and bread wheat), two forms of barley (naked six-row barley and two-row barley), two sorts of peas, lentils, bitter vetch, crucifers grown for vegetable oil, as well as apple, almonds, hack berry, juniper berries, acorns, pistachio, imported from the hills. [11] This is the most varied diet known from any Near Eastern neolithic site. The archeobotany report published in 1999 says that acorn cup and cotyledon fragments were also identified sparsely, but regularly, in the samples. [13]

Gospodarka tego rozległego obszaru opierała się na łowiectwie, zaawansowanym rolnictwie, hodowli bydła i prawdopodobnie handlu. Owce, kozy i psy były zwierzętami domowymi, ale nie zmniejszyło to znaczenia myślistwa. Polowano na dzikie bydło, dzikie owce, onagery, półosły, jelenie rude, sarny i daniele, koziorożce, dziki, niedźwiedzie, zające, lamparty [2] i różne ptaki, takie jak żuraw czarny, ale połowy w rzece były mniej ważne. W siódmym tysiącleciu rolnictwo poczyniło ogromne postępy, a bogate złoża poziomu VI dają trzy formy pszenicy (płaskurka, samopsza i pszenica zwyczajna), dwie formy jęczmienia (jęczmień nagi sześciorzędowy i dwurzędowy), dwa rodzaje grochu, soczewicy, wyki gorzkiej, roślin krzyżowych uprawianych na olej roślinny, a także jabłek, migdałów, siekaczy, jagód jałowca, żołędzi, pistacji, sprowadzanych z gór. [11] Jest to najbardziej zróżnicowana dieta znana ze wszystkich neolitycznych stanowisk na Bliskim Wschodzie. Raport archeobotaniczny opublikowany w 1999 roku mówi, że fragmenty kielicha żołędzi i liścieni również były identyfikowane rzadko, ale regularnie, w próbkach. [13]

At the late Neolithic settlement at Hacilar IX—VI, some two hundred miles farther west from Catalhuyuk, dated to 5700 BC. we find Late Neolithic arrivals, either people from Catalhuyuk or from the Pisidian lake district, which during the previous period had shown some sort of western variant of the Catalhuyuk culture. The economy of the settlement is mainly agricultural and a continuation of that of Catal Huyuk: emmer, einkorn, bread wheat, naked six-row barley, two sorts of peas, lentils, and also chick-peas, as well as acorns, hack berries, etc. Chert blades are set in curved antler-sickles. Hunting had declined, sheep and goat are probably domesticated, cattle and pig appear, whether or not domesticated; the dog is known. [11]

W późnoneolitycznej osadzie w Hacilar IX-VI, około dwustu mil dalej na zachód od Catalhuyuk, datowanej na 5700 pne. znajdujemy przybyszów z późnego neolitu, albo ludzi z Catalhuyuk, albo z Pojezierza Pizydyjskiego, którzy w poprzednim okresie wykazywali jakiś zachodni wariant kultury Catalhuyuk. Gospodarka osady jest głównie rolnicza i jest kontynuacją gospodarki Catal Huyuk: płaskurka, samopsza, pszenica chlebowa, jęczmień nagi sześciorzędowy, dwa rodzaje grochu, soczewica, a także ciecierzyca, a także żołędzie, siekane jagody itp. Ostrza Chert są osadzone w zakrzywionych sierpach poroża. Zakres łowiectwa spada, owce i kozy są prawdopodobnie udomowione, pojawia się bydło i świnie, udomowione lub nie; pies jest znany. [11]

Viticulture may well have begun either near the Caspian or in a region including Colchis, where at two sites dating to the fourth millennium BC the earliest material evidence has been found, in the form of grape-pips. They were found in accumulations associated with stores of chestnuts, hazelnuts and acorns, these too being for food, at the same sites. These accumulations could indeed have been the outcome of food-gathering rather than of harvesting of cultivated vines [8].

Uprawa winorośli mogła równie dobrze rozpocząć się w pobliżu Morza Kaspijskiego lub w regionie obejmującym Kolchidę, gdzie w dwóch miejscach datowanych na czwarte tysiąclecie pne znaleziono najwcześniejsze dowody materialne w postaci pestek winogron. Znaleziono je w skupiskach związanych z magazynami kasztanów, orzechów laskowych i żołędzi, które również były przeznaczone na żywność, w tych samych miejscach. Te nagromadzenia rzeczywiście mogły być wynikiem zbierania żywności, a nie zbioru uprawianej winorośli [8].

Recent archaeobotanical research from third to second millennium BC Tell Mozan in the Upper Khabur Area, NE Syria, shows a dominating presence of deciduous oak charcoal in most of the samples. Therefore oak park woodland probably had a more southwards distribution during the Early Bronze Age than today. That oak was probably locally present is supported through the find of charcoal from small branches and acorns [9].

Niedawne badania archeobotaniczne od trzeciego do drugiego tysiąclecia pne Tell Mozan w obszarze Górnego Chaburu w północno-wschodniej Syrii wskazują na dominującą obecność węgla drzewnego z dębu liściastego w większości próbek. W związku z tym we wczesnej epoce brązu lasy w parku dębowym były prawdopodobnie rozmieszczone bardziej na południe niż obecnie. O tym, że dąb prawdopodobnie występował lokalnie, świadczy znalezisko węgla drzewnego z małych gałęzi i żołędzi [9].

Africa

Afryka

The earliest evidence of acorn use as food in North Afica is found in the archaeological sites belonging to the upper paleolithic people of Taforalt caves, Morocco, dated to 12,000 BC.

Najwcześniejsze dowody używania żołędzi jako pożywienia w Afryce Północnej znajdują się na stanowiskach archeologicznych należących do ludu górnego paleolitu w jaskiniach Taforalt w Maroku, datowanych na 12 000 pne.

The caves were occupied by people of the Oranian culture which live there during the African Humid Period also known as green Sahara, when the north Africa was a lush green land of forests and grasslands. People of this culture had caries in 51% of adult teeth, a frequency comparable to those of early farmers. [14 ]This is attributed to the very high levels of nut consumption, particularly acorns but also pine nuts, juniper berries, pistachios and wild oats. The number of acorn remains found is so large that the archaeologists had to conclude that they were used as year-long staple. Taforalt people had grinding stones, which they used to process some of these nuts, most likely the acorns, whose consumption as bread has been documented since antiquity.

Jaskinie były zamieszkiwane przez ludność kultury orańskiej, która zamieszkiwała je w okresie wilgotnej Afryki, zwanej też zieloną Saharą, kiedy północna Afryka była bujną, zieloną krainą lasów i łąk. Ludzie z tej kultury mieli próchnicę w 51% zębów dorosłych, z częstotliwością porównywalną do wczesnych rolników. [14 ]Przypisuje się to bardzo wysokiemu poziomowi spożycia orzechów, zwłaszcza żołędzi, ale także orzeszków piniowych, jagód jałowca, pistacji i dzikiego owsa. Liczba znalezionych szczątków żołędzi jest tak duża, że archeolodzy musieli stwierdzić, że były one używane przez cały rok. Mieszkańcy Taforaltów mieli kamienie do mielenia, których używali do obróbki niektórych z tych orzechów, najprawdopodobniej żołędzi, których spożywanie jako chleba zostało udokumentowane od starożytności.

Europe

Iberia

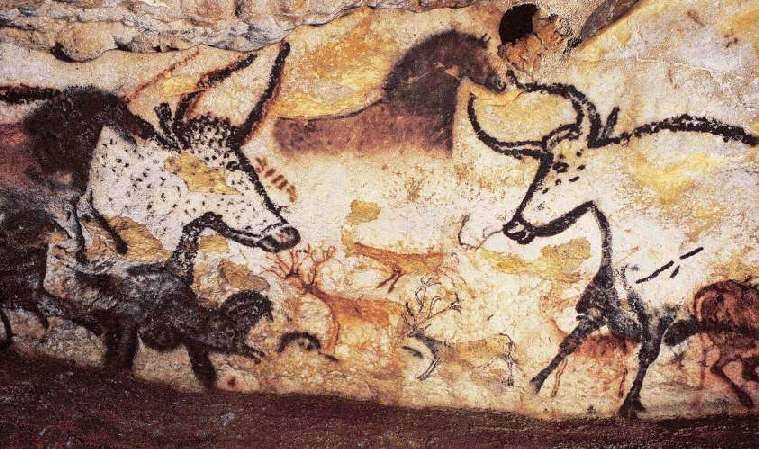

In Europe we find the earliest traces of acorn use in Gravettian culture, a paleolithic people who also left behind spectacular cave paintings, evidence of burial and distinctive stone tools. This is based on the new investigations of an ancient stone recovered in a cave called Grotta Paglicci in Puglia, in southern Italy. [83]

W Europie odnajdujemy najwcześniejsze ślady używania żołędzi w kulturze graweckiej, ludu paleolitu, który również pozostawił po sobie spektakularne malowidła naskalne, dowody pochówku i charakterystyczne kamienne narzędzia. Opiera się to na nowych badaniach starożytnego kamienia znalezionego w jaskini o nazwie Grotta Paglicci w Apulii w południowych Włoszech. [83]

Among many stone tools, the archaeologists have found a stone, which is „pale brown and not much bigger than a hand, ” and which was clearly used as a combination pestle and grinder, says Marta Mariotti Lippi, a botany professor at the University of Florence in Italy, who led the research team. It dates back some 32,000 years, she says, providing the earliest evidence of food processing in Europe.

Wśród wielu kamiennych narzędzi archeolodzy znaleźli kamień, który jest „jasnobrązowy i niewiele większy od dłoni”, i który był wyraźnie używany jako kombinacja tłuczka i młynka, mówi Marta Mariotti Lippi, profesor botaniki na Uniwersytecie im. Florence we Włoszech, który kierował zespołem badawczym. Mówi, że pochodzi sprzed około 32 000 lat, dostarczając najwcześniejszych dowodów przetwarzania żywności w Europie.

„There are many other grinding tools, but this is the oldest,” she says.

„Istnieje wiele innych narzędzi rozcierajacych, ale to jest najstarsze” – mówi.

She says these hunter-gatherers used the rounded end of the stone to bash seeds against another rock to break them up. The flat surface of the stone shows the kind of wear that would be produced by grinding the broken seeds into flour.

Mówi, że ci łowcy-zbieracze używali zaokrąglonego końca kamienia roztrzaskując nasiona o inny kamień, aby je rozbić. Płaska powierzchnia kamienia pokazuje rodzaj zużycia, które powstałoby po zmieleniu połamanych nasion na mąkę.

The stone came to light in June 1989, and although well enough studied at the time, two years ago a new team started a fresh study of material from the cave with the latest modern methods.

Kamień ujrzał światło dzienne w czerwcu 1989 roku i chociaż w tamtym czasie był wystarczająco dobrze zbadany, dwa lata temu nowy zespół rozpoczął nowe badania materiału z jaskini przy użyciu najnowszych nowoczesnych metod.

The researchers sealed the stone in plastic to preserve it for future research. But they left exposed small patches that they washed with a gentle stream of water to loosen debris. In the water were hundreds of starch granules of five main types. The most plentiful, says Mariotti Lippi, were from oat seeds, almost certainly Avena barbata, a wild species still common across much of Europe. The stone also processed other edible plants, including acorns and relatives of millet.

Naukowcy zamknęli kamień w plastiku, aby zachować go do przyszłych badań. Ale zostawili odsłonięte małe plamy, które przemyli delikatnym strumieniem wody, aby rozluźnić zanieczyszczenia. W wodzie znajdowały się setki granulek skrobi pięciu głównych typów. Najwięcej, mówi Mariotti Lippi, pochodziło z nasion owsa, prawie na pewno Avena barbata, dzikiego gatunku, który wciąż jest powszechny w dużej części Europy. Kamień przetwarzał również inne rośliny jadalne, w tym żołędzie i krewniaki prosa.

The second oldest proof of the use of acorns as food in Europe is found in late Paleolithic Magdalenian sites of northern Iberia. The Magdalenian culture is one of the later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic in western Europe, dating from around 15,000 to 10,000 BC whose remains are found in France and Spain.

Drugi najstarszy dowód wykorzystania żołędzi jako pożywienia w Europie znajduje się na stanowiskach magdaleńskich późnego paleolitu w północnej Iberii. Kultura magdaleńska jest jedną z późniejszych kultur górnego paleolitu w Europie Zachodniej, datowaną na okres od około 15 000 do 10 000 pne, której pozostałości znajdują się we Francji i Hiszpanii.

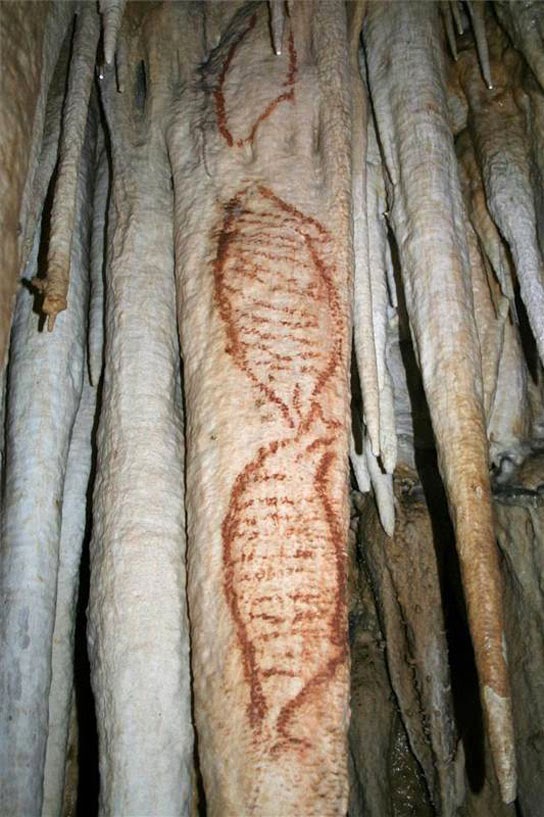

Much of Iberia, especially Mediterranean Spain and Portugal, never experienced dramatically cold extremes except in mountain zones. Because of this a high degree of plant exploitation continued in this part of Europe during the Last glacial maximum. At the Cantabrian Magdalenian site El Juyo, dated to the period 13,988 – 15,179 BC, where climatic and environmental conditions were cooler and the vegetation during the Last Glacial Maximum was less varied, plant macro fossil remains from 21 families and 51 genera were found. These included acorn and hazelnut fragments, berry pits, grass seeds and aquatic plants. Magdalenian and Epipaleolithic levels of Nerja caves, dated to 12 000 BC, also contain acorns and wild olive pits. [15] The food remains from the Nerja cave contain abundant fish remains. This is showing us that by later Magdalenian times there is a dramatic increase in the consumption of aquatic resources. Their number of the remains of the aquatic animals is five times greater than that of rabbits in the Magdalenian, but, in the Preboreal levels, fish outnumber rabbits 10 to 1 and include seals which are actually depicted on the walls of the cave.

Znaczna część Półwyspu Iberyjskiego, zwłaszcza śródziemnomorska Hiszpania i Portugalia, nigdy nie doświadczyła dramatycznie niskich temperatur, z wyjątkiem stref górskich. Z tego powodu wysoki stopień eksploatacji roślin utrzymywał się w tej części Europy podczas maksimum ostatniego zlodowacenia. Na kantabryjskim stanowisku magdaleńskim El Juyo, datowanym na okres 13 988 – 15 179 pne, gdzie warunki klimatyczne i środowiskowe były chłodniejsze, a roślinność podczas maksimum ostatniego zlodowacenia była mniej zróżnicowana, znaleziono makroskamieniałości roślin z 21 rodzin i 51 rodzajów. Obejmowały one fragmenty żołędzi i orzechów laskowych, pestki jagodowe, nasiona traw i rośliny wodne. Poziomy magdaleńskie i epipaleolityczne jaskiń Nerja, datowane na 12 000 pne, zawierają również żołędzie i pestki dzikich oliwek. [15] Pozostałości pożywienia z jaskini Nerja zawierają liczne szczątki ryb. Pokazuje nam to, że w późniejszych czasach magdaleńskich nastąpił dramatyczny wzrost zużycia zasobów wodnych. Liczba szczątków zwierząt wodnych jest pięć razy większa niż królików w okresie magdaleńskim, ale na poziomach preborealnych ryby przewyższają liczebnie króliki 10 do 1 i obejmują foki, które są faktycznie przedstawione na ścianach jaskini.

The collection of sea and land mollusks as well as pine nuts and acorns also is attested to in the Early Mesolithic levels, even if the bulk of food supplies continued to be represented by the meat of red deer and ibex, as in the preceding later Magdalenian.

Zbiór mięczaków morskich i lądowych, a także orzeszków piniowych i żołędzi jest również poświadczony na poziomach wczesnego mezolitu, nawet jeśli większość zapasów żywności nadal stanowiło mięso jelenia i koziorożca, jak w poprzednim i późniejszym okresie magdaleńskim.

The Azilian culture is an Epipaleolithic culture which existed in northern Spain and southern France around 8,000 BC. It succeeded the Magdalenian culture in the same area, and archaeologists even think the Azilian culture could be the tail end of the Magdalenian culture as the warming climate brought about changes in human behaviour in the area. The effects of melting ice sheets would have diminished the food supply and probably impoverished the previously well-fed Magdalenian manufacturers. Acorns, haws, sloes, hazel-nuts, chestnuts, cherries, prunes and walnuts were discovered at the Le Mas d’Azil cave together with a handful of barley-seeds.

Kultura azylijska to kultura epipaleolityczna, która istniała w północnej Hiszpanii i południowej Francji około 8000 pne. Zastąpiła kulturę magdaleńską na tym samym obszarze, a archeolodzy uważają nawet, że kultura azylijska może być końcem kultury magdaleńskiej, ponieważ ocieplający się klimat spowodował zmiany w zachowaniu ludzi na tym obszarze. Skutki topnienia pokryw lodowych zmniejszyłyby zapasy żywności i prawdopodobnie zubożyły wcześniej dobrze odżywionych magdaleńskich wytwórców. Żołędzie, głogi, tarniny, orzechy laskowe, kasztany, wiśnie, suszone śliwki i orzechy włoskie odkryto w jaskini Le Mas d’Azil wraz z garścią nasion jęczmienia.

In Catalunya at Cingle Vermell, dated to 7,760 BC, numerous remains of hazelnuts, acorns, pine nuts, chestnuts and wild fruits have been recovered. [15]

W Catalunya w Cingle Vermell, datowanym na 7760 pne, odzyskano liczne pozostałości orzechów laskowych, żołędzi, orzeszków piniowych, kasztanów i dzikich owoców. [15]

In the Basque country of Spain, Mesolithic and Neolithic wild plant gathering has also been reported. In several sites hazelnuts, acorns and wild tree fruits were common in both periods. One of the most famous sites from Basque country is Epipaleolithic site in València known as La Sarga.

W Kraju Basków w Hiszpanii odnotowano również gromadzenie dzikich roślin w mezolicie i neolicie. Na kilku stanowiskach w obu okresach powszechne były orzechy laskowe, żołędzie i owoce dziko rosnących drzew. Jednym z najbardziej znanych miejsc z Kraju Basków jest epipaleolityczne stanowisko w Walencji, znane jako La Sarga.

At La Sarga , a painted rock art scene shows several figures collecting acorns or hazelnuts as they fall from the tree.

Malowana scena naskalna w La Sarga przedstawia kilka postaci zbierających spadające z drzewa żołędzie lub orzechy laskowe.

Pine nuts, acorns and chestnuts were reported at Cova Fosca dated to 7,460 BC. [18]

Orzeszki piniowe, żołędzie i kasztany odnotowano w Cova Fosca datowane na 7460 pne. [18]

The archaeobotanical material obtained from 24 sites from the Neolithic period (5400–2300 cal BC) in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula was recently analized. Among dry sites, several types of context were evaluated: dwelling areas, hearths, roasting pits and byres. Material was also analysed from a waterlogged cultural layer of one early Neolithic lakeshore site, La Draga. Acorns, hazelnuts, mastic fruits and wild grapes were among the most frequently encountered fruits and seeds. Larger amounts of charred remains of certain wild fruits like acorns and hazelnuts found in mountain areas are highlighted as potential evidence of the regular practise of roasting, potentially indicating regional traditions. [70]

Niedawno przeanalizowano materiał archeobotaniczny pozyskany z 24 stanowisk z okresu neolitu (5400-2300 p.n.e.) w północno-wschodniej części Półwyspu Iberyjskiego. Wśród stanowisk suchych oceniono kilka rodzajów kontekstów: obszary mieszkalne, paleniska, paleniska i obory. Przeanalizowano również materiał z podmokłej warstwy kulturowej jednego z wczesnych neolitycznych stanowisk położonych nad jeziorem, La Draga. Do najczęściej spotykanych owoców i nasion należały żołędzie, orzechy laskowe, owoce mastyksu i dzikie winogrona. Większe ilości zwęglonych szczątków niektórych dzikich owoców, takich jak żołędzie i orzechy laskowe, znalezione na obszarach górskich, są podkreślane jako potencjalny dowód regularnej praktyki prażenia, potencjalnie wskazujący na regionalne tradycje. [70]

La Draga is the only lake-dwelling site that is known in the Iberian Peninsula.

La Draga jest jedynym znanym miejscem zamieszkania nad jeziorem na Półwyspie Iberyjskim.

The main interest of the site is the extraordinary preservation of plant remains both in charred and waterlogged states. The site was occupied at least twice between 5300 and 5000 BC by people of Carded Ware Culture. The first phase of occupation contains remains of cereals, mainly wheat, poppy, and many collected wild plants such as acorns, blackberries and wild grape. Remains of cultivated legumes were not found. [44]

In Portugal, carbonised acorns were reported at the Neolithic site of Ameal, dated to 3500 BC. A concentrations of acorns is reported at the Copper Age site Vila Nova de São Pedro dated to 2600 to 1300 BC.

W Portugalii karbonizowane żołędzie odnotowano w neolitycznym miejscu Ameal, datowanym na 3500 pne. Nasilenie zbiorowisk żołędzi odnotowano w miejscu z epoki miedzi Vila Nova de São Pedro datowanym na 2600 do 1300 pne.

At the Bronze Age settlement at Moncín in north-east Spain, dated to 2600 – 1300 BC, the plant economy was dominated by wheat and barley, with a small contribution from edible wild plants and fruits. Lentils were present, but only rarely. Flax was also found, but whether cultivated or not is not known. The sweet acorns from the Mediterranean holm-oak, were common and they may also have been mixed with wheat for bread. [55]

W osadzie z epoki brązu w Moncín w północno-wschodniej Hiszpanii, datowanej na 2600-1300 pne, gospodarka roślinna była zdominowana przez pszenicę i jęczmień, z niewielkim udziałem jadalnych dzikich roślin i owoców. Soczewica była obecna, ale rzadko. Znaleziono również len, ale nie wiadomo, czy był uprawiany, czy nie. Słodkie żołędzie z śródziemnomorskiego dębu ostrokrzewowego były powszechne i mogły być również mieszane z pszenicą na chleb. [55]

The Castro culture is the Celtic culture of the northwestern regions of the Iberian Peninsula (present-day northern Portugal and the Spanish regions of Galicia, western Asturias and north western León). It existed from the end of the Bronze Age (c. 9th century BC) until it was subsumed by Roman culture (c. 1st century BC).

Kultura Castro to kultura celtycka północno-zachodnich regionów Półwyspu Iberyjskiego (dzisiejsza północna Portugalia i hiszpańskie regiony Galicji, zachodniej Asturii i północno-zachodniego León). Istniała od końca epoki brązu (ok. IX wpne) do czasu podporządkowania jej kulturze rzymskiej (ok. I wpne).

Using three main type of tools, ploughs, sickles and hoes, together with axes for woodcutting, the Castro inhabitants grew a number of cereals: (wheat, millet, possibly also rye) for baking bread, as well as oats, and barley which they also used for beer production. They also grew beans, peas and cabbage, and flax for fabric and clothes production; other vegetables where collected: nettle, watercress. Large quantities of acorns have been found hoarded in most hill-forts, and they were used for bread production once toasted and crushed in granite stone mills.

Za pomocą trzech głównych typów narzędzi, pługów, sierpów i motyk, wraz z siekierami do obróbki drewna, mieszkańcy Castro uprawiali szereg zbóż: (pszenicę, proso, być może także żyto) do wypieku chleba, a także owies i jęczmień, które używano również do produkcji piwa. Uprawiali także fasolę, groch i kapustę oraz len do produkcji tkanin i odzieży; zbierano inne warzywa: pokrzywę, rukiew wodną. W większości osad na wzgórzach znaleziono duże ilości żołędzi, które były używane do produkcji chleba po tostowaniu i kruszeniu w granitowych kamiennych młynach.

Acorns were a staple food in Iberia during late Bronze age as shown by chared acorn remains found in Santinha and and S. Juliao sites in the Cávado Basin dated to the 10th century BC. [63]

Żołędzie były podstawowym pożywieniem na Półwyspie Iberyjskim w późnej epoce brązu, o czym świadczą zwęglone szczątki żołędzi znalezione na stanowiskach Santinha i S. Juliao w dorzeczu Cávado datowane na X wiek pne. [63]

Italy

Włochy

The Grotta dell’Uzzo cave is one of the most important prehistoric sites in Sicily. The earliest human habitaion layers in the cave were dated to 8000 BC.

Jaskinia Grotta dell’Uzzo jest jednym z najważniejszych prehistorycznych miejsc na Sycylii. Najwcześniejsze warstwy siedlisk ludzkich w jaskini datowane są na 8000 pne.

At the this cave, wild peas, acorns, olives, grapes and arbutus fruits were recovered.[19]

W jaskini tej wydobyto dziki groszek, żołędzie, oliwki, winogrona i owoce arbutusa.[19]

Impressive amounts of nuts, acorns, chestnuts, blackberries, wild apples, cornelian cherries, dogwood, grapes were found at Neolithic villages at old Sammardenchia and Fagnigola in Friuli and at Lugo di Romagna in Northern Italy dated to about 6050 BC. [19]

Imponujące ilości orzechów, żołędzi, kasztanów, jeżyn, dzikich jabłek, derenia, glogu, winogron znaleziono w neolitycznych wioskach w starej Sammardenchia i Fagnigola we Friuli oraz w Lugo di Romagna w północnych Włoszech, datowanych na około 6050 pne. [19]

The open-air site Villandro/Villanders in Alto Adige/South Tyrol, was inhabited through Late Mesolithic (Castelnovian) dated to 5970-5680 BC all the way to Early Medieval period. The first settlers here grew Barley and naked Wheat, maybe using the surrounding environment for the collection of wild fruits like Strawberry and Elderberries. During the following occupation in the Middle Neolithic (Square-Mouthed Pottery Culture) the cereal assemblage does not change, but Emmer makes its first appearance. Meanwhile, many more wild fruits were gathered in the woodland, like Blackberries, Raspberries, Acorns and Wild Cherries. The large amount of charred Corylus wood suggests that also hazelnuts were commonly eaten in this period, but no shells were found in these layers. [36]

Teren pod gołym niebem Villandro/Villanders w Górnej Adydze/Południowym Tyrolu był zamieszkany przez późny mezolit (kasztelnowski) datowany na lata 5970-5680 pne aż do okresu wczesnego średniowiecza. Pierwsi osadnicy uprawiali tu jęczmień i nagą pszenicę, być może wykorzystując otaczające środowisko do zbierania dzikich owoców, takich jak poziomki i bzu czarnego. Podczas następnej fazy osiedlenia w środkowym neolicie (kultura ceramiki z kwadratowymi ustami) zespół zbóż nie zmienia się, ale po raz pierwszy pojawia się emmer [CB stary rodzaj pszenicy]. W międzyczasie w lasach zebrano znacznie więcej dzikich owoców, takich jak jeżyny, maliny, żołędzie i dzikie czereśnie. Duża ilość zwęglonego drewna Corylus sugeruje, że w tym okresie powszechnie spożywano także orzechy laskowe, jednak w tych warstwach nie znaleziono łupin. [36]

In the Veneto area in the 5th millennium BC we find Square Mouthed Pottery culture.

W regionie Veneto w V tysiącleciu pne znajdujemy kulturę ceramiki z kwadratowymi ustami.

Their diet was varied. They grew cereals such as barley, emmer wheat, einkorn, naked wheat (common and/or durum/rivet wheat), and the so-called “new glume wheat”. The cultivation of spelt wheat is uncertain, as is the cultivation of millet and they only appear in the later layers from 3rd millennium BC. Flax and poppy, both species deriving from the “initial Neolithic package” coming from the Fertile Crescent, were also found. They eat a lot of oxen and sheep meat with small amount of fish and shelfish. The list of fruit species used as food is relatively extensive: wild grapes, berries of the cornelian cherry and the common dogwood, apples and pears, bladder cherries, blackberries, raspberries, haw-thorn berries, elderberries, wild plums, figs, strawberries. Starchy foods include hazelnuts which are most frequent, acorns, water chestnut and walnuts. There is limited evidence of pulses being eaten, mostly peas and lentils.[39]

Ich dieta była zróżnicowana. Uprawiali zboża, takie jak jęczmień, pszenica płaskurka, samopsza, pszenica naga (zwykła i/lub pszenica durum/nitowana) oraz tzw. „nowa pszenica plewowa”. Uprawa orkiszu jest niepewna, podobnie jak uprawa prosa i pojawiają się one dopiero w późniejszych warstwach z III tysiąclecia pne. Znaleziono także len i mak, oba gatunki pochodzące z „początkowego pakietu neolitycznego” pochodzącego z Żyznego Półksiężyca. Spożywają dużo mięsa wołowego i baraniego z niewielką ilością ryb i skorupiaków szelfowych. Lista gatunków owoców wykorzystywanych jako żywność jest stosunkowo obszerna: dzikie winogrona, jagody derenia i derenia wiśniowego, jabłka i gruszki, wiśnie pęcherzowe, jeżyny, maliny, owoce głogu, czarny bez, dzikie śliwki, figi, truskawki. Do pokarmów bogatych w skrobię należą najczęściej orzechy laskowe, żołędzie, kasztany wodne i orzechy włoskie. Istnieją ograniczone dowody na spożywanie roślin strączkowych, głównie grochu i soczewicy.

In Italy the food remains found in the Bronze age sites are: pears, apples, cornelian cherries and various berries, along with hazelnuts and acorns, accompanied the usual range of grain crops and pulses. Millet appears in the Late Bronze Age, and false flax is also present. Grapes are attested regularly through the Bronze Age. At the Bronze Age site Fiavé-Carera ceramics with charred acorns inside have been found. The acorns were all peeled. [55]

We Włoszech pozostałości pożywienia znalezione na stanowiskach z epoki brązu to: gruszki, jabłka, derenie i różne jagody, a także orzechy laskowe i żołędzie, towarzyszące zwykłemu zakresowi upraw zbożowych i roślin strączkowych. Proso pojawia się w późnej epoce brązu, obecny jest również len fałszywy. Winogrona są regularnie potwierdzane przez epokę brązu. Na stanowisku z epoki brązu znaleziono ceramikę Fiavé-Carera ze zwęglonymi żołędziami w środku. Wszystkie żołędzie były obrane. [55]

In the Bronze Age settlement of Nola in Campania, southern Italy, dated to the 2000 BC many remains of three types of grains (small emmer, spelt and barley) as well as acorns and almonds were found. [19]

W osadzie Nola z epoki brązu w Kampanii w południowych Włoszech, datowanej na 2000 pne, znaleziono wiele pozostałości trzech rodzajów zbóż (płaskurki, orkiszu i jęczmienia), a także żołędzi i migdałów. [19]

The analysis of archaeobotanical assemblages recovered in recent and older archaeological excavations conducted at several sites in southeastern Italy (Apani, Torre Guaceto, Rocavecchia, Melendugno, Piazza Palmieri, Monopoli, Scalo di Furno, Porto Cesareo), have revealed the importance of acorn gathering and use in Bronze Age societies. The charred acorns from Bronze Age sites examined in this study were associated with domestic fireplaces, being found next to griddles and mixed with other edible plants such as cereals, legumes and other edible tree fruits. These observations suggest they played an important part in protohistoric economies. [57]

Analiza zespołów archeobotanicznych odzyskanych podczas niedawnych i starszych wykopalisk archeologicznych prowadzonych na kilku stanowiskach w południowo-wschodnich Włoszech (Apani, Torre Guaceto, Rocavecchia, Melendugno, Piazza Palmieri, Monopoli, Scalo di Furno, Porto Cesareo) ujawniły znaczenie zbierania i wykorzystywania żołędzi w społeczeństwach epoki brązu. Zwęglone żołędzie z miejsc z epoki brązu zanalizowane w tym badaniu były związane z domowymi paleniskami, znajdowano je obok paleniska, jako mieszane z innymi jadalnymi roślinami, takimi jak zboża, rośliny strączkowe i inne jadalne owoce z drzew. Obserwacje te sugerują, że odegrały ważną rolę w gospodarkach protohistorycznych. [57]

Sardinia

The Ozieri culture (or San Michele culture) was a prehistoric pre-Nuragic culture that lived in Sardinia from c. 3200 to 2800 BC. The influence of the culture extended also to the nearby Corsica.

Kultura Ozieri (lub kultura San Michele) była prehistoryczną kulturą przednuragijską, która żyła na Sardynii od ok. 3200 do 2800 pne. Wpływ kultury rozciągał się także na pobliską Korsykę.

During Ozieri period, 3200-2500 BC, we see increase in amount of acorns being found in archaeological sites. This coincides with the period of main diffusion of evergreen oak in the Western Mediterranean, which dates precisely to the 4th and especially 3rd millennium. This is also the time period when a lot of acorns have been recovered in Corsica, and in southern France at Copper Age walled settlements, to which the northern Sardinia Monte Claro sites have commonly been compared. While the use of acorns to feed pigs is widespread in the Mediterranean, their utilisation for bread-making, though rare, was common over wide areas of Sardinia still in the 1700s, and is still known today [7].

W okresie Ozieri, 3200-2500 pne, obserwujemy wzrost ilości znajdowanych żołędzi na stanowiskach archeologicznych. Zbiega się to z okresem głównego rozpowszechnienia wiecznie zielonego dębu w zachodniej części Morza Śródziemnego, który datuje się dokładnie na 4., a zwłaszcza na 3. tysiąclecie. Jest to również okres, w którym wiele żołędzi zostało odzyskanych na Korsyce iw południowej Francji w osadach otoczonych murami z epoki miedzi, do których często porównuje się stanowiska Monte Claro na północnej Sardynii. Podczas gdy wykorzystanie żołędzi do karmienia świń jest szeroko rozpowszechnione w basenie Morza Śródziemnego, ich wykorzystanie do wypieku chleba, choć rzadkie, było powszechne na rozległych obszarach Sardynii jeszcze w XVIII wieku i jest znane do dziś [7].

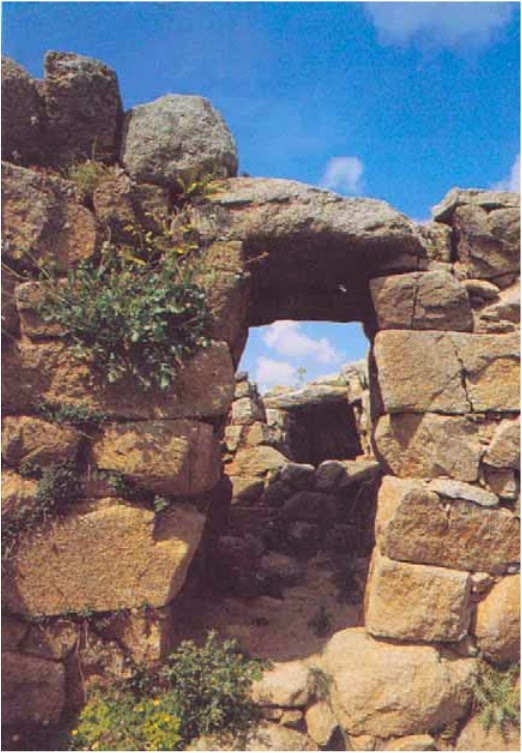

The Nuragic civilisation was a civilization of Sardinia, lasting from the Bronze Age (18th century BC) to the 2nd century AD. The name derives from its most characteristic monuments, the nuraghe. They consist of tower-fortresses, built starting from about 1800 BC. Today some 7,000 nuraghi dot the Sardinian landscape.

Cywilizacja nuragijska była cywilizacją Sardynii, trwającą od epoki brązu (XVIII wiek pne) do II wieku naszej ery. Nazwa wywodzi się od najbardziej charakterystycznych pomników, nuraghe. Składają się z wież-twierdz, budowanych od około 1800 roku pne. Obecnie krajobraz Sardynii pokrywa około 7000 nuraghi.

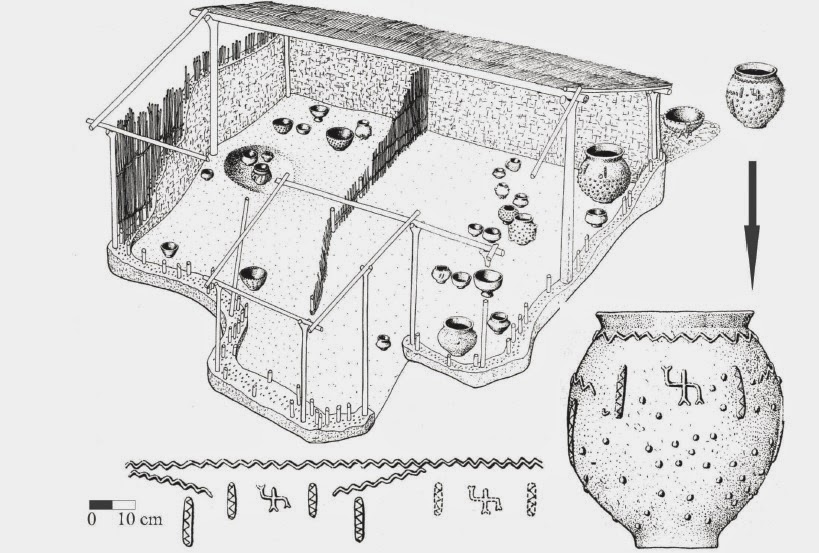

At the Nuraghe Albucciu the cultural layer that corresponds to the first period in the life of the building is the richest in shards and lithics. There are many pots, some with clay disk lids with a hole in the centre, jars with a thick cord lip, carinated and flat-bottomed bowls, pans, loom weights. Among the lithics, we find numerous pestles and grinders. The hearth under the cupboard was no longer used while the large one at the centre of the room continued to be. Many burnt acorns were found around it [6].

W Nuraghe Albucciu warstwa kulturowa odpowiadająca pierwszemu okresowi życia budynku jest najbogatsza w odłamki i lity. Jest wiele garnków, niektóre z glinianymi pokrywkami z krążkami z otworem pośrodku, słoje z grubą kordową warżką, miski karnowane i płaskodenne, patelnie, ciężarki do krosen. Wśród litów znajdziemy liczne tłuczki i rozdrabniacze. Palenisko pod okapem nie było już używane, podczas gdy duże na środku pomieszczenia nadal było używane. Wokół niego znaleziono wiele spalonych żołędzi [6].

Lake dwellings

Osady palowe nad jeziorami

Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps is a series of prehistoric pile-dwelling (or stilt house) settlements in and around the Alps built from around 5000 to 500 B.C. on the edges of lakes, rivers or wetlands. 111 sites, located in Austria (5 sites), France (11 sites), Germany (18 sites), Italy (19 sites), Slovenia (2 sites), and Switzerland (56 sites).

Prehistoryczne domy na palach wokół Alp to seria prehistorycznych osad na palach (lub domów na palach) w Alpach i wokół nich, zbudowanych od około 5000 do 500 pne. na brzegach jezior, rzek lub mokradeł. 111 placówek zlokalizowanych w Austrii (5 placówek), Francji (11 placówek), Niemczech (18 placówek), Włoszech (19 placówek), Słowenii (2 placówki) i Szwajcarii (56 placówek).

It seems that people who lived in these pile dwellings used acorn as one of their main sources of starch. In some of the oldest lake dwellings,notably those of Germany, the only starch food consisted of hazel nuts, acorns, and the water chestnut. [40]

Wydaje się, że ludzie mieszkający w tych domach stosowali żołądź jako jedno z głównych źródeł skrobi. W niektórych najstarszych osadach położonych nad jeziorami, zwłaszcza w Niemczech, jedynym pożywieniem skrobiowym były orzechy laskowe, żołędzie i kasztany wodne. [40]

At the Neolithic (Cortaillod culture) and Bronze Age (La Tene culture) (4400-1570 BC.) pile dwellings of Concise-sous-Colachoz on the shore of Lake Neuchâtel (Canton of Vaud, western Switzerland), the preliminary study of cereal macro fossil remains from all the mentioned Neolithic phases show that the most important cereals were durum,naked wheat, einkorn and barley. Other cultivated plants were pea, flax and opium poppy. Additionally to the seeds, capsule fragments of opium poppy were found in the Cortaillod moyen deposits. Wild fruits which were collected as plant resources included sloe, dogwood, apple, raspberry,dewberry,blackberry, wild strawberry, rose hip, acorn, hazelnut and beechnut, among others. [37]

W neolicie (kultura Cortaillod) i epoce brązu (kultura La Tene) (4400-1570 pne) osadach palowych Concise-sous-Colachoz na brzegu jeziora Neuchâtel (kanton Vaud, zachodnia Szwajcaria), wstępne badania zbóż makroskamieniałości ze wszystkich wspomnianych faz neolitu wskazują, że najważniejszymi zbożami były durum, pszenica naga, samopsza i jęczmień. Inne uprawiane rośliny to groch, len i mak lekarski. Oprócz nasion w osadach Cortaillod moyen znaleziono fragmenty torebek maku lekarskiego. Dzikie owoce zbierane jako zasoby roślinne to m.in. tarnina, dereń, jabłko, malina, popielica, jeżyna, poziomka, dzika róża, żołądź, orzech laskowy i buk. [37]

The oldest Umbrian settlements, such as the pile dwellings in the Lake Fimon, dating from the first half of the 5th millennium BC and belonging to the first phase of Square Mouthed Pottery Culture [41], prove that the Umbrians, when they arrived in Italy, lived chiefly by the chase, but also that they had domesticated the ox and the sheep. Agriculture, even of the rudest description,seems to have been unknown, since no cereals were found. But there were considerable stores of hazel nuts, of water chestnuts, and of acorns, some of which had been already roasted for food. The remains of the settlement in the Lake of Fimon are specially instructive, as it must have been founded very soon after the Umbrians arrived in Italy, and was destroyed before they had passed from the pastoral to the agricultural stage. There are two successive relic beds, the oldest belonging entirely to the neolithic age. The inhabitants did not yet cultivate the soil, but subsisted chiefly by the chase. The bones of the stag and of the wild boar are extremely plentiful, while those of the ox and the sheep are rare. There are no remains of cereals of any kind, but great stores of hazel nuts were found, together with acorns some of them adhering to the inside of the pipkins in which they had been roasted for food. Cereals are still absent, although acorns, hazel nuts, and cornel cherries are found. But the pastoral stage had plainly been reached, since the bones of the stag and the wild boar become rare, while those of the ox and the sheep are common.

Najstarsze osady umbryjskie, takie jak osady na palach w jeziorze Fimon, datowane na pierwszą połowę V tysiąclecia p.n.e. i należące do pierwszej fazy kultury ceramiki z kwadratowymi ustami [41], dowodzą, że Umbryjczycy, kiedy przybyli do Italii , żyli głównie z łowiectwa, ale także z tego, że udomowili wołu i owcę. Rolnictwo, nawet najbardziej prymitywne, wydaje się być nieznane, ponieważ nie znaleziono zbóż. Ale były tam pokaźne zapasy orzechów leszczyny, kasztanów wodnych i żołędzi, z których część była już uprażona na jedzenie. Pozostałości osady w jeziorze Fimon są szczególnie pouczające, ponieważ musiała ona zostać założona bardzo szybko po przybyciu Umbrów do Italii i została zniszczona, zanim przeszli z etapu pasterskiego do rolniczego. Istnieją dwa kolejne pokłady reliktów, z których najstarszy w całości pochodzi z epoki neolitu. Mieszkańcy nie uprawiali jeszcze roli, żyli głównie z polowania. Kości jelenia i dzika są niezwykle obfite, podczas gdy kości wołu i owcy są rzadkie. Nie ma żadnych pozostałości zbóż, ale znaleziono wielkie zapasy orzechów leszczyny, wraz z żołędziami, niektóre z nich przylegały do wnętrza dyni, w których były prażone. Nadal nie ma zbóż, chociaż można znaleźć żołędzie, orzechy laskowe i owoce derenia wiśniowego. Ale etap pasterski najwyraźniej został osiągnięty, ponieważ kości jelenia i dzika stają się rzadkie, podczas gdy kości wołu i owcy są powszechne.

In the pile dwellings at Ljubljana in Slovenia both flax and grain are absent,but hazel nuts in enormous quantities were found, together with the kernels of the water chestnut. At Hočevarica an eneolithic pile dwelling site in the Ljubljana marshes, dated to 3640-3520 BC together with the cereal remains (rye and wheat), many wild plant food remains were found too: acorns, grapes, cornel-cherry, raspberries, water chestnuts, poppy seeds, hazelnuts, etc. [74]

W domach na palach w Lublanie w Słowenii nie ma ani lnu, ani zboża, ale znaleziono orzechy laskowe w ogromnych ilościach wraz z jądrami kasztanowca wodnego. W Hočevarica, eneolitycznym miejscu zamieszkania na palach na bagnach Lublany, datowanym na 3640-3520 pne wraz z resztkami zbóż (żyta i pszenicy), znaleziono również wiele szczątków pokarmu dzikich roślin: żołędzie, winogrona, dereń, maliny, kasztany wodne , mak, orzechy laskowe itp. [74]

In Switcerland, the food remains found in Bronze age sites show that grain crops consisted of several sorts of wheat (emmer, einkorn, bread wheat and spelt), barley and three sorts of millet including broomcorn millet. Then there were oil plants (poppy and flax), and legumes, peas, beans and lentils. Wild fruits found are apples, raspberries, blackberries, strawberries, pears, sloes, rose-hips, elderberries and nuts (acorn, hazel and beech), as well as various other species which could have been eaten, though they are not primary food plants. At the Bronze Age sites Hauterive-Champréveyres and Zug-Sumpf ceramics with charred acorns inside have been found. The acorns were all peeled. [55]

W Szwajcarii pozostałości pożywienia znalezione na stanowiskach z epoki brązu wskazują, że zboża składały się z kilku rodzajów pszenicy (płaskurka, samopsza, pszenica chlebowa i orkisz), jęczmienia i trzech rodzajów prosa, w tym prosa janowca. Potem były rośliny oleiste (mak i len) oraz rośliny strączkowe, groch, fasola i soczewica. Dzikie owoce to jabłka, maliny, jeżyny, truskawki, gruszki, tarniny, owoce dzikiej róży, czarny bez i orzechy (żołądź, leszczyna i buk), a także różne inne gatunki, które można było jeść, choć nie są podstawowymi roślinami pokarmowymi . Na stanowiskach z epoki brązu znaleziono ceramikę Hauterive-Champréveyres i Zug-Sumpf ze zwęglonymi żołędziami w środku. Wszystkie żołędzie były obrane. [55]

At La Marmotta, a few hundred meters outside the village of Anguillara Sabazia, remains of an Early Neolithic lakeshore village, datable 5700 BCE have been found.

W La Marmotta, kilkaset metrów od wioski Anguillara Sabazia, znaleziono pozostałości wioski nad jeziorem z wczesnego neolitu, datowanej na 5700 pne.

The strongest evidence that the Marmottans came from far away, is simply that their culture was advanced from the start. In the region around Lake Bracciano, according to Fugazzola Delpino, there is no sign of any but hunter-gatherers before the settlement was built at La Marmotta. The builders of the village had at their disposal, from the start, the entire „Neolithic package”: domesticated animals and plants, ceramic pots, polished stone tools, just as though they had unloaded all those things from their boats. They kept sheep and goats; they brought pigs and cows with them too, and two breeds of dog, and they planted a wide variety of crops, wheat and barley and legumes. They also collected fruit, apples, plums, raspberries, strawberries. Especially in winter they supplemented their diet with acorns, which they stored in large ceramic jars.

Najmocniejszym dowodem na to, że Marmottanowie przybyli z daleka, jest po prostu to, że ich kultura była zaawansowana od samego początku. W regionie wokół jeziora Bracciano, według Fugazzola Delpino, nie ma żadnych śladów poza łowcami-zbieraczami, zanim osada została zbudowana w La Marmotta. Budowniczowie wioski mieli od początku do dyspozycji cały „neolityczny pakiet”: udomowione zwierzęta i rośliny, ceramiczne garnki, narzędzia z polerowanego kamienia, tak jakby wyładowali to wszystko ze swoich łodzi. Hodowali owce i kozy; przywieźli też ze sobą świnie i krowy oraz dwie rasy psów i zasadzili różnorodne uprawy, pszenicę, jęczmień i rośliny strączkowe. Zbierano także owoce, jabłka, śliwki, maliny, truskawki. Szczególnie zimą uzupełniali swoją dietę żołędziami, które przechowywali w dużych ceramicznych słojach.

They cultivated flax to make linen and planted opium poppies.

Uprawiali len na płótno i sadzili mak opiumowy.

Atlantic

Wybrzeże Atlantyku

Charred acorns have been found at several Late Mesolithic sites at Doel (Belgium) dated to between 7500 BC and 3000 BC , together with a variety of other collected wild plants. [64]

Zwęglone żołędzie znaleziono na kilku stanowiskach późnego mezolitu w Doel (Belgia) datowanych na okres między 7500 pne a 3000 pne, wraz z wieloma innymi zebranymi dzikimi roślinami. [64]

Swifterbant culture was a Mesolithic archaeological culture in the Netherlands, dated between 5300 BC and 3400 BC. Like the Ertebølle culture, the settlements were concentrated near water, in this case creeks, river dunes and bogs along post-glacial banks of rivers like the Overijsselse Vecht. Hazelnuts and acorns were discovered in hearths at the Swifterbant site. At another Swifterbant culture site at Polderweg dated to the latter part of the sixth millennium BC. Throughout this period the main activity appears to have been pike fishing, probably undertaken during the second half of the winter. Roach, bream, tench, eels, catfish, and salmon also were caught, probably through the use of sophisticated traps. Beaver and otter were the most important mammals, probably trapped for their pelts, as were pine marten, wild cat, and polecat. The remains of wild boar and red and roe deer also were present in the assemblage. Fowling concentrated on ducks, and plant resources comprised acorns, hazelnut, water nut, wild apple, and various berries. [53]

Kultura Swifterbant była mezolityczną kulturą archeologiczną w Holandii, datowaną na okres między 5300 pne a 3400 pne. Podobnie jak kultura Ertebølle, osady były skoncentrowane w pobliżu wody, w tym przypadku potoków, wydm rzecznych i torfowisk wzdłuż polodowcowych brzegów rzek, takich jak Overijsselse Vecht. Orzechy laskowe i żołędzie odkryto w paleniskach na stanowisku Swifterbant. W innym miejscu kultury Swifterbant w Polderweg datowanym na drugą część szóstego tysiąclecia pne. Wydaje się, że przez cały ten okres głównym zajęciem było łowienie szczupaków, podejmowane prawdopodobnie w drugiej połowie zimy. Łowiono również płocie, leszcze, liny, węgorze, sumy i łososie, prawdopodobnie przy użyciu wyrafinowanych pułapek. Najważniejszymi ssakami były bóbr i wydra, prawdopodobnie schwytane dla skór, podobnie jak kuna leśna, żbik i tchórz. W zbiorowisku obecne były także szczątki dzika oraz jelenia i sarny. Ptactwo koncentrowało się na kaczkach, a zasoby roślinne obejmowały żołędzie, orzechy laskowe, orzechy wodne, dzikie jabłka i różne jagody. [53]

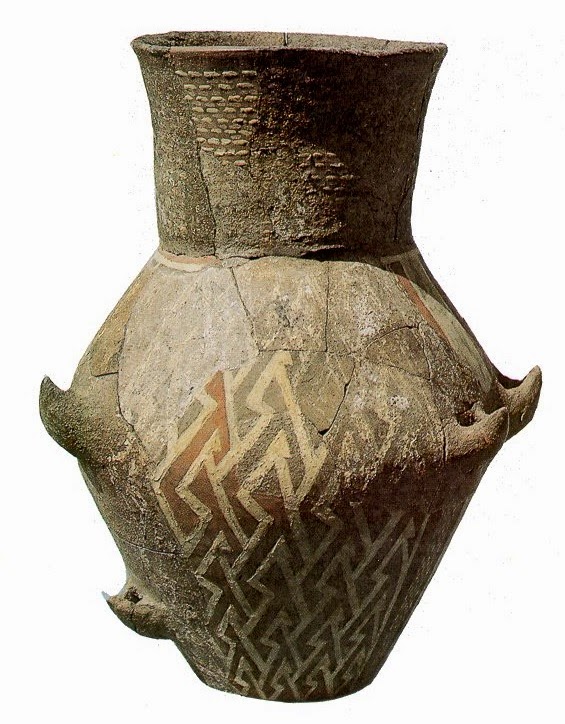

At the late Neolithic settlements of North-Holland, the analysis of the preserved food remains in the beakers provided clear evidence of acorns being pulverised and then cooked for consumption with the addition of fish fats and grain. The charred remains of acorn (Quercus), preserved at Zeewijk as fragmented cotyledons and isolated remains of cotyledon parenchyma, suggest that they were also processed at the site. No pericarp remains were found, suggesting that the acorns’ shells were peeled off prior to contact with fire. Charred acorn remains were also found at other Single Grave Culture sites in the region. [77]