Ór – Ireland’s Gold (Ór – Złoto Irlandii)

© by Goran Pavlovic © tłumaczenie Czesław Białczyński

Od razu zwróćmy uwagę na pochodzenie słowa oznaczającego złoto: Ór = OR, jak w SuOROżic / Su-AROżicz, SuOROg / Su-ARAg, gdzie Su-LOto = Z-ŁOto. (zgodnie z zasadą r →l → ł).

Ór – Ireland’s Gold

Ór – Złoto Irlandii

The earliest evidence for gold working dates to the fifth millennium BC. This is based on the discovery of the Varna cemetery which is located approximately half a kilometer from Lake Varna and 4 km from the Varna city centre in Bulgaria. The cemetery was dated to the period 4,600 BC to 4,200 BC. The cemetery belonged to the Charcolitic Varna culture. The graves of this cemetery were full of golden artifacts and they are considered to be the oldest golden artifacts in the world.

Najwcześniejsze dowody na obróbkę złota pochodzą z piątego tysiąclecia p.n.e. Opierają się na odkryciu cmentarza w Warnie, który znajduje się około pół kilometra od jeziora Warna i 4 km od centrum Warny w Bułgarii. Cmentarz datowano na okres od 4600 p.n.e. do 4200 p.n.e. Cmentarz należał do charkolitycznej kultury Warny. Groby na tym cmentarzu były pełne złotych artefaktów i są uważane za najstarsze złote artefakty na świecie.

These Varna guys were obsessed with gold. As a matter of fact, just one of the graves from the Varna cemetery, the so called golden grave (grave 43) contained more gold, than has been found in all the other archaeological sites in the world from that epoch…

Ci ludzie z Warny byli zafascynowani złotem. Rzeczywiście tylko jeden z grobów z cmentarza w Warnie, tak zwany złoty grób (grób 43), zawierał więcej złota, niż znaleziono we wszystkich innych stanowiskach archeologicznych na świecie z tej epoki…

It seems that this love of gold was not universal. The surrounding Balkan cultures like Vinca Culture seem not to care very much for gold and the situation was pretty much the same in the rest of Europe at that time.

Wygląda na to, że ta miłość do złota nie była powszechna. Okoliczne kultury bałkańskie, takie jak kultura Vinca, nie przepadają za złotem, a sytuacja w pozostałej części Europy w tamtym czasie była mniej więcej taka sama.

It took over a 1500 years for gold work to reach Britain and Ireland. The first gold objects appear in Ireland at the end of the third millennium (2200 BC). But it seems that once the Irish discovered gold, they became obsessed with it and couldn’t have enough of it. But it seems that the Irish had a very peculiar and exclusive taste when it came to the type of gold objects they liked. A few of these kind of thingies were found in the Early Bronze age archaeological site:

Minęło ponad 1500 lat, zanim wyroby ze złota dotarły do Brytanii i Irlandii. Pierwsze złote przedmioty pojawiły się w Irlandii pod koniec trzeciego tysiąclecia (2200 p.n.e.). Ale wydaje się, że gdy Irlandczycy odkryli złoto, stali się nim zafascynowani i nie mogli się nim nacieszyć. Ale wydaje się też, że Irlandczycy mieli bardzo osobliwy i ekskluzywny gust, jeśli chodzi o rodzaj złotych przedmiotów, które lubili. Kilka takich rzeczy znaleziono na stanowisku archeologicznym z wczesnej epoki brązu:

But it seems that the favorite type of golden trinkets of the late 3rd millennium Irish were these two types of gold objects: a peculiar gold lunulae and even more peculiar gold cross discs:

Wydaje się też, że ulubionym rodzajem złotych ozdób Irlandczyków z końca III tysiąclecia były te dwa rodzaje złotych przedmiotów: osobliwe złote lunule i jeszcze bardziej osobliwe złote dyski w kształcie krzyża:

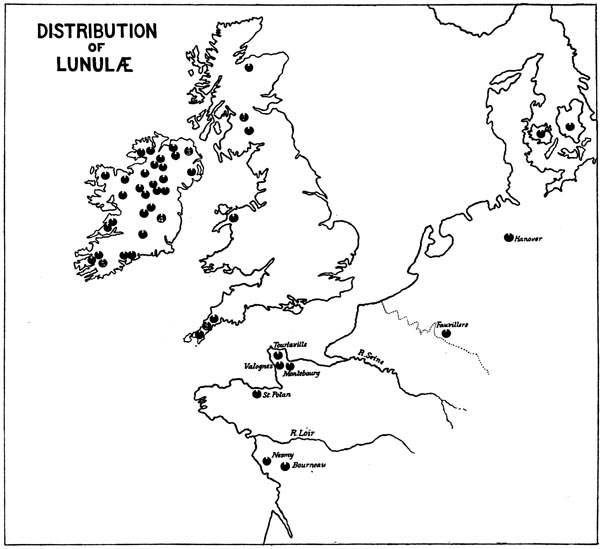

The Gold lunula (plural: lunulae) is a distinctive type of late Neolithic, Chalcolithic or (most often) early Bronze Age necklace or collar shaped like a crescent moon. Most have been found in Ireland, but there are moderate numbers in other parts of Europe as well, from Great Britain to areas of the continent fairly near the Atlantic coasts. Although no lunula has been directly dated, from associations with other artefacts it is thought they were being made sometime in the period between 2200–2000 BC. A wooden box associated with one Irish find has recently given a radiocarbon dating range of 2460–2040 BC.

Złota lunula (l. mnoga: lunule) to charakterystyczny rodzaj naszyjnika lub obroży z późnego neolitu, chalkolitu lub (najczęściej) wczesnej epoki brązu w kształcie półksiężyca. Większość z nich znaleziono w Irlandii, ale umiarkowana liczba znajduje się również w innych częściach Europy, od Wielkiej Brytanii po obszary kontynentu położone dość blisko wybrzeży Atlantyku. Chociaż nie datowano bezpośrednio żadnej lunuli, na podstawie powiązań z innymi artefaktami uważa się, że zostały wykonane w okresie między 2200 a 2000 rokiem p.n.e. Drewniana skrzynia związana z jednym z irlandzkich znalezisk niedawno dała zakres datowania radiowęglowego 2460–2040 rokiem p.n.e.

Beautiful things don’t you think? The Irish seem to think so too. Of the more than a hundred gold lunulae known from Western Europe, more than eighty were found in Ireland.

Piękne rzeczy, prawda? Irlandczycy również tak myślą. Z ponad stu złotych lunuli znanych z Europy Zachodniej, ponad osiemdziesiąt znaleziono w Irlandii.

Here some examples of European (Non Irish) gold lunulas and gold discs from „’Here comes the sun….’ solar symbolism in Early Bronze Age Ireland” by Mary Cahill.

Oto kilka przykładów europejskich (nie irlandzkich) złotych lunuli i złotych dysków z „’Here comes the sun…’ solar symbolism in Early Bronze Age Ireland” autorstwa Mary Cahill.

Lunula and a pair of gold discs from Cabeceiras de Basto, Portugal (© MuseuNacional de Arqueologia)

Lunula i para złotych dysków z Cabeceiras de Basto, Portugalia (© MuseuNacional de Arqueologia)

Pair of gold discs from Oviedo,Spain (© J. Camino Mayor, MuseoArqueológico de Asturias)

Para złotych dysków z Oviedo, Hiszpania (© J. Camino Mayor, MuseoArqueológico de Asturias)

This is what you can read on the National Museum of Ireland’s website about the 3rd millennium Bronze Age Irish gold craze:

Oto, co możesz przeczytać na stronie internetowej Narodowego Muzeum Irlandii o irlandzkim szaleństwie na punkcie złota w epoce brązu w III tysiącleciu:

The National Museum of Ireland’s collection of Bronze Age gold work is one of the largest and most important in western Europe. The immense quantity of Bronze Age gold from Ireland suggests that rich ore sources were known.

Kolekcja złotych dzieł z epoki brązu w Narodowym Muzeum Irlandii jest jedną z największych i najważniejszych w Europie Zachodniej. Ogromna ilość złota z epoki brązu z Irlandii sugeruje, że znane były bogate źródła rudy.

Gold has been found in Ireland at a number of locations, particularly in Co. Wicklow and Co. Tyrone. The gold is found in alluvial deposits from rivers and streams. This gold is weathered out from parent rock and can be recovered using simple techniques such as panning. These gold deposits are still exploited today.

This gold is weathered out from parent rock and can be recovered using simple techniques such as panning. In Wicklow mountains this technique is still used today by prospectors to find gold nuggets as you can see on the below picture and this video.

Złoto to jest wywietrzałe ze skały macierzystej i można je odzyskać za pomocą prostych technik, takich jak płukanie. W górach Wicklow technika ta jest nadal stosowana przez poszukiwaczy złota w celu znalezienia samorodków złota, jak widać na poniższym zdjęciu i tym filmie.

The Wicklow Mountains form the largest continuous upland area in Ireland. They occupy the whole centre of County Wicklow and stretch outside its borders into Counties Carlow, Wexford and Dublin. Where the mountains extend into County Dublin, they are known locally as the Dublin Mountains

Góry Wicklow tworzą największy ciągły obszar wyżynny w Irlandii. Zajmują całe centrum hrabstwa Wicklow i rozciągają się poza jego granice do hrabstw Carlow, Wexford i Dublin. Tam, gdzie góry rozciągają się na hrabstwo Dublin, są znane lokalnie jako Góry Dublin

Wicklow mountains are criss-crossed with thousands of streams and a lot of them carry gold and some of them carry a lot of gold.

Góry Wicklow są poprzecinane tysiącami strumieni, a wiele z nich niesie złoto, a niektóre z nich niosą dużo złota.

This is the Wicklow gold nugget (or more precisely its replica).

To jest bryłka złota z Wicklow (a dokładniej jej replika).

This gold nugget, weighing 682 grams is the biggest gold nugget found on British Isles. It was found in the Ballin valley stream which is located near the town of Avoca in County Wicklow, Ireland, in September 1795. A cast of the ‘Wicklow Nugget’ is held in the Natural History Museum in London. The stories of how the nugget was discovered are many. One story is it was found by workers felling trees on an estate owned by Lord Carysfort. Another that it was found by a local school teacher walking on the banks of what is now the Goldmines River. Either way the nugget sparked the first and only gold rush in Ireland. The search for the source of the gold that can still be panned today in the rivers of Wicklow has gone on since 1795 but the mother lode has never been found.

Ta bryłka złota, ważąca 682 gramy, jest największym samorodkiem złota znalezionym na Wyspach Brytyjskich. Znaleziono go we wrześniu 1795 roku w dolinie rzeki Ballin, niedaleko miasta Avoca w hrabstwie Wicklow w Irlandii. Odlew bryłki złota z Wicklow znajduje się w Muzeum Historii Naturalnej w Londynie. Istnieje wiele opowieści o tym, jak odkryto bryłkę. Jedna z nich mówi, że znaleźli ją robotnicy ścinający drzewa w posiadłości należącej do lorda Carysfort. Inna, że znalazł ją miejscowy nauczyciel szkolny, spacerując brzegiem rzeki Goldmines. Tak czy inaczej, bryłka złota zapoczątkowała pierwszą i jedyną gorączkę złota w Irlandii. Poszukiwania źródła złota, które do dziś można wypłukiwać w rzekach Wicklow, trwają od 1795 roku, ale żyła macierzysta nigdy nie została odkryta.

So there is plenty of gold in Ireland. But how did the Irish learn how to find it, exploit it and make these amazing gold artifacts from it? The National Museum of Ireland’s website say this:

While we do not know precisely how the late Neolithic people of Ireland became familiar with metalworking, it is clear that it was introduced as a fully developed technique. Essential metalworking skills must have been introduced by people already experienced at all levels of production, from ore identification and recovery through all stages of the manufacturing process….Basically the gold working had become well established in Ireland and Britain together with a highly productive copper and bronze working industry.

Chociaż nie wiemy dokładnie, w jaki sposób mieszkańcy późnego neolitu w Irlandii zapoznali się z obróbką metali, jasne jest, że została ona wprowadzona jako w pełni rozwinięta technika. Podstawowe umiejętności obróbki metali musiały zostać wprowadzone przez osoby już doświadczone na wszystkich etapach produkcji, od identyfikacji i odzyskiwania rudy po wszystkie etapy procesu produkcyjnego… Zasadniczo obróbka złota stała się dobrze ugruntowana w Irlandii i Wielkiej Brytanii wraz z wysoce produktywnym przemysłem obróbki miedzi i brązu.

What this basically says is that gold working was brought to Ireland by the outsiders, invaders, by the same people who brought copper mining and metallurgy. These guys arrived to Ireland between 2400 BC and 2200 BC looking for copper. And they found it. In huge quantities.

W zasadzie oznacza to, że obróbka złota została przywieziona do Irlandii przez przybyszów, najeźdźców, przez tych samych ludzi, którzy przywieźli wydobycie miedzi i metalurgię. Ci ludzie przybyli do Irlandii między 2400 p.n.e. a 2200 p.n.e. w poszukiwaniu miedzi. I ją znaleźli. W ogromnych ilościach.

Records of mining in Ireland date back to the Early Bronze Age when southwest Ireland was an important copper producer, with evidence of old copper workings at Ross Island located in Killarney, Co Kerry.

Zapisy górnictwa w Irlandii sięgają wczesnej epoki brązu, kiedy południowo-zachodnia Irlandia była ważnym producentem miedzi, z dowodami na stare wydobycie miedzi na wyspie Ross w Killarney, w hrabstwie Kerry.

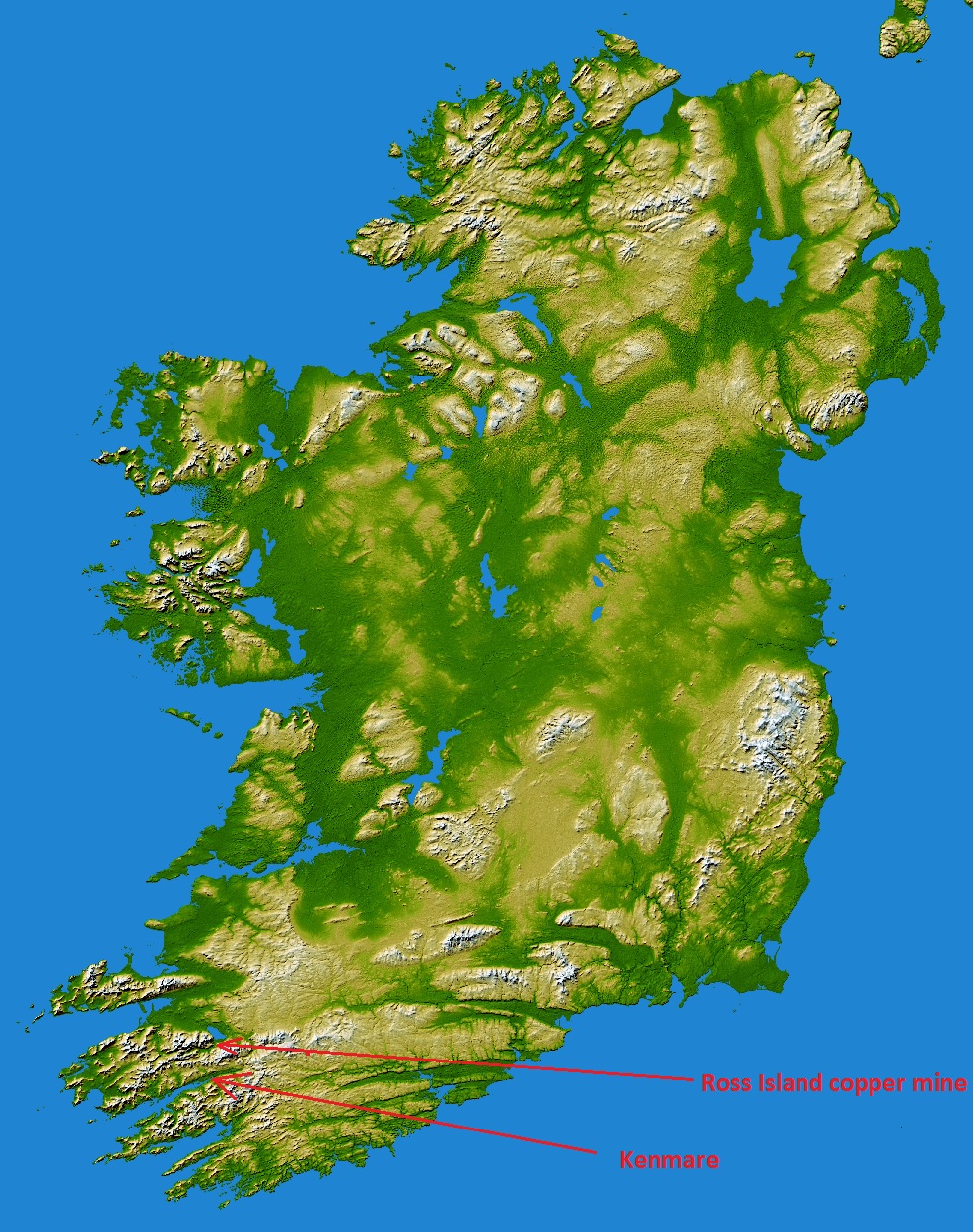

Ross Island is a claw-shaped peninsula in Killarney National Park, County Kerry. Copper extraction on the site is believed to be the source of the earliest known Irish Pre-Bronze Age metalwork, namely copper axe heads, halberds and knife/dagger blades dating from 2,400 – 2,200 BC. These finds have been distributed throughout Ireland and in the West of Britain – in South Britain the metalwork was imported from across the Channel.

Wyspa Ross to półwysep w kształcie pazura w Parku Narodowym Killarney, w hrabstwie Kerry. Uważa się, że wydobycie miedzi na tym terenie jest źródłem najwcześniejszych znanych irlandzkich wyrobów metalowych z okresu przed epoką brązu, a mianowicie miedzianych głowic toporów, halabard i ostrzy noży/sztyletów datowanych na 2400–2200 r. p.n.e. Znaleziska te były rozsiane po całej Irlandii i na zachodzie Brytanii — w południowej Brytanii wyroby metalowe były importowane zza kanału La Manche.

The archaeology of the site has unearthed both mining operations and a smelting camp where the Copper ore was processed into a type of metal distinctive enough to be traced these early tools. As there is no evidence that the complex technology had developed spontaneously, this early metallurgy would indicate contacts with mainland Europe – in particular, extending along the coastline from Spain through Normandy. The Ross island operation was associated with beaker pottery and continued until ca 1,900 BC

Archeologia na tym terenie odkryła zarówno operacje górnicze, jak i obóz hutniczy, w którym rudę miedzi przetwarzano na rodzaj metalu wystarczająco charakterystycznego, aby można było na nim prześledzić te wczesne narzędzia. Ponieważ nie ma dowodów na to, że złożona technologia rozwinęła się spontanicznie, ta wczesna metalurgia wskazywałaby na kontakty z kontynentalną Europą – w szczególności, rozciągającą się wzdłuż wybrzeża od Hiszpanii przez Normandię. Eksploatacja wyspy Ross była związana z ceramiką pucharową i trwała do ok. 1900 r. p.n.e.

And at the same time we see the appearance of the gold artifacts in Ireland too. So something very interesting happened between the 6th millennium BC and the 3rd millennium BC on the European Metal scene. As I already said the earliest evidence for gold working dates to the fifth millennium BC Varna culture. The earliest evidence for copper working dates to the 6th millennium Vinča culture. And as I said already, for a while the gold dudes from Varna and the copper and bronze dudes from Vinča didn’t really go out much and didn’t mix with one another or anyone else for that matter. They were too busy digging, smelting and making Metal, perfecting their art you know. But then one day, probably at the end of the 4th millennium, the beginning of the 3rd millennium, they must have been invited to a party organized by these new foreign kids who just came to Europe, from the steppe. I mean those steppe dudes were mixing some strong stuff in them pots they had, and their parties were the hottest thing in town. So I guess the Copper dudes kitted themselves out with all the copper tools and the Gold dudes kitted themselves out with all the gold bling and went to the party. What happened at that party is a bit hazy. But at some stage someone, and I would bet it was one of those steppe kids, said something like this: „Hey you, the copper dudes! Have you ever thought of making weapons out of copper?! I know the agricultural tools are useful but they are not cool man! You know what’s cool?! Daggers! And Axes! And you really have to start working on your image! You look too rough, too uncultivated, too like „Neolithic” or something! You need something like what those gold dudes are wearing! But you can’t just wear shit loads of gold bling and expect girls to say „He is so cool”! No, that just makes you look like a sissy! What you really want is shit loads of copper weapons and shit loads of gold bling! Then you gonna look like gangstas! Girls love gangstas man!” The rest is history. From that moment on, a once relatively peaceful Europe is overrun by a bunch of copper weapons wielding, beaker quaffing gangstas, covered in gold…

I w tym samym czasie widzimy pojawienie się złotych artefaktów również w Irlandii. Więc coś bardzo interesującego wydarzyło się między 6. tysiącleciem p.n.e. a 3. tysiącleciem p.n.e. na europejskiej scenie metalowej. Jak już powiedziałem, najwcześniejsze dowody obróbki złota pochodzą z kultury Varna z 5. tysiąclecia p.n.e. Najwcześniejsze dowody obróbki miedzi pochodzą z kultury Vinča z 6. tysiąclecia p.n.e. I jak już powiedziałem, przez jakiś czas faceci od złota z Varny i faceci od miedzi i brązu z Vinča nie wychodzili zbyt często i nie mieszali się ze sobą ani z nikim innym. Byli zbyt zajęci kopaniem, wytapianiem i wytwarzaniem metalu, udoskonalaniem swojej sztuki, wiesz. Ale pewnego dnia, prawdopodobnie pod koniec czwartego tysiąclecia, na początku trzeciego tysiąclecia, musieli zostać zaproszeni na imprezę zorganizowaną przez nowe dzieciaki z zagranicy, które dopiero co przybyły do Europy ze stepu. Mam na myśli, że ci goście ze stepu mieszali coś mocnego w swoich garnkach, a ich imprezy były najgorętszą rzeczą w mieście. Więc myślę, że goście z Copper wyposażyli się we wszystkie miedziane narzędzia, a goście z Gold wyposażyli się we wszystkie złote błyskotki i poszli na imprezę. To, co wydarzyło się na tej imprezie, jest trochę niejasne. Ale w pewnym momencie ktoś, a obstawiam, że to był jeden z tych dzieciaków ze stepu, powiedział coś takiego: „Hej wy, miedziani goście! Czy kiedykolwiek myśleliście o zrobieniu broni z miedzi?! Wiem, że narzędzia rolnicze są przydatne, ale nie są fajne, stary! Wiesz, co jest fajne?! Sztylety! I topory! I naprawdę musisz zacząć pracować nad swoim wizerunkiem! Wyglądasz zbyt surowo, zbyt nieokrzesanie, zbyt „neolitycznie” albo coś! Potrzebujesz czegoś takiego, co noszą ci złoci goście! Ale nie możesz po prostu nosić mnóstwa złotych błyskotek i oczekiwać, że dziewczyny powiedzą „On jest taki fajny”! Nie, to tylko sprawia, że wyglądasz jak mięczak! Tak naprawdę chcesz mnóstwa miedzianej broni i mnóstwa złotych błyskotek! Wtedy będziesz wyglądał jak gangster! Dziewczyny kochają gangsterów, stary!” Reszta to już historia. Od tego momentu, niegdyś stosunkowo spokojna Europa zostaje opanowana przez bandę gangsterów władających miedzianą bronią, pijących zlewki, pokrytych złotem…

The guys who jumped out of the boat on the Irish shore in the late 3rd millennium BC were one of those guys. But these were no sissies, a peace loving people who kept themselves to themselves. They came to Ireland to mine and process copper to make weapons and I am sure they knew how to use them. It is very possible that they very quickly make themselves the only gang in town. O and these gangstas loved gold. So they, employed the same mining and metallurgical skills they used to find, mine and process Irish copper to find and process Irish gold and turn it into gold lunulae and gold cross discs that they loved so much. Right? Not exactly.

Faceci, którzy wyskoczyli z łodzi na irlandzkim brzegu pod koniec III tysiąclecia p.n.e. byli jednymi z nich. Ale to nie byli mięczaki, kochający pokój ludzie, którzy trzymali się z dala od siebie. Przybyli do Irlandii, aby wydobywać i przetwarzać miedź, aby wytwarzać broń i jestem pewien, że wiedzieli, jak jej używać. Jest bardzo prawdopodobne, że bardzo szybko stali się jedynym gangiem w mieście. O i ci gangsterzy kochali złoto. Więc wykorzystali te same umiejętności górnicze i metalurgiczne, których użyli do znalezienia, wydobycia i przetworzenia irlandzkiej miedzi, aby znaleźć i przetworzyć irlandzkie złoto i zamienić je w złote lunulae i złote krzyże, które tak bardzo kochali. Tak? Niezupełnie.

Back to the National Museum of Ireland’s website then goes on to say this:

Powrót do Narodowego Muzeum Irlandii gdzie strona internetowa następnie mówi to:

The National Museum of Ireland’s website is basically saying that even though the Early Bronze Age Irish were heavily blinged, we have no idea where the gold used to make this bling came from. Well, it seems that the information on the National Museum of Ireland’s website is slightly out of date. We actually now know where the gold used to make the early Bronze Age Irish bling came from, and it didn’t come from Ireland. This is the result of the latest study conducted by the scientists from the Bristol university who recently, together with the scientists from Leeds university, compared the gold from which the early Irish gold artifacts were made, with the naturally occurring gold deposits in the British Isles. The results were published in the paper entitled: „The genesis of gold mineralisation hosted by orogenic belts: A lead isotope investigation of Irish gold deposits„. You can also find them in the paper entitled „A Non-local Source of Irish Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age Gold„.

Strona internetowa Narodowego Muzeum Irlandii zasadniczo mówi, że chociaż Irlandczycy z wczesnej epoki brązu byli mocno błyszczeni, nie mamy pojęcia, skąd pochodziło złoto używane do robienia tego błyszczenia. Cóż, wydaje się, że informacje na stronie internetowej Narodowego Muzeum Irlandii są nieco nieaktualne. Właściwie wiemy teraz, skąd pochodziło złoto używane do robienia irlandzkiego błyszczenia z wczesnej epoki brązu, i nie pochodziło ono z Irlandii. To wynik najnowszych badań przeprowadzonych przez naukowców z uniwersytetu w Bristolu, którzy niedawno, wspólnie z naukowcami z uniwersytetu w Leeds, porównali złoto, z którego wykonano wczesne irlandzkie złote artefakty, z naturalnie występującymi złożami złota na Wyspach Brytyjskich. Wyniki opublikowano w artykule zatytułowanym: „Geneza mineralizacji złota w pasach orogenicznych: badanie izotopów ołowiu w irlandzkich złożach złota”. Można je również znaleźć w artykule zatytułowanym „Nielokalne źródło irlandzkiego złota chalkolitycznego i wczesnej epoki brązu”.

Chris Standish, an archaeology PhD student in Bristol University used the latest advances in geochemistry to compare Irish native gold and museum gold using variations in the four natural types of lead atoms, or lead isotopes. The quantities of lead are tiny, around 0.002 per cent, and were measured using a mass spectrometer. The chemical composition of the material used to make the early Bronze Age, 2,200 to 1,800 BC gold artifacts was cross checked and proved to be consistent. This suggests that all the early Bronze Age Irish gold have come from one area, possibly from river gravels. This chemical composition was then compared with the composition of all known Irish natural gold deposits. The chemical composition of the naturally occurring gold in Ireland was collected by the geologist Rob Chapman from Leeds University, who has spent hours standing in ice-cold streams and rivers across Ireland panning for gold.

Chris Standish, doktorant archeologii na uniwersytecie w Bristolu, wykorzystał najnowsze osiągnięcia w geochemii, aby porównać rodzime irlandzkie złoto i złoto muzealne, wykorzystując różnice w czterech naturalnych typach atomów ołowiu, czyli izotopach ołowiu. Ilości ołowiu są niewielkie, wynoszą około 0,002 procent i zostały zmierzone za pomocą spektrometru masowego. Skład chemiczny materiału użytego do wykonania złotych artefaktów z wczesnej epoki brązu, 2200–1800 p.n.e., został sprawdzony krzyżowo i okazał się spójny. Sugeruje to, że całe irlandzkie złoto z wczesnej epoki brązu pochodziło z jednego obszaru, prawdopodobnie z żwirów rzecznych. Następnie porównano ten skład chemiczny ze składem wszystkich znanych irlandzkich naturalnych złóż złota. Skład chemiczny naturalnie występującego złota w Irlandii został zebrany przez geologa Roba Chapmana z Uniwersytetu w Leeds, który spędził godziny stojąc w lodowatych strumieniach i rzekach w całej Irlandii, szukając złota.

Scientists couldn’t find a match between any of the Irish gold deposits and the Museum gold. They examined likely areas, including the gold deposits from Mournes, Croagh Patrick, Counties Wicklow, Wexford and Waterford. Looking purely at the lead isotopes, gold in the artifacts is most consistent with gold from the southeast (Wicklow). But there is too little silver and trace metal for it to be a proper match. Standish suggests there may be gold he has yet to analyse, but another, controversial, explanation is gold imports. According to Chapman, “The lead signature he [Standish] gained from the early Bronze Age artifacts corresponded to the granite rocks in Cornwall”. This means that the Early Bronze Age Irish gold artifacts were made from gold found and panned in Cornwall.

Naukowcy nie mogli znaleźć żadnego z irlandzkich złóż złota i złota z muzeum. Zbadali prawdopodobne obszary, w tym złoża złota z Mournes, Croagh Patrick, hrabstw Wicklow, Wexford i Waterford. Patrząc wyłącznie na izotopy ołowiu, złoto w artefaktach jest najbardziej zgodne ze złotem z południowego wschodu (Wicklow). Ale jest zbyt mało srebra i śladowych metali, aby można było to właściwie dopasować. Standish sugeruje, że może być złoto, którego jeszcze nie przeanalizował, ale innym, kontrowersyjnym wyjaśnieniem jest import złota. Według Chapmana „główny podpis, który [Standish] uzyskał z artefaktów z wczesnej epoki brązu, odpowiadał granitowym skałom w Kornwalii”. Oznacza to, że irlandzkie złote artefakty z wczesnej epoki brązu zostały wykonane ze złota znalezionego i wypłukanego w Kornwalii.

This is a golden lunula from Cornwall dated to the period 2400BC-2000BC. Does it predate the Irish ones?

To złota lunula z Kornwalii datowana na okres 2400 p.n.e.-2000 p.n.e. Czy jest starsza od irlandzkich?

Chapman then went to say that the results of the study „have irritated some archaeologists„.

Następnie Chapman stwierdził, że wyniki badania „zirytowały niektórych archeologów”.

So Chapman then had to add this to his paper: “Natural gold does occur in Cornwall, but it is difficult to find and we cannot say categorically whether the gold content is compatible or not. Since the early Bronze Age, the land has changed so much that you cannot visit the same sites available to the Bronze Age people; some lie underwater. One possibility is that there is a deposit of gold somewhere in Ireland which has eluded modern prospectors but was used by Bronze Age people….”

Więc Chapman musiał dodać to do swojego artykułu: „Naturalne złoto występuje w Kornwalii, ale trudno je znaleźć i nie możemy kategorycznie stwierdzić, czy zawartość złota jest zgodna, czy nie.Od wczesnej epoki brązu ziemia zmieniła się tak bardzo, że nie można odwiedzić tych samych stanowisk, które były dostępne dla ludzi z epoki brązu; niektóre leżą pod wodą.Jedną z możliwości jest to, że gdzieś w Irlandii znajduje się złoże złota, które umknęło współczesnym poszukiwaczom, ale było używane przez ludzi epoki brązu…”

Given extensive gold exploration in Ireland since the 1980s, a hidden source is somewhat unlikely, say geologists, dimming hopes of an Irish El Dorado. But it’s a possibility. And archaeologists and historians, who were irritated by the results of this study and who are refusing to accept the new geological data are clinging to it.

One of those irritated archaeologists is Mary Cahill, curator of the National Museum of Ireland’s Bronze Age collection, who had this to say about the whole thing: „…there is no supporting archaeological evidence for extensive gold imports to Ireland at this time. We know that Irish copper and bronze objects turn up in Britain, but there are no signs of gold coming in. And clues pointing to southern Britain as a source for Irish gold are not conclusive….„. This is a perfect example of how archaeologists and historians are refusing to accept the latest scientific data because it contradicts with commonly accepted theories of what happened.

Jedną z tych zirytowanych archeologów jest Mary Cahill, kuratorka kolekcji epoki brązu w Narodowym Muzeum Irlandii, która miała do powiedzenia na ten temat: „…nie ma żadnych dowodów archeologicznych potwierdzających rozległe importy złota do Irlandii w tym czasie. Wiemy, że irlandzkie przedmioty z miedzi i brązu pojawiają się w Wielkiej Brytanii, ale nie ma żadnych oznak napływu złota. A wskazówki wskazujące na południową Brytanię jako źródło irlandzkiego złota nie są rozstrzygające…”. To doskonały przykład tego, jak archeolodzy i historycy odmawiają zaakceptowania najnowszych danych naukowych, ponieważ są one sprzeczne z powszechnie akceptowanymi teoriami na temat tego, co się wydarzyło.

I also love the way these finds were actually interpreted by Standish:

Uwielbiam też to, że te znaleziska były prawdziwe i tak interpretowane przez Standisha:

Lead author Dr Chris Standish says: “This is an unexpected and particularly interesting result as it suggests that Bronze Age gold workers in Ireland were making artefacts out of material sourced from outside of the country, despite the existence of a number of easily-accessible and rich gold deposits found locally.

Główny autor dr Chris Standish mówi: „To nieoczekiwany i szczególnie interesujący wynik, ponieważ sugeruje, że złotnicy z epoki brązu w Irlandii wytwarzali artefakty z materiałów pochodzących spoza kraju, pomimo istnienia wielu łatwo dostępnych i bogatych złóż złota znalezionych lokalnie.

“It is unlikely that knowledge of how to extract gold didn’t exist in Ireland, as we see large scale exploitation of other metals. It is more probable that an ‘exotic’ origin was cherished as a key property of gold and was an important reason behind why it was imported for production.”

„Jest mało prawdopodobne, aby wiedza o tym, jak wydobywać złoto, nie istniała w Irlandii, ponieważ widzimy eksploatację innych metali na dużą skalę. Bardziej prawdopodobne jest, że „egzotyczne” pochodzenie było cenione jako kluczowa właściwość złota i stanowiło ważny powód, dla którego było ono importowane do produkcji”.

Isn’t a much simpler and more logical explanation that the Early Bronze Age gold objects found in Ireland were made in the same place where the gold was found, in Cornwall and that they were then brought to Ireland as finished products? But that would make even more people even more irritated. This would effectively put an end to the accepted history and the story of the Early Bronze Age Ireland being the Golden Isle, the center of the European gold working crafts of that time …So the official archaeology and history is surprised and irritated with the new data showing that the „Irish gold” was brought to Ireland.

Czyż nie jest o wiele prostszym i bardziej logicznym wyjaśnieniem, że złote przedmioty z wczesnej epoki brązu znalezione w Irlandii zostały wykonane w tym samym miejscu, w którym znaleziono złoto, w Kornwalii, i że zostały następnie przywiezione do Irlandii jako gotowe produkty? Ale to jeszcze bardziej rozdrażniłoby jeszcze więcej osób. To skutecznie położyłoby kres powszechnie akceptowanej historii i opowieści o Irlandii z wczesnej epoki brązu jako Złotej Wyspie, centrum europejskiego rzemiosła złotniczego tamtych czasów… Tak więc oficjalna archeologia i historia są zaskoczone i zirytowane nowymi danymi pokazującymi, że „irlandzkie złoto” zostało przywiezione do Irlandii.

But guess what? The old Irish annals, the so called „pseudo history” tells us that the gold was „brought into Ireland” and that it was brought right about the time when the first gold artifacts start appearing in Ireland.

Ale zgadnijcie co? Stare irlandzkie annały, tak zwana „pseudohistoria”, mówią nam, że złoto zostało „przywiezione do Irlandii” i że zostało przywiezione mniej więcej w czasie, gdy pierwsze złote artefakty zaczęły pojawiać się w Irlandii.

The old Irish annals tell us that the first race that lived in Ireland were Fomorians. Then, after the flood, came the people of Partholón who are credited with introducing cattle husbandry, plowing, cooking, dwellings, trade, and dividing the island in four. But Partholon also brought gold.

Stare irlandzkie annały mówią nam, że pierwszą rasą, która żyła w Irlandii, byli Fomorianie. Następnie, po potopie, przybyli ludzie z Partholón, którym przypisuje się wprowadzenie hodowli bydła, orki, gotowania, mieszkań, handlu i podziału wyspy na cztery. Ale Partholon przywiózł również złoto.

Labor Gabala Erenn mówi nam, że Partholon miał ze sobą dwóch kupców: Biobhala (Bibala) i Beabhala (Babala). Babal przywiózł bydło do Irlandii, a Bibal przywiózł złoto.

So when did Partholon come to Ireland?

Kiedy więc Partholon przybył do Irlandii?

The Annals of the Four Masters says they arrived in 2520 Anno Mundi (after the „creation of the world”), Seathrún Céitinn’s Foras Feasa ar Érinn says they arrived in 2061 BC, Annals of Four Masters says that they arrived at 2680 BC. So Sometimes in the second half of the 3rd millennium.

Roczniki Czterech Mistrzów podają, że przybyli w 2520 Anno Mundi (po „stworzeniu świata”), Foras Feasa ar Érinn Seathrúna Céitinna podaje, że przybyli w 2061 r. p.n.e., Roczniki Czterech Mistrzów podają, że przybyli w 2680 r. p.n.e. Czasami więc w drugiej połowie III tysiąclecia.

So far the „pseudo history” is right on the money.

Jak dotąd „pseudohistoria” jest prawidłowa.

And finally where did the Parthalon come from?

I wreszcie, skąd wziął się Parthalon?

The earliest surviving reference to the Partholóin is in the Historia Brittonum, a 9th-century British Latin compilation attributed to one Nennius. Here, „Partholomus” is said to have come to Ireland from Spain.

Najwcześniejsze zachowane odniesienie do Partholóin znajduje się w Historia Brittonum, IX-wiecznej brytyjskiej kompilacji łacińskiej przypisywanej pewnemu Nenniuszowi. Tutaj „Partholomus” ma przybyć do Irlandii z Hiszpanii.

Seathrún Céitinn’s 17th century compilation Foras Feasa ar Érinn, says that Partholón was the son of Sera, the king of Greece, and fled his homeland after murdering his father and mother. He lost his left eye in the attack on his parents. He and his followers set off from Greece, sailed via Sicily, around Iberia, and arrived in Ireland from the west, having traveled for seven years.

XVII-wieczna kompilacja Seathrúna Céitina Foras Feasa ar Érinn mówi, że Partholón był synem Sery, króla Grecji, i uciekł z ojczyzny po zamordowaniu ojca i matki. Stracił lewe oko w ataku na rodziców. On i jego zwolennicy wyruszyli z Grecji, popłynęli przez Sycylię, wokół Półwyspu Iberyjskiego i przybyli do Irlandii z zachodu, podróżując przez siedem lat.

The Lebor Gabála Érenn, an 11th-century Christian pseudo-history of Ireland, tells us more. It tells us that Partholón came from either Sicily or Mygdonia which was an ancient territory, part of Ancient Thrace. According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn Partholon was the son of Sera, son of Sru, a descendant of Magog, son of Japheth (see Japhetites), son of Noah. Partholón and his people sail to Ireland via Gothia, Anatolia, Greece, Sicily and Iberia, and landing at Inber Scéne (Kenmare in County Kerry). This is the closest landing point next to the ancient Ross Island copper mine. This mine was the reason why the pot loving, copper weapons making and gold bling wearing Beaker gangstas came to Ireland.

Lebor Gabála Érenn, XI-wieczna chrześcijańska pseudohistoria Irlandii, mówi nam więcej. Mówi nam, że Partholón pochodził albo z Sycylii, albo z Mygdonii, która była starożytnym terytorium, częścią starożytnej Tracji. Według Lebor Gabála Érenn Partholon był synem Sery, syna Sru, potomka Magoga, syna Jafeta (patrz Jafetyci), syna Noego. Partholón i jego ludzie płyną do Irlandii przez Gothię, Anatolię, Grecję, Sycylię i Iberię, lądując w Inber Scéne (Kenmare w hrabstwie Kerry). To najbliższe miejsce lądowania obok starożytnej kopalni miedzi na wyspie Ross. Kopalnia ta była powodem, dla którego gangsterzy kochający garnki, wytwarzający miedzianą broń i noszący złote błyskotki, przybyli do Irlandii.

So is the Irish „pseudo history” right about the Balkans being the birth place of Partholon like it was about when he landed in Ireland, where he landed in Ireland and the fact that he and his people had brought gold to Ireland? I believe so. But I will talk about this in one of my next posts.

Czy zatem irlandzka „pseudohistoria” ma rację co do Bałkanów jako miejsca narodzin Partholona, tak jak to było w przypadku, gdy wylądował w Irlandii, gdzie wylądował w Irlandii i faktu, że on i jego ludzie przywieźli złoto do Irlandii? Myślę, że tak. Ale o tym opowiem w jednym z moich następnych postów.

źródło: https://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2015/07/or-irelands-gold.html