How did oaks repopulate Europe? (Jak dęby ponownie zaludniły Europę?)

© by Goran Pavlivic © tłumaczenie by Czesław Bialczyński

In my post about oaks I talked about the oak tree and how useful this tree was and still is to people. In this post I would like to explain why I believe that people were as useful to the oak trees as the oak trees were useful to people. I believe that the influence that people had on the distribution of oaks in Europe could have been far greater then it is currently accepted. I think that the northward spreading of oaks from their glacial refugiums after the last ice age was actually the result of the northward spreading of humans from the same refugiums. I believe that it was humans who brought the oaks to the north of Europe. Let me explain why I believe that that was the case.

W moim poście o dębach mówiłem o dębie i o tym, jak przydatne było i nadal jest to drzewo dla ludzi. W tym poście chciałbym wyjaśnić, dlaczego uważam, że ludzie byli tak samo przydatni dębom, jak dęby były przydatne ludziom. Uważam, że wpływ, jaki mieli ludzie na rozmieszczenie dębów w Europie, mógł być znacznie większy niż się to obecnie przyjmuje. Myślę, że rozprzestrzenianie się dębów na północ z ich lodowcowych refugium po ostatniej epoce lodowcowej było w rzeczywistości wynikiem rozprzestrzeniania się na północ ludzi z tych samych refugium. Uważam, że to ludzie sprowadzili dęby na północ Europy. Pozwólcie, że wyjaśnię, dlaczego uważam, że tak było.

As I said in my last post, fossil pollen evidence in Europe indicates that during the last Glacial Maximum (20 000 years ago), oak species were confined to three main Pleistocene refugiums in southern Europe: Iberia, Italy and the Balkans. Then around 17,000 BC, the global temperature started to increase which resulted in melting of the great Northern Hemisphere ice sheets. This melt down lasted until about 4,000 BC, and the result was a global warming and the increase in sea levels. But this increase in temperature, warming and sea level increase was not uniform. If we look at the global sea levels, we see that during the period of the big melt down, 17,000 BC to about 4,000 BC, they rose by a total of more than 120 meters. This means that if the temperature increase was uniform, the average rate of sea-level rise would have been roughly 1 meter per century. However, when we look at the actual sea level rise figures, we see that the gradual sea level rise at an average rate of 1 meter per century was interrupted by two periods with rates of rise up to 2.5 meters per century, during period 13 000 – 11 000 BC, and period 11 000 – 9 000 BC. The first of these jumps in the amount of ice-sheet melt water entering the world ocean coincides with the beginning of a period of global climate warming called the Bølling-Allerød period. The Bølling-Allerød period was a warm and moist period that occurred during the final stages of the last glacial period. This warm period began around 12,700 BC and ended abruptly around to 10,700 BC. This is the beginning of the cold period called Younger Dryas, also known as „the big freeze”. This cold period is thought to have been caused by the collapse of the North American ice sheets. The temperatures in the North Hemisphere were reduced back to near-glacial levels within a decade. Younger Dryas lasted between 10,800 and 9500 BC, when we see the second big jump in temperature and resulting sea level rise rate.

Jak powiedziałem w moim ostatnim poście, skamieniałe dowody pyłkowe w Europie wskazują, że podczas ostatniego maksimum lodowcowego (20 000 lat temu) gatunki dębów były ograniczone do trzech głównych ostoi plejstoceńskich w południowej Europie: Iberia, Włochy i Bałkany. Następnie około 17 000 lat pne globalna temperatura zaczęła rosnąć, co spowodowało topnienie wielkich pokryw lodowych na półkuli północnej. To topnienie trwało do około 4000 lat pne, a rezultatem było globalne ocieplenie i wzrost poziomu mórz. Ale ten wzrost temperatury, ocieplenia i wzrost poziomu mórz nie był równomierny. Jeśli spojrzymy na globalne poziomy mórz, zobaczymy, że w okresie wielkiego topnienia, od 17 000 pne do około 4000 pne, podniosły się one łącznie o ponad 120 metrów. Oznacza to, że gdyby wzrost temperatury był równomierny, średnie tempo wzrostu poziomu mórz wyniosłoby około 1 metra na stulecie. Kiedy jednak spojrzymy na rzeczywiste dane dotyczące podnoszenia się poziomu mórz, zobaczymy, że stopniowe podnoszenie się poziomu mórz w średnim tempie 1 metra na stulecie zostało przerwane przez dwa okresy o tempie wzrostu do 2,5 metra na stulecie, w okresie 13 000 – 11 000 pne i okres 11 000 – 9 000 pne. Pierwszy z tych skoków ilości wody ze stopionego lodu wpływającej do światowego oceanu zbiega się z początkiem okresu globalnego ocieplenia klimatu zwanego okresem Bølling-Allerød. Okres Bølling-Allerød był ciepłym i wilgotnym okresem, który miał miejsce podczas końcowych etapów ostatniego zlodowacenia. Ten ciepły okres rozpoczął się około 12 700 pne i zakończył się nagle około 10 700 pne. To początek zimnego okresu zwanego młodszym dryasem, zwanego też „wielkim mrozem”. Uważa się, że ten zimny okres był spowodowany upadkiem pokryw lodowych w Ameryce Północnej. Temperatury na półkuli północnej zostały zredukowane z powrotem do poziomu bliskiego lodowcowi w ciągu dekady. Młodszy Dryas trwał od 10 800 do 9500 pne, kiedy obserwujemy drugi duży skok temperatury i wynikający z niego wzrost poziomu mórz.

During Younger Dryas period, most of Eurasia and North America had been covered by tundra with swaths of taiga.The tundra biome is the coldest of all the biomes. Tundra comes from the Finnish word „tunturi”, meaning treeless plain. It is noted for its frost-molded landscapes, extremely low temperatures, little precipitation, poor nutrients, and short growing seasons.

W okresie młodszego dryasu większość Eurazji i Ameryki Północnej była pokryta tundrą z połaciami tajgi. Biom tundry jest najzimniejszym ze wszystkich biomów. Tundra pochodzi od fińskiego słowa „tunturi”, oznaczającego bezdrzewną równinę. Jest znana ze swoich ukształtowanych przez mróz krajobrazów, ekstremalnie niskich temperatur, niewielkich opadów, ubogich składników odżywczych i krótkich sezonów wegetacyjnych.

Taiga is a high latitude northern hemisphere biome consisting mostly of conifer (fir) and birch forest. Temperature regimes within some of the taiga areas are among the lowest on Earth, since there is a continental aspect to the interior portions of the taiga, making it colder than many locations in the polar desert to the north. Extreme minimums in the taiga are typically lower than those of the tundra.

Tajga to biom na półkuli północnej położony na dużych szerokościach geograficznych, składający się głównie z lasów iglastych (jodłowych) i brzozowych. Reżimy temperatur w niektórych obszarach tajgi należą do najniższych na Ziemi, ponieważ wewnętrzne części tajgi mają aspekt kontynentalny, co sprawia, że jest chłodniej niż w wielu miejscach na pustyni polarnej na północy. Ekstremalne minima w tajdze są zazwyczaj niższe niż w tundrze.

So this is what most of the north of Europe was like during the Younger Drias.

Younger Drias was succedded by the Preboreal stage of the Holocene epoch. Preboreal stage lasted from 8,300 to 7,000 BC. It is the first stage of the Holocene epoch. The Preboreal started with an abrubt climate change which resulted in rapid rise of the global temperature and rapid rise of sea waters.

Młodszy Drias został zastąpiony przez etap przedborealny epoki holocenu. Faza przedborealna trwała od 8300 do 7000 pne. Jest to pierwszy etap epoki holocenu. Preboreal rozpoczął się od gwałtownej zmiany klimatu, która spowodowała gwałtowny wzrost temperatury na świecie i gwałtowny wzrost poziomu wód morskich.

During the Preboreal period, large quantities of tree pollen began to replace the pollen of open-land species, as the most mobile and flexible arboreal (tree) species colonised their way northward, replacing the ice-age tundra plants. Foremost among them were the birches, accompanied by rowan also known as mountain-ash (known as jasen in Serbian) and aspen (known as jasika in Serbian).

W okresie preborealnym duże ilości pyłku drzew zaczęły zastępować pyłki gatunków występujących na terenach otwartych, ponieważ najbardziej mobilne i elastyczne gatunki nadrzewne (drzewa) skolonizowały swoją drogę na północ, zastępując rośliny tundry z epoki lodowcowej. Dominowały wśród nich brzozy, którym towarzyszyła jarzębina zwana też gorskim jarząbem (po serbsku jasen) i osika (po serbsku jasika).

This is a rowan tree:

To jest jarzębina

This is an aspen tree:

To jest osika

Especially sensitive to temperature changes and moving northward almost immediately were the dwarf and shrub juniper (known as kleka in Serbian) respectively, which reached a maximum density in the Preboreal, before their niches were shaded out. This is a juniper bush:

Szczególnie wrażliwe na zmiany temperatury i niemal natychmiast przemieszczające się na północ były odpowiednio jałowiec karłowaty i krzewiasty (znany jako kleka po serbsku), które osiągnęły maksymalne zagęszczenie w okresie preborealnym, zanim ich nisze zostały zacienione. To jest krzak jałowca:

Pine soon followed, for which reason the resulting open woodland is often called a birch or a pine-birch forest:

Wkrótce pojawiła się sosna, z tego powodu powstały otwarty las jest często nazywany brzeziną lub lasem sosnowo-brzozowym:

In the yet warmer early Boreal period (7000 – 5500 BC) hazel and pine expanded into the birch woodlands to such a degree that palynologists refer to the resulting ecology as the hazel-pine forest. I am not sure exactly what these forests used to look like because they don’t exist any more, but maybe they looked something like this. This is old hazel forest from Britain:

In the late Boreal it was supplanted by the spread of a deciduous forest called the mixed-oak forest. Pine, birch and hazel were reduced in favour of oaks, elm, lime (linden) and alder. The former tundra was now closed by a canopy of dense forest.

W późnym borealu został wyparty przez rozprzestrzenianie się lasu liściastego zwanego dąbrową mieszaną. Zredukowano sosnę, brzozę i leszczynę na rzecz dębu, wiązu, lipy (lipy) i olchy. Dawna tundra była teraz zamknięta baldachimem gęstego lasu.

Those interested in climatic and vegetative conditions in Europe over the last 150,000 years will find this web page quite interesting.

Osoby zainteresowane warunkami klimatycznymi i wegetatywnymi w Europie na przestrzeni ostatnich 150 000 lat uznają tę stronę za bardzo interesującą.

It is currently accepted that oak started to emerge from refugiums in southern Europe as the ice caps began to retreat at the end of the Younger Drias around 9500 BC. Oaks arrived in North Central Europe by the 8500 BC and to Eastern Britain by 7500 BC.

Obecnie przyjmuje się, że dąb zaczął wyłaniać się z ostoi w południowej Europie, gdy czapy lodowe zaczęły się cofać pod koniec młodszego driasu około 9500 pne. Dąb przybył do północno-środkowej Europy około 8500 pne, a do wschodniej Wielkiej Brytanii około 7500 pne.

But how did the oak forests expand from the southern Europe into Central Europe and Northern Europe?

Ale w jaki sposób lasy dębowe rozszerzyły się z południowej Europy do Europy Środkowej i Północnej?

How do forests expand? A tree grows out of a seed. This seed falls from the tree branch on the ground and if it falls onto a fertile soil it sprouts into another tree. If the seed falls straight down from the branch the next tree generation will sprout at the distance of the furthest branch reach from the tree trunk, which is maximum 36 meters.

Jak powiększają się lasy? Drzewo wyrasta z nasionka. To ziarno spada z gałęzi drzewa na ziemię, a jeśli spadnie na żyzną glebę, kiełkuje w inne drzewo. Jeśli ziarno spadnie z gałęzi prosto w dół, kolejne pokolenie drzew wykiełkuje w odległości najdalszej gałęzi od pnia drzewa, czyli maksymalnie 36 metrów.

If the seed is light and can be carried by wind, and is falling from a big height during a strong wind, it can be carried away maybe up to the maximum tree height distance from the trunk, which could be up to a 120 meters and maybe even more.

Jeśli ziarno jest lekkie i może być przenoszone przez wiatr, a przy silnym wietrze spada z dużej wysokości, może zostać przeniesione na maksymalną odległość drzewa od pnia, która może wynosić nawet 120 metrów a może nawet więcej.

If the tree grows near water and produces fruit or seed which can float on water then the seed can end up anywhere down stream from the tree. If the tree produces fruit which has tiny indigestible seeds, and if the fruit is eaten whole by birds or animals or humans, then the seed can be spread far and wide and deposited during defecation.

Jeśli drzewo rośnie w pobliżu wody i wydaje owoce lub nasiona, które mogą unosić się na wodzie, wówczas nasiona mogą znaleźć się w dowolnym miejscu w dół strumienia od drzewa. Jeśli drzewo wydaje owoce, które mają maleńkie niestrawne nasiona i jeśli owoce są zjadane w całości przez ptaki, zwierzęta lub ludzi, wówczas nasiona mogą być rozsiewane daleko i osadzane podczas wypróżniania.

Knowing all this we can understand why biologists believe that forests expand in general at a pace between 250-500 meters per year.

Wiedząc to wszystko, możemy zrozumieć, dlaczego biolodzy uważają, że lasy generalnie powiększają się w tempie 250-500 metrów rocznie.

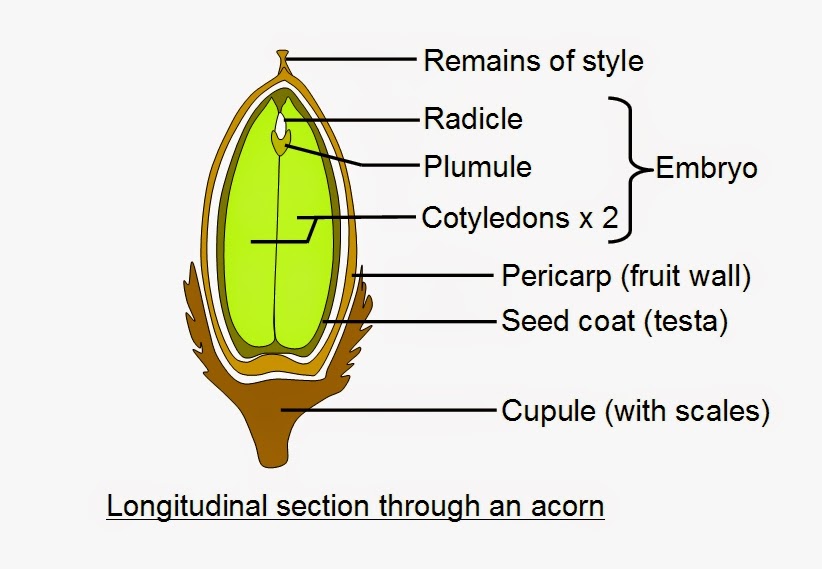

But I believe that the above estimate does not apply to oaks. Oak seed is acorn, and acorns are among some of the heaviest tree seeds in northern hemisphere. So oak seeds can’t be carried away very far by the wind so the maximum acorn fall distance from the tree trunk is not more than few meters from the edge of the tree crown. This means that the next generation of oaks sprouting from the fallen acorns will sprout at maximum 40 meters from the parent tree. Oak produces edible seeds, acorns, which are encased in a protective hard shell.

Uważam jednak, że powyższe oszacowanie nie dotyczy dębów. Nasiona dębu to żołędzie, a żołędzie należą do najcięższych nasion drzew na półkuli północnej. Tak więc nasiona dębu nie mogą być przenoszone przez wiatr na duże odległości, więc maksymalna odległość opadania żołędzi od pnia wynosi nie więcej niż kilka metrów od krawędzi korony drzewa. Oznacza to, że następne pokolenie dębów wyrastających z opadłych żołędzi wykiełkuje maksymalnie 40 metrów od drzewa macierzystego. Dąb produkuje jadalne nasiona, żołędzie, które są otoczone ochronną twardą skorupą.

Animals which eat acorns actually eat the seed. To get to the seed they have to break the protective shell and then they chew and eat the seed itself. Once the unprotected chewed seed eds up in a digestive system, it has not chance of sprouting again. There are three creatures that do collect whole acorns, carry then away from the tree and then bury them. These creatures are squirrels, jay birds and people.

Zwierzęta, które jedzą żołędzie, w rzeczywistości jedzą nasiona. Aby dostać się do nasionka, muszą rozbić ochronną skorupę, a następnie żują i zjadają samo ziarno. Gdy niezabezpieczone, przeżute ziarno dostanie się do układu pokarmowego, nie ma już szans na ponowne wykiełkowanie. Istnieją trzy stworzenia, które zbierają całe żołędzie, znoszą je z drzewa, a następnie zakopują. Te stworzenia to wiewiórki, sójki i ludzie.

Jays are strikingly coloured members of the crow family.

Sójki są uderzająco ubarwionymi członkami rodziny wron.

Like the other members of the crow family, they are shown to be extremely intelligent, and in fact to be as good at problem solving as a seven year old human at a problem solving task. It can be found over a vast region from Western Europe and north-west Africa to the Indian Subcontinent and further to the eastern seaboard of Asia and down into south-east Asia.

Podobnie jak inni członkowie rodziny krukowatych, okazują się niezwykle inteligentne i tak naprawdę tak samo dobre w rozwiązywaniu problemów, jak jest siedmioletni człowiek. Można je znaleźć na rozległym obszarze od Europy Zachodniej i północno-zachodniej Afryki po Subkontynent Indyjski i dalej do wschodniego wybrzeża Azji, aż do Azji Południowo-Wschodniej.

Its diet includes a wide range of invertebrates including many pest insects, beech mast and other seeds, fruits such as blackberries and rowan berries, young birds and eggs, bats, and small rodents. Its favourite food is acorns, and jey birds are often found near oaks. Jays collect and bury acorn in large cashes throughout autumn which they then use as food sources during the winter. A single bird can bury up to a several thousand acorns each year, playing a crucial role in the spread of oak woodlands.

Jej dieta obejmuje szeroką gamę bezkręgowców, w tym wiele szkodników, orzeszki bukowe (bukwie) i inne nasiona, owoce, takie jak jeżyny i jagody jarzębiny, młode ptaki i jaja, nietoperze i małe gryzonie. Jej ulubionym pożywieniem są żołędzie, a je często można znaleźć w pobliżu dębów. Sójki zbierają i zakopują żołędzie w dużych jamach przez całą jesień, które następnie wykorzystują jako źródło pożywienia zimą. Pojedynczy ptak może zakopać rocznie do kilku tysięcy żołędzi, odgrywając kluczową rolę w rozprzestrzenianiu się lasów dębowych.

Even though they are the birds of the forest edge, they are unlikely to venture into the open as they are very poor fliers and can be caught easily by any raptor bird. So jay birds probably contributed to the spread of oaks through the original hazel-pine forests but they were hardly responsible for spreading oaks into the open grasslands. Also how far would a jay bird carry the acorns from the oak tree before burying them? Jay birds are extremely territorial and would defend their territory from all intruders. This type of behaviour means that jays are unlikely to spread the acorns too far from the oak under which they found the acorns. I could not find any precise data about the territory radius of jay birds, but I would say that it is definitely not bigger than one kilometer. So the furthest jay birds would spread the acorns from the oak tree would be up to few kilometers and only through the already existing forest.

Squirrels are agile tree dwelling members of the rodent family.

Wiewiórki to zwinni, zamieszkujący drzewa członkowie rodziny gryzoni.

They are found in many regions of the world, including Europe, Asia and the Americas. There are many subspecies of which the most wide spread is the red squirrel or Eurasian red squirrel which is common throughout Eurasia.

Występują w wielu regionach świata, w tym w Europie, Azji i obu Amerykach. Istnieje wiele podgatunków, z których najbardziej rozpowszechnionym jest wiewiórka czerwona lub wiewiórka czerwona euroazjatycka, która jest powszechna w całej Eurazji.

Squirrels primarily eat nuts and seeds, but will also eat berries, fungus and insects. Squirrels horde food in small amounts in several locations when it’s abundant. Although the red squirrel remembers where it created caches at a better-than-chance level, its spatial memory is not very accurate and durable. It therefore will often have to search for its food caches when it needs them, and many are never found again. These forgotten caches of seeds, if they were buried in the ground, instead become seedlings.

Wiewiórki żywią się przede wszystkim orzechami i nasionami, ale jedzą także jagody, grzyby i owady. Wiewiórki gromadzą żywność w niewielkich ilościach w kilku miejscach, gdy jest jej pod dostatkiem. Chociaż wiewiórka ruda pamięta, gdzie utworzyła skrytki, na poziomie lepszym niż przypadek, jej pamięć przestrzenna nie jest zbyt dokładna i trwała. Dlatego często będzie musiała szukać swoich zapasów żywności, kiedy ich potrzebuje, a wiele z nich nigdy nie zostanie odnalezionych. Te zapomniane skrytki z nasionami, jeśli zostały zakopane w ziemi, zamiast tego stają się sadzonkami.

Arboreal predators which pray on squirrels include small mammals such as the pine marten, wild cats, and the stoat, which preys on nestlings as well as foxes which will pray on grown animals in the open as well as birds, including owls and raptors such as the goshawk and buzzards. Squirrels are extremely vulnerable on the ground and in the grassland which is why they never venture too far from trees.

Nadrzewnymi drapieżnikami, które żywią się wiewiórkami, są małe ssaki, takie jak kuna sosnowa, żbiki i gronostaj, który żeruje na pisklętach, a także lisy, które mogą pożerać dorosłe zwierzęta na otwartej przestrzeni, a także ptaki, w tym sowy i ptaki drapieżne, takie jak jastrząb i myszołowy. Wiewiórki są wyjątkowo łatwym łupem na ziemi i na użytkach zielonych, dlatego nigdy nie zapuszczają się zbyt daleko od drzew.

The squirrel foraging home range consist of several acres that overlap the home ranges of other squirrels. Squirrels do not defend these territories. However, there is a dominance hierarchy with others of the same species. In general, older males are dominant over females and younger squirrels. Although they seldom stray farther than few hundred meters from their nest in any one season, they are known to travel up to a few kilometres to get to a good nut tree.So the furthest squirrels would be able to spread the acorns from the oak tree would be a few kilometres and only through the already existing forest.

Zasięg żerowania wiewiórek składa się z kilku akrów, które pokrywają się z zasięgiem innych wiewiórek. Wiewiórki nie bronią tych terytoriów. Istnieje jednak hierarchia dominacji z innymi osobnikami tego samego gatunku. Ogólnie rzecz biorąc, starsze samce dominują nad samicami i młodszymi wiewiórkami. Chociaż rzadko oddalają się dalej niż kilkaset metrów od swojego gniazda w ciągu jednego sezonu, wiadomo, że pokonują nawet kilka kilometrów, aby dostać się do dobrego orzecha. Tak więc najdalszy zasięg na jaki wiewiórki byłyby w stanie rozwłóczyć żołędzie z dębu to byłoby kilka kilometrów i tylko przez istniejący już las.

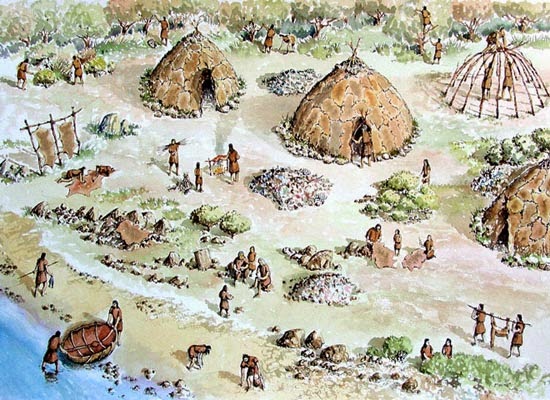

So neither squirrels nor jay birds were very likely to take acorns out of the forest into the open grassland and bury them there. But people are actually likely to do exactly that as human settlements were usually out in the open near the forest edge.

Tak więc ani wiewiórki, ani sójki raczej nie zabierały żołędzi z lasu na otwartą łąkę i tam ich nie zakopywały. Ale ludzie prawdopodobnie dokładnie wlaśnie to zrobią, ponieważ osady ludzkie zwykle znajdowały się na otwartej przestrzeni w pobliżu skraju lasu.

People would collect the acorns in the forest and then bring them to their settlement and store them in pits dug in the ground. Any acorn dropped anywhere along the way could sprout into a new oak tree. What is more, people could have carried acorns with them during their seasonal hunting or fishing migrations up north in the spring and down south in the autumn or in and out of the steppe while chasing large game. Those acorns could have been brought as the source of starch food, as acorns remain in good condition for a long time and are easy to transport. In my post about acorns in archaeology i presented enough evidence that acorns were a staple starch food of most European Mesolithic and Neolithic communities. So Mesolithic people traveling across Europe with bags of acorns is not a possibility any more but a certainty. Any acorns lost or thrown away would have sprouted along the migration or hunting routes and then spread from there radially.

Ludzie zbierali żołędzie w lesie, a następnie przynosili je do swojej osady i przechowywali w dołach wykopanych w ziemi. Każdy żołądź upuszczony gdziekolwiek po drodze może wykiełkować w nowy dąb. Co więcej, ludzie mogli nosić ze sobą żołędzie podczas sezonowych polowań lub wędrówek łowieckich na północ wiosną i na południe jesienią lub w stepie i poza nim, ścigając grubą zwierzynę. Żołędzie te mogły być przeniesione jako źródło pożywienia skrobiowego, ponieważ żołędzie długo zachowują dobrą kondycję i są łatwe w transporcie. W moim poście o żołędziach w archeologii przedstawiłem wystarczająco dużo dowodów na to, że żołędzie były podstawowym pożywieniem skrobiowym większości europejskich społeczności mezolitycznych i neolitycznych. Tak więc podróżowanie ludów mezolitu po Europie z workami żołędzi nie jest już możliwością, ale pewnością. Wszelkie zagubione lub wyrzucone żołędzie wykiełkowały wzdłuż szlaków migracyjnych lub łowieckich czlowieka, a następnie rozprzestrzeniły się stamtąd promieniście.

Oaks are said to have spread originally along the river valleys and then from the river valleys they spread into the surrounding hills. So it is presumed that oaks spread along these river valleys through normal forest creep on the same side of the river and through acorns falling into the water and then being carried away by the current down stream and diagonally across to the other side of the river. In theory this sounds plausible. In practise this is impossible to happen as acorns don’t float. Actually the only acorns that do float are fungus infested, worm ridden dead acorns. The way to separate good acorns from bad ones is to dunk them into water and throw away any acorn that floats. So acorns which fall from the oak tree into the water sink straight down to the bottom and would never sprout.

Mówi się, że dęby rozprzestrzeniły się pierwotnie wzdłuż dolin rzecznych, a następnie z dolin rzecznych rozprzestrzeniły się na okoliczne wzgórza. Przypuszcza się więc, że dęby rozprzestrzeniają się wzdłuż tych dolin rzecznych poprzez normalne pełzanie lasów po tej samej stronie rzeki i przez żołędzie wpadające do wody, a następnie przenoszone przez nurt w dół rzeki i ukośnie na drugą stronę rzeki. W teorii brzmi to wiarygodnie. W praktyce jest to niemożliwe, ponieważ żołędzie nie pływają. Właściwie jedynymi żołędziami, które pływają, są zaatakowane przez grzyby martwe żołędzie. Sposobem na oddzielenie dobrych żołędzi od złych jest zanurzenie ich w wodzie i wyrzucenie na powierzchnię wszystkich pływających żołędzi. Tak więc żołędzie, które spadają z dębu do wody, opadają prosto na dno i nigdy nie kiełkują.

Even if by any chance any of the good acorns did end up floating, they would have been carried down stream, southward not northward, as all rivers flowing just above the glacial refugiums flow southwards. But oaks did spread northwards along the big rivers. They managed to cross from the Balkans into the Panonian basin across giant rivers like Danube and Sava which completely cut the Balkans off from the rest of Europe.

Nawet jeśli jakimś cudem któreś z tych dobrych żołędzi wypłynąłby na powierzchnię, zostałby poniesiony z prądem, na południe, a nie na północ, ponieważ wszystkie rzeki płynące tuż nad refugiami lodowcowymi płyną na południe. Ale dęby rozprzestrzeniły się na północ wzdłuż dużych rzek. Udało im się przedostać z Bałkanów do Kotliny Panońskiej przez gigantyczne rzeki, takie jak Dunaj i Sawa, które całkowicie odcięły Bałkany od reszty Europy.

The only place where Balkans is connected to the rest of Europe by land is in Slovenia where we find the Alps. The maximum elevation on which oaks are found is about 1500 meters above the sea level so oaks would have had a great problem finding their way from the Balkans into the Central Europe through the Alps by themselves even with the help of the squirrels and jay birds.

Jedynym miejscem, gdzie Bałkany są połączone drogą lądową z resztą Europy, jest Słowenia, gdzie znajdują się Alpy. Najwyższe wzniesienie, na którym występują dęby, wynosi około 1500 metrów nad poziomem morza, więc dęby miałyby duży problem z samodzielnym przedostaniem się z Bałkanów do Europy Środkowej przez Alpy, nawet z pomocą wiewiórek i sójek.

But acorns could have easily been carried up and across the big rivers in dugout canoes by Mesolithic people who lived along the European coast and major rivers and who used rivers as waterways along which they traveled into the center of the European continent. These Mesolithic fishermen could have carried acorns up rivers as the source of starch food. And these acorns could have been dropped by accident or discarded anywhere along the river and on either sides of the river, where they would have sprouted into young new oaks. This would have allowed oaks to quickly spread from the Balkans refugium into the Central Europe and to be already growing in the Main river valley between 8500 and 8000 BC.

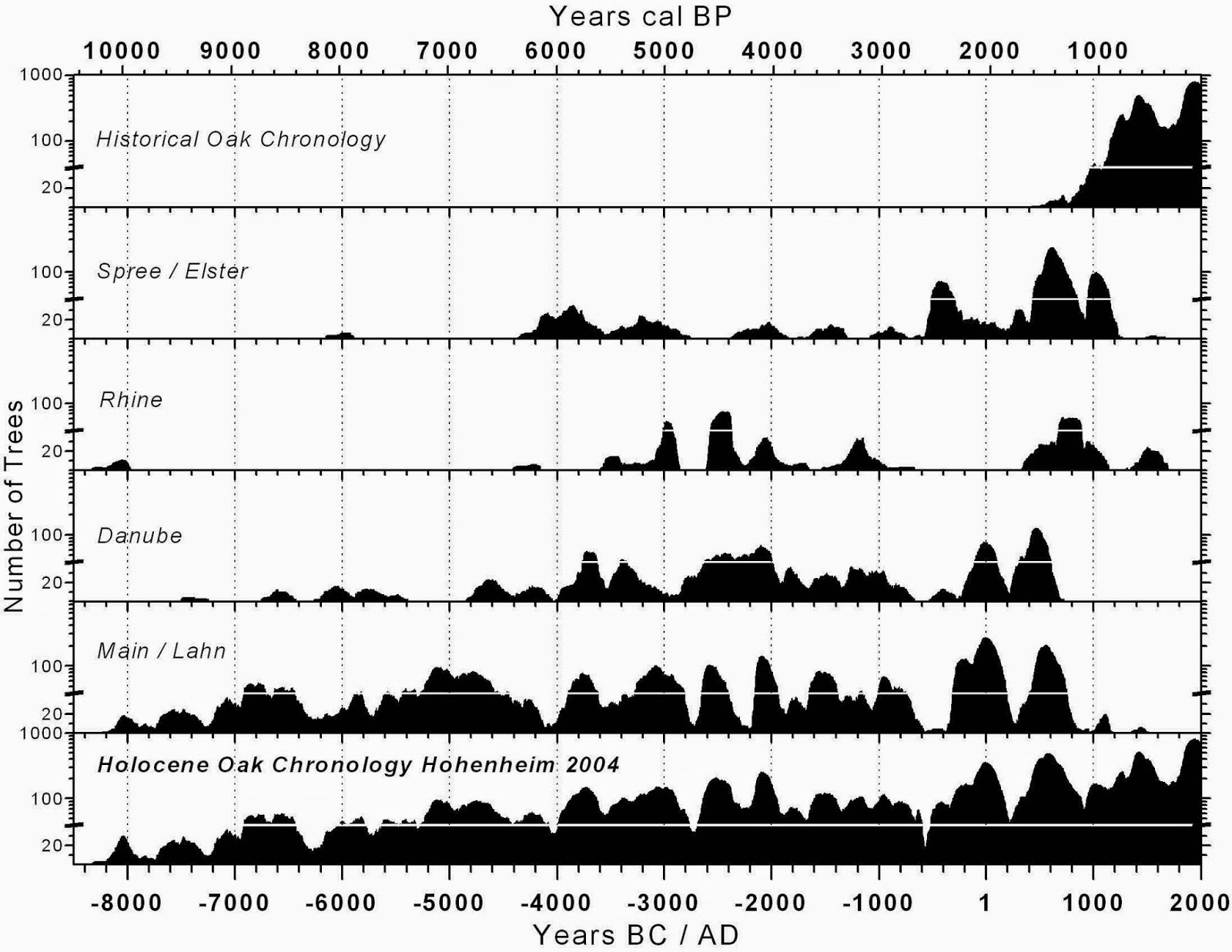

This is the Hohenheim chronology of the Oak finds in Germany. You can see that we find oaks in Rhine and Main valleys even before 8000 BC:

To jest chronologia znalezisk dębowych Hohenheim w Niemczech. Jak widać, w dolinach Renu i Menu spotykamy dęby jeszcze przed 8000 rokiem p.n.e.:

If the Main valley oaks came from the Balkan peninsula then they had to cross about 1500 km from the north Balkans to Main valley. During that trip they had to cross high mountains (Alps) and big rivers (Danube, Sava). If the Main valley oaks came from the Iberian peninsula then they also had to cross about 1500 km from the north Iberia to Main valley. During that trip they had to cross high mountains (Pyrenees) and big rivers (Garonne, Rhone, Loire). If the oaks started their expansion from the Balkans or the Iberia immediately after the end of the Younger Dryas, around 9500 BC, that would mean that they had to move at the speed of over 1 km a year to get to the Main river valley on time. These must have been some very speedy, all swimming, all mountain climbing, all singing, all dancing oaks….Not like the oaks we find today…

Jeśli dęby z doliny Menu pochodziły z Półwyspu Bałkańskiego, to musiały przebyć około 1500 km z północnych Bałkanów do doliny Menu. Podczas tej wyprawy musiały pokonać wysokie góry (Alpy) i duże rzeki (Dunaj, Sawa). Jeśli dęby doliny Main pochodziły z Półwyspu Iberyjskiego, to również musiały przebyć około 1500 km z północnej Iberii do doliny Main. Podczas tej wyprawy musiały pokonać wysokie góry (Pireneje) i duże rzeki (Garonne, Rodan, Loara). Gdyby dęby rozpoczęły swoją ekspansję od Bałkanów lub Iberii zaraz po zakończeniu młodszego dryasu, około 9500 p.n.e., oznaczałoby to, że musiałyby przemieszczać się z prędkością ponad 1 km rocznie, aby dotrzeć do doliny Menu na czas. To musiały być bardzo szybkie, pływające, wspinające się po górach, śpiewające, tańczące dęby… Nie takie jakie są dęby, które spotykamy dzisiaj…

We have the same problem if we look at the chronology of the British oaks. The first oaks were found to have arrived in Britain around 7500 BC. From there it took oaks 2000 years to reach Scotland. Based on genetic evidence, most British oaks came from the Iberian refugium.

Mamy ten sam problem, jeśli spojrzymy na chronologię dębów brytyjskich. Stwierdzono, że pierwsze dęby przybyły do Wielkiej Brytanii około 7500 pne. Stamtąd dębom zajęło 2000 lat, aby dotrzeć do Szkocji. Na podstawie dowodów genetycznych większość dębów brytyjskich pochodziła z refugium iberyjskiego.

The direct shortest distance between north Spain and southern Britain is about 1500 km. Oaks are supposed to have started spreading at some stage after 9500 BC and have arrived to Britain 2000 years later. If we accept what biologists are saying, that oak forests expand in general at maximum pace of 500 meters per year, it would take oaks 3000 years to get to Britain which means that they would not have made it in time to be found in Britain at 7500 BC.

Bezpośrednia najkrótsza odległość między północną Hiszpanią a południową Wielką Brytanią wynosi około 1500 km. Przypuszcza się, że dęby zaczęły się rozprzestrzeniać na pewnym etapie po 9500 r. pne i przybyły do Wielkiej Brytanii 2000 lat później. Jeśli przyjmiemy to, co mówią biolodzy, że lasy dębowe rozszerzają się generalnie w tempie maksymalnie 500 metrów rocznie, to dęby potrzebowałyby 3000 lat, aby dotrzeć do Wielkiej Brytanii, co oznacza, że nie zdążyłyby znaleźć się w Wielkiej Brytanii w 7500 pne.

But the path that oaks had to travel from Iberia to Britain was not straight and there were many high mountains and rivers which oaks needed to cross on their way up north.

Ale ścieżka, którą dęby musiały podróżować z Iberii do Wielkiej Brytanii, nie była prosta i było wiele wysokich gór i rzek, które dęby musiały pokonać w drodze na północ.

This would all extend the distance the oaks needed to cross on their march to Britain to about 2500 km. This means that oaks would need at least 5000 years to expand from Iberia to Britain by expanding at the rate of 500 meters a year.

To wszystko wydłużyłoby odległość, którą dęby musiały pokonać w marszu do Wielkiej Brytanii do około 2500 km. Oznacza to, że dęby potrzebowałyby co najmniej 5000 lat, aby rozszerzyć się z Iberii do Wielkiej Brytanii w tempie 500 metrów rocznie.

To make things worse according to latest data the Rhine, combined with the Schelde and Meuse, flowed to the south into the English Channel.

Co gorsza, według najnowszych danych Ren, w połączeniu ze Skaldą i Mozą, płynął na południe do kanału La Manche.

The above map shows the latest insights into how the North Sea was formed. Previously, scientists thought that the Rhine-Meuse-Schelde flowed to the north eventually joining the Ouse. But that idea proved to be wrong. One of the reasons for the southerly course of the Rhine was the forebulge that existed in the north of Holland. The weight of the ice cap upon Scandinavia pushed the earth’s crust down and the crust bulged up to the south of it. Once the ice had gone, this bulge gradually flattened. Since 18000 BC, the north of Holland has sunk some 30m. The south of Britain also used to be higher than today. As the water rose quickly we can safely assume that the Channel extended fast to the north, rendering the distance from the south of France longer by each passing day. This would extend the distance that oaks had to cover between the north Iberia and south of Britain even more to maybe 3000 km. This means that oaks would need at least 6000 years to expand from Iberia to Britain by expanding at the rate of 500 meters a year.

Powyższa mapa przedstawia najnowsze spostrzeżenia na temat powstania Morza Północnego. Wcześniej naukowcy sądzili, że Ren-Moza-Skalda płynął na północ, ostatecznie łącząc się z Ouse. Ale ten pomysł okazał się błędny. Jedną z przyczyn południowego biegu Renu było przedgórze, które istniało na północy Holandii. Ciężar pokrywy lodowej na Skandynawii zepchnął skorupę ziemską w dół, a skorupa wybrzuszyła się na południe od niej. Gdy lód zniknął, to wybrzuszenie stopniowo się spłaszczało. Od 18 000 lat pne północna Holandia obniżyła się o około 30 metrów. Południe Wielkiej Brytanii również było wyższe niż obecnie. Ponieważ poziom wody szybko się podnosił, możemy bezpiecznie założyć, że kanał szybko rozciągał się na północ, zwiększając odległość od południa Francji z każdym mijającym dniem. Zwiększyłoby to odległość, jaką dęby musiały pokonać między północną Iberią a południem Wielkiej Brytanii, nawet do około 3000 km. Oznacza to, że dęby potrzebowałyby co najmniej 6000 lat, aby rozszerzyć się z Półwyspu Iberyjskiego do Wielkiej Brytanii w tempie 500 metrów rocznie.

But this is all based on a completely wrong premise that oak forest edge can move outwards at the rate between 250 and 500 meters a year, which is actually impossible. Oak forest edge can’t move at the rate of even a 250 meter per year. The reason for that is that new oak tree will not produce any acorns until the tree is at least 25 years old. If we take this into account we get the real natural oak forest expansion speed.

Ale to wszystko opiera się na całkowicie błędnym założeniu, że skraj lasu dębowego może przesuwać się na zewnątrz w tempie od 250 do 500 metrów rocznie, co w rzeczywistości jest niemożliwe. Skraj lasu dębowego nie może przesuwać się z prędkością nawet 250 metrów na rok. Powodem tego jest to, że nowy dąb nie wyda żołędzi, dopóki drzewo nie osiągnie wieku co najmniej 25 lat. Jeśli weźmiemy to pod uwagę, otrzymamy rzeczywistą prędkość ekspansji naturalnego lasu dębowego.

If the acorn just falls down and sprouts it can’t fall more than the maximum height or diameter of the tree which is not more than 120 meters. At best, if we take into account a possibility of an adventurous jay bird or a squirrel, which would take an acorn as far away as possible from the oak tree to bury it, that would still mean that the acorn would end up no more than few kilometres from the tree trunk. If the acorn then managed to sprout into a new oak, the expansion of the edge of the oak forest would then stop for next 25 years until the new oaks growing at the new edge of the oak forest start producing their own acorns. This means that the oak forests edge would not move 500 meters a year but at most 5000 meters (5 km) every 25 years. This would mean that even if we accept that the distance that oaks needed to cover to get from the north Iberia to the southern England or from the Balkans to the Main valley was only 1500 km, it would have taken oaks 12 500 years to cover that distance by „natural” means.

Jeśli żołądź po prostu spadnie i wykiełkuje, nie może spaść więcej niż maksymalna wysokość lub średnica drzewa, która nie przekracza 120 metrów. W najlepszym przypadku, jeśli weźmiemy pod uwagę możliwość żądnej przygód sójki lub wiewiórki, która zabrałaby żołądź jak najdalej od dębu, aby go zakopać, nadal oznaczałoby to, że żołądź skończyłby nie dalej niż kilka kilometrów od pnia drzewa. Gdyby z żołędzia udało się następnie wykiełkować w nowy dąb, ekspansja skraju lasu dębowego zatrzymałaby się na następne 25 lat, aż nowe dęby rosnące na nowym skraju lasu dębowego zaczną produkować własne żołędzie. Oznacza to, że skraj lasów dębowych przesuwałby się nie o 500 metrów rocznie, ale najwyżej o 5000 metrów (5 km) co 25 lat. Oznaczałoby to, że nawet jeśli przyjmiemy, że odległość, jaką dęby musiały pokonać, aby dostać się z północnej Iberii do południowej Anglii lub z Bałkanów do doliny Menu, wynosiła zaledwie 1500 km, pokonanie tej odległości zajęłoby dębom 12 500 lat odległość za pomocą „naturalnych” środków.

But if people brought oaks with them, travelling in their dugout canoes along the Atlantic coast, then oaks could have arrived to Britain from their Iberian refugium within a few years. Equally if people brought oaks with them, travelling in their dugout canoes up the river Danube and then down the river Rhine, then oaks could have arrived to Britain from their Balkan refugium within a few years.

Ale gdyby ludzie przywieźli ze sobą dęby, przemieszczając się swoimi dłubankami wzdłuż wybrzeża Atlantyku, to dęby mogłyby przybyć do Wielkiej Brytanii z ich iberyjskiego refugium w ciągu kilku lat. Podobnie, gdyby ludzie przywieźli ze sobą dęby, podróżując dłubankami w górę Dunaju, a następnie w dół Renu, wówczas dęby mogłyby przybyć do Wielkiej Brytanii z ich bałkańskiej ostoi w ciągu kilku lat.

This means that there is a strong possibility that oaks did not spread naturally back into northern Europe from the Mediterranean refugiums . There is a strong possibility that oaks were imported into Britain and Ireland, and into the rest of northern Europe by the migrating hunters-gatherers and fishermen. For these Mesolithic boat people rivers were not barriers. They actually used rivers as their main migration pathways. This is why we find that the oak expansion pattern is along river valleys and then radially into the hills.

Oznacza to, że istnieje duże prawdopodobieństwo, że dęby nie rozprzestrzeniły się w sposób naturalny z powrotem do północnej Europy ze śródziemnomorskich ostoi. Istnieje duże prawdopodobieństwo, że dęby zostały sprowadzone do Wielkiej Brytanii i Irlandii oraz do reszty północnej Europy przez migrujących łowców-zbieraczy i rybaków. Dla tych mezolitycznych łodzian rzeki nie były barierami. W rzeczywistości używali rzek jako głównych szlaków migracji. Dlatego stwierdzamy, że wzorzec ekspansji dębów przebiega wzdłuż dolin rzecznych, a następnie promieniście w kierunku wzgórz.

There is actually a direct proof that acorns were were spread into northern Europe from their Mediterranean refugiums by people. And it can be found in Walsh Marches. Based on genetic evidence, most British oaks came from the Iberian refugium. But not all. The oak population from the border between England and Wales (the Welsh Marches) possessed a haplotype which is common in the Balkan area. This means that it is possible that Britain had been recolonized by oaks from more than one refugium. How did these Balkan oaks arrive to England and Wales? The distance between Balkans and Wales is at least 2500 km. Just imagine how long it would have taken Balkan oaks to arrive to Wales if they were to be spread only by acorn drop, or by squirrels and jay birds…And by the way the closest oaks possessing the same genetic type as Welsh oaks, are scattered individuals along the north coast of France and in a clustered population near Rennes, 300 and 450 km distance from the Welsh Marches. This completely removes the possibility that the Welsh Marches oaks arrived by means of forest creep. They had to be brought to Wales from the Balkans by people. The only question is when.

W rzeczywistości istnieje bezpośredni dowód na to, że żołędzie zostały przeniesione do północnej Europy z ich śródziemnomorskich ostoi przez ludzi. I można go znaleźć w Walsh Marches. Na podstawie dowodów genetycznych większość dębów brytyjskich pochodziła z refugium iberyjskiego. Ale nie wszystkie. Populacja dębu z pogranicza Anglii i Walii (Walijskie Marchie) posiadała haplotyp powszechny na Bałkanach. Oznacza to, że możliwe jest, że Wielka Brytania została ponownie skolonizowana przez dęby z więcej niż jednego refugium. Jak te bałkańskie dęby dotarły do Anglii i Walii? Odległość między Bałkanami a Walią wynosi co najmniej 2500 km. Wyobraź sobie, ile czasu zajęłoby bałkańskim dębom przybycie do Walii, gdyby były roznoszone tylko przez pojedyncze żołędzie, wiewiórki i sójki… A tak przy okazji, najbliższe dęby posiadające ten sam typ genetyczny co dęby walijskie, to rozproszone osobniki wzdłuż północnego wybrzeża Francji oraz skupiska populacji w pobliżu Rennes, w odległości 300 i 450 km od Walijskich Marchii. To całkowicie eliminuje możliwość, że dęby Welsh Marches przybyły za pomocą pełzania lasu. Do Walii musieli je sprowadzić ludzie z Bałkanów. Pytanie tylko kiedy.

It’s even not unthinkable that the Mesolithic people has deliberately sown acorns. It’s one of the easiest things to do. You stick the acorn into the ground and forget about it. The young trees do not require attention and can take care of themselves. It takes 25 years until new oaks started to produce acorns. But once they do start to produce acorns, they would continue producing them for hundreds of years and would give one of the biggest yields per year of any edible plant. I believe that this must have been known to Mesolithic people and there is more and more evidence that Mesolithic people deliberately planted and cultivated „wild” crops millenniums before „agriculture” was invented.

Jest nawet do pomyślenia, że lud mezolityczny celowo zasiał żołędzie. To jedna z najłatwiejszych rzeczy do zrobienia. Wbijasz żołądź w ziemię i zapominasz o tym. Młode drzewka nie wymagają uwagi i potrafią same o siebie zadbać. Minęło 25 lat, zanim nowe dęby zaczęły produkować żołędzie. Ale kiedy zaczną produkować żołędzie, będą to kontynuować przez setki lat i dadzą jeden z największych plonów rocznie ze wszystkich roślin jadalnych. Wierzę, że musiało to być znane ludom mezolitu i jest coraz więcej dowodów na to, że ludzie mezolitu celowo sadzili i uprawiali „dzikie” uprawy na tysiąclecia przed wynalezieniem „rolnictwa”.

I will talk about cultivation versus agriculture in one of my next posts. Until then have fun.

O uprawie (kultywacji) kontra rolnictwie (agrokulturze) opowiem w jednym z moich następnych postów. Do tego czasu baw się dobrze.