photo by Kira Bialczynska ®All rights reserved

photo by Kira Bialczynska ®All rights reserved

Sielanka, czyli Sri Lanka

Nazwa państwa Sri Lanka, przyjęta w 1972, oznacza w sanskrycie „olśniewający kraj”. Obecna nazwa jest współczesną adaptacją nazwy występującej w Ramajanie, gdzie wyspa znana jest jako Lanka.

W Ramajanie wyspa znana jest także jako Lankadweepa (dwepa – wyspa) oraz Lakdiva (diva – wyspa). Późniejszą tradycyjną nazwą była Lakbima. Lak to skrót od Lanka.

Podobną etymologię nazwy wyspy ma tamilska İlankai.

Co ciekawe nie znajdziecie tutaj etymologii wywodzonej od dewa-bóg, dawa – dawać/dzielić, Boska Lanka, Dewpa-Dwepa – Boska Wyspa. Egzotyczne w zapisie nazwy miejscowe wymawia się dziwnie znajomo i zapisuje po palijsku – a palijski jak wiemy bliski jest i sanskrytowi i polskiemu.

Czy to przypadkowe zbieżności brzmień: Dambulla – Dombulu, Dąbuła, Dymbula, Dębula; Sigiria – ZaGORIJE, Zagórze, Zagorje. Czy to nie brzmi podobnie do przypisywanej Słowianom (być może Goljadziom, Wandalom lub Gotom) jaskini w Hiszpanii, której nazwa ma słowiano-wenedyjskie brzmienie: Zugarramurdi (Zagaromordia). W tejże jaskini odbywały się obrzędy Kresu (Kupaliów) – krzesania-zagaru, zagorzenia rytualnego Ognia, a do dzisiaj obchodzi się tutaj letnie przesilenie w blasku pochodni i naturalnego ognia upamiętniające też spalone na stosach w tym miejscu i w Kraju Basków czarownice – wiedźmy starej Wiary Przyrody.

Czy to przypadkowa całkowicie zbieżność nazwy Królestwa Polonar, którego stolicą była Pollonaruwa, z blisko brzmiącą nazwą polonorum – Regi Polonorum. Polona Regni – Korona Polska, co z kolei wywodzi się z wici etymologicznej od rok – rok-god, rocznik, czy rock – skała, czy Krok – władca, regent-regni – regalia – symbole władzy, reg – władający skałą, będący i konarem i korzeniem- czyli krakiem – królem-korzeniem i zarazem królem-konarem pniem/gałęzią rodu, a także regiem– ziarnem (co brzmi też w nazwie wyspy Rugii-Ruji), z którego roślina wyrasta, tak drzewo jak i zboże (reż-pszenica, rżyto-żyto, ryg- ryż).

(O Zagoramordji czytajcie np. tutaj)

Sinhala oraz Sihalam

Nazwa Cejlon (ang. Ceylon) sięga swoim rodowodem sanskryckiego słowa sinha (lew). Sinhala może być rozumiana jako „krew lwa”. Ponieważ na Sri Lance nie występują lwy, nazwa ta mogła odnosić się do lokalnego bohatera, dziadka króla Vijayi. W języku pāli, sanskrycka nazwa Sinhala to Sihalam, wymawiana jako Silam.

Salike

Ptolemeusz nazywa Sri Lankę jako Simoundou lub Simundu (prawdopodobnie jako Silundu), która to nazwa upowszechniła się w starożytnym świecie. Ptolemeusz używał także nazwy Palai-Simundu (z gr. palai – stara, lub z sanskrytu jako „miejsce pochodzenia świętego prawa”), jako że w owym czasie wyspa była jednym z głównych ośrodków buddyzmu.

Cejlon

Biorąc pod uwagę pochodzącą z sanskrytu nazwę Sinhala (poprzez palijską nazwę Sihalam), Ammianus Marcellinus (IV w.) nazwał mieszkańców wyspy Serandives, natomiast grecki podróżnik Kosmas Indikopleustes (VI w.) nazwał wyspę Sielen Diva (wyspa Sielen). Ta ostatnia została zaadoptowana przez inne języki: łac. Selan, port. Ceilão, hiszp. Ceilán, franc. Selon, hol. Zeilan, Ceilan i Seylon oraz ang. Ceylon, czy w końcu pol. Cejlon.

Podobną etymologię mają inne nazwy Sri Lanki, np. Serendiva, Serendivus, Sirlediba, Sihala, Sinhale, Seylan, Sinhaladveepa, Sinhaladweepa, Sinhaladvipa, Sinhaladwipa, Simhaladveepa, Simhaladweepa, Simhaladvipa, Simhaladwipa, Sinhaladipa, Simhaladeepa itd.

Abu Rihan Muhammad bin Ahmad (X w.) nazwał wyspę Singal-Dip, jednak w języku arabskim przyjęto później nazwę Serendib lub Sarandib, pochodzącą z perskiego Serendip. Nazwa ta użyta została w perskiej bajce „Ksiązniczka z Serendip”, w której bohaterowie dokonują nieoczekiwanych odkryć i znajdują rzeczy, których nie poszukiwali.

Od tej nazwy, Horace Walpole, 4. hrabia Orford w roku 1754 stworzył angielskie słowo serendipity (pol. serendypność – sytuacja, w której przypadkowo dokonuje się szczęśliwego odkrycia, zwłaszcza wtedy, gdy szuka się czegoś zupełnie innego).

Od tej nazwy, Horace Walpole, 4. hrabia Orford w roku 1754 stworzył angielskie słowo serendipity (pol. serendypność – sytuacja, w której przypadkowo dokonuje się szczęśliwego odkrycia, zwłaszcza wtedy, gdy szuka się czegoś zupełnie innego).

Później w języku arabskim używano Tilaan i Cylone, mających podobną jak „Cejlon” etymologię.

Heladiva

Nazwy Heladiva oraz Heladveepa mogą pochodzić od ludu Hela, zamieszkującego Sri Lankę przed przybyciem ludności z kontynentu (Indusów i Tamilów).

Tâmraparnî

Inną nazwą, która była używana w zachodnim świecie, była nazwa wspomniana przez króla Vijayę (indyjskiego najeźdzcę) – Tâmraparnî („liść o miedzianym kolorze”), a zaadaptowaną do języka pali jako Tambaparni. Oficerowie Aleksandra Wielkiego oraz Megastenes używali określenia Taprobanê.

Później nazwa ta pojawiała się w utworach Johna Miltona (w „Paradise lost”), oraz w Miguela de Cervantesa (jako Trapobana w „Don Kichocie).

Inne nazwy

Pośród innych nazw Sri Lanki należy wymienić tamilską İlanare, arabską Tenerism („wyspa rozkoszy”). Wyspa posiadała także popularne określenia: „Wyspa Nauki” (ze względu na to, że była jednym z ważnych centrów buddyzmu), „Łza Indii” (ze względu na swój kształt i położenie względem Półwyspu Indyjskiego) oraz „Perła Oceanu Indyjskiego”.

Odmiana gramatyczna

Odmiana nazwy tego państwa przez przypadki może sprawić pewne trudności, jak i utworzenie rzeczownika określającego obywatela Sri Lanki. Przy odmianie w niektórych przypadkach zachodzi oboczność. Mówimy o Sri Lance. Odwiedzamy zaś Sri Lankę. Obywatel Sri Lanki to Lankijczyk, obywatelka to Lankijka. Przymiotnik brzmi: lankijski.

Lanka (Sanskrit: लंका Sri lankā meaning „respected island”, Sinhala: (Langkapura), Malay: Langkapuri, Tamil: Ilankai, Javanese and Indonesian: Alengka or Ngalengka) is the name given in Hindu mythology to the island fortress capital of the legendary king Ravana in the great Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The fortress was situated on a plateau between three mountain peaks known as the Trikuta Mountains. The ancient City of Lankapura is thought to have been burnt down by Lord Hanuman. After the King Ravana was killed by Lord Rama with the help of the former’s brother Vibhishana, Vibhishana was crowned King of Lankapura by Lord Rama after which he ruled the kingdom.

His descendants ruled the kingdom even during the period of the Pandavas. According to the epic, the Mahabharata, the Pandava Sahadeva had visited this kingdom during his southern military campaign for the Rajasuya sacrifice of Pandava king Yudhisthira.

Węsiory-staniczki – staniczki, czyli małe stanice, trójkątne chorągiewki w boskich barwach (maściach-mościach). Wbrew pozorom nazwa stanika – nie jest od tejże odległa – staniki – małe trójkąty z materiału, osłaniające piersi.

Rakszas, Rakszasa ( sanskryckie: राक्षसः trl. rākṣasaḥ, japoński: 羅刹天 Rasetsuten ) – w mitologii hinduskiej: demon-ludojad, tytan, rodzaj złośliwego, złego ducha, olbrzyma, szkodnika, złośliwy potwór-olbrzym grasujący po zapadnięciu zmierzchu i żywiącego się surowym mięsem, także ludzkim. W hinduizmie symbolizuje naturę mroczną (tamas), czyli taką w której przeważa nienawiść, naturę złą, która zadaje innym niezgodne z dharmą (religią) rany, cierpienia i krzywdy. Rodzaj żeński to rakszasi. Wodzem rakszasów jest Kuwera. [1]

Etymologia

Etymologia

Słowo rakszasa ma pochodzenie sanskryckie. Tradycyjnie wywodzone jest od sanskryckiego rdzenia rakṣ o znaczeniach strzec, pilnować[2].

Geneza

Wedle indyjskich mitów, cała rasa rakszasów została pierwotnie stworzona przez Brahmę, boga-stwórcę, jednak uległa degeneracji. Rakszasowie byli strażnikami cennych pierwotnych wód ziemi. Mitologia ludowa przypisuje rakszasom odrażający wygląd, wielką otyłość, nienaturalnie długie ręce, kształty olbrzymów lub karłów, większą liczbę nóg, obwisłe brzuchy i piersi (u rakszasic), kończyny zakończone szponami, wystające zęby czy wyłupiaste oczy. Opisuje się głowy rakszasów jako głowy gadów, osłów, koni lub słoni. Odpowiedzialni są za gwałcenie kobiet oraz wypijanie krwi czyli wampiryzm. Mogą przybierać na ciele barwy czerwoną, niebieską lub zieloną, wydają okropne ryczące dźwięki, a kiedy zabijają zwierzęta lub ludzi dla pozyskania ich mięsa, rozrywają ciało w bardzo nietypowy, makabryczny sposób. Można powiedzieć, że obraz rakszasa to obraz wszelkich patologii i deformacji oraz okrucieństwa i wynaturzenia.

Przedstawiciele

Najbardziej znanym przedstawicielem rakszasów jest Rawana, król Lanki, który porwał Sitę, małżonkę króla Rama, co jest przedmiotem eposu Ramajana. Historia zbrodni Rawany podkreśla jedynie wszelkie negatywne cechy rakszasów jako złych demonów, złych duchów, które jednak mogą się inkarnować w ludzkie ciała, które wedle wielu ruchów hinduskich, będą mieć jakieś rakszasowe oznaki w postaci wspomnianych deformacji. Inna część hinduskich grup kultowych zabrania nawet wymawiania nazwy rakszas, gdyż może to ich zdaniem wywoływać złego ducha, demona z okolicy. Dla wielu wyznawców hinduizmu opisane deformacje bywały w historii podstawą do odsuwania się od osób o cechach rakszasowych, podczas gdy dla innych były mobilizacją do pomagania takim osobom jako obdarzonym złą karmą, czyli złym losem odziedziczonym z poprzednich wcieleń lub po przodkach. Uważa się jednak powszechnie, że rakszasowe deformacje są odzwierciedleniem cech i skłonności, które są w jakiś sposób nieczyste, demoniczne.

Cechy

Rakszasa potrafi udawać przyjaciela i pokazywać się w boskich, pięknych kształtach, jednak nie potrafi tego utrzymać zbyt długo i z udawanego przyjaciela szybko staje się zajadłym wrogiem na śmierć i życie. Typowo opisywana cecha rakszasów w dziedzinie moralnej to zaprzyjaźnianie się z gospodarzem domostwa po to, aby uwieść jego żonę. Opisuje się też przypadki tak zwanych fałszywych wielbicieli, którzy przymilają się do jakiegoś guru, po to tylko, aby zniszczyć jego misję czy wręcz zabić przywódcę i zająć jego miejsce. Zdolność ukazywania się rakszasów w pięknych kształtach odnoszona jest do błędnych wizji i fałszywych objawień jakiś nieziemskich istot podających się za dawnych bogów, dewów, aniołów, etc. Hinduizm generalnie przyjmuje zasadę weryfikowania wizji i stanów mistycznych natchnień przez uznanych i sprawdzonych, żyjących nauczycieli czy guru. Niektóre ruchy działające na marginesie hinduizmu odrzucają całą mitologię związaną z rakszasami.

Rawana – czarny charakter w indyskim eposie Ramajana, rakszasa, który podstępnie zagarnął tron Lanki i porwał żonę Rama, Sitę. Przedstawiany jako demon o dziesięciu głowach i dwudziestu rękach, stąd alternatywne imiona Daśamukha (Dziesięciolicy), Daśakantha (Dziesięciogłowy). W Ramakien, tajskiej wersji eposu nazywany Tosakan, w jawajskiej Dasamuka[1].

Rawana – czarny charakter w indyskim eposie Ramajana, rakszasa, który podstępnie zagarnął tron Lanki i porwał żonę Rama, Sitę. Przedstawiany jako demon o dziesięciu głowach i dwudziestu rękach, stąd alternatywne imiona Daśamukha (Dziesięciolicy), Daśakantha (Dziesięciogłowy). W Ramakien, tajskiej wersji eposu nazywany Tosakan, w jawajskiej Dasamuka[1].

Łamał zasady prawa wobec ludzi i bogów. Naraził się Śiwie usiłując przesunąć górę Kajlas, na której Śiwa tulił swoją żonę Parwati. Oburzony Śiwa przyciskając górę do ziemi, przygniótł ręce Rawany. Wyraz jego bólu był tak przeraźliwy, że właśnie wtedy zyskał on przydomek Rawana – Krzykacz, Wyjec. Scenę tę przedstawiono m.in. na płaskorzeźbie w słynnej świątyni Kailaś w Elurze.

Dambulla

W polsko-katolickiej Wikipedii i na polskich oficjalnych stronach internetowych po polsku tylko tyle:

Dambulla miasto w środkowej części Sri Lanki położone 148 km na wschód od Kolombo. W mieście znajduje się Złota świątynia Dambulla wpisana na listę światowego dziedzictwa UNESCO.

16 października 2006 miał tam miejsce atak terrorystyczny, w którym zginęły 92 osoby.

Złota Świątynia Dambulla, świątynia buddyjska składająca się z pięciu jaskiń powstawała w okresie od I wieku p.n.e. do XVIII wieku. Położona w centralnej części Sri Lanki w miejscowości Dambulla.

Na świątynie składają się groty:

- Dewadżara Wihara (Świątynia Króla-Boga) z rzeźbą przedstawiającą odpoczywającego Buddy i dobrze zachowanymi malowidłami ściennymi;

- Maharadża Wihara (Świątynia Wielkiego Króla), najwieksza ze wszystkich z najwspanialszymi malowidłami ściennymi przedstawiającymi sceny z życia Buddy i historii wyspy;

- Maha Alut Wihara (Wielka Nowa Świątynia), najmłodsza z świątyń pochodząca z XVIII wieku;

- świątynia poświęcona królowej Somawathi;

- piąta świątynia była remontowana w XVIII wieku;

więc dalej po angielsku

is a big town, situated in the Matale District, Central Province of Sri Lanka, situated 148 km north-east of Colombo and 72 km north of Kandy. Due to the major junction, it’s the distribution centre of vegetable in the country.

Major attractions of the area include the largest and best preserved cave temple complex of Sri Lanka, and the Rangiri Dambulla International Stadium, famous for being built in just 167 days. The area also boasts to have the largest rose quartz mountain range in South Asia, and the Iron wood forest, or Namal Uyana.

Ibbankatuwa prehistoric burial site near Dhambulla cave temple complexes is the latest archaeological site of significant historical importance found in Dambulla, which is located within 3 kilometers of the cave temples providing evidence on presence of indigenous civilisations long before the arrival of Indian influence on the Island nation.

The area is thought to be inhabited from as early as the 7th to 3rd century BC. Statues and paintings in these caves date back to the 1st century BC. But the paintings and statues were repaired and repainted in 11th, 12th, and 18th century AD. The caves in the city provided refuge to King Valagamba (also called Vattagamini Abhaya) in his 14 year long exile from the Anuradapura kingdom. Buddhist monks meditating in the caves of Dambulla at that time provided the exiled king protection from his enemies. When King Valagamba returned to the throne at Anuradapura kingdom in the 1st century BC, he had a magnificent rock temple built at Dambulla as a gratitude to the monks in Dambulla.

Ibbankatuwa Prehistoric burial site near Dhambulla, where prehistoric (2700 years old) human skeletons were found according to scientific analysis gives evidence on civilisations in this area long before arrival of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Evidence of ancient people living on agriculture have been detected in this area for over 2700 years according to archaeological findings. (750 BC)

It was earlier known as Dhamballai. This was ruled by Kings like Raja Raja Chola, Rajendra Chola, etc. during their tenure in the late 10th century and early 11th century.

Dambulla cave temple

It is the largest and best preserved cave temple complex in Sri Lanka. The rock towers 160 m over the surrounding plains.There are more than 80 documented caves in the surrounding. Major attractions are spread over 5 caves, which contain statues and paintings. This paintings and statues are related to Lord Buddha and his life. There are a total of 153 Buddha statues, 3 statues of srilankan kings and 4 statues of god and goddess. The latter 4 include two statues of Hindu gods, Vishnu and Ganesh. The murals cover an area of 2,100 m². Depictions in the walls of the caves include Buddha’s temptation by demon Mara and Buddha’s first sermon.

Time line of the Caves

- 7th to 3rd century BC: Early inhabitants

- 1st century BC: Paintings and statues

- 5th century AD: The stupa was built

- 12th century AD: Addition of the statues of Hindu gods

- 18th century AD: Most of what we see today

- 19th century AD: An additional cave and some repainting

- 20th century AD:UNESCO restoration and lighting….

Dambulla Rock Temple

Dambulla from: http://www.lankalibrary.com/heritage/dambulla.htm

Dating back to the 1st Century BC, this is the most impressive cave temple in Sri Lanka. It has five caves under a vast overhanging rock, carved with a drip line to keep the interiors dry. In 1938 the architecture was embellished with arched colonnades and gabled entrances. Inside the caves, the ceilings are painted with intricate patterns of religious images following the contours of the rock. There are images of the Lord Buddha and bodhisattvas, as well as various gods and goddesses.

The temple is composed of five caves, which have been converted into shrine rooms. The caves, built at the base of a 150m high rock during the Anuradhapura (1st Century BC to 993 AD) and Polonnaruwa times (1073 to 1250), are by far the most impressive of the many cave temples found in Sri Lanka. Access is along the gentle slope of the Dambulla Rock, offering a panoramic view of the surrounding flat lands, which includes the rock fortress Sigiriya, 19kms away. Families of friendly monkeys make the climb even more interesting. Dusk brings hundreds of swooping swallows to the cave entrance. The largest cave measures about 52m from east to west, and 23m from the entrance to the back, this spectacular cave is 7m tall at its highest point. Hindu deities are also represented here, as are the kings Valgamba and Nissankamalla, and Ananda – the Buddha’s most devoted disciple.

Within these shrine rooms is housed a collection of one hundred and fifty statues of the Buddhist Order and the country’s history. These statues and paintings are representative of many epochs of Sinhala sculpture and art. The Buddha statues are in varying sizes and attitudes – the largest is 15 metres long. One cave has over 1,500 paintings of Buddha covering the ceiling.

The Dambulla cave monastery is still functional and remains the best-preserved ancient edifice in Sri Lanka. This complex dates from the 3rd and 2nd Centuries BC, when it was already established as one of the largest and most important monasteries. King Walagambahu is traditionally thought to have converted the caves into a temple in the 1st century BC. Exiled from Anuradhapura, he sought refuge here from South Indian usurpers for 15 years. After reclaiming his capital, the King built a temple in thankful worship. Many other kings added to it later and by the 11th century, the caves had become a major religious centre and still are. King Nissanka Malla gilded the caves and added about 70 Buddha statues in 1190. During the 18th century, the caves were restored and painted by the Kandyan Kings.

The first cave is called Devarajalena, or „Cave of the Divine King.” An account of the founding of the monastery is recorded in a first-century Brahmi inscription over the entrance to the first cave. This cave is dominated by the 14-meter statue of the Buddha, hewn out of the rock. It has been repainted countless times in the course of its history, and probably received its last coat of paint in the 20th century. At his feet is Buddha’s favorite pupil, Ananda; at his head, Vishnu, said to have used his divine powers to create the caves.

In the second and largest cave, in addition to 16 standing and 40 seated statues of Buddha, are the gods Saman and Vishnu, which pilgrims often decorate with garlands, and finally statues of King Vattagamani, who honored the monastery in the first century B.C., and King Nissanka Malla, responsible in the 12th century for the gilding of 50 statues, as indicated by a stone inscription near the monastery entrance. This cave is accordingly called Maharajalena, „Cave of the Great Kings.” The Buddha statue hewn out of the rock on the left side of the room is escorted by wooden figures of the Bodhisattvas Maitreya (left) and Avalokiteshvara or Natha (right). There is also a dagoba and a spring which drips its water, said to have healing powers, out of a crack in the ceiling. Valuable tempera paintings on the cave ceiling dating from the 18th century depict scenes from Buddha’s life, from the dream of Mahamaya to temptation by the demon Mara. Further pictures relate important events from the country’s history

The third cave, the Maha Alut Vihara, the „Great New Monastery,” acquired ceiling and wall paintings in the typical Kandy style during the reign of King Kirti Sri Rajasinha (1747-1782), the famous Buddhist revivalist. In addition to the 50 Buddha statues, there is also a statue of the king.

The fourth and fifth caves are smaller; they date from a later period and are not of such high quality. A small Vishnu Devale between

Sigirija

Sigirija (w wolnym tłumaczeniu „Lwia Skała”) – stanowisko archeologiczne w Sri Lance, znajdują się tam ruiny starożytnego pałacu i twierdzy zbudowanych podczas panowania króla Kassapy (473–491) na szczycie 370-metrowej skały. Sigirija jest jedna z siedmiu miejsc w Sri Lance na Liście światowego dziedzictwa kulturowego i przyrodniczego.

Skała to ogromna bryła magmy – pozostałość po dawno wygasłym i zapadniętym wulkanie. Położona na względnie płaskiej wyżynie jest widoczna z odległości wielu kilometrów.

Legenda

W drugiej połowie V wieku n.e. na Cejlonie panował król Dhatusen. Władca miał dwóch synów – Mogallana i Kassapę. Tron po ojcu miał objąć starszy Mogallan, ale (młodszy i z nieprawego łoża) Kassapa nie zamierzał ustąpić. W roku 473 dokonał przewrotu pałacowego, uwięził, a następnie zamordował ojca (podobno stary król został żywcem zakopany w ziemi, gdyż nie chciał wyjawić miejsca ukrycia swych skarbów), ale Mogallan mu się wymknął i na czele garstki zwolenników zbiegł do Indii.

Kassapa został królem, ale nie opuszczał go strach przed zemstą przyrodniego brata. Dlatego postanowił zbudować zamek na szczycie wybitnej skały położonej w centrum wyspy, w pobliżu jeziora Mineria. Ogromnym wysiłkiem wzniesiono na szczycie pałac i system fortyfikacji. Wykuto zbiorniki na wodę i spichlerze na żywność, by można było przetrzymać nawet kilkumiesięczne oblężenie. Jedyną drogę na szczyt stanowiły wąskie schodki wykute w skale.

Mogallan długo zbierał siły, ale wreszcie, w roku 491, a więc po osiemnastu latach panowania Kassapy, na czele wielkiej armii wylądował na wyspie i zaatakował. Kassapa przegrał walną bitwę i podobno popełnił samobójstwo podcinając sobie gardło własnym sztyletem[1] w obliczu przeważających sił wroga.

Sigirija dzisiaj

Do dnia dzisiejszego zachowały się jedynie fundamenty pałacu i umocnień, a na ścianach skalnych dobrze zachowane malowidła przedstawiające – jak się można domyślać – damy dworu lub nałożnice królewskie. Zrekonstruowano początkową partię schodów, które wychodzą spomiędzy dwóch kamiennych lwich łap. Dla wygody turystów zbudowano też wygodne schody na stalowej konstrukcji.

Przewodniki turystyczne zachęcają do oglądania resztek twierdzy i Górnego Pałacu, położonej w połowie wysokości galerii malowideł naściennych oraz – u podstawy skały – Dolnego Pałacu i umocnień oraz ogrodów pałacowych.

Oczywiście z polskiej Wikipedii – kastrowanej przez cenzurę katolicką nie dowiecie się, że to była świątynia Wiary Przyrody – trzeba niestety czytać wersję ANGIELSKĄ:

Sigiriya (Lion’s rock, Sinhalese) is a town with a large stone and ancient rock fortress and palace ruin in the central Matale District of Central Province, Sri Lanka, surrounded by the remains of an extensive network of gardens, reservoirs, and other structures. A popular tourist destination, Sigiriya is also renowned for its ancient paintings (frescos),[1] which are reminiscent of the Ajanta Caves of India. It is one of the eight World Heritage Sites of Sri Lanka.

Sigiriya may have been inhabited through prehistoric times. It was used as a rock-shelter mountain monastery from about the 5th century BC, with caves prepared and donated by devotees of the Buddhist Sangha. According to the chronicles as Mahavamsa the entire complex was built by King Kashyapa (477 – 495 CE), and after the king’s death, it was used as a Buddhist monastery until 14th century.

The Sigiri inscriptions were deciphered by the archaeologist Senarath Paranavithana in his renowned two-volume work, published by Cambridge, Sigiri Graffiti and also Story of Sigiriya.[2]

Location and geographical features

Location and geographical features

Sigiriya is located in the Matale District in the Central Province of Sri Lanka.[3][4] It is within the cultural triangle, which includes five of the eight world heritage sites in Sri Lanka.[5]

The Sigiriya rock is a hardened magma plug from an extinct and long-eroded volcano. It stands high above the surrounding plain, visible for miles in all directions. The rock rests on a steep mound that rises abruptly from the flat plain surrounding it. The rock itself rises approximately 370 m (1,214 ft) above sea level and is sheer on all sides, in many places overhanging the base. It is elliptical in plan and has a flat top that slopes gradually along the long axis of the ellipse.[6]

History

In 477 CE, prince Kashyapa seized the throne from King Dhatusena, following a coup assisted by Migara, the king’s nephew and army commander. Kashyapa, the king’s son by a non-royal consort, usurped the throne from the rightful heir, Moggallana, who fled to South India. Fearing an attack from Moggallana, Kashyapa moved the capital and his residence from the traditional capital of Anuradhapura to the more secure Sigiriya. During King Kashyapa’s reign (477 to 495), Sigiriya was developed into a complex city and fortress. Most of the elaborate constructions on the rock summit and around it, including defensive structures, palaces, and gardens, date back to this period.

Kashyapa was defeated in 495 by Moggallana, who moved the capital again to Anuradhapura. Sigiriya was then turned back into a Buddhist monastery, which lasted until the 13th or 14th century. After this period, no records are found on Sigiriya until the 16th and 17th centuries, when it was used as an outpost of the Kingdom of Kandy. When the kingdom ended, it was abandoned again.

The Mahavamsa, the ancient historical record of Sri Lanka, describes King Kashyapa as the son of King Dhatusena. Kashyapa murdered his father by walling him up alive and then usurping the throne which rightfully belonged to his brother Mogallana, Dhatusena’s son by the true queen. Mogallana fled to India to escape being assassinated by Kashyapa but vowed revenge. In India he raised an army with the intention of returning and retaking the throne of Sri Lanka which he considered to be rightfully his. Knowing the inevitable return of Mogallana, Kashyapa is said to have built his palace on the summit of Sigiriya as a fortress and pleasure palace. Mogallana finally arrived and declared war. During the battle Kashyapa’s armies abandoned him and he committed suicide by falling on his sword.

Chronicles and lore say that the battle-elephant on which Kashyapa was mounted changed course to take a strategic advantage, but the army misinterpreted the movement as the King having opted to retreat, prompting the army to abandon the king altogether. It is said that being too proud to surrender he took his dagger from his waistband, cut his throat, raised the dagger proudly, sheathed it, and fell dead. Moggallana returned the capital to Anuradapura, converting Sigiriya into a monastery complex.

Alternative stories have the primary builder of Sigiriya as King Dhatusena, with Kashyapa finishing the work in honour of his father. Still other stories have Kashyapa as a playboy king, with Sigiriya a pleasure palace. Even Kashyapa’s eventual fate is uncertain. In some versions he is assassinated by poison administered by a concubine; in others he cuts his own throat when isolated in his final battle.[7] Still further interpretations have the site as the work of a Buddhist community, with no military function at all. This site may have been important in the competition between the Mahayana and Theravada Buddhist traditions in ancient Sri Lanka.

The earliest evidence of human habitation at Sigiriya was found from the Aligala rock shelter to the east of Sigiriya rock, indicating that the area was occupied nearly five thousand years ago during the Mesolithic Period.

Buddhist monastic settlements were established in the western and northern slopes of the boulder-strewn hills surrounding the Sigiriya rock, during the 3rd century BC. Several rock shelters or caves were created during this period. These shelters were made under large boulders, with carved drip ledges around the cave mouths. Rock inscriptions are carved near the drip ledges on many of the shelters, recording the donation of the shelters to the Buddhist monastic order as residences. These were made within the period between the 3rd century BC and the 1st century CE.

Archaeological remains and features

In 1831 Major Jonathan Forbes of the 78th Highlanders of the British army, while returning on horseback from a trip to Pollonnuruwa, came across the „bush covered summit of Sigiriya”.[8] Sigiriya came to the attention of antiquarians and, later, archaeologists. Archaeological work at Sigiriya began on a small scale in the 1890s. H.C.P. Bell was the first archaeologist to conduct extensive research on Sigiriya. The Cultural Triangle Project, launched by the Government of Sri Lanka, focused its attention on Sigiriya in 1982. Archaeological work began on the entire city for the first time under this project. There was a sculpted lion’s head above the legs and paws flanking the entrance, but the head broke down many years ago.

Sigiriya consists of an ancient castle built by King Kasiappan during the 5th century. The Sigiriya site has the remains of an upper palace sited on the flat top of the rock, a mid-level terrace that includes the Lion Gate and the mirror wall with its frescoes, the lower palace that clings to the slopes below the rock, and the moats, walls, and gardens that extend for some hundreds of metres out from the base of the rock.

The site is both a palace and a fortress. Despite its age, the splendour of the palace still furnishes a stunning insight into the ingenuity and creativity of its builders. The upper palace on the top of the rock includes cisterns cut into the rock that still retain water. The moats and walls that surround the lower palace are still exquisitely beautiful.[9]

Site plan

Sigiriya is considered one of the most important urban planning sites of the first millennium, and the site plan is considered very elaborate and imaginative. The plan combined concepts of symmetry and asymmetry to intentionally interlock the man-made geometrical and natural forms of the surroundings. On the west side of the rock lies a park for the royals, laid out on a symmetrical plan; the park contains water-retaining structures, including sophisticated surface/subsurface hydraulic systems, some of which are working even today. The south contains a man-made reservoir; these were extensively used from the previous capital of the dry zone of Sri Lanka. Five gates were placed at entrances. The more elaborate western gate is thought to have been reserved for the royals.[10][11][12]

Frescoes

John Still in 1907 suggested, „The whole face of the hill appears to have been a gigantic picture gallery… the largest picture in the world perhaps”.[13] The paintings would have covered most of the western face of the rock, covering an area 140 metres long and 40 metres high. There are references in the graffiti to 500 ladies in these paintings. However, many more are lost forever, having been wiped out when the Palace once more became a monastery − so that they would not disturb meditation.[citation needed] Some more frescoes, different from the popular collection, can be seen elsewhere on the rock surface, for example on the surface of the location called the „Cobra Hood Cave”.

Although the frescoes are classified as in the Anuradhapura period, the painting style is considered unique;the line and style of application of the paintings differing from Anuradhapura paintings. The lines are painted in a form which enhances the sense of volume of the figures. The paint has been applied in sweeping strokes, using more pressure on one side, giving the effect of a deeper colour tone towards the edge. Other paintings of the Anuradhapura period contain similar approaches to painting, but do not have the sketchy lines of the Sigiriya style, having a distinct artists’ boundary line. The true identity of the ladies in these paintings still have not been confirmed. There are various ideas about their identity. Some believe that they are the wives of the king while some think that they are women taking part in religious observances. These pictures have a close resemblance to some of the paintings seen in the ajanta caves in India

The frescoes, depicting beautiful female figures in graceful contour or colour, point to the direction of the Kandy temple, sacred to the Sinhalese.

The Mirror Wall

Originally this wall was so well polished that the king could see himself whilst he walked alongside it. Made of a kind of porcelain, the wall is now partially covered with verses scribbled by visitors to the rock. Well preserved, the mirror wall has verses dating from the 8th century. People of all types wrote on the wall, on varying subjects such as love, irony, and experiences of all sorts. Further writing on the mirror wall has now been banned.

One such poem in Sinhala is:

The rough translation is: „I am Budal [the writer’s name]. (I) Came with all my family to see Sigiriya. Since all the others wrote poems, I did not!” He has left an important record that Sigiriya was visited by people beginning a very long time ago. Its beauty and majestic appearance made people stand in awe of the technology and skills required to build such a place

The gardens

The Gardens of the Sigiriya city are one of the most important aspects of the site, as it is among the oldest landscaped gardens in the world. The gardens are divided into three distinct but linked forms: water gardens, cave and boulder gardens, and terraced gardens.

The water gardens

The water gardens can be seen in the central section of the western precinct. Three principal gardens are found here. The first garden consists of a plot surrounded by water. It is connected to the main precinct using four causeways, with gateways placed at the head of each causeway. This garden is built according to an ancient garden form known as char bagh, and is one of the oldest surviving models of this form.

The second contains two long, deep pools set on either side of the path. Two shallow, serpentine streams lead to these pools. Fountains made of circular limestone plates are placed here. Underground water conduits supply water to these fountains which are still functional, especially during the rainy season. Two large islands are located on either side of the second water garden. Summer palaces are built on the flattened surfaces of these islands. Two more islands are located farther to the north and the south. These islands are built in a manner similar to the island in the first water garden.

The third garden is situated on a higher level than the other two. It contains a large, octagonal pool with a raised podium on its northeast corner. The large brick and stone wall of the citadel is on the eastern edge of this garden.

The water gardens are built symmetrically on an east-west axis. They are connected with the outer moat on the west and the large artificial lake to the south of the Sigiriya rock. All the pools are also interlinked using an underground conduit network fed by the lake, and connected to the moats. A miniature water garden is located to the west of the first water garden, consisting of several small pools and watercourses. This recently discovered smaller garden appears to have been built after the Kashyapan period, possibly between the 10th and 13th centuries.

The boulder gardens

The boulder gardens consist of several large boulders linked by winding pathways. The gardens extend from the northern slopes to the southern slopes of the hills at the foot of Sigiriya rock. Most of these boulders had a building or pavilion upon them; there are cuttings that were used as footings for brick walls and beams.

The terraced gardens

The terraced gardens are formed from the natural hill at the base of the Sigiriya rock. A series of terraces rises from the pathways of the boulder garden to the staircases on the rock. These have been created by the construction of brick walls, and are located in a roughly concentric plan around the rock. The path through the terraced gardens is formed by a limestone staircase. From this staircase, there is a covered path on the side of the rock, leading to the uppermost terrace where the lion staircase is situated.

Sigiriya: The Magic Mountain

by Manik Sandrasagra

|

|

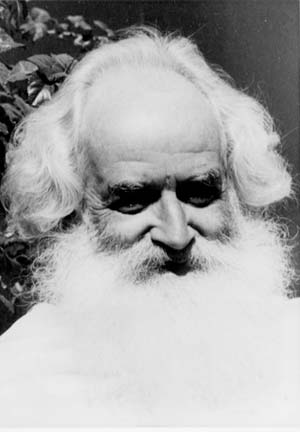

Swami Gauribala a.k.a German Swami

|

This paper is a free borrowing of ideas; from Ananda Coomarswamy and Rene Guenon as explained to me over several years (1971 to 1984) by the late Swami Gauribala also known as German Swami.

Swami Gauribala spent over 30 years studying Sihagiri, as he preferred to call it. At that time nobody was really interested, in what they called his 'theories’. Ever since Sihagiri was made a world heritage site, I have often been approached for Swami’s diaries and notebooks.

Not wanting to pander to the vanity of academics and researchers seeking fame, recognition and honour through their publications, I have on purpose withheld these valuable handwritten notebooks from public scrutiny.

Sacred is secret and Sihagiri does not need the patronage of academics or expensive publications for its continuity as a centre of initiation transcending the three worlds. As Swami once wrote to me, „The age-old mysteries and initiatic centres are still working and fully alive; the Guru-Shishya-Parampara still works inspite of all the corruptions and distortions of the anti-tradition”.

Saving Sihagiri for posterity and examining the few clues that it may occasionally throw up may mean work for archaeologists and researchers for several years, however unless they understand what they are dealing with, they will remain ignorant as to its essence and function. To them Sihagiri will remain a spectacular monument.

This article carries extracts from Swami Gauribala’s note-books. Swami wrote nothing original, everything quoted is either from Guenon, Coomaraswamy or some other sacred text..

„A son of two mothers,

he attains to kingship in his

discovery of knowledge,

he moves on the summit,

he dwells in his high foundation”.

– Rig Veda 1: 10: 2

|

|

Pabbata-raja made the mountain or rock his centre of ritual worship. The mountain at Mihintale, known in pre-Buddhist times as Missaka pabbata, and the rock at Sigiriya (above) were two of the main centres where pabbata-raja kings held their festivals, involving both rain-making and fertility.

|

The centre or fixed point is known symbolically to all traditional people everywhere as the 'pole’ or 'axis’ around which the world rotates. This idea has been depicted as a wheel in the Celtic, Chaldeon and Hindu traditions. The true significance of symbols like the Cross and the Swastika, seen worldwide from the far-east to the far-west is that they are intrinsically the 'Sign of the Pole’.

Centres rose in ancient times as a result of a science called sacred or sacerdotal geography through which precise laws determined the position of cities and temples. Between the foundation of a town and the development of a doctrine, or a new form of tradition arising through adaptation to conditions defined by the time and place, there was a certain relationship which resulted in the construction of the town symbolising the unfolding of the doctrine.

Naturally, the most meticulous precautions were taken when selecting the site of a town destined to become the metropolis or centre for a specified area of the world, so that the names of such towns merit careful study, as do the reported circumstances of their founding. Such centres existed in pre-Hellenic Crete, and it seems that there were several in Egypt, probably founded in successive epochs, like Memphis and Thebes.

The corresponding testimony of all traditions worldwide is that an archetypal 'Holy Land’ does exist; that it is the prototype for all other 'Holy Lands’, the spiritual centre to which all others are subordinate. The 'Holy Land’ is also the 'Land of the Saints’, the 'Land of the Blessed’, the 'Land of the Living’, and the 'Land of Immortality’.

The 'Holy Land’ in the present age, it is believed is defended by guardians who keep it hidden from profane view, while ensuring nevertheless a certain exterior communication, which to all intents and purposes is inaccessible and invisible to all except those possessing the necessary qualifications for entry.

Similar traditions concerning the earthly paradise are also well known, although little mentioned in public. In Islamic esotericism the 'green island’ (el jezirah el-Khadrah) and the 'white mountain’ (el jbabal el abiod) are well known. In the American traditions, 'Aztlan’ is symbolised by a white mountain, while in India, the 'white isle’ (shweta dweepa) is regarded as the 'Abode of the Blessed’, a name easily identifiable as the 'Land of the Living’.

Similar traditions concerning the earthly paradise are also well known, although little mentioned in public. In Islamic esotericism the 'green island’ (el jezirah el-Khadrah) and the 'white mountain’ (el jbabal el abiod) are well known. In the American traditions, 'Aztlan’ is symbolised by a white mountain, while in India, the 'white isle’ (shweta dweepa) is regarded as the 'Abode of the Blessed’, a name easily identifiable as the 'Land of the Living’.

The Celtic tradition describes a 'green isle’ as being the 'Isle of Saints’ or 'Isle of the Blessed’, in which at the centre stands the 'White Mountain’, with its summit purple, never submerged by any flood1. This 'Mountain of the Sun’ as it is also called, is the equivalent of Meru, also entitled 'White Mountain’. Meru is said to be encircled by a green belt, by the fact of it being situated in the middle of an ocean, and a triangle of light radiates at its peak.

Cosmas writing about Lanka from the reports of Sopater in 550 AD states as follows:

„The temples are numerous, and one in particular, situated on an eminence, is the great hyacinth2,as large as a pine-cone, the colour of fire, and flashing from a distance, especially when catching the beams of the sun – a matchless sight”.

„There are two Kings ruling at opposite ends of the island, one of whom possesses the hyacinth and the other the district, in which are the port and the emporium”.

The Hyacinth

Cosmas, and with the Chinese Hiuen Tsang, in the following century, a story emerges of a priceless red ruby which was fixed on the top of a pagoda in Central Lanka.

Hayton had also heard of the great red ruby: „The king of Celan hath the largest ruby in existence. When his coronation takes place this ruby is placed in his hand and he goes round the city on horse back holding it in his hand, and thenceforth all recognise and obey him as their king.”

Odoric too speaks of the great ruby and Kublai Khan’s endeavours to get it.

Ibn saw it in the possession of Ariya Chakravarti, a Tamil Chief ruling at Patlam.

Friar Jordanus speaks of two great rubies belonging to the King of Sylen, each so large that when grasped in the hand it projected a finger’s breadth at either side.

The fame, at least of these survived to the 16th Century for Andrea Corsali (1515) says: „They tell that the king of the island possesses two rubies of colour so brilliant and vivid that they look like the flame of fire.”

Sir Emerson Tennant, on the subject, quotes from a Chinese work a statement that early in the 14th Century the Emperor sent an officer to Ceylon to purchase a carbuncle of unusual lustre. This was fitted as a ball to the Emperor’s cap; it was upwards of an ounce in weight and cost 100,000 strings of cash. Everytime a great levee was held at night the red lustre filled the palace, and hence it was designated the red palace illuminator.”3

The other references to this spectacular ruby are those in the Travels of Sindbad the Sailor from the Arab epic work, Tales of Arabian Nights as well as the Travels of Marco Polo.

In and around 400AD Sihagiri was the centre of Sri Lankan culture and Kassapa was the king whose temple – palace was Sihagiri. Was then a red ruby on the summit of Sihagiri and was it a part of Kassapa’s regalia ?

The colour red represents the sun and all war gods. It is the masculine, active principle; fire, the sun, royalty, love, joy, festivity, passion, ardour, energy, ferocity, sexual excitement and blood lust. Also, according to Albertus Magnus (ca 1200-1280) stones such as the Hyacinth has the special power to disperse poison in air and vapour.

There are also other symbols in ancient traditions which represent the 'centre of the world’, one of the most remarkable and widely spread of which is that of Omphalos. In Greek the word signifies 'umbilical’, which in a general sense describes everything that is central, and in particular the hub of a wheel. The Sanskrit 'nabhi’ has the same connotations as do various words in the Germanic and Celtic languages derived from the same root, found in the forms 'nab’ and 'nav’.

Paradise

The Terrestrial Paradise possessed other names as well. It was called 'Paradesha’ which in Sanskrit means the 'Supreme Country’ which applies well to the spiritual centre par excellence, also called the 'Heart of the World’. It is from this word that the Chaldeons formed 'Pardes’ and westerners 'Paradise’. The Persian Alborj and Monsalvat of the Western Grail legend, the Arab mountain Qaf and the Greek Olympus all have the same meaning.

It can be clearly seen from the above that the idea of a spiritual centre – an island containing a 'sacred mountain’ which is also the axis mundi between heaven and earth is found in all traditions. For a while such a locality may have a tangible existence (even though not all 'holy lands’ were islands) however, there is also a symbolic meaning.

Historical facts, especially those pertaining to sacred history, translate in their own ways truths of a higher order owing to the law of correspondence which is the foundation of symbolism, and which unites all the words in total and universal harmony.

Considering the above, let us turn to Sihagiri and Lanka. Was Sihagiri designed as a city or could it have been much more ? Should not the origin myths of Lanka be considered when interpreting such important sites? Is it possible to understand the mind of spiritual man from our own materialistic perspective? Is it not better to leave things as they are without destroying the evidence? At present excavations are taking place without any clear basis, turning a vital part of our heritage into a giant western style 'theme park’.

Lanka

The very name Lanka means 'resplendent isle’ and in myth and legend and according to the oral tradition, it is 'Dhammadeepa’ the 'isle of the blessed’, where truth reigns. Every name given to Lanka has also a similar quality. Lakdiva, Serendib, Pomparippuwa, Ranbima, Tambapani, Sinhale, Eelam, Ceylon all suggest the same quality. We therefore live in a land that has been considered blessed from time immemorial.

In the centre of Lanka, like its heart stands a massive rock monolith first called Sihagiri and later Sigiriya. The original name can be loosely translated as 'Remembrance Rock’ and the latter as 'Lion Rock’. Around this rock, there are fourth century A.D. remnants of perhaps the most magnificent buildings Lanka can boast of.

AIthough now declared a 'World Heritage Site’, the written history of Lanka hardly describes the place. Even the name is only mentioned in four places in the Culavamsa, yet this is perhaps the most extensive edifice in Lanka. It is not impossible that the whole history of Sihagiri would have been different if a layman and not a Buddhist monk had been the author of the Culavamsa, a written history of Lanka.

This is the observation made by Wilhelm Geiger, the translator in his introduction to Part I of the Culavamsa. Continuing, Geiger stated that „Not what is said but what is unsaid is the besetting difficulty of Sinhalese history”. May I add that to a tantric siddha like Swami Gauribala, who understood the Mahayana doctrines very well, Sihagiri made complete sense, based on its design and context.

Was Sihagiri a symbol of the cosmos with seven levels representing the seven heavens of the planets? Was it a junction between heaven, earth and hell through which the axis mundi passes? Through contending viewpoints and perspectives in the oral and written history of Lanka a conflict emerged between orthodoxy and heterodox in relation to traditional kingship, where the ideal was divinity and the King was also its High Priest. This sense of divinity was linked to the idea of the King becoming Varuna, one of the ancient Indian gods.

Varuna

„As god of living waters, fertility and justice, and as a great king, Varuna belongs almost entirely to a settled order of things, to a city state and peasant culture of immemorial antiquity.

On the dark chthonic side of things, with its seasonal festivals, ritual eroticism, and possibly human sacrifice, the whole complex of ideas connected with Varuna and Aditi, Gandharvas and Apsaraas, etc. points backward to a great culture evolved with the beginnings of agriculture, and flourishing from the Mediterranean to the Indus, rather than to the priestly invention of later warlike peoples, such as the Persian or Indian Aryans. Varuna and Aditi in many respects suggest Tammuz and Ishthar.

The ideal of Kingship embodied in the original conception of Varuna may be said to have persisted in Indian culture up to the present day; it is very evident in the person of Rama. (Varuna changing into Prajapati, Purusa or Brahman, and Narayana or Vishnu. In the same way a succession of designations of the Great Mother and Earth Goddess can be recognised in Aditi, Ida, Dhisana, Prakrti, Vak and Laksmi and Bhumi Devi.) The ideal king is a Dharmaraja, an incarnation of justice, and the fertility and prosperity of the country depend upon the King’s virtue; the direct connection between justice and rainfall here involved is highly significant.

Most prominent in the personality of Varuna are his connection with the celestial (upper) waters, and with holy order (rta) physical and moral; his kingship and justice, and the fetters (pasa) with which he binds the sinner and controls the waters.

The description of Varuna in the Vishnudharmottara, III.52, though late, is not without interest and significance. He rides in a chariot drawn by seven hamsas, said to represent the Seven Seas, he has an umbrella of dominion, and is supported by a makara. He has somewhat of a hanging belly (a paunch (udara) for treasure); he is four-handed (a post-Vedic development), holding the lotus and fetter (pasa) in his right hands, conch and jewel-vessel (ratna-patra) in the left. His wife is Gauri (in the Ramayana, Gauri or Varuni), holding a blue lotus is her left hand. Attendants are Ganga on the right, holding a lotus and standing on a makara, and Yamuna on the left, holding a blue lotus and standing on a tortoise, said to represent time (kala).

It will be seen that Varuna’s original character as a great king, dispenser of justice and punisher of sin, lord of rivers and increase, is well preserved, and that the concrete symbolism is consistently and satisfactorily explained.”4

Sihagiri legend

(The history of Kassapa 1, who is associated with the Sihagiri legend is told in Chapters 38 and 39 of the Mahavamsa (Chulavamsa I and II).

Kassapa, brought up under Mahayana influence (Madhyamika and Prajnaparamita – Nagarjuna Ariya- deva: Bienlu, 13) dreams to become a cakravartin and rule from the central Mount Kailasa. He sacrifices his father for the sake of his ideal and tries to realise his dream by building the temple-palace at Sihagiri. By sacrificing Dhatusena he takes revenge for the killing of his guru by his father. Kassapa thus.

Kataragama

Let us digress for a moment to study Kataragama in southern Lanka. Here an unseen King represented by the colour red, rules from a royal palace with 505 courtiers in attendance following rituals instituted over 2000 years ago. Here lies the secret of traditional kingship where 'nobody’ was King and everybody equal. Fertility and continuity was the only reality. The visible King follows the divine original. As to what the divine design may be, it is left in the hands of the purohita, the royal priest.

In Lankan history in around the fourth century A.D., a conflict arose between King Dhatusena and his first-born son Kassapa. Dhatusena’s ideal of kingship differed from that of Kassapa. Kassapa followed the old path of 'the tortoise’ as symbolised in Kataragama, while Dhatusena was an adherent of a city culture based in Anuradhapura. Power was based on water and its use. The Kala Wewa was Dhatusena’s 'Gam Udawa’ and he paid a price for his reckless innovation.

Their conflict is a story of opposing viewpoints on what constitutes kingship, with Brahmins, Shamans and Priests on both sides fighting over definitions and ideals. Sihagiri was never the capital of Śrī Lanka. It was however, the symbol of Lankan kingship, with bringing rain in time being one of its main functions. It is also a mandala, wherein an ascent up to the summit was itself a ritual of purification. It was also the centre in which the 'Lion Race’ preserved its temperament. Masada in Israel is an interesting parallel.

When our own researchers have eyes to see and ears to hear, perhaps then and only then will Sihagiri reveal itself once more. Until then, what is truly sacred will remain a secret, academics and researchers notwithstanding with perhaps the exception of Raja de Silva, a former Commissioner of Archaeology.

We conclude by quoting the New Testament. Consider and compare the story of Kassapa with Galatians IV 22-31.

„The two sons of Abraham: the one by a bondmaid, born after the flesh (like Moggalana),

The other born by a freewoman, born after the Spirit (like Kassapa). But as then, he that was born after the flesh persecuted him that was born after the Spirit, even so it is now.

But if ye be led by the Spirit, ye are not under the Law”.

- Central Lanka has never been under water.

- Hyacinth (European): Prudence: peace of mind; heavenly aspiration. The blood of Hyacinthus, from which the hyacinth sprang when he was killed accidentally by Apollo, symbolizes vegetation scorched by the heat of the summer sun; but the flower springing from the blood represents resurrection in spring. Also the emblem of Cronos. (from An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols – J.C.Cooper – Thames and Hudson). The Hyacinth has also been identified as a Ruby by Richard W. Hughes (1996) in 'Ruby & Sapphire’

- IB IV, 174-175; Cathay p clxxvii; Hayton ch vi; Jord p 30; Ramus 1 180: Ceylon 1 – 568)

- Yaksas ll p26 (1928) Coomaraswamy „appears in a different light”, as a Priest-King or bodhisattva, enthroned on Mount Kailasa, the centre of the Holy Land, as the builder of the „most magnificent building of which Ceylon can boast”, as one of the greatest Kings of Lanka.

Palace in the sky or Mahayana Mandala?

Sigiriya and its Significance by Raja de Silva

[Bibliotheque (Pvt) Ltd. Sri Lanka] Rs. 3,000

|

| Tara is a goddess who was worshipped by Mahayana Buddhists in Sri Lanka. The divine females at Sigiriya are splendidly adorned with jewellary, bracelets, necklaces, tiaras, diadems, chaplets of flowers and are of three complexions red, yellow and green. The goddess Tara too has numerous manifestations in regal splendor and may be of red, yellow, green, blue or white complexion. |

|

by Tissa Devendra

It is rare pleasure to come across a book produced in Sri Lanka whose superb format and high quality illustrations are only surpassed by the richness of its contents. Raja de Silva has been one of our most distinguished Archaeological Commissioners who has, over and above the call of duty, devoted a lifetime of study to that most magnificent monument of Sinhala civilization – Sigiriya. His greatest contribution to Sigiriya, Sri Lanka’s cultural heritage and posterity was his meticulous restoration of the wonderful frescoes which had been brutally vandalised over forty years ago. This volume, his magnum opus, is the distillation of his painstaking research. He argues, with convincing cogency, that the traditional acceptance of this architectural wonder as the palace of Kassapa I, oft- damned as the „parricide king”, is based on the shifting sands of biassed chronicles, unsupportable theories and romantic imagination.

The author’s argument is simply stated. Sigiriya was not Kassapa’s palace and pleasure garden. Neither was it a fortress nor was it ever the capital city of Sri Lanka. What this site encompasses is a vast Buddhist monastic complex, embracing both Theravada and Mahayana practices, and spanning many centuries -long before and long after Kassapa’s reign. De Silva’s conclusions are based on an impressive analysis of data drawn from many disciplines – epigraphy, literature, meteorology, Buddhist philosophy, iconography, art history, chemistry and, above all, over a century of scientific excavation by the Archaeological Department. No other study has ever drawn on such a rich lode of material and few, if any, have been able to match de Silva’s great erudition, practical experience and his „magnificent obsession” with the subject of Sigiriya and its significance.

Significant Findings

Some of his most significant conclusions are disarming in their simplicity. No remains of tiles, rafters or post- holes [for pillars] have ever been discovered on Sigiriya’s summit. Furthermore, from a study of monsoon patterns and wind velocity, buttressed by H. C. P. Bell’s excavation reports, he draws two conclusions. The first is that Kassapa’s eighteen year reign would have given him only six months per year during which any construction work was possible on the summit. In this brief ‘window of time’ it was logistically impossible for Kassapa to marshall the men and materials, apart from an ‘army’ of superb artists clinging to precarious perches, to build a ‘palace in the clouds’. De Silva argues, most convincingly, that the summit was a complex of ‘kutis’ [cells] where Buddhist monks lived in meditation and contemplation, far above the hustle and bustle of mundane life. The ‘asanas’ were seats for meditation, discourses and doctrinal disputation. The paved walkways were for meditative perambulation, a feature unique to the Buddhist monastic tradition. The ponds and gardens were designed for contemplation, a Mahayana concept now widely known because of the rock and sand garden of the wonderful Zen temple in Kyoto. A stupa on the summit, to which little attention has been paid, completes the monastery complex. No other monastic site in this country seems more appropriate for seeking the ‘divine emptiness’ of Nirvana or reincarnation as a Bodhisattva, in the Mahayana tradition.

The author’s disarmingly simple explanation for the lack of evidence of permanent roofs on the summit further buttresses his contention that this was a monastery and no palace. He argues that the roofs of the kutis’ [monks cells] were thatched in cadjan – the only type of roof readily renewable after the battering of monsoons. Furthermore, this would place these cells firmly in the Buddhist tradition of ‘pannasalas’ [leaf huts] as dwellings of monks. Interestingly enough, the plausibility of de Silva’s conclusion is now backed up by a parallel from another continent, another hemisphere and another century. In 1450 or so the Incas of Peru built the mountain city of Machu Picchu 1,500 feet high up in the Andes. It has been described in terms that apply equally to Sigiriya. „The Cyclopean size of its stone blocks and the masterful way they were fitted together seem like an unbelievable dream”. Scholars agree that while the stone walls remain intact no ruins of any roofs remain because they were thatch – easily renewable after the fierce gales that sweep the Andes!

History and the Culavamsa

Central to the author’s thesis is the archaeological evidence he adduces to establish that Sigiriya and its environs were the location of monastic establishments from before Kassapa’s reign until the 12th century. For much of this period it was the abode of monks who were followers of the Abhayagiri Vihara which was the fount of Mahayana doctrines in Sri Lanka. It is for this reason that the author is, rather too harshly, critical of the Culavamsa account of Kassapa’s reign atop Sigiriya. By the 12th century, when Ven. Dhammakitti wrote this chronicle Mahayana worship had long been wiped out and the Theravada orthodoxy of Mahavihara had regained the supremacy it yet enjoys.

It was only natural for a Mahavihara writer to look at the past from that particular perspective. I, for one, cannot believe that Ven. Dhammakitti fantasised or wrote of Kassapa with malice aforethought. History, after all, is the victor’s version. If the battle of Waterloo was won by Napoleon his scholars would have written a very different history of Europe from that which we studied. As such, one cannot expect a Mahavihara monk to be scientific and objective about a perceived patron of a ‘heretical’ establishment.

Mahayana and Tara Devi

De Silva has opened a much needed window into the wide spread, vitality and monumental contribution of Mahayana to Sri Lanka’s cultural history. This ‘secret history’, which has left its magnificent sculptures ranging from Weligama to Buduruwegala and even Aukana, needs both deep study and popular discourse to achieve acceptance as an integral component of our history. The greatest Mahayana monument in Sri Lanka, according to the writer’s almost watertight interpretation, is Sigiriya. The entire complex has been conceived as one integrated whole – a Mahayana ‘mandala’ a symbolic diagram of the meditative process to attain Bodhisattva-hood. The way to the summit leads through gardens, ambulatory paths, ponds and fountains – all objects of contemplation — which are surrounded by scattered monastic cells and caves. The Lion Stairway, according to Buddhist iconography, was „to remind the devotee whose of the Buddha whose voice was like that of a roaring lion [Mahasihanada] enunciating the Truth”.

The lion also symbolises Tara the female Bodhisattva of Mahayana Buddhism to whose adoration the incomparable frescoes are dedicated. Every single figure exemplifies a different aspect of Tara. This repetition of the object of ‘worship’ is characteristic of a Mahayana technique of meditation and is most famously seen in the Tun Huang ‘Cave of a Thousand Buddhas’. Sadly, a thousand cruel monsoons have lost us a place in the sun for Sigiriya as the „Mountain of a Thousand Taras”. But thanks to Raja de Silva we now see the wondrous Tara, once again, in her true aspect as Bodhisattva. I dare say no more about the frescoes, or Sigiriya, – the author has said it all with great erudition and fine sensitivity.

Postscript

Raja de Silva’s „Sigiriya and its Significance” was formally launched, with singular felicity, at Hotel Sigiriya on Saturday 26 October. The hotel management had generously hosted an interesting mix of people to the occasion – journalists, artists, dilettante scholars, bird-watchers and even a swami [of sorts]. We sat facing the western face of Sigiriya rose-hued and mysterious in the rays of the setting sun. Raja de Silva modestly sketched out his theory and adroitly fielded a variety of questions ranging from his doubts about the Culavamsa ‘history’, the vital statistics of the frescoed ladies and the libidinous nature of Tantrayana practices. Raja put in a bravura performance and, what is most important, threw out a challenge to our historians, archaeologists and scholars to engage in an open discussion of his thesis, which they have never commented on in spite of its earlier publication in scholarly journals. We look forward to a battle of minds.

In concluding this review I quote from two poems that encapsulate Sigiriya’s enduring romance and mystery. The first is Verse 261 of the Graffiti [trans. Reynolds]

Who is not happy when he sees

Those rosy palms, rounded shoulders

Gold necklaces, copper-hued lips

And long long eyes.

The next is from the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda [who spent some years in ‘Ceylon’] writing of Machu Picchu in phrases redolent of Sigiriya:

Tall city of stepped stone

High reef of the human dawn…

The fallen kingdom survives us all this while.

więcej na http://sigiriya.org/

Polonnaruwa

– zabytkowe miasto w Sri Lance. Po zniszczeniu Anuradhapury w 993 n.e. przez władcę hinduskiego Rajaraja Chola I dotychczasowa okresowa rezydencja królewska została przekształcona w stolicę. Zbudowano obiekty religii hinduistycznej, w tym świątynię boga Sziwy. Odzyskanie Cejlonu przez króla Vikkamabahu (znanego też jako Kassapa VI) nie tylko nie pozbawiło Polonnaruwy funkcji stołecznych, ale została ona zabudowana dodatkowo świątyniami buddyjskimi, z których najważniejsza była Hatadage (Świątynia Zęba Buddy). Największy rozkwit osiągnęła Polonnaruwa w okresie panowania króla Parâkramabâhu I Wielkiego w latach 1153-1186. Stworzył on otoczone potrójnym murem bajkowe miasto-ogród, w którym pałace i świątynie były wtopione w krajobraz. Z okresu jego panowania pochodzi także Lankatilaka, potężna ceglana budowla z zachowanym wielkim posągiem Buddy oraz Gal Vihara, klasztor z zespołem wielkich rzeźb skalnych. Jeden z jego następców, król Nissanka Malla, zbudował jeszcze jedną imponującą budowlę – Rankot Vihara, jest to stupa o średnicy 175 m i o wysokości 55 m. W późniejszym okresie miasto było często najeżdżane przez sąsiadów, funkcję stolicy pełniło jeszcze okresowo w XIII wieku.

Ważniejsze zabytki

- Ruiny pałacu królewskiego

- właściwy pałac o wymiarach 13 na 31 metrów o ścianach grubości 3 metrów;

- sala audiencyjna (sala posiedzeń Rady Królewskiej);

- basen;

- Zespół świątyń, tzw. czworokąt świątynny

- Vatadage, „Okrągła Świątynia” o średnicy około 18 m, z czterema wejściami i umieszczoną centralnie małą stupą mieszczącą cztery posągi siedzącego Buddy;

- Hatadage, świątynia, w której przechowywano relikwię zęba Buddy;

- Thuparama, najlepiej zachowana świątynia w Polonnaruwie, z ceglanym dachem;

- Latha Mandapaya, mała stupa otoczona kamiennymi kolumnami i obwiedziona wyciętą z kamienia balustradą naśladującą drewno;

- Gal Pota, czyli „kamienna książka”, blok kamienny z inskrypcjami;

- Satmahal Prasada, sześciopoziomowa budowla w kształcie pagody;

- Lankatilaka, potężna ceglana budowla z zachowanym wielkim posągiem Buddy;

- Gal Vihara, świątynia skalna, zespół czterech rzeźb w ścianie skalnej wyobrażających Buddę;

- Rankot Vihara, monumentalna stupa o średnicy 175 m i o wysokości 55 m.

Polonnaruwa ( Tamil – பொலநறுவை or புளத்தி நகரம் as called by Cholas) is a town. It’s the main town of Polonnaruwa District in the North Central Province, Sri Lanka. Kaduruwela area is the Polonnaruwa New Town and the other part of Polonnaruwa, remains as the royal ancient city of polonnaru kingdom.

The second most ancient of Sri Lanka’s kingdoms, Polonnaruwa was first declared the capital city by King Vijayabahu I, who defeated the Chola invaders in 1070 to reunite the country once more under a local leader.

History

While Vijayabahu’s victory and shifting of kingdoms to the more strategic Polonnaruwa is considered significant, the real „Hero of Polonnaruwa” of the history books is actually his grandson, Parakramabahu I. It was his reign that is considered the Golden Age of Polonnaruwa, when trade and agriculture flourished under the patronage of the king, who was so adamant that no drop of water falling from the heavens was to be wasted, and each was to be used toward the development of the land; hence, irrigation systems that are far superior to those of the Anuradhapura Age were constructed during Parakramabahu’s reign, systems which to this day supply the water necessary for paddy cultivation during the scorching dry season in the east of the country. The greatest of these systems, is the Parakrama Samudraya or the Sea of Parakrama. It is of such a width that it is impossible to stand upon one shore and view the other side, and it encircles the main city like a ribbon, being both a moat against intruders and the lifeline of the people in times of peace. The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was completely self-sufficient during King Parakramabahu’s reign.

With the exception of his immediate successor, Nissankamalla I, all other monarchs of Polonnaruwa were slightly weak-willed and rather prone to picking fights within their own court.

They also went on to form more intimate matrimonial alliances with stronger South Indian kingdoms, until these matrimonial links superseded the local royal lineage and gave rise to the Kalinga invasion by King Kalinga Magha in 1214 and the eventual passing of power into the hands of a Pandyan King following the Arya Chakrawarthi invasion of Sri Lanka in 1284. The capital was then moved to Dambadeniya.

They also went on to form more intimate matrimonial alliances with stronger South Indian kingdoms, until these matrimonial links superseded the local royal lineage and gave rise to the Kalinga invasion by King Kalinga Magha in 1214 and the eventual passing of power into the hands of a Pandyan King following the Arya Chakrawarthi invasion of Sri Lanka in 1284. The capital was then moved to Dambadeniya.

The city of Polonnaruwa was also called Jananathamangalam during the short Chola reign.

Present day

Present day

Today the ancient city of Polonnaruwa remains one of the best planned archaeological relic sites in the country, standing testimony to the discipline and greatness of the Kingdom’s first rulers. Its beauty was also used as a backdrop to filmed scenes for the Duran Duran music video Save a Prayer in 1982. The ancient city of Polonnaruwa has been declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO.

Near the ancient city, there is a small town with several hotels (especially for tourists) and some glossy shops, and places to fulfill day-to-day needs. There are government institutions in a newly built area called “new town,” about 6 km away from the town and the main road. The largest school in the district, Polonnaruwa Royal Central College is situated at new town.

Polonnaruwa is the second largest city in North Central Province, but it is known as one of the cleanest and more beautiful cities in the country. The green environment, amazing ancient constructions, Parakrama Samudraya (a huge lake built in 1200), and attractive tourist hotels and hospitable people, attract tourists.

Climate

One recent scientific observation is that of its climate changes: historically, Polonnaruwa had a tropical climate most of the year, although it was occasionally chilly in December and January. But in recent years the rain and chilliness has been increased noticeably. Although this is surprising to some people, it is more enjoyable for tourists. However, there is a setback, as paddy field farmers can suffer when there is too much rain.

(Powiększ) – te motywy wyraźnie nawiązują zwierzęcych i roślinnych motywów znanych ze złotych wyrobów scytyjskich

(Powiększ) – te motywy wyraźnie nawiązują zwierzęcych i roślinnych motywów znanych ze złotych wyrobów scytyjskich

Kilka obrazów przyrody z Siel-Lanki

kwiaty

Typowe drzewa owocowe na Siel-Lance

Typowe drzewa owocowe na Siel-Lance

Roślinność wodna – nie tylko lotosy

Roślinność wodna – nie tylko lotosy

Czasami prawdziwa wodna dżungla

Czasami prawdziwa wodna dżungla

Pęd jadalnej paproci – jadalny tylko gdy zwinięty w pąk

Pęd jadalnej paproci – jadalny tylko gdy zwinięty w pąk

Zbiór herbaty na wyżynach – więcej o herbacie przy okazji kiedy napiszemy o owocach i jedzeniu- w dziale Kuchnia Królestwa SIS

Zbiór herbaty na wyżynach – więcej o herbacie przy okazji kiedy napiszemy o owocach i jedzeniu- w dziale Kuchnia Królestwa SIS

Na koniec banalnie ale pięknie

Na koniec banalnie ale pięknie

Bo dalej były już bardzo piękne sjeliańskie Małe Dewy (Divy) czyli Malediwy – czyli dalszy ciąg SielLanki, jeszcze bardziej banalny niż kwiat powyżej

Bo dalej były już bardzo piękne sjeliańskie Małe Dewy (Divy) czyli Malediwy – czyli dalszy ciąg SielLanki, jeszcze bardziej banalny niż kwiat powyżej

Z jednym wyjątkiem – tutaj, a Małych Dewach, też słyszeli o Euro 2012

Z jednym wyjątkiem – tutaj, a Małych Dewach, też słyszeli o Euro 2012

Do przyrody, roślinności, jedzenia i innych spraw związanych ze wspólnotą języka phali , sanskrytu i polskiego oraz w ogóle języków słowiańskich jeszcze wrócimy – widać że jest o czym pisać i mówić – chociażby dzięki dobrze znanemu nam w Polsce słowu Sielanka, które – możemy zapewnić solennie wszelkich sceptyków – nie wzięło się jako „pożyczka etymologiczna” z Niemiec, Grecji, Rzymu, Persji ani nie jest pożyczką polską z japońskiego.