How grain came to Sumer

Goran Pavlovic © © Czesław Białczyński (tłumaczenie)

How grain came to Sumer

Skąd zboże przywędrowało do Sumeru

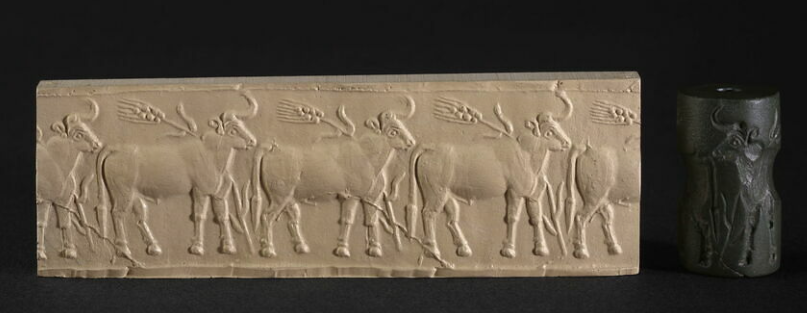

Sumerian cylinder seal, Uruk, c. 3500-3100BC , currently in Louvre

Sumeryjska pieczęć cylindryczna, Uruk, ok. 1930 r. 3500-3100BC, obecnie w Luwrze

Description: cattle herd in a grain field…Now unless Sumerians grew giant grains, this is most likely a symbol, of something, but what?

Opis: stado bydła na polu zbożowym… O ile Sumerowie nie uprawiali gigantycznych rozmiarów zbóż, jest to najprawdopodobniej symbol czegoś, ale czego?

Well, as I already explained in my post „Bulls and grain bowls„, this is a calendar marker for the grain harvest which in Mesopotamia starts in Apr/May, Taurus

Cóż, jak już wyjaśniłem w moim poście „Byki i kadzie na zboże”, jest to znacznik kalendarza zbiorów zbóż, które w Mezopotamii zaczynają się w kwietniu/maju, Byk /Tur (Taurus)

Taurus, which is an ancient animal calendar marker which marks the beginning of the calving season of the wild Eurasian cattle, which used to start in Apr/May…

Byk /Tur, który jest starożytnym znacznikiem kalendarza zwierząt, który wyznacza początek sezonu wycielenia dzikiego bydła euroazjatyckiego, który rozpoczynał się w kwietniu/maju…

And has nothing to do with stars…I talked about this in my post „Dairy farming seal„…

I nie ma nic wspólnego z gwiazdami… Mówiłem o tym w moim poście ” Pieczęć hodowli bydła mlecznego”… [Nie powstał i nie został tak nazwany z odczytywania symbolicznych konstelacji gwiazd Nieba, ale przyrody Ziemi. CB]

Keeping that in mind, let’s have a look at another interesting cylinder seal from Uruk, dated to 3200BC, also in Louvre. Description: king-priest and his acolyte feeding the sacred herd…

Mając to na uwadze, spójrzmy na kolejną interesującą pieczęć cylindryczną z Uruk, datowaną na 3200 r p.n.e., również w Luwrze. Opis: król-kapłan i jego akolita karmią święte stado…

You can see that the king is feeding the calves…So again we are in Taurus, the calving season…But what is the king feeding the calves with? It’s hard to see on this impression.

Widać, że król karmi cielęta… Więc znowu jesteśmy w Byku, w okresie porodów… Ale czym król karmi cielęta? Trudno dostrzec na tej impresyjnej płaskorzeźbie.

Here is another depiction of the same scene. And here it is pretty clear that the king-priest’s acolyte is holding the same giant grain…Which is then what the king is feeding the calves with…

Oto kolejny obraz tej samej sceny. I tutaj jest całkiem jasne, że akolita króla-kapłana trzyma ten sam gigantyczny kłos zboża… Czym więc król karmi cielęta…

So again, unless Sumerians grew giant grains, this is also a symbol, of the same thing: We harvest grain at the same time the wild Eurasian cattle calve…

Więc znowu, jeśli Sumerowie nie uprawiali gigantycznych zbóż, jest to również symbol tego samego: zbieramy zboże w tym samym czasie, co dzikie bydło euroazjatyckie się cieli…

And maybe Sumerians had some kind of thanksgiving ritual, where they fed the first calves with first grain? Don’t know…

A może Sumerowie mieli jakiś rytuał dziękczynny, w którym karmili pierwsze cielęta pierwszymi kłosami dojrzałego zboża? Nie wiem…

But I have already talked about all this before…So today I would like to talk about something else: How old are some of the Sumerian legends? For instance this one: „How grain came to Sumer„…

Ale już o tym wszystkim mówiłem… Więc dzisiaj chciałbym porozmawiać o czymś innym: Ile lat mają niektóre z sumeryjskich mitów? Na przykład ten: „Jak zboże przybyło do Sumeru”…

In this legend, we can read that:

W tej legendzie możemy przeczytać, że:

„Men used to eat grass with their mouths like sheep. In those times, they did not know grain, barley or flax”

„Mężczyźni jedli trawę wkładając ją w usta jak owce, które rwą ją zębami i mielą w pysku. W tamtych czasach nie znali zboża, jęczmienia ani lnu”

When was this time „before grain” in Mesopotamia?

Kiedy zatem to było – „przed czasami uprawy zboża” w Mezopotamii?

„An brought these down from the interior of heaven”

„Sprowadził je z wnętrza nieba”

What does this mean „the interior of heaven”?

Co to znaczy „wnętrze nieba”?

Look at this:

Spójrz na to:

Sumerian: kur: n., mountain; highland; (foreign) land; the netherworld…

Sumeryjski: kur: n., góra; wyżyna; (obca) ziemia; zaświaty…

Sumerian Ekur (𒂍𒆳 É.KUR), is a term meaning „mountain house”. The term was applied specifically to the mountain(s), where the gods were born…

Sumeryjski Ekur (𒂍𒆳 É.KUR) to termin oznaczający „dom górski”. Termin ten został zastosowany konkretnie do gór, w których urodzili się bogowie…

And before the later speculative view was developed, according to which the gods, or most of them, have their seats in heaven, it was on the E.KUR mountain(s) where gods dwelt…

I zanim rozwinął się późniejszy pogląd spekulacyjny, zgodnie z którym bogowie, lub większość z nich, ma swoje miejsca w niebie, to właśnie na górach E.KUR mieszkali bogowie…

So maybe An didn’t bring the grain from „the interior of heaven” but from the mountains…

Może więc An nie przywiózł ziarna z „wnętrza nieba”, ale z gór…

E.KUR (The mountain house) was thus the place of the Assembly of the gods in the „Garden of the gods”. Which is why E.KUR was also the name for Ziggurats, which were supposed to be models, imitations of the real, one and only E.KUR…

E.KUR (Dom górski) był więc miejscem Zgromadzenia Bogów w „Ogrodzie Bogów”. Dlatego E.KUR to także nazwa Zigguratów, które miały być modelami, imitacjami prawdziwego, jedynego E.KUR…

„Enlil…looked southwards and saw the wide sea; he looked northwards and saw the mountain of aromatic cedars. Enlil piled up the barley, gave it to the mountain…”

„Enlil… spojrzał na południe i ujrzał szerokie morze; spojrzał na północ i ujrzał górę w aromatycznych cedrach. Enlil zebrał jęczmień, dał go górze…”

„Then Ninazu said: „Let us go to the mountain, to the mountain where barley and flax grow; …… the rolling river, where the water wells up from the earth. Let us fetch the barley down from its mountain, let us introduce the barley into Sumer…”

„Wtedy Ninazu powiedział: „Chodźmy w góry, na górę gdzie rośnie jęczmień i len; …… gdzie toczy swe wody rzeka, gdzie źródło tryska z ziemi. Sprowadźmy jęczmień z jego [Enlila – CB] góry i wprowadźmy jęczmień do Sumeru…”

Very very interesting…Because that is exactly what happened…around 9000BC…

Bardzo, bardzo interesujące… Ponieważ tak się właśnie stało… około 9000 lat p.n.e….

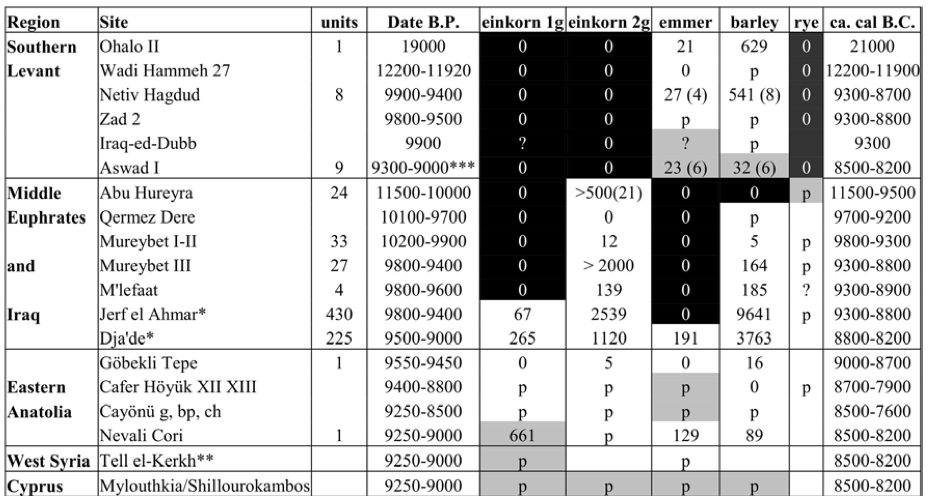

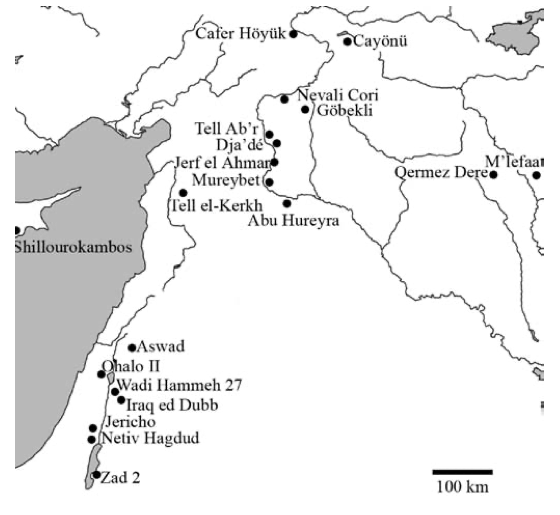

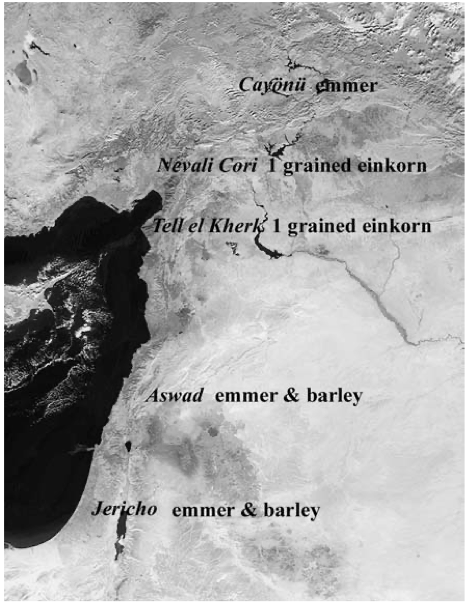

Today I came across this article: „The distribution, natural habitats and availability of wild cereals in relation to their domestication in the Near East: multiple events, multiple centres” which compares the late Pleistocene/early Holocene archaeobotanical assemblages found in the Near East with present-day distributions of wild cereals…

Dzisiaj natknąłem się na artykuł: „Rozmieszczenie, siedlisk przyrodniczych i dostępność dzikich zbóż w odniesieniu do ich udomowienia na Bliskim Wschodzie: wiele wydarzeń, wiele ośrodków”, który porównuje późnoplejstoceńskie/wczesnoholoceńskie zbiorowiska archeobotaniczne znalezione na Bliskim Wschodzie z dzisiejszą dystrybucją dzikich zbóż…

The early agricultural sites are found in the same areas where the wild grains grow in abundance even today. In the mountains and highlands surrounding (and mainly to the north of) Mesopotamia…Look at the relief of the early cereal domestication sites…

Remember my article about the Garden of eden? You know the garden of the God(s)…Which was located „on the holy mountain”…Where, it turns out, grains grew wild in huge amounts…

Pamiętasz mój artykuł o Ogrodzie Eden? Znasz Ogród Boga(ów)… Który znajdował się „na świętej górze”… Gdzie, jak się okazuje, dzikie zboża rosły w ogromnych ilościach…

Is this the place where during „Golden age humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labor”? You know, Eden…The place from which 4 rivers emerge…The mountains north of Sumer…

Apart from wild cereals, these uplands are full of edible trees: sweet oaks, hazels, fir, junipers…The true garden of eden: God said, “Let the land produce vegetation: seed-bearing plants and trees on the land that bear fruit with seed in it, according to their various kinds”

Oprócz dzikich zbóż, te wyżyny pełne są jadalnych drzew: słodkich dębów, leszczyny, jodły, jałowców… Prawdziwy ogród Eden: Bóg powiedział: „Niech ziemia wyda roślinność: rośliny nasienne i drzewa na ziemi, która przynosić będą owoce z nasieniem, według swoich różnych rodzajów”

I wrote series of articles about human relationship with oaks and human consumption of acorns. It seems that all the earliest permanently settled sites were located in edible acorn rich areas. The jump page to the acorn related articles is called 🙂 „Acorns”

Napisałem serię artykułów o związkach człowieka z dębami i spożywaniu przez człowieka żołędzi. Wydaje się, że wszystkie najwcześniejsze miejsca osiedlenia na stałe znajdowały się na obszarach bogatych w jadalne żołędzie. Strona przechodnia do artykułów związanych z żołędziami nazywa się 🙂 „Żołędzie”

Oak uplands can easily support large villages of up to 1000 people and these people could harvest in 3 weeks enough acorns to last them 2 to 3 years…

Wyżyny dębowe mogą z łatwością obsłużyć duże wioski do 1000 osób, a ludzie ci mogą zebrać w ciągu 3 tygodni wystarczającą ilość żołędzi na 2-3 lata…

Acorns could be stored in above ground aerated bins, in underground pits or they can be buried at the edge of streams where they can get leached while they keep fresh…

Żołędzie można przechowywać w naziemnych pojemnikach napowietrzanych, w podziemnych dołach lub zakopać je na skraju strumieni, gdzie mogą zostać wypłukane, zachowując świeżość…

The people of these oak cultures could, with very little effort, provide their daily bread doing what god told them to do: eat the fruit of the trees and plants that bear seeds…

Ludzie z tych kultur dębowych mogli, przy niewielkim wysiłku, dostarczać chleba powszedniego, robiąc to, co kazał im Bóg: jeść owoce z drzew i roślin, które rodzą nasiona…

With plenty of free time people could enjoy life and develop their culture and technology. With plentiful supply of food there was no need to kill and eat all the animals that were caught…

Dzięki dużej ilości wolnego czasu ludzie mogli cieszyć się życiem, rozwijać swoją kulturę i technologię. Przy obfitych zapasach żywności nie było potrzeby zabijania i zjadania wszystkich schwytanych zwierząt…

So people could catch and keep the animals, breed them and eventually domesticate them. It was these animals that were probably first fed the wild grasses which later became our grains…

Więc ludzie mogli łapać i trzymać zwierzęta, hodować je i ostatecznie oswajać. To właśnie te zwierzęta były prawdopodobnie pierwszymi karmionymi dzikimi trawami, które później stały się naszymi zbożami…

Interesting, right?

Ciekawe prawda?

Garden of the gods? So how old is the Sumerian legend about „How grain came to Sumer”? Old, very old…

Ogród Bogów? Ile lat ma zatem sumeryjski mit o tym, jak zboże przybyło do Sumeru? Jest stary, bardzo stary…

Guess what, there could be one even older legend. Found in Europe…But possibly not originating in Europe…

Zgadnij gdzie istniała jeszcze jedna, starsza legenda. Znaleziono ją w Europie… Ale możliwe że nie pochodzi ona z Europy…

Before people gathered and processed grain, they gathered and processed acorns…

Zanim ludzie zbierali i przetwarzali zboże, zbierali i obrabiali żołędzie…

Sooooo???

Taaaaaak???

Have you ever heard about the legend how Pelasgos taught people how to eat acorns?

Czy słyszałeś kiedyś o micie, w którym Pelasgos uczy ludzi jeść żołędzie?

Apparently: „…Pelasgos was he who checked the habit of eating green leaves, grasses, and roots always inedible and sometimes poisonous. But he introduced as food the nuts of trees, not those of all trees but only the acorns of the edible oak…”

Podobno: „…Pelasgos był tym, który wstrzymał jedzenie zielonych liści, traw i korzeni, zawsze niejadalnych, a czasem trujących, a wprowadził jako pokarm orzechy drzew, nie wszystkich drzew, ale tylko żołędzie, jadalne z dębu…”

I talked about this in my posts „Pelasgos” and „Acorns in ancient texts„…

Mówiłem o tym w moich postach „Pelasgos” i „Żołędzie w starożytnych tekstach”…

So how old is this myth? And where did it originate? Lots of things to ponder…

That’s it for tonight…

Więc ile lat ma ten mit? I skąd oryginalnie pochodzi? Wiele rzeczy do przemyślenia…

To tyle na dzisiaj…

źródło: https://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2021/10/how-grain-came-to-sumer.html?m=1