Calendar (Kalendarz)

©by Goran Pavlovic © tłumaczenie Czesław Białczyński

In the mountains of the Balkans, up until the end of the 20th century, shepherds carried with them a calendar stick. It was a stick with a notch cut into it for every day of the year and a cross or some other symbol for major holy days, which in Serbia are all linked to major agricultural events and major solar cycle events. At the end of every day a piece of the stick up to the first notch, representing the previous day, was cut off from the stick. When the last piece was cut, the year was over. This was a very effective way to track the passage of time. It was simple and could have been used easily by uneducated shepherds in the mountains where they were often cut off from the rest of the population for up to nine months. By looking at the stick they would know when it is time to praise god and their protector saint. But also the would know when the cheese needs to be ready and packed so that it can be sent from the mountain stations down to the valleys. And when to gather the flocks for sheering and when to start migrating down to the valleys before the winter descends.

W górach na Bałkanach do końca XX wieku pasterze nosili ze sobą kalendarz. Był to patyk z wycięciem na każdy dzień roku i krzyżem lub innym symbolem ważnych dni świątecznych, które w Serbii są związane z ważnymi wydarzeniami rolniczymi i ważnymi wydarzeniami związanymi z cyklem słonecznym. Na koniec każdego dnia odcinano z patyka kawałek do pierwszego nacięcia, reprezentujący dzień poprzedni. Kiedy ostatni kawałek został odcięty, rok się skończył. Był to bardzo skuteczny sposób śledzenia upływu czasu. Był prosty i mógł być z łatwością używany przez niewykształconych pasterzy w górach, gdzie często byli odcięci od reszty populacji nawet na dziewięć miesięcy. Patrząc na patyk wiedzieliby, kiedy nadszedł czas, aby chwalić Boga i swojego świętego opiekuna. Ale także wiedzieliby, kiedy ser musi być gotowy i zapakowany, aby można go było wysłać z górskich stacji w doliny. A kiedy zbierać stada do strzyżenia i kiedy rozpocząć migrację w doliny, zanim nadejdzie zima.

Two shepherds minding flocks on the mountain would be able to coordinate their actions with each other and with the people from the valleys by using identical calendar sticks.

Dwóch pasterzy pilnujących stad na górze mogłoby koordynować swoje działania między sobą oraz z mieszkańcami dolin za pomocą identycznych kalendarzy.

But in order to make these calendar sticks, you need to know:

Ale aby zrobić te kalendarze, musisz wiedzieć:

1. When does the solar year start?

2. How many full moons there are in a year?

3. How many days there are in a moon?

4. How many full moons are in a solar year?

5. How many full extra days there are after the end of the last full moon before the beginning of the new solar year?

1. Kiedy zaczyna się rok słoneczny?

2. Ile jest pełni księżyca w ciągu roku?

3. Ile dni ma księżyc?

4. Ile pełnych księżyców przypada na rok słoneczny?

5. Ile pełnych dodatkowych dni jest po zakończeniu ostatniej pełni księżyca przed początkiem nowego roku słonecznego?

Once you know this, you can make a stick calendar, give it to people and they will be able to coordinate their actions. Here is an example of the stick calendar from Bulgaria.

Gdy już to wiesz, możesz zrobić kalendarz sztyftowy, dać go ludziom, a oni będą mogli koordynować swoje działania. Oto przykład kalendarza sztyftowego z Bułgarii.

How do you determine all the above? By a very long period of observation of the sun and the moon and their changes, and by realizing that they follow cyclical patterns. Then you need to determine what these cycles are and how they relate to each other.

Jak ustalić wszystkie powyższe znaki? Przez bardzo długi okres obserwacji Słońca i Księżyca i ich zmian oraz przez uświadomienie sobie, że podążają one za cyklicznymi wzorami. Następnie musisz określić, czym są te cykle i jak się do siebie odnoszą.

Easy.

Łatwe.

You realize that there is a day and a night. Day always fallows night and night always fallows day. So you can use a border moment between night and day, sunset or sunrise as delimiting point which determines the beginning or the end of a day and night period. Then you can count days by counting the number of sunrises or sunsets. You have your time unit that you can use for measuring and expressing time. So you find a level place from where you can observe the sunrise and sunset all year round and start observing and counting. You want to mark the place from which you are observing the sky, so you use a stick, a post and stick it into the ground. So every morning you go to the post and observe the sun rising and every evening you go to the post and observe sun setting.

Zdajesz sobie sprawę, że jest dzień i noc. Dzień zawsze poprzedza noc, a noc zawsze poprzedza dzień. Możesz więc użyć momentu granicznego między nocą a dniem, zachodu lub wschodu słońca jako punktu wyznaczającego początek lub koniec okresu dnia i nocy. Następnie możesz liczyć dni, licząc liczbę wschodów lub zachodów słońca. Masz swoją jednostkę czasu, której możesz użyć do mierzenia i wyrażania czasu. Znajdź więc poziome miejsce na wzniesieniu, z którego możesz obserwować wschód i zachód słońca przez cały rok i zacznij obserwować i liczyć. Chcesz zaznaczyć miejsce, z którego obserwujesz niebo, więc używasz patyka, słupka i wbijasz go w ziemię. Więc każdego ranka idziesz na posterunek i obserwujesz wschodzące słońce, a każdego wieczoru idziesz na posterunek i obserwujesz zachód słońca.

You also realize that there is this body in the sky, moon and that as night after night passes, moon changes from a thin crescent to the full circle and back again.

Zdajesz sobie również sprawę, że na niebie jest takie ciało jak księżyc, i że w miarę upływu kolejnych nocy księżyc zmienia się z cienkiego półksiężyca w pełne koło i z powrotem.

Then one night during the full moon you start wandering after how many nights the moon will become full again. You take a stick (štap in Serbian) and you cut a notch into it for every night between the two full moons. Now you have a full moon cycle cut „into stick”, or cut „u štap” in Serbian. The archaic word for full moon in Serbian is still „uštap”, meaning „into stick”. You then repeat your marking of nights into another stick „štap” for the next moon cycle and the next. You compare your moon sticks „uštaps” and you realize that the full moon always comes after the same number of notches.

Potem pewnej nocy podczas pełni księżyca zaczynasz śledzić za ile nocy księżyc znów się stanie pełny. Bierzesz patyk (po serbsku uštap) i wycinasz w nim nacięcie na każdą noc między dwiema pełniami księżyca. Teraz masz cykl pełni księżyca wycięty „na patyku” lub wycięty „u štap” po serbsku. Archaicznym słowem oznaczającym pełnię księżyca w języku serbskim jest nadal „uštap”, co oznacza „w kij”. Następnie powtarzasz swoje oznaczanie nocy w innym kiju „ustap” dla następnego cyklu księżyca i następnego. Porównujesz swoje kije księżycowe „uštapy” i zdajesz sobie sprawę, że pełnia zawsze przychodzi po tej samej liczbie nacięć.

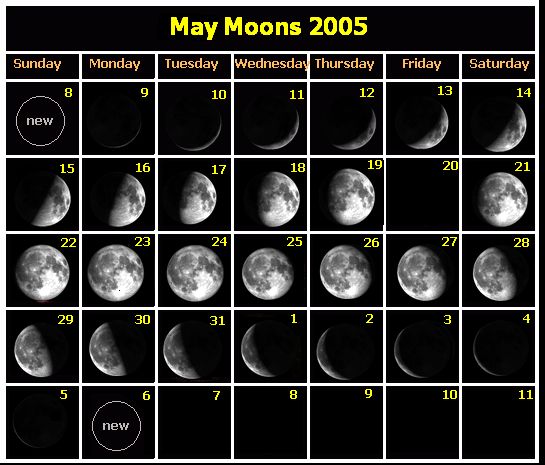

The Moon has phases because it orbits Earth, which causes the portion we see illuminated to change. The Moon takes 27.3 days to orbit Earth, but the lunar phase cycle (from new moon to new moon or from full moon to full moon) is 29.5 days. The Moon spends the extra 2.2 days „catching up” because Earth travels about 45 million miles around the Sun during the time the Moon completes one orbit around Earth.

Księżyc ma fazy, ponieważ krąży wokół Ziemi, co powoduje zmianę części, którą widzimy oświetloną. Księżyc okrąża Ziemię w 27,3 dnia, ale cykl faz księżyca (od nowiu do nowiu lub od pełni do pełni) trwa 29,5 dnia. Księżyc spędza dodatkowe 2,2 dnia na „doganianiu”, ponieważ Ziemia podróżuje około 45 milionów mil wokół Słońca w czasie, gdy Księżyc kończy jedną obrót wokół Ziemi.

You count notches on your moon stick, your „uštap”. You realize that the there are about 29 to 30 nights in a moon cycle. You start calling this period moon (mesec in Serbian). And you have a lunar calendar.

Liczysz nacięcia na swojej księżycowej lasce, swoim „uštap”. Zdajesz sobie sprawę, że w cyklu księżycowym jest około 29 do 30 nocy. Zaczynasz nazywać ten okres księżycem (mesec po serbsku). I masz kalendarz księżycowy.

Because the first day counting was associated with moon cycle calculation, the start of the day was counted from the sunset. This tradition was preserved in both Ireland and Serbia until very recently.

Ponieważ liczenie pierwszego dnia było związane z obliczaniem cyklu księżyca, początek dnia liczono od zachodu słońca. Ta tradycja została zachowana do niedawna zarówno w Irlandii, jak iw Serbii.

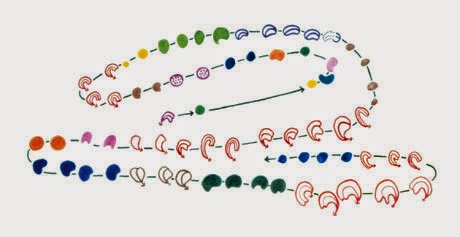

Because the tracking the change of the moon is easy, the first calendars were moon based. You could say to people: „we will meet at the next full moon” or „we will meet three full moons from today” or „we need to meet on the third day after the third full moon”. All people needed to do to keep their appointment was to use stick „štap” and mark the passing of full moons into the stick „uštap”.

Ponieważ śledzenie zmiany księżyca jest łatwe, pierwsze kalendarze opierały się na księżycu. Można powiedzieć ludziom: „spotkamy się przy następnej pełni księżyca” lub „od dziś spotkamy się po trzech pełniach księżyca” lub „musimy się spotkać trzeciego dnia po trzeciej pełni księżyca”. Wszystko, co ludzie musieli zrobić, aby dotrzymać terminu, to użyć sztyftu „ustap” i zaznaczyć na sztyfcie upływ pełni księżyca.

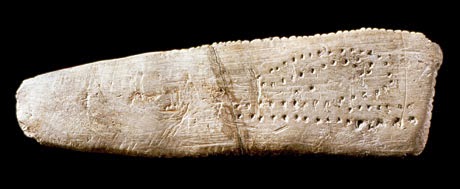

Alexander Marshack, in a controversial reading, believed that marks on a bone baton (c. 25,000 BC) represented a lunar calendar. Other marked bones may also represent lunar calendars. This is the Blanchard bone.

Alexander Marshack w kontrowersyjnym odczytaniu uważał, że ślady na kościanej pałce (ok. 25 000 pne) reprezentują kalendarz księżycowy. Inne zaznaczone kości mogą również reprezentować lunarne kalendarze. To jest kość Blancharda.

Podobnie Michael Rappenglueck uważa, że znaki na malowidle jaskiniowym sprzed 15 000 lat przedstawiają kalendarz księżycowy. Poniższe zdjęcie pochodzi z jaskini Lascaux we Francji. Kropki na obrazku mają przedstawiać dni w 29-dniowym cyklu księżyca.

This is a very good article arguing that the cave paintings in Lascaux represent a complex lunisolar calendar. I have my doubts mostly because the described system is too complicated. There is a much easier way to use sun and moon to calculate time.

To bardzo dobry artykuł dowodzący, że malowidła naskalne w Lascaux przedstawiają złożony kalendarz księżycowo-słoneczny. Wątpliwości mam przede wszystkim dlatego, że opisywany system jest zbyt skomplikowany. Istnieje znacznie łatwiejszy sposób wykorzystania słońca i księżyca do obliczenia czasu.

This is the 8000 years old lunar calendar found in Serbia. It is made from the tusk of a wild boar and is marked with engravings thought to denote a lunar cycle of 28 days, as well as the four phases of the moon. There is an empty space just before the last notch. Is this the 29th day, when the new moon vanishes from the sky and is not visible? The calendar fits into a pouch or a small bag so it can be said that this is probably the world’s first pocket calculator, calendar.

To jest liczący 8000 lat kalendarz księżycowy znaleziony w Serbii. Wykonany jest z kłów dzika i jest oznaczony rycinami, które mają oznaczać cykl księżycowy trwający 28 dni, a także cztery fazy księżyca. Tuż przed ostatnim nacięciem jest pusta przestrzeń. Czy to 29 dzień, kiedy księżyc w nowiu znika z nieba i nie jest widoczny? Kalendarz mieści się w saszetce lub małej torebce, więc można powiedzieć, że jest to prawdopodobnie pierwszy na świecie kalkulator kieszonkowy, kalendarz.

The problem is that this system is good enough for short term planning which is not related to the vegetative cycle. But if you try to use moon calendar to plan your activities related to vegetative cycle you will realize that the moon calendar is not the right tool for the job, because the Earth vegetative cycle is governed not by the moon but by the Sun. If a specific solar governed event, like the beginning of spring fell on the 3rd full moon this year, it will not fall on the 3rd full moon next year. Because the lunar year, the sum of full moons in one year, is shorter than the solar year, the new lunar year will start earlier than the solar year and the solar event will occur later than previous year. And this lagging of the solar events will be bigger and bigger as years pass.

Problem polega na tym, że ten system jest wystarczająco dobry do planowania krótkoterminowego, które nie jest związane z cyklem wegetatywnym. Ale jeśli spróbujesz wykorzystać kalendarz księżycowy do planowania swoich działań związanych z cyklem wegetacyjnym, zdasz sobie sprawę, że kalendarz księżycowy nie jest odpowiednim narzędziem do pracy, ponieważ ziemskim cyklem wegetacyjnym rządzi nie księżyc, ale Słońce. Jeśli określone wydarzenie zarządzane przez energię słoneczną, takie jak początek wiosny, przypadło na trzecią pełnię księżyca w tym roku, nie wypadnie na trzecią pełnię księżyca w przyszłym roku. Ponieważ rok księżycowy, suma pełnych księżyców w jednym roku, jest krótszy niż rok słoneczny, nowy rok księżycowy rozpocznie się wcześniej niż rok słoneczny, a wydarzenie słoneczne nastąpi później niż rok poprzedni. A to opóźnienie wydarzeń słonecznych będzie coraz większe w miarę upływu lat.

So how do you solve this problem?

Jak więc rozwiązać ten problem?

You realize that you need to start using the sun cycle in order to determine the exact timing of vegetative events during the solar year. You start with what you know about the sun. You know that the sun is changing in a longer cycle. It gets higher over the horizon and hotter and then lower and colder over many moons. The trick is to determine exactly when the solar cycle starts and how many moons does it last.

Zdajesz sobie sprawę, że musisz zacząć korzystać z cyklu słonecznego, aby określić dokładny czas wydarzeń wegetatywnych w ciągu roku słonecznego. Zaczynasz od tego, co wiesz o słońcu. Wiesz, że słońce zmienia się w dłuższym cyklu. Wznosi się nad horyzontem i staje się gorętszy, a następnie niższy i zimniejszy przez wiele księżyców. Sztuczka polega na dokładnym określeniu, kiedy zaczyna się cykl słoneczny i ile księżyców trwa.

Remember the level place from where you were observing the sunrise and sunset all year round in order to determine the number of days in a moon? The observatory? You are standing next to the observation pole and observing sunrises and sunsets. As you are observing the sunrises and sunsets, you notice that the point where sun rises is not the same as the point where sun sets. The sun rises on the left side of the horizon, travels across the sky from left to right and sets at the opposite right side of the horizon. As days pass you realize that the point where the sun rises moves along the horizon. So does the point where the sun sets. You notice that the sunrise point moves during the spring further and further to the left and the sunset point further and further to the right. So the sun needs to travel longer across the sky and the day is longer and longer and hotter and hotter. Then at some point during the summer the sunrise and sunset points start moving in the opposite direction. The sunrise point starts moving to the right and sunset point starts moving to the left. They get closer and closer to each other, so the sun has to travel shorter distance between the sunrise and sunset and the day is shorter and shorter and colder and colder.

Pamiętasz poziome miejsce, z którego przez cały rok obserwowałeś wschód i zachód słońca, aby określić liczbę dni na księżycu? Obserwatorium? Stoisz obok słupa obserwacyjnego i obserwujesz wschody i zachody słońca. Obserwując wschody i zachody słońca, zauważasz, że punkt, w którym słońce wschodzi, nie jest tym samym, co punkt, w którym zachodzi. Słońce wschodzi po lewej stronie horyzontu, wędruje po niebie od lewej do prawej i zachodzi po przeciwnej, prawej stronie horyzontu. W miarę upływu dni zdajesz sobie sprawę, że punkt, w którym wschodzi słońce, przesuwa się wzdłuż horyzontu. Podobnie punkt, w którym zachodzi słońce. Zauważasz, że punkt wschodu słońca przesuwa się wiosną coraz bardziej w lewo, a punkt zachodu słońca coraz bardziej w prawo. Więc słońce musi dłużej podróżować po niebie, a dzień jest coraz dłuższy i coraz gorętszy. W pewnym momencie latem punkty wschodu i zachodu słońca zaczynają przesuwać się w przeciwnym kierunku. Punkt wschodu zaczyna przesuwać się w prawo, a punkt zachodu słońca w lewo. Zbliżają się do siebie coraz bardziej, przez co słońce musi przebyć coraz krótszą drogę między wschodem a zachodem słońca, a dzień jest coraz krótszy i coraz zimniejszy.

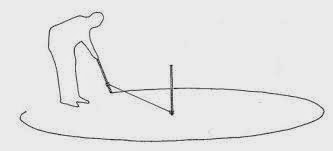

This is extremely important observation if you depend on solar vegetative cycle for your survival. If the length and heat of the day depends on the position of the sunrise and sunset points, then determining how they move becomes imperative. You know that the days when the sunrise and sunset points change the direction of their movements, fall in the middle of the coldest and hottest part of the year. You are of course more interested in the turning point which falls in the middle of the cold dark part of the year. You want to know if, and this was for our ancestors very real IF, and when the sunrise and sunset points will start moving further and further away from each other, because that will mean that the days will start getting longer and hotter again. So you start observing the the horizon and you try to remember where the sun rose and set yesterday in order to compare it with the sunrise and sunset position today. But that is difficult and imprecise. It would be much better if you could mark the points of sunrise and sunset every day in some way and then observe the relative position of the sunrise and sunset points to the marks. So you decide to use two stakes, poles as markers. But it is difficult to mark the exact point of sunrise and sunset if the horizon is uneven. It would be much easier if the horizon is horizontal, smooth and elevated all around you so that the observation and marking of the sunrise and sunset points becomes more precise. So you decide to create an artificial horizontal smooth horizon which will mask the real horizon. You take a long enough rope, tie it to the observation pole and then walk around the observation pole. As you walk you mark a circle with the center in the observation pole.

Jest to niezwykle ważna obserwacja, jeśli polegasz na słonecznym cyklu wegetatywnym dla swojego przetrwania. Jeśli długość i upał dnia zależą od położenia punktów wschodu i zachodu słońca, określenie, w jaki sposób się poruszają, staje się koniecznością. Wiesz, że dni, w których punkty wschodu i zachodu słońca zmieniają kierunek swojego ruchu, przypadają na środek najzimniejszej i najgorętszej części roku. Oczywiście bardziej interesuje Cię punkt zwrotny, który przypada na środek zimnej, ciemnej pory roku. Chcesz wiedzieć, czy, a dla naszych przodków było to bardzo realne JEŚLI, i kiedy punkty wschodu i zachodu słońca zaczną się coraz bardziej oddalać od siebie, bo to będzie oznaczać, że dni znowu zaczną się wydłużać i gorętsze. Więc zaczynasz obserwować służąc horyzontowi i próbujesz sobie przypomnieć, gdzie wczoraj wschodziło i zachodziło słońce, aby porównać to z dzisiejszą pozycją wschodu i zachodu słońca. Ale to trudne i nieprecyzyjne. Byłoby znacznie lepiej, gdybyś codziennie w jakiś sposób zaznaczał punkty wschodu i zachodu słońca, a następnie obserwował względne położenie punktów wschodu i zachodu słońca względem tych znaków. Decydujesz się więc użyć dwóch tyczek jako znaczników. Ale trudno jest wyznaczyć dokładny punkt wschodu i zachodu słońca, jeśli horyzont jest nierówny. Byłoby znacznie łatwiej, gdyby horyzont był poziomy, gładki i wzniesiony wokół ciebie, dzięki czemu obserwacja i oznaczanie punktów wschodu i zachodu słońca stanie się bardziej precyzyjne. Postanawiasz więc stworzyć sztuczny poziomy gładki horyzont, który zamaskuje prawdziwy horyzont. Bierzesz odpowiednio długą linę, przywiązujesz ją do słupa obserwacyjnego, a następnie obchodzisz słup obserwacyjny. Idąc, zaznaczasz okrąg ze środkiem na tyczce obserwacyjnej.

You then dig a circular trench along the circle and pile up the the dug out earth on the edge of the circle to form the bank. You build a henge like this original earthen henge in Stonehenge. You can read my article about henges here.

Następnie wykopujesz okrągły rów wzdłuż okręgu i układasz wykopaną ziemię na krawędzi okręgu, aby utworzyć brzeg. Budujesz henge jak ten oryginalny ziemny krąg w Stonehenge. Możesz przeczytać mój artykuł o kręgach tutaj.

Now when the sun rises or sets it will be easy to mark the exact spot of sunrise and sunset with a stake stuck into the elevated earthen bank. Every morning and evening you observe the new position of the sunrise and sunset points. If the sun does not rise and set at the points marked with the yesterday’s stakes, you stick new stakes into the earthen bank to mark the new position of the sunrise and sunset points, and you remove the yesterday’s stakes. As the days get colder and colder, the sunrise and sunset stakes will get closer and closer to each other. Then one day in the middle of the winter, the movement of the sunrise and sunset points will stop. The sun will rise at the same position behind the yesterday’s sunrise stake and will set at the same position behind the yesterday’s sunset stake. That day is the winter turning point, the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. You mark these two points with the permanent taller stakes. So when the sun again rises and sets behind these two sunrise and sunset stakes you will know that the winter turning point, the winter solstice, the shortest day has arrived again. You can now build a high wall, a fence, a palisade made of wooden stakes, around the central observation stake, within the earthen henge, in order to create artificial smooth horizontal elevated horizon to completely mask the real horizon. You then make two gates, both in the earthen bank and in the wooden palisade within it, at the exact places where the winter solstice turning point stakes were. So in the future, on the day of the winter turning point, the winter solstice, the people standing in the center of the sun circle will see the sun rise and set through the „sun gates”.

Teraz, gdy słońce wschodzi lub zachodzi, łatwo będzie zaznaczyć dokładne miejsce wschodu i zachodu słońca za pomocą kołka wbitego w uniesiony ziemny brzeg. Codziennie rano i wieczorem obserwujesz nowe położenie punktów wschodu i zachodu słońca. Jeśli słońce nie wschodzi i nie zachodzi w punktach zaznaczonych wczorajszymi palikami, wbijasz nowe paliki w ziemny brzeg, aby zaznaczyć nowe położenie punktów wschodu i zachodu słońca, i usuwasz wczorajsze paliki. W miarę jak dni stają się coraz zimniejsze, wschody i zachody słońca będą się do siebie zbliżać. Pewnego dnia w środku zimy ruch punktów wschodu i zachodu słońca ustanie. Słońce wzejdzie w tym samym miejscu za słupkiem wczorajszego wschodu słońca i zajdzie w tym samym miejscu za słupkiem wczorajszego zachodu słońca. Ten dzień jest punktem zwrotnym zimy, przesileniem zimowym, najkrótszym dniem w roku. Zaznaczasz te dwa punkty stałymi wyższymi stawkami. Więc kiedy słońce ponownie wzejdzie i zajdzie za tymi dwoma słupkami wschodu i zachodu słońca, będziesz wiedział, że punkt zwrotny zimy, przesilenie zimowe, najkrótszy dzień ponownie nadszedł. Możesz teraz zbudować wysoki mur, ogrodzenie, palisadę z drewnianych palików wokół centralnego słupka obserwacyjnego, w obrębie ziemnego kręgu, aby stworzyć sztucznie gładki poziomy podwyższony horyzont, aby całkowicie zamaskować prawdziwy horyzont. Następnie tworzysz dwie bramy, zarówno w ziemnym brzegu, jak iw drewnianej palisadzie w jego obrębie, dokładnie w miejscach, w których znajdowały się paliki punktu zwrotnego przesilenia zimowego. Tak więc w przyszłości, w dniu zimowego punktu zwrotnego, przesilenia zimowego, ludzie stojący w środku koła słonecznego zobaczą wschody i zachody słońca przez „słoneczne wrota”.

This is exactly what people did in Goseck circle one of the oldest henge solar observatories in the world.

Dokładnie to zrobili ludzie w kręgu Goseck [CB – Gąsiecku], jednym z najstarszych obserwatoriów słonecznych kręgów na świecie.

At the winter solstice, observers at the center would have seen the sun rise and set through the southeast and southwest gates.

Podczas przesilenia zimowego obserwatorzy w centrum widzieliby wschody i zachody słońca przez południowo-wschodnią i południowo-zachodnią bramę.

You can do exactly the same with the boundary turning points in the middle of the summer. You can make gates at these two points or just at the summer solstice sunrise point and watch the sun rise through the sun gate every summer solstice like in so many henges in England.

Dokładnie to samo można zrobić z granicznymi punktami zwrotnymi w środku lata. Możesz zrobić bramy w tych dwóch punktach lub po prostu w punkcie wschodu słońca przesilenia letniego i obserwować wschody słońca przez bramę słońca każdego przesilenia letniego, jak w wielu hengach w Anglii.

Now you have a ceremonial sun circle, which can be used year after year to determine the the beginning of the solar year but also for worshiping of the high god, the Sun.

Teraz masz ceremonialny krąg słoneczny, który może być używany rok po roku do określania początku roku słonecznego, ale także do oddawania czci najwyższemu bogu, Słońcu.

Then from the starting point of the winter solstice, you count number of days and number of full moons until the next starting point. You get a long stick and you cut a notch for every day and a cross for a full moon day. You are basically determining the number of days in a solar year and the number of „moons” in a solar year and you record them „u štap” in a stick. Next time the winter solstice arrives, you will know exactly how many full moons there are in a solar year and how many „extra” days are you need to reach the end of the solar year. Then when the sun rises through the sun gate, and the new solar year begins, a celebration is held to celebrate the rebirth of the sun and the new year calendar stick is cut.

Następnie od punktu początkowego przesilenia zimowego liczysz liczbę dni i liczbę pełni księżyca do następnego punktu początkowego. Dostajesz długi kij i wycinasz nacięcie na każdy dzień i krzyżyk na dzień pełni księżyca. Zasadniczo określasz liczbę dni w roku słonecznym i liczbę „księżyców” w roku słonecznym i zapisujesz je „u štap” w patyku. Następnym razem, gdy nadejdzie przesilenie zimowe, będziesz dokładnie wiedział, ile jest pełnych księżyców w roku słonecznym i ile „dodatkowych” dni potrzebujesz, aby osiągnąć koniec roku słonecznego. Następnie, kiedy słońce wschodzi przez słoneczną bramę i zaczyna się nowy rok słoneczny, odbywa się uroczystość, aby uczcić odrodzenie słońca i odcina się kij kalendarza nowego roku.

How was this year calendar stick cut?

Jak wycięto tegoroczny kij kalendarzowy?

The year stick was cut in such a way that it first counted the days of full moons from the day of the winter solstice, regardless whether there was actually a full moon or not. A notch was made for every day and every time the number of days in a full was reached, the full moon mark was made in the calendar stick. At the end of the last full moon period, people were left with the extra days, the days which they needed to add to reach the number of days in the solar year. These days were added to the end of the calendar stick. These extra days were called „dead days”. They were outside the calendar, outside the time, between the sun circle and the moon circle. These were the days when no work was done, the taboo days, when everyone was at the sun circle, waiting for the sun to be „reborn” and for another solar year to start. People originally probably used the 29 days full moons. This calendar had 12 full moons and 17 extra dead days. At some point one day was added to each full moon and moons ended up having 30 days each. This calendar had 12 full moons and 5 extra dead days.

Patyk roczny został przecięty w taki sposób, że najpierw liczył dni pełni księżyca od dnia przesilenia zimowego, niezależnie od tego, czy faktycznie była pełnia, czy nie. Na każdy dzień robiono nacięcie i za każdym razem, gdy osiągnięto liczbę dni w pełni, na drążku kalendarza robiono znak pełni księżyca. Pod koniec ostatniej pełni księżyca ludziom pozostawały dodatkowe dni, dni, które musieli dodać, aby osiągnąć liczbę dni w roku słonecznym. Dni te zostały dodane na końcu drążka kalendarza. Te dodatkowe dni nazywano „dniami martwymi”. Byli poza kalendarzem, poza czasem, między kręgiem słońca a kręgiem księżyca. To były dni, kiedy nie wykonywano żadnej pracy, dni tabu, kiedy wszyscy byli w kręgu słonecznym, czekając, aż słońce „odrodzi się” i rozpocznie się kolejny rok słoneczny. Pierwotnie ludzie prawdopodobnie używali 29 dni pełni księżyca. Ten kalendarz miał 12 pełnych księżyców i 17 dodatkowych martwych dni. W pewnym momencie do każdej pełni księżyca dodawano jeden dzień, a księżyce kończyły się na 30 dniach. Ten kalendarz miał 12 pełnych księżyców i 5 dodatkowych martwych dni.

In Serbian tradition the name of these 5 extra „dead days” is preserved as (Mratinci, Mrt + den, literally dead day) which in Serbian Orthodox church calendar fall between the 9. do 14. of November. These dead days are also called „vučji dani” or wolf days.

W tradycji serbskiej nazwa tych 5 dodatkowych „dni martwych” jest zachowana jako (Mratinci, Mrt + den, dosłownie dzień martwy), które w kalendarzu serbskiej cerkwi przypadają między 9. a 14. listopada. Te martwe dni nazywane są również „vučji dani” lub dniami wilka.

The calendar stick with all the days of the solar year divided into the days of the full moons and the dead days, allowed everyone to count time in the same way, and to coordinate their actions without the need to observe the sky and know anything about the movements of the sun and moon. Now vegetative events of the solar year were fixed in the lunar calendar. Also this system made sure that every year was a true solar year, starting at the exactly the right time and lasting exactly the same number of lunar calendar days. It was the dead days at the end of the solar year that allowed year length adjustment.

Kalendarz ze wszystkimi dniami roku słonecznego z podziałem na dni pełni i dni martwe, pozwalał każdemu tak samo liczyć czas i koordynować swoje działania bez konieczności obserwacji nieba i wiedzy o nim ruchy słońca i księżyca. Teraz wegetatywne wydarzenia roku słonecznego zostały ustalone w kalendarzu księżycowym. Również ten system gwarantował, że każdy rok był prawdziwym rokiem słonecznym, rozpoczynającym się dokładnie we właściwym czasie i trwającym dokładnie taką samą liczbę księżycowych dni kalendarzowych. Dopiero martwe dni pod koniec roku słonecznego pozwalały na dostosowanie długości roku.

So after the celebration at the sun circle is finished, everyone goes away to their villages, bringing with them their year stick calendars. Every day, they cut away a piece of the year stick up to the first notch, marking the passing of the previous day. Then one day, when the last full moon mark is reached on the stick, at the beginning of the dead days, everyone comes back to the sun circle to witness the rebirth of the sun, and to get the new calendar stick carved for them. I love the way these calendars are not made to record the past, but to fix the present moment in time and to allow planning for the future.

Tak więc po zakończeniu uroczystości w kręgu słonecznym wszyscy udają się do swoich wiosek, zabierając ze sobą kalendarze roczne. Każdego dnia odcinają kawałek roku do pierwszego nacięcia, oznaczając koniec poprzedniego dnia. Pewnego dnia, kiedy ostatni znak pełni księżyca zostanie osiągnięty na patyku, na początku martwych dni, wszyscy wracają do kręgu słonecznego, aby być świadkami odrodzenia słońca i wyrzeźbić dla nich nowy kalendarz. Uwielbiam sposób, w jaki te kalendarze nie są tworzone, aby zapisywać przeszłość, ale aby utrwalić teraźniejszość w czasie i umożliwić planowanie na przyszłość.

It seems that at some stage the order of „dead days” and full moons was reversed and the dead days were counted as the first days after the winter solstice.

Wydaje się, że w pewnym momencie kolejność „martwych dni” i pełni księżyca została odwrócona i martwe dni były liczone jako pierwsze dni po przesileniu zimowym.

In Serbian tradition, Sun, the „Višnji Bog”, the High God, is perceived as a living being, which is born every year in the winter. He then grows into a young man Jarilo on the 6th of May the day of the strongest vegetative, reproductive power of the sun. Then he becomes the powerful ruler Vid at the summer solstice, 21st of June the longest day of the year. He then becomes the terrible warrior Perun on the 2nd of August the hottest day of the year. Then the Sun God dies on the day of the winter solstice, the 21st of December the shortest day of the year. The Sun God then goes into the underworld, where it spends 5 days and emerges, reborn on the 25th of December. These 5 days that the sun spends in the underworld, are the extra days, the dead days, the days which are outside of the calendar.

W tradycji serbskiej Słońce, „Višnji Bog”, Najwyższy Bóg, jest postrzegane jako żywa istota, która rodzi się co roku zimą. Następnie wyrasta na młodzieńca Jaryło 6 maja, w dniu najsilniejszej wegetatywnej, reprodukcyjnej mocy słońca. Następnie staje się potężnym władcą Videm w czasie letniego przesilenia, 21 czerwca, najdłuższego dnia w roku. Następnie staje się strasznym wojownikiem Perunem 2 sierpnia, najgorętszego dnia w roku. Następnie Bóg Słońca umiera w dniu przesilenia zimowego, 21 grudnia, najkrótszego dnia w roku. Następnie Bóg Słońca udaje się do podziemnego świata, gdzie spędza 5 dni i wyłania się, odradzając się 25 grudnia. Te 5 dni, które słońce spędza w zaświatach, to dodatkowe dni, martwe dni, dni, które są poza kalendarzem.

This is why Christ the Son God, was born on the 25th of December, the same day when Mithra the Sun God was born before him.

Dlatego Chrystus Syn Boży narodził się 25 grudnia, tego samego dnia, w którym przed nim narodził się Bóg Słońca Mitra.

Epiphany which traditionally falls on January 6, is a Christian feast day that celebrates the revelation of God the Son as a human being in Jesus Christ. The earliest reference to Epiphany as a Christian feast was in A.D. 361, by Ammianus Marcellinus St. Epiphanius says that January 6 is hemera genethlion toutestin epiphanion (Christ’s „Birthday; that is, His Epiphany”). Alternative names for the feast in Greek include η Ημέρα των Φώτων, i Imera ton Foton (modern Greek pronunciation), hē hēmera tōn phōtōn (restored classic pronunciation), „The Day of the Lights”, and τα Φώτα, ta Fota, „The Lights”.

Objawienie Pańskie, które tradycyjnie przypada 6 stycznia, jest chrześcijańskim świętem upamiętniającym objawienie się Boga Syna jako istoty ludzkiej w Jezusie Chrystusie. Najwcześniejsza wzmianka o Objawieniu Pańskim jako chrześcijańskim święcie pochodzi z 361 r. n.e. od Ammianusa Marcellinusa. Św. Epifaniusz mówi, że 6 stycznia to hemera genethlion toutestin epiphanion („Urodziny Chrystusa, czyli Jego Objawienie Pańskie”). Alternatywne nazwy święta w języku greckim to η Ημέρα των Φώτων, i Imera ton Foton (współczesna wymowa grecka), hē hēmera tōn phōtōn (przywrócona klasyczna wymowa), „Dzień świateł” i τα Φώτα, ta Fota, „Światła”.

Was the night between the 6th and the 7th of January, the old end of the 17 dead days, when the month had 29 days? The day when the sun reappeared from the underworld and revealed itself to the people as the beginning of a first day of the first moon of the new year? Is this why this day is still a holy day of the revelation, birthday of the Son the God who replaced Sun God? Is this why this day is called the Day of the Lights?

Czy noc z 6 na 7 stycznia była końcem 17 martwych dni, kiedy miesiąc miał 29 dni? Dzień, w którym słońce wyłoniło się z zaświatów i ukazało się ludziom jako początek pierwszego dnia pierwszego księżyca nowego roku? Czy dlatego ten dzień jest nadal świętem objawienia, narodzin Syna Boga, który zastąpił Boga Słońca? Czy to dlatego ten dzień nazywa się Dniem Świateł?

But in Serbian tradition we also find the 5 dead days at the end of the solar year. When the beginning of the year was moved to the spring Equinox in March, the dead days became the Baba’s days, the days of the Baba Mara, Mora, Morana, Marzana, the goddess of winter and death. They are the last 5 days of winter, the dead days after the end of the last 30 days full moon and just before the beginning of the spring. In Serbia these days are often in legends called jarići meaning billy goats. Now vanished stone circle from the south of Serbia was recorded as being called Baba i jarići. Baba was the central stone pillar and jarići were the circle stones. Were there five of them? Is this why so many stone circles from Ireland have exactly 5 stones? Maybe these were days during which Jarilo, the young sun, the god of spring is going through the underworld before being born to start new vegetative cycle. There is an expression in Serbia, which probably dates to the time of the forced Christianization of the Serbs in 13th Century: „Ja ga krstim a on jariće broji” meaning „I am baptizing him and he is still counting billy goats”. The expression means wasting time on someone and shows how strong the old faith was among the Serbs. Are the billy goats from this expression the same 5 dead days of the old calendar? Are all these beliefs and customs echos from the days when first henges were built 7000 years ago in order to create the first lunisolar calendar?

Ale w serbskiej tradycji znajdujemy również 5 martwych dni na koniec roku słonecznego. Gdy początek roku przesunięto na marcową równonoc wiosenną, martwe dni stały się dniami Baby, dniami Baby Mara, Mory, Morany, Marzany, bogini zimy i śmierci. To ostatnie 5 dni zimy, martwe dni po zakończeniu ostatnich 30 dni pełni księżyca i tuż przed początkiem wiosny. W Serbii te dni są często w legendach nazywane jarići, co oznacza koziołki. Obecnie zaginiony kamienny krąg z południa Serbii został nagrany jako Baba i jarići. Baba był centralnym kamiennym filarem, a jarići były kamieniami kręgu. Czy było ich pięciu? Czy to dlatego tak wiele kamiennych kręgów z Irlandii ma dokładnie 5 kamieni? Może to były dni, podczas których Jaryło, młode słońce, bóg wiosny, przedtem przechodzi przez podziemia gdzie zostaje odrodzony urodzony, aby rozpocząć nowy cykl wegetatywny. W Serbii istnieje wyrażenie, które prawdopodobnie pochodzi z czasów przymusowej chrystianizacji Serbów w XIII wieku: „Ja ga krstim a on jariće broji”, co oznacza „chrzczę go, a on wciąż liczy koziołki”. Wyrażenie oznacza marnowanie czasu na kogoś i pokazuje, jak silna była stara wiara wśród Serbów. Czy koziołki z tego wyrażenia to te same 5 martwych dni ze starego kalendarza? Czy wszystkie te wierzenia i zwyczaje są echem z czasów, gdy 7000 lat temu zbudowano pierwsze kury w celu stworzenia pierwszego kalendarza księżycowo-słonecznego?

źródło: https://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2014/06/calendar.html