Christmas trees from garden of eden

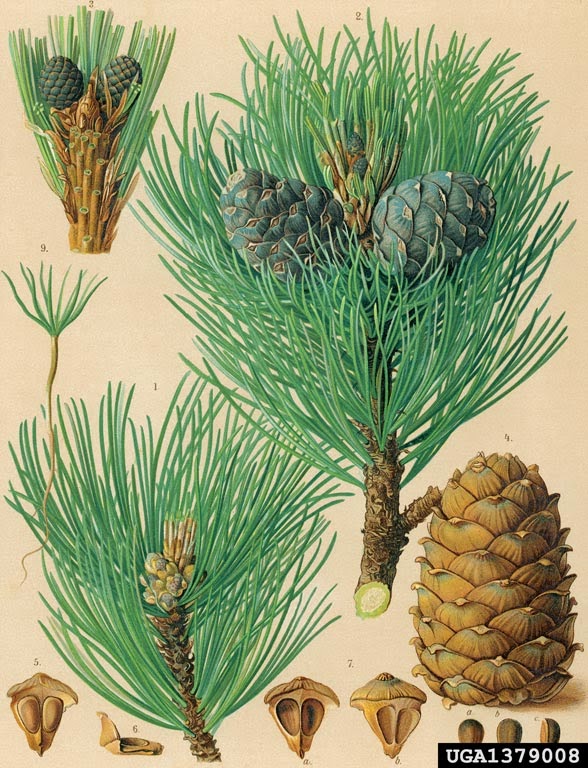

The stone pine (Pinus pinea), also called Italian stone pine, umbrella pine and parasol pine, is a tree from the pine family (Pinaceae). It has been used and cultivated for its edible pine nuts since prehistoric times. The tree is native to the Mediterranean region. At present it is found in Europe ( Iberia, Italy, Southern France, Balkans, Aegean and Western Turkey), Western Asia (Southern Anatolia, Lebanon, Syria, Northern Israel) and North Africa (Morocco and Algeria). It grows in dry arid areas mixed with oaks and shrubs.

Sosna zwyczajna (Pinus pinea), zwana także sosną włoską, sosną parasolową i sosną parasolową, jest drzewem z rodziny sosnowatych (Pinaceae). Od czasów prehistorycznych był używany i uprawiany ze względu na jadalne orzeszki piniowe. Drzewo pochodzi z regionu śródziemnomorskiego. Obecnie występuje w Europie (Iberia, Włochy, południowa Francja, Bałkany, Morze Egejskie i zachodnia Turcja), Azji Zachodniej (południowa Anatolia, Liban, Syria, północny Izrael) i Afryce Północnej (Maroko i Algieria). Rośnie na suchych i suchych obszarach zmieszanych z dębami i krzewami.

But I believe that the root of this word is much simpler. In Serbian we have word „jede” which is in the old south Serbian dialect found in a form „ede”. This word means eat. It comes from the Proto Indo European root „*h₁ed” meaning to eat from which the English word eat also comes from. In Serbian we have the following words derived from the root „ede, jede”:

Ale wierzę, że rdzeń tego słowa jest znacznie prostszy. W języku serbskim mamy słowo „jede”, które w starym południowo-serbskim dialekcie występuje w formie „ede”. To słowo oznacza jeść. Pochodzi od protoindoeuropejskiego rdzenia „*h₁ed” oznaczającego jeść, z którego pochodzi również angielskie słowo jeść. W języku serbskim mamy następujące słowa pochodzące od rdzenia „ede, jede”:

jelo, jedja, jedivo, jestivo – food

edenje, jedenje – food (south Serbian dialect). Literally means eating and is the direct cognate of the English word eating.

eden, jeden – eaten

jelo, jedja, jedivo, jestivo – jedzenie

edenje, jedenje – jedzenie (dialekt południowo-serbski). Dosłownie oznacza jedzenie i jest bezpośrednim pokrewnym angielskiemu słowu eaten – jedzenie. eden, jeden – zjedzony

The garden of Eden was the garden of edible trees. It was the garden of god given food, of edenje, jedenje, eating. Is this the actual original, simple meaning of the word Eden = Eating, Food? Was the garden of Eden the post glacial Northern hemisphere, which was going through an incredible transformation from a cold wasteland into a lush garden full of easily obtainable abundant food? And was then, as William Bryant Logan says, this garden of Eden responsible for human transformation from humans into modern humans? I believe so. If we look at the Mesolithic northern hemisphere, we see first civilizations hatching in Western and Easten Asia, In the Balkans and Iberia, in north Africa and in Mexico, all situated in „gardens of edenje”, gardens of eating, food, full of easy to collect and store acorns, nuts, roots, wild grains, and easy to catch small game, fish, shellfish and snails. The garden of Eden was the old Golden Age of the Greeks and Romans, the post glacial northern hemisphere.

In the northern hemisphere, the shortest day and longest night of the year, the winter solstice, falls on the 21st of December. Many ancient people believed that the sun was a living god and that winter came every year because the sun god had become old, sick and weak. The sign of this was the fact that the days were getting shorter and colder, and that the vegetation was dying. Winter solstice was the turning point when the days start getting longer again heralding the arrival of spring, warmth and new vegetative cycle. People who depended on this vegetative cycle celebrated the solstice as the rebirth of the sun god.

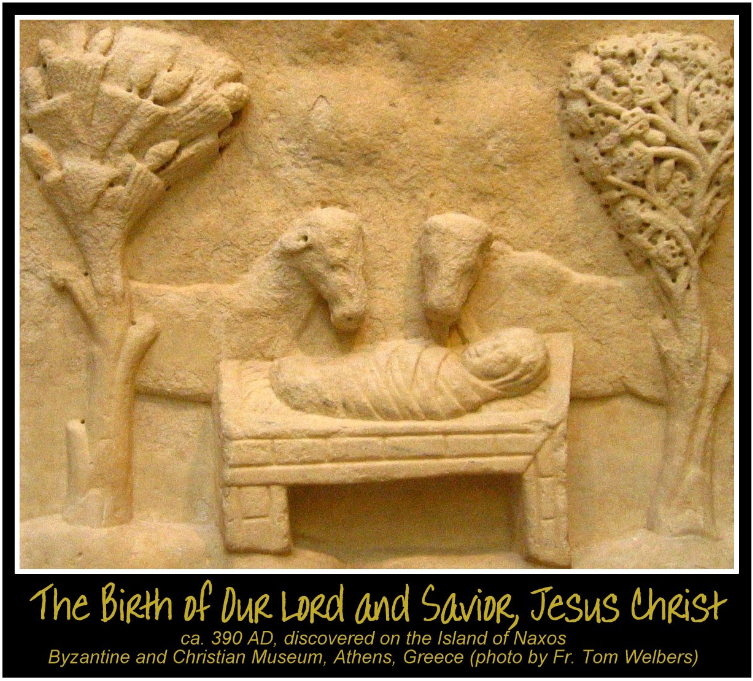

The accepted theory is that around the time of the Winter Solstice, people decorated their homes and temples with evergreen branches and worshipped evergreen trees and plants in general, because the evergreen plants reminded them of all the green plants that would grow again when the sun god gets reborn after the Winter Solstice. This is a good enough explanation. But it is the choice of these Winter Solstice (Christmas) trees which is very interesting: Oak and Pine (Spruce, Fir). I believe that the choice of the choice of these trees has as much to do with the fact that they were the oldest starch (bread) bearing trees, as with the fact that they were evergreen. To illustrate this I will here give the list of the European Winter Solstice (Christmas) traditions involving trees to show that all of these trees are Either Oak or Pine (Spruce, Fir), the oldest starch (bread) bearing trees, the trees that appear on the Naxos stelle.

Przyjętą teorią jest to, że w okresie przesilenia zimowego ludzie dekorowali swoje domy i świątynie wiecznie zielonymi gałęziami i ogólnie czcili wiecznie zielone drzewa i rośliny, ponieważ wiecznie zielone rośliny przypominały im wszystkie zielone rośliny, które odrosną ponownie, gdy bóg słońca odradza się po przesileniu zimowym. To wystarczająco dobre wyjaśnienie. Ale to wybór tych drzewek przesilenia zimowego (bożonarodzeniowego) jest bardzo interesujący: dąb i sosna (świerk, jodła). Uważam, że wybór tych drzew ma tyle wspólnego z faktem, że były to najstarsze drzewa dające skrobię (chleb), co z tym, że były wiecznie zielone. Aby to zilustrować, podam tutaj listę europejskich tradycji związanych z przesileniem zimowym (Boże Narodzenie) związanych z drzewami, aby pokazać, że wszystkie te drzewa to dąb lub sosna (świerk, jodła), najstarsze drzewa dające skrobię (chleb), drzewa, które pojawiają się na steli z Naxos.

Romans

Rzymianie

Romans marked the solstice with a feast called the Saturnalia in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture. In Roman mythology, Saturn was an agricultural deity who was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labor in a state of social egalitarianism. The revelries of Saturnalia were supposed to reflect the conditions of the lost mythical age, not all of them desirable. The Greek equivalent was the Kronia. The Romans knew that the solstice meant that soon farms and orchards would be green and fruitful. To mark the occasion, they decorated their homes and temples with evergreen boughs. We are told that it was holly tree branches that were used because they don’t lose their leaves during the winter. But is it possible that it wasn’t holly tree branches that were used, but the branches of the evergreen Mediterranean oaks, such as Quercus coccifera (Kermes Oak), Quercus suber (Cork Oak) and Quercus ilex (Holm Oak)? Holm oak is called Holm oak because its leaves resemble holly tree leaves, holm being the old name for holly. The thing is the other two evergreen oak trees have leaves which resemble holly leaves even more. Have a look at these pictures and tell me if it was easy to confuse the evergreen oaks and holly:

Rzymianie obchodzili przesilenie świętem zwanym Saturnaliami ku czci Saturna, boga rolnictwa. W mitologii rzymskiej Saturn był bóstwem rolniczym, o którym mówiono, że panował nad światem w Złotym Wieku, kiedy ludzie cieszyli się spontaniczną obfitością ziemi bez pracy w stanie społecznego egalitaryzmu. Hulanki Saturnaliów miały odzwierciedlać warunki utraconej epoki mitycznej, nie wszystkie z nich pożądane. Greckim odpowiednikiem była Kronia. Rzymianie wiedzieli, że przesilenie oznaczało, że wkrótce farmy i sady będą zielone i owocne. Aby uczcić tę okazję, dekorowali swoje domy i świątynie wiecznie zielonymi gałęziami. Mówi się nam, że używano gałęzi ostrokrzewu, ponieważ nie gubią liści na zimę. Ale czy to możliwe, że nie używano gałęzi ostrokrzewu, ale gałęzie wiecznie zielonych dębów śródziemnomorskich, takich jak Quercus coccifera (Dąb Kermes), Quercus suber (Dąb Korkowy) i Quercus ilex (Dąb Holm)? Dąb Holm nazywany jest dębem bezszypułkowym, ponieważ jego liście przypominają liście ostrokrzewu, przy czym holm to dawna nazwa ostrokrzewu. Rzecz w tym, że pozostałe dwa wiecznie zielone dęby mają liście, które jeszcze bardziej przypominają liście ostrokrzewu. Spójrzcie na te zdjęcia i powiedzcie, czy łatwo było pomylić wiecznie zielone dęby i ostrokrzewy:

Holly

Ostrokrzew

[W związku z tematem krzewu szodrogodowego – tutaj ostrokrzewu z późnych kultur Rzymian i Greków, trzeba stwierdzić że w Europie wystęują tylko 3 gatunki Ostrokrzewu, a z tego żaden po pólnocnej stronie Karpat. U Słowian Północnych występuje więc szczodrzeniec – jak sama nazwa wskazuje – krzew zimozielony i szczodrogodowy, dzisiaj popularnie nazywany też żarnowcem – co także oddaje jego charakter szczodrogodowy – jako krzewu od-nawiającego – żar – światło i ciepło. Dodatkowo trzeba tu stwierdzić że krzew nie zastępuje drzewa, lecz reperezentuje krzewy, tak samo jemioła nie zastępuje krzewów – to rodzaj rózgi – wiązanki, którą podwiesza się do Podłaźnika. Drzewm szcodrogodowym odwiecznie, prawdopodobnie od wczesnego neolitu jest u Słowian Północnych Jodła – święty dawca pokarmu – Szyszek i Nasion podobnie jak Sosna. Te sprawy są naświetlone dokładnie przeze mnie w drugim tomie „Księgi Tanów – Jesień , Zima” CB ]

Kermes oak. The Kermes Oak was historically important as the only food plant of the Kermes scale insect, from which a red dye called crimson was obtained. Red berries, red dye…

Dąb Kermes. Dąb Kermes był historycznie ważny jako jedyna roślina pokarmowa owada łuskowatego, z którego uzyskano czerwony barwnik zwany szkarłatem. Czerwone jagody, czerwony barwnik…

Cork oak

Dąb korkowy

Holm (Holly) oak

Dąb holm (bezszypułkowy / ostrokrzewowy)

Which of these trees do you think is a more appropriate symbol of the god of agriculture, the god of food, the god of the old Golden Age „when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labor„? Do you thing that it is the one that bears edible acorns like oak, or the one that bears poisonous berries like holly? Who got it wrong, the Romans who misunderstood or forgot the old customs of their forefathers, or us who misinterpreted Roman customs? Or did roman customs change and adopt as they migrated further and further up north where these evergreen oaks are not found and so they had to replace them with what every looked the most like these evergreen oaks, and that is holly tree?

Które z tych drzew jest twoim zdaniem bardziej odpowiednim symbolem boga rolnictwa, boga żywności, boga starego Złotego Wieku, „kiedy ludzie cieszyli się spontaniczną obfitością ziemi bez pracy”? Myślisz, że to ten, który rodzi jadalne żołędzie jak dąb, czy ten, który rodzi trujące jagody jak ostrokrzew? Kto się mylił, Rzymianie, którzy źle zrozumieli lub zapomnieli stare zwyczaje swoich przodków, czy my, którzy źle zinterpretowaliśmy rzymskie zwyczaje? A może rzymskie zwyczaje zmieniły się i przyjęły, gdy migrowali dalej i dalej na północ, gdzie nie można znaleźć tych wiecznie zielonych dębów, więc musieli je zastąpić czymś, co najbardziej przypominało te wiecznie zielone dęby, czyli ostrokrzewem?

Celts

Celtowie

Apparently Druids, the priests of the ancient Celts, also decorated their temples with evergreen boughs as a symbol of everlasting life. The evergreen plant that the Druids used is said to have been Mistletoe. Mistletoe which is said to have been used by Druids actually grows on Oaks. The Druids preached in oak forests, and considered oaks sacred. Young deciduous oaks keep their leaves through the winter. Also a lot of Southern European oaks are evergreen, like the sweet Holm Oak or Holy Oak.

Najwyraźniej druidzi, kapłani starożytnych Celtów, również dekorowali swoje świątynie wiecznie zielonymi gałązkami jako symbolem życia wiecznego. Mówi się, że wiecznie zieloną rośliną używaną przez Druidów była jemioła. Jemioła, o której mówi się, że była używana przez Druidów, w rzeczywistości rośnie na Oaks. Druidzi głosili kazania w lasach dębowych i uważali dęby za święte. Młode dęby liściaste zachowują liście przez całą zimę. Również wiele południowoeuropejskich dębów jest wiecznie zielonych, jak słodki dąb bezszypułkowy lub dąb święty.

Quercus macrolepis has a subspecies known as Quercus ithaburensis (Mount Tabor oak). Quercus ithaburensis is found in Southeastern Europe, from Southeastern Italy across Southern Albania to Greece, and in Southwestern Asia from Turkey South through Lebanon, Israel, and neighbouring Jordan.

Quercus macrolepis ma podgatunek znany jako Quercus ithaburensis (dąb Góry Tabor). Quercus ithaburensis występuje w Europie Południowo-Wschodniej, od południowo-wschodnich Włoch przez południową Albanię po Grecję oraz w Azji Południowo-Zachodniej od Turcji na południe przez Liban, Izrael i sąsiednią Jordanię.

Mount Tabor (Hebrew: הַר תָּבוֹר, Modern Har Tavor Tiberian Har Tāḇôr, Arabic: جبل الطور, Jabal aṭ-Ṭūr, Greek: Όρος Θαβώρ) is located in Lower Galilee, Israel, at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, 11 miles (18 km) west of the Sea of Galilee. It was the site of the Mount Tabor battle between Barak under the leadership of the Israelite judge Deborah, and the army of Jabin commanded by Sisera, in the mid 12th century BC.

Góra Tabor ( hebrajski : הַר תָּבוֹר , współczesny Har Tavor Tiberian Har Tāḇôr , arabski : جبل الطور , Jabal aṭ-Ṭūr , grecki : Όρος Θαβώρ ) znajduje się w Dolnej Galilei, Izraelu, na wschodnim krańcu Doliny Jizreel, 18 km na zachód od Jeziora Galilejskiego. Było to miejsce bitwy na górze Tabor między Barakiem pod dowództwem izraelskiego sędziego Deborah a armią Jabina dowodzoną przez Syserę w połowie XII wieku pne.

It is believed by many Christians to be the site of the Transfiguration of Jesus.The Transfiguration of Jesus is an episode in the New Testament narrative in which Jesus is transfigured (or metamorphosed) and becomes radiant upon a mountain.In these accounts, Jesus and three of his apostles go to a mountain (the Mount of Transfiguration). On the mountain, Jesus begins to shine with bright rays of light. The fact that Christ started shining on the mount Tabor became very significant when you see the acorns of the mount tabor oak:

Wielu chrześcijan uważa, że jest to miejsce Przemienienia Jezusa. Przemienienie Jezusa to epizod w narracji Nowego Testamentu, w którym Jezus zostaje przemieniony (lub przemieniony) i jaśnieje na górze. W tych relacjach Jezus i trzech jego apostołów udaje się na górę (Górę Przemienienia). Na górze Jezus zaczyna świecić jasnymi promieniami światła. Fakt, że Chrystus zaczął świecić na górze Tabor, stał się bardzo znaczący, gdy zobaczysz żołędzie dębu z góry Tabor:

Any sun worshipper would prefer this oak to any other. But these oaks don’t grow in the Northwest of Europe. Where did Celts and Druids come from and who were they if their sacred acorn, the sun acorn, only grew in Southern Mediterranean, in the Balkans including the Greek Islands, in Morocco, and in Levant??? Are the Irish legends about the migration from the Balkans true?

Germanic, Scandinavian

Germanie, Skandynawowie

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, „Tree worship was common among the pagan Europeans and survived their conversion to Christianity in the Scandinavian customs of decorating the house and barn with evergreens at the New Year to scare away the devil and of setting up a tree for the birds during Christmastime.”

Według Encyclopædia Britannica „kult drzew był powszechny wśród pogańskich Europejczyków i przetrwał ich nawrócenie na chrześcijaństwo w skandynawskich zwyczajach dekorowania domu i stodoły wiecznie zielonymi roślinami na Nowy Rok w celu odstraszenia diabła i stawiania drzewa dla ptaków w okresie świątecznym”.

A yule log is a large wooden (oak) log which is burned in the hearth as a part of traditional Yule or modern Christmas celebrations in several European cultures.

Kłoda bożonarodzeniowa (Badniak CB) to duża drewniana (dębowa) kłoda, która jest spalana w palenisku jako część tradycyjnych świąt Bożego Narodzenia lub nowoczesnych obchodów Bożego Narodzenia w kilku kulturach europejskich.

In Scandinavian mythology, the oak was sacred to the thunder god, Thor. Here I would need help in clarifying something. Is there any reference in Norse mythological sources to any tree being used during Winter solstice celebrations? I found some vague references to Yule log.

W mitologii skandynawskiej dąb był poświęcony bogu piorunów Thorowi. Tutaj potrzebowałbym pomocy w wyjaśnieniu czegoś. Czy w nordyckich źródłach mitologicznych jest jakaś wzmianka o jakimkolwiek drzewie używanym podczas obchodów przesilenia zimowego? Znalazłem kilka niejasnych odniesień do kłody / chodaka Yule.

It was apparently a large oak log decorated with sprigs of fir, holly or yew. Runes were carved on it, asking the Gods to protect the people from misfortune. The log was struck by a smith with a hammer, playing the role of Thor the thunder god. The new fire was kindled on log. A piece of the log was saved to protect the home during the coming year and light next year’s fire….

Najwyraźniej była to duża kłoda dębu ozdobiona gałązkami jodły, ostrokrzewu lub cisu. Wyryto na nim runy, prosząc bogów o ochronę ludzi przed nieszczęściem. W kłodę uderzał kowal młotem, wcielając się w rolę Thora, boga piorunów. Nowy ogień rozpalono na polanie. Kawałek kłody został zachowany, aby chronić dom w nadchodzącym roku i rozpalić ogień w przyszłym roku….

But I could not find any concrete reference to any of these customs. Are there any sagas, historical texts, ethnographic records that record any such customs among the Scandinavians? Was Yule log actually part of the Yule celebration in the Scandinavian countries during old pagan times?

Ale nie mogłem znaleźć żadnego konkretnego odniesienia do żadnego z tych zwyczajów. Czy są jakieś sagi, teksty historyczne, zapisy etnograficzne, które odnotowują takie zwyczaje wśród Skandynawów? Czy kłoda Yule rzeczywiście była częścią obchodów Yule w krajach skandynawskich w dawnych czasach pogańskich?

Georgian

Gruzińskie

In Georgia people have their own traditional Christmas tree called Chichilaki, made from dried up hazelnut or walnut branches that are shaved to form a small coniferous tree.

W Gruzji ludzie mają własną tradycyjną choinkę zwaną Chichilaki, wykonaną z suszonych gałęzi orzecha laskowego lub orzecha włoskiego, które są strzyżone, tworząc małe drzewko iglaste.

These pale-colored ornaments differ in height from 20 cm (7.9 in) to 3 meters (9.8 feet). Chichilakis are most common in the Guria and Samegrelo regions of Georgia near the Black Sea, but they can also be found in some stores around the capital of Tbilisi. Sometimes the Christmas tree is hazelnut branch which is carved into a Tree of Life-like shape and decorated with fruits and sweets.

Te blado kolorowe ozdoby różnią się wysokością od 20 cm (7,9 cala) do 3 metrów (9,8 stopy). Chichilaki są najbardziej powszechne w regionach Guria i Samegrelo w Gruzji w pobliżu Morza Czarnego, ale można je również znaleźć w niektórych sklepach w stolicy Tbilisi. Czasami choinką jest gałązka orzecha laskowego, która jest wyrzeźbiona w kształcie Drzewa Życia i ozdobiona owocami i słodyczami.

Slavic Polish

Słowiańska Polska

In Poland there was an old pagan custom of suspending at the ceiling a branch of fir, spruce or pine called Podłaźniczka associated with Koliada the ancient Slavic winter solstice festival. The name Koliada comes from the word „kolo” meaning wheel, spinning circle and representing the spinning of the circle of sun and therefore of life.

W Polsce istniał stary pogański zwyczaj zawieszania pod sufitem gałązki jodły, świerka lub sosny zwanej Podłaźniczką, związany z Koliadą, starosłowiańskim świętem przesilenia zimowego. Nazwa Koliada pochodzi od słowa „kolo” oznaczającego koło, wirujący krąg i reprezentujące wirujący krąg słońca, a więc i życia.

The branches were decorated with apples, nuts, cookies, colored paper, stars made of straw, ribbons and colored wafers. Some people believed that the tree had magical powers that were linked with harvesting and success in the next year. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, these traditions were almost completely replaced by the German custom of decorating the Christmas tree.

Gałęzie ozdobiono jabłkami, orzechami, ciastkami, kolorowym papierem, gwiazdkami ze słomy, wstążkami i kolorowymi opłatkami. Niektórzy wierzyli, że drzewo ma magiczną moc, która wiąże się ze zbiorami i sukcesem w następnym roku. Pod koniec XVIII i na początku XIX wieku te tradycyjne dodatki zostały niemal całkowicie wyparte przez niemiecki zwyczaj ubierania choinki. [Co do rzekomo niemieckiego zwyczaju ubiernaia choinki, chojki, hójki polecam tekst do którego link umieszczam pod tym artykułem CB]

Slavic Serbian and Bulgarian

Słowiańska Serbia i Bułgaria

For the Serbs, all trees have always been considered sacred, but the Oak was and still is the most sacred tree of all. This is why in Serbia oak is also the Christmas tree in a shape of a Christmas log and the Christmas boughs. The tree from which the log and the boughs are cut, has to be a young and straight oak, which is ceremonially felled early on the morning of Christmas Eve.

Dla Serbów wszystkie drzewa zawsze były uważane za święte, ale Dąb był i nadal jest najświętszym drzewem ze wszystkich. Dlatego w Serbii dąb jest także choinką w kształcie bożonarodzeniowej kłody i bożonarodzeniowych konarów. Drzewem, z którego ścina się kłodę i konary, musi być młody i prosty dąb, który jest uroczyście ścinany wczesnym rankiem w Wigilię Bożego Narodzenia.

[Chodzi tutaj o Badniak o którym piszemy w Księdze Tanów. Tu tylko uwaga dla przypomnienia, że w Polsce równie świętym drzewem jest Lipa, no i oczywiście jak u Serbów – wszystkie drzewa są święte CB]

It is then brought into the house and placed on the fire on the evening of Christmas Eve where it is supposed to burn through the whole night. The felling, preparation, bringing in, and laying on the fire, are surrounded by elaborate rituals, with many regional variations. This is the central tradition in Christmas celebrations among the Orthodox Serbs and Bulgarians, much like a yule log in some other European traditions. In Serbian language the oak Christmas tree is called Badnjak and in Bulgarian language it is called Budnik. This literally means the awoken one, the one that stays awake, that keeps you awake. In Serbian the Christmas Eve is called Badnje Veče and in Bulgarian the name for Christmas Eve is Budni Večer which means „The evening when we stay awake”. Serbs believed that the sun is a living being which has a lifespan of one year. On the winter solstice night, the old sun dies and on the winter solstice morning the new sun is born. The burning of the Christmas tree log ritual is the remnant of the ancient wither solstice ritual performed to help rekindle the sun and to insure that the sun’s fire starts blazing and producing heat again. The ceremony also includes the feast which is organized to celebrate the birth of the new sun, the young sun. Christmas itself is in Serbian called Božić (Cyrillic: Божић, pronounced [ˈbɔ̌ʒitɕ]), which is the diminutive form of the word bog („god”), and can be translated as „young god”. The whole ritual is also linked to fertility, particularly grain fertility, bread fertility. In Serbian tradition we find the direct link between the old bread source (oak and acorn) and new bread source (grain). This can even be seen from the fact that both oak branches and grain sheaves and hay are used in ceremonies.

Następnie wnosi się go do domu i podpala w wieczór wigilijny, gdzie ma palić się przez całą noc. Wyrąb, przygotowanie, wniesienie i rozpalenie ognia są otoczone wyszukanymi rytuałami, z wieloma regionalnymi odmianami. Jest to centralna tradycja obchodów Bożego Narodzenia wśród prawosławnych Serbów i Bułgarów, podobnie jak dziennik bożonarodzeniowy w niektórych innych tradycjach europejskich. W języku serbskim dębowa choinka nazywa się Badnjak, a w języku bułgarskim Budnik. To dosłownie oznacza przebudzonego, tego, który nie śpi, który nie pozwala ci zasnąć. Po serbsku Wigilia nazywa się Badnje Veče, a po bułgarsku Wigilia to Budni Večer, co oznacza „wieczór, kiedy nie śpimy”. Serbowie wierzyli, że słońce jest żywą istotą, której żywotność wynosi jeden rok. W noc przesilenia zimowego stare słońce umiera, a w poranek przesilenia zimowego rodzi się nowe słońce. Rytuał palenia kłody choinki jest pozostałością starożytnego rytuału przesilenia, wykonywanego w celu ponownego rozpalenia słońca i upewnienia się, że ogień słoneczny ponownie zacznie płonąć i wytwarzać ciepło. Ceremonia obejmuje również ucztę organizowaną dla uczczenia narodzin nowego słońca, młodego słońca. Samo Boże Narodzenie nazywa się po serbsku Božić ( cyrylica : Божић, wymawiane [ˈbɔ̌ʒitɕ] ), co jest zdrobnieniem słowa torfowisko („bóg”) i można je przetłumaczyć jako „młody bóg”. Cały rytuał wiąże się też z płodnością, a szczególnie płodnością zboża, płodnością chleba. W tradycji serbskiej znajdujemy bezpośredni związek między starym źródłem chleba (dąb i żołądź) a nowym źródłem chleba (ziarno). Świadczy o tym nawet fakt, że podczas ceremonii używa się zarówno gałęzi dębowych, jak i snopów zbożowych oraz siana.

I will dedicate a whole post to this Christmas tradition (Badnjak – Yule log).

Tej świątecznej tradycji (Badnjak – kłoda bożonarodzeniowa) poświęcę cały post.

As you can see, the choice of trees used as Winter Solstice (Christmas) trees is very consistent. It is Oak (acorns), Pine, Spruce, Fir (pine cones), Walnut, Hazelnut. You can also add to this list Chestnut, as chestnuts are also roasted for Winter Solstice (Christmas). These are all the large seed bearing trees, the trees which provided the humans on the northern hemisphere with the first starch food, first bread during the Golden Age time. These trees were the main sources of food for the Mesolithic cultures living in the Oak – Pine ring of the northern hemisphere, the Garden of Eden, and they must have been worshipped as gods. That this was the case can be seen from the worship of the Oaks which still exists in Serbia and the adoration of the Oak tree itself during the Winter Solstice (Christmas) ceremonies. The worship of these trees continued even when the grain replaced the acorns and pine nuts as the main starch source. The main old „bread” trees, Oak and Pine, Spruce, Fir are still used as central symbols in the Winter Solstice (Christmas) agricultural grain fertility festival. This shows that the transition from the old tree bread to the new field bread was slow and long, allowing the preservation of the old tree fertility customs albeit thinly disguised as grain fertility customs. Like a Serbian Badnjak oak wrapped in a wheat sheaf…

Jak widać, wybór drzew wykorzystywanych jako drzewka przesilenia zimowego (bożonarodzeniowego) jest bardzo spójny. Jest to dąb (żołędzie), sosna, świerk, jodła (szyszki), orzech włoski, orzech laskowy. Możesz również dodać do tej listy Kasztan, ponieważ kasztany są również pieczone na Przesilenie Zimowe (Boże Narodzenie). Są to wszystkie duże drzewa rodzące nasiona, drzewa, które dostarczyły ludziom na półkuli północnej pierwszego pożywienia skrobiowego, pierwszego chleba w czasie Złotego Wieku. Drzewa te były głównym źródłem pożywienia dla kultur mezolitycznych żyjących w pierścieniu dębowo-sosnowym półkuli północnej, Ogrodzie Eden, i musiały być czczone jak bogowie. O tym, że tak było, świadczy kult dębów, który nadal istnieje w Serbii oraz adoracja samego dębu podczas ceremonii przesilenia zimowego (Boże Narodzenie). Kult tych drzew trwał nawet wtedy, gdy zboże zastąpiło żołędzie i orzeszki piniowe jako główne źródło skrobi. Główne stare „chlebowe” drzewa, dąb i sosna, świerk i jodła, są nadal używane jako centralne symbole podczas święta płodności zboża podczas przesilenia zimowego (Boże Narodzenie). Pokazuje to, że przejście od starego chleba drzewnego do nowego chleba polnego było powolne i długie, co pozwoliło zachować zwyczaje płodności starego drzewa, choć słabo zamaskowane zwyczajami płodności zboża. Jak serbski dąb Badnjak zawinięty w snop pszenicy…

[Powyższy fragment wskazuje po raz kolejny – i to z zupełnmie innej strony dochodzac do tego samego wniosku – że Chójna, Choina Słowian Pólnocnych nie jest żadnym zapożyczeniem od Niemców ani Skandynawów, ale jest wprost przeniesionym znad Dunaju prastarym, paleolitycznym i wczesno-neolitycznym, zwyczajem uświęcania Drzewa Chlebowego – CB]

Wesołych Świąt.

Merry Christmas.