Eating acorns (Jedzenie żołędzi)

© by Goran Pavlovic © tłumaczenie by Czesław Białczyński

How did people start to eat acorns? Well pretty much in the same way people started to eat all the other plants. A good hunter knows its prey well. He knows its habits including its diet. Animals are the easiest to catch while they are distracted by food. So people observed animals eating plants. The animals would come to the same places every year at the same time and eat the same plants. So people would use this knowledge to ambush the animals on their feeding grounds. But hunting is not easy. Animals don’t like to be killed and eaten. And even when they are eating themselves they are constantly on their guard. So hunters often end up with empty hands. After an unsuccessful hunt, and while thinking about what he could eat to stop his stomach rumbling, some bright spark among the hunters probably had a train of thoughts that went like this:

Jak ludzie zaczęli jeść żołędzie? Cóż, mniej więcej w ten sam sposób ludzie zaczęli jeść wszystkie inne rośliny. Dobry myśliwy dobrze zna swoją ofiarę. Zna jej zwyczaje, w tym dietę. Zwierzęta najłatwiej złapać, gdy rozprasza je jedzenie. Więc ludzie obserwowali zwierzęta jedzące rośliny. Zwierzęta przychodziły co roku w te same miejsca o tej samej porze i zjadały te same rośliny. Więc ludzie używali tej wiedzy do zasadzek na zwierzęta na ich żerowiskach. Ale polowanie nie jest łatwe. Zwierzęta nie lubią być zabijane i zjadane. I nawet gdy same się pożerają, cały czas mają się na baczności. Dlatego myśliwi często kończą z pustymi rękami. Po nieudanym polowaniu zastanawiając się, co mogliby zjeść, żeby nie burczało im w brzuchu, jakiś jasny chochlik-iskierka wśród myśliwych prawdopodobnie zajarzył i miał ciąg myśli, który wyglądał mniej więcej tak:

These animals eat this plant all the time. They must like it a lot. And the animals seem to be OK after eating the plant. I mean they look positively happy. This plant must be good to eat. I am hungry. Ah feck it. I’ll give it a try…

Te zwierzęta jedzą tę roślinę przez cały czas. Musi im się to bardzo podobać. A zwierzęta wydają się być w porządku po zjedzeniu rośliny. Mam na myśli, że wyglądają na zadowolone i szczęśliwe. Ta roślina musi być dobra do jedzenia. Jestem głodny. Ach pieprzyć to. Dam temu szansę...

Munch Munch Munch….

Hey Grunt what are you chewing?

This plant that the animals eat all the time. Its good, its different…Try it…

Munch Munch Munch….(everyone is munching)

Hey chief, do you think we can get away with bringing this home for dinner instead of meat? I mean my wife was looking forward to a roast…And she gets really cranky when she is hungry…

Sure, we’ll tell them its good for their health and their hair. Come on boys, lets grab a few handfuls of this plant each and lets go home. Its getting late…

The rest is prehistory…

Mniam Mniam Mniam….

Hej Grunt co żujesz?

Tę roślinę, którą zwierzęta jedzą cały czas. Jest dobra, inna… Spróbuj… Mniam Mniam Mniam….(wszyscy przeżuwają)

Hej szefie, myślisz, że ujdzie nam na sucho przyniesienie tego do domu na obiad zamiast mięsa? To znaczy moja żona nie mogła się doczekać pieczeni… A kiedy jest głodna, robi się naprawdę marudna…

Jasne, powiemy im, że to dobre dla ich zdrowia i włosów. Chodźcie chłopcy, weźmy po kilka garści tej rośliny i chodźmy do domu. Robi się późno…

Reszta to prehistoria…

People still hunted and ate the animals, but would also pick and eat the plant that the animal ate. And so salad was invented, which if you are a Serbian, is still best eaten with lots of meat, but can in extreme circumstances be eaten by itself.

Ludzie nadal polowali i jedli zwierzęta, ale także zrywali i jedli roślinę, którą zjadało zwierzę. I tak powstała sałatka, którą jeśli jesteś Serbem, nadal najlepiej jeść z dużą ilością mięsa, ale w skrajnych przypadkach można ją jeść samą.

I mean don’t get me wrong. People were always omnivores, scavengers, opportunistic hunter gatherers, eating anything that was not fast enough to run away, whether they were plants or animals. They did learn a lot about food from animals though, by observing and copying their behaviour. Well smart people did. The stupid ones tried things that no one ate and died…

Nie zrozum mnie źle. Ludzie zawsze byli wszystkożercami, padlinożercami, oportunistycznymi łowcami-zbieraczami, zjadającymi wszystko, co nie było wystarczająco szybkie, aby uciec, niezależnie od tego, czy były to rośliny, czy zwierzęta. Nauczyli się jednak wiele o jedzeniu od zwierząt, obserwując i kopiując ich zachowanie. Cóż, mądrzy ludzie to robili. Głupcy próbowali rzeczy, których nikt nie jadł i umierali…

Even learning from animals doesn’t always work though. Some plants which can be eaten by animals taste horrible. Some can be digested by animals but are indigestible to humans. Some can have harmful affects on human health and some can be outright poisonous to humans. But that’s evolution for you…Hit and miss.

Nawet uczenie się od zwierząt nie zawsze działa. Niektóre rośliny, które mogą jeść zwierzęta, smakują okropnie. Niektóre mogą być trawione przez zwierzęta, ale są niestrawne dla ludzi. Niektóre mogą mieć szkodliwy wpływ na zdrowie ludzi, a niektóre mogą być wręcz trujące dla ludzi. Ale to jest twoja ewolucja… Trafianie i pudłowanie.

Of course the bright spark in the above story could have been a woman as well. According to the available anthropological data, hunter gatherer societies did not have strict division of labour. Pretty much everyone did everything more or less. So women were probably part of the hunting and gathering bands and it could have been a woman who first decided to try „that thing that the animals are eating”…

So how did people start eating acorns? Well people hunted rodents, squirrels, deer, wild boar, jay birds, ducks, woodpeckers and all these animals loved eating acorns. They loved acorns so much that acorns made up 25% of their autumn diet. Particularly wild pigs were fond of acorns and herds of these animals could be seen in the oak forests every autumn with their snouts stuck to the ground hovering up the so called acorn blanket. And getting fat and juicy.

Jak więc ludzie zaczęli jeść żołędzie? Cóż, ludzie polowali na gryzonie, wiewiórki, jelenie, dziki, sójki, kaczki, dzięcioły i wszystkie te zwierzęta uwielbiały jeść żołędzie. Uwielbiały żołędzie tak bardzo, że żołędzie stanowiły 25% ich jesiennej diety. Szczególnie dzikie świnie upodobały sobie żołędzie i każdej jesieni w dębach można było zobaczyć stada tych zwierząt z przyklejonymi do ziemi pyskami unoszącymi się nad tzw. kocem żołędziowym. I robi się tłusta i soczysta.

So every autumn hunters would hunt in oak forests trying to catch animals which were feasting on the fallen acorns. Eventually someone somewhere must have tried acorns himself. And if we know that most acorns are bitter and pretty horrible raw, our experimental acorn eater probably went „blah, yuck, horrible, bitter” spitting the half chewed acorn out. But a smart hunter gatherer would soon noticed that squirrels sometimes eat only the upper half of the acorn and throw away the lower part, and he would have wondered why.

Dlatego każdej jesieni myśliwi polowali w dębowych lasach, próbując złapać zwierzęta, które żerowały na opadłych żołędziach. W końcu ktoś gdzieś musiał sam spróbować żołędzi. A jeśli wiemy, że większość żołędzi jest gorzka i dość okropna na surowo, nasz eksperymentalny zjadacz żołędzi prawdopodobnie powiedział „bla, fuj, okropny, gorzki”, wypluwając na wpół przeżuty żołądź. Ale bystry myśliwy-zbieracz szybko zauważyłby, że wiewiórki czasami zjadają tylko górną połowę żołędzia i odrzucają dolną, i zacząłby się zastanawiać, dlaczego.

Well now we know that this is because the tannin, which makes the acorn bitter, tends to be in the bottom half of the acorn near the cap. But our hunter gatherer would just know that maybe squirrels know something that he doesn’t. He would then try the same tactics and would realise that you can eat acorn tops and discard acorn bottoms and avoid most of the yucky bitter stuff. He would also notice that the acorn nut is covered with some sort of dark brown skin, which is very bitter. So our smart hunter gatherer would carefully peel it off the nut before eating it. Now that our hunter gatherer was concentrated on the acorn eating habits of animals, he would also notice that squirrels and other animals prefer certain types of acorns which grew on certain types of oak trees. The animals would always eat them first, and only go on to eat the other types of acorns when their favourite acorns were all eaten. A good hunter gatherer would conclude that there must be something special about these acorns that makes the animals like them so much. So our experimental acorn eater would try these acorns and would find out that they were a lot less bitter or not bitter at all. So he would eat a good few of them and would collect a few to bring to his family. A good hunter gatherer would look at the acorn shape, and he would look at the tree under which he found the acorns, and would remember them, so that next time he would know how to distinguish the sweet acorns from the bitter ones. Then next day the whole family would probably be in the forest collecting and eating acorns. Hunter gatherers never throw away easy food.

They would still kill and eat animals that eat acorns, like pigs for instance, but they would also collect acorns and eat them too. This is how stuffing was invented which is a great accompaniment to pork… 🙂

Nadal zabijali i jedli zwierzęta, które jedzą żołędzie, na przykład świnie, ale zbierali też żołędzie i je jedli. Tak powstał farsz, który jest świetnym dodatkiem do wieprzowiny… 🙂

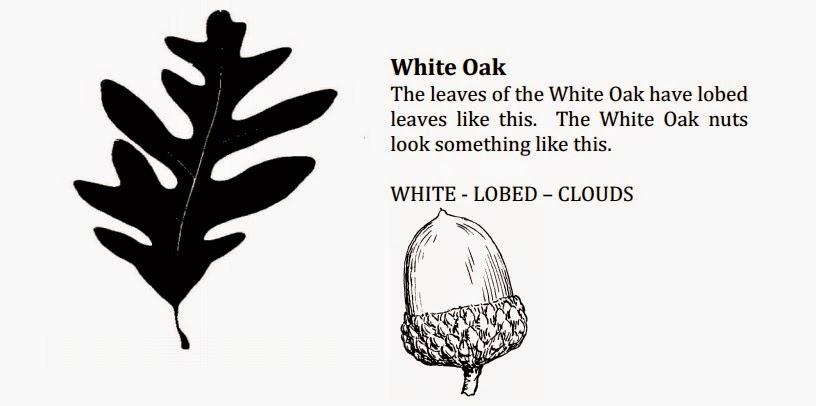

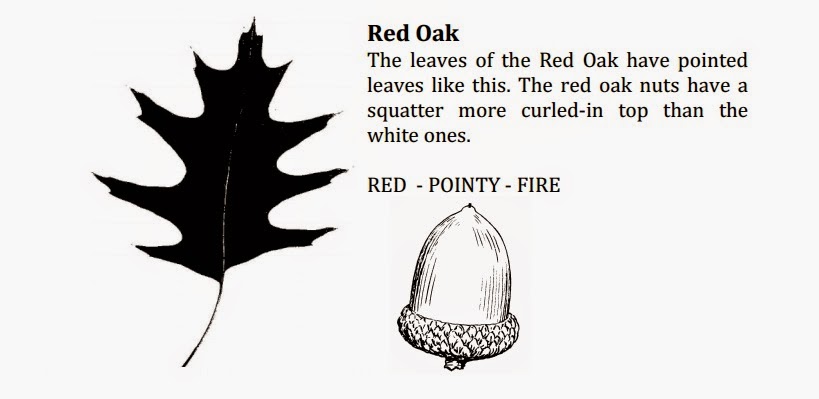

Eventually a good hunter gatherer would realise that there were two distinct types of oaks and acorns:

W końcu dobry myśliwy-zbieracz zdałby sobie sprawę, że istnieją dwa różne rodzaje dębów i żołędzi:

The white oaks whose acorns mature in 6 months and taste sweet or slightly bitter; The inside of the acorn shell is hairless. The bark is light in colour, gray to light gray. The leaves mostly lack a bristle on their lobe tips, which are usually rounded.

Białe dęby, których żołędzie dojrzewają w ciągu 6 miesięcy i smakują słodko lub lekko gorzko; Wnętrze skorupy żołędzi jest bezwłose. Kora jest koloru jasnego, szarego do jasnoszarego. Liście przeważnie nie mają włosia na końcach, które są zwykle zaokrąglone.

The red and black oaks whose acorns mature in 18 months and taste bitter to very bitter. The inside of the acorn’s shell can be hairless but is in most cases woolly. The bark darker in colour. Its leaves typically have sharp lobe tips, with bristles at the lobe tip.

Czerwone i czarne dęby, których żołędzie dojrzewają w ciągu 18 miesięcy i mają gorzki lub bardzo gorzki smak. Wnętrze skorupy żołędzia może być bezwłose, ale w większości przypadków jest wełniane. Kora ma ciemniejszy kolor. Jego liście mają zazwyczaj ostre końcówki, z włosiem na końcu płata.

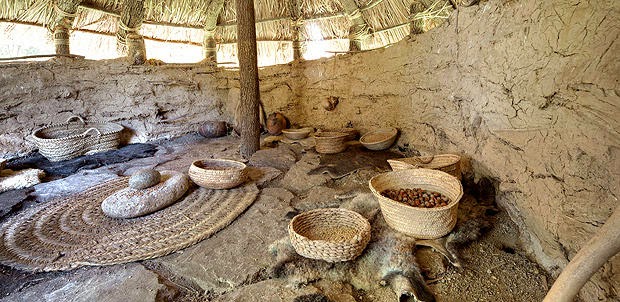

A smart hunter gatherer would also notice that some animals which eat acorns, like squirrels and jay birds, collect the acorns in the autumn, store them in holes in the ground and in trees and then eat them during the winter. Someone must have caught a squirrel getting acorns from one of its stashes in the middle of winter. If they tried the acorns from the stash, they would have quickly realised that they were perfectly edible. Now not too many things are edible in the middle of winter, so this must have been a revelation. If I collect acorns in the autumn and store them somewhere, then I will also have something good to eat throughout the winter. Eventually the whole clan would start collecting acorns every autumn. Gathering would take place between September and December. It is a simple job that could be done in three ways: picking the ripe acorns from the ground, causing them to fall by knocking them down from the tree with a long stick and then picking them from the ground, or by climbing the tree and cutting the tips of the branches with ripe acorns using sickles. The second two methods were used to prevent the animals get to the good acorns before people. All three methods were attested in the ethnographic studies. Oaks produce so many acorns that people could in 2 – 3 weeks easily collect enough acorns to last them 2 to 3 years. The question then was how to transport all these acorns from the oak forest to the settlement and how and where to store the acorns. So people invented baskets, like these ones reconstructed from the remains of baskets which were found in the La Draga lake-dwelling site from the Iberian Peninsula which was occupied at least twice between 5300 and 5000 BC by people of Carded Ware Culture. The baskets which contained acorns.

Sprytny myśliwy-zbieracz zauważyłby również, że niektóre zwierzęta żywiące się żołędziami, takie jak wiewiórki i sójki, zbierają żołędzie jesienią, przechowują je w dziurach w ziemi i na drzewach, a następnie zjadają je zimą. Ktoś musiał złapać wiewiórkę zbierającą żołędzie z jednego ze swoich schowków w środku zimy. Gdyby spróbowali żołędzi ze schowka, szybko zorientowaliby się, że są doskonale jadalne. Teraz niewiele rzeczy nadaje się do jedzenia w środku zimy, więc to musiała być rewelacja. Jeśli jesienią zbiorę żołędzie i gdzieś je schowam, to przez całą zimę też będę miał coś dobrego do jedzenia. W końcu cały klan zaczął zbierać żołędzie każdej jesieni. Zbiórka odbywałaby się między wrześniem a grudniem. Jest to prosta czynność, którą można wykonać na trzy sposoby: zebrać dojrzałe żołędzie z ziemi, zebrać je strącając z drzewa długim kijem, albo wspinając się na drzewo i obcinając czubkki gałęzi z dojrzałymi żołędziami za pomocą sierpów. Te dwie ostatnie metody stosowano, aby zwierzęta nie dostały się do dobrych żołędzi przed ludźmi. Wszystkie trzy metody zostały potwierdzone w badaniach etnograficznych. Dęby produkują tak dużo żołędzi, że ludzie mogliby w ciągu 2-3 tygodni z łatwością zebrać ich wystarczającą ilość na 2-3 lata. Powstaje więc pytanie, jak przetransportować te wszystkie żołędzie z dębowego lasu do osady oraz jak i gdzie je przechowywać. Wymyślono więc koszyki, takie jak te zrekonstruowane z pozostałości koszy znalezionych w miejscu zamieszkania jeziora La Draga z Półwyspu Iberyjskiego, które było co najmniej dwukrotnie zasiedlone między 5300 a 5000 pne przez ludzi z kultury ceramiki zgrzebnej. Kosze, w których były żołędzie.

I believe that people new how to make cordage and how to weave many thousands of years before they made the first basket. The archaeological data confirms that too. Why? Because they didn’t need baskets. Baskets are a solution for a particular problem. Baskets are only useful for collecting bitty things in large quantities, transporting them from the collection point to the storage point and then storing them at the storage point. And this situation did not arise until Upper Paleolithic, the time when we find the first permanent settlements of people who collected large quantities of fish, shellfish, snails, acorns and nuts, the bitty things that you can collect, transport and store in baskets. I will dedicate my whole next post to this subject.

Wierzę, że ludzie nauczyli się robić powrozy i tkać wiele tysięcy lat przed zrobieniem pierwszego kosza. Potwierdzają to również dane archeologiczne. Dlaczego? Ponieważ nie potrzebowali koszy. Kosze są rozwiązaniem konkretnego problemu. Kosze są przydatne tylko do zbierania drobiazgów w dużych ilościach, transportu ich z punktu zbiórki do punktu składowania, a następnie przechowywania ich w punkcie składowania. I taka sytuacja nie zaistniała aż do górnego paleolitu, kiedy to spotykamy pierwsze stałe osady ludzi, którzy zbierali duże ilości ryb, skorupiaków, ślimaków, żołędzi i orzechów, drobiazgów, które można zbierać, przewozić i przechowywać w koszach. Temu tematowi poświęcę cały następny wpis.

But paradoxically, while people put considerable effort and ingenuity into inventing dry storage for acorns above the ground, we find in the archaeological and ethnographic data that acorns were mostly stored in bulk in pits dug into the damp ground. Why did people start storing acorns in this way? Because squirrels and jays, apart from storing acorns in hollow trees and basket like nests, also stored them by burying them in holes in the ground. If people tried acorns from few different squirrel caches, of which some were stored in hollow trees (raised dry baskets) and some in holes in the ground, they would soon realise that the ones which were buried in wet ground, particularly wet clay at the edge of streams, tasted sweater, less bitter. So people soon started digging pits in the ground and burying acorns in them. Acorns which are buried from few weeks to few years, taste sweater because they get leached in contact with the damp ground. The acorns stored like this get dark in colour and are very good for roasting.

Ale paradoksalnie, podczas gdy ludzie wkładali znaczny wysiłek i pomysłowość w wynalezienie suchego przechowywania żołędzi nad ziemią, w danych archeologicznych i etnograficznych stwierdzamy, że żołędzie były przeważnie przechowywane luzem w dołach wykopanych w wilgotnej ziemi. Dlaczego ludzie zaczęli przechowywać żołędzie w ten sposób? Bo wiewiórki i sójki, oprócz przechowywania żołędzi w dziuplach i koszyczkowatych gniazdach, przechowywały je również zakopując je w dołkach w ziemi. Gdyby ludzie spróbowali żołędzi z kilku różnych kryjówek wiewiórczych, z których część przechowywana była w dziuplach (podniesione suche kosze), a część w dziurach w ziemi, szybko zorientowaliby się, że te zakopane w wilgotnej ziemi, szczególnie mokrej glinie na brzegu strumienia, smakowały lepiej, były mniej gorzkie. Wkrótce więc ludzie zaczęli kopać doły w ziemi i zakopywać w nich żołędzie. Żołędzie, które są zakopane od kilku tygodni do kilku lat, mają słodszy smak, ponieważ w kontakcie z wilgotną ziemią ulegają wypłukaniu. Tak przechowywane żołędzie ciemnieją i bardzo dobrze nadają się do pieczenia.

Recent research, based on ethnographic data from America and Sardinia, has proven that clay and particularly red clay, when mixed with unleached acorn meal would, remove up to 80% of tannic acid from acorn meal through chemical and catalytic processes which occur during baking. You can read papers about this type of leaching in these two articles:

Niedawne badania, oparte na danych etnograficznych z Ameryki i Sardynii, dowiodły, że glina, a zwłaszcza glinka czerwona, po zmieszaniu z niewyługowaną mączką żołędziową usunie do 80% kwasu garbnikowego z mączki żołędziowej poprzez procesy chemiczne i katalityczne zachodzące podczas pieczenia. Wiadomości na temat tego rodzaju wymywania można przeczytać w tych dwóch artykułach:

„Traditional detoxification of acorn bread with clay” by Timothy Johnsa & Martin Duquettea

„Detoxification and mineral supplementation as functions of geophagy” by Timothy Johnsa & Martin Duquettea

„Tradycyjna detoksykacja chleba żołędziowego za pomocą gliny” autorstwa Timothy’ego Johnsa i Martina Duquettea „Detoksykacja i suplementacja mineralna jako funkcje geofagii” autorstwa Timothy’ego Johnsa i Martina Duquettea

In 2002 an experiment in pit storing of hazelnuts was performed in England. The experiment was intended to prove that storage pits found in the Mesolithic site of Mount Sandel, Northern Ireland were capable of storing hazelnuts for a prolonged period of time. The experiment has demonstrated that hazelnuts will store in pits for 18 weeks, even in conditions that are less than ideal, meaning fully or partially submerged in mud and water, and that the use of a basket lining helps prevent the hazelnuts from spoiling whilst in the water. The experiment demonstrates that the underground storage of hazelnuts is neither a complicated nor a difficult task, but to store hazelnuts successfully in pits does require an understanding of the pit site environment and that responding to this environment in a constructive way ensures success.

W 2002 roku w Anglii przeprowadzono eksperyment dołowego przechowywania orzechów laskowych. Eksperyment miał na celu udowodnienie, że doły magazynowe znalezione (jamy zasobowe CB) w mezolitycznym miejscu Mount Sandel w Irlandii Północnej były w stanie przechowywać orzechy laskowe przez dłuższy czas. Eksperyment wykazał, że orzechy laskowe mogą być przechowywane w jamach zasobowych przez 18 tygodni, nawet w warunkach dalekich od idealnych, co oznacza całkowite lub częściowe zanurzenie w błocie i wodzie, oraz że zastosowanie wyściółki kosza pomaga zapobiegać psuciu się orzechów laskowych w wodzie. Eksperyment pokazuje, że podziemne przechowywanie orzechów laskowych nie jest ani skomplikowanym, ani trudnym zadaniem, ale pomyślne przechowywanie orzechów laskowych w dołach wymaga zrozumienia środowiska w miejscu wyrobiska i tego, że reagowanie na to środowisko w konstruktywny sposób zapewnia sukces.

The results of this experiment were published in the article: „Assumptive holes and how to fill them, The contribution presents first results of experiments on pit storage of hazelnuts” by Penny Cunningham

Wyniki tego eksperymentu zostały opublikowane w artykule: „Przypuszczalne dziury i jak je wypełnić. Wykład przedstawia pierwsze wyniki eksperymentów dotyczących przechowywania orzechów laskowych w jamach zasobowych” autorstwa Penny Cunningham.

The thing is the original Mesolithic pits from Mount Sandel were probably used not for storing hazelnuts but for storing acorns.

Rzecz w tym, że oryginalne mezolityczne doły z góry Sandel prawdopodobnie służyły nie do przechowywania orzechów laskowych, ale do przechowywania żołędzi.

According to „A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill, similar type of storage pits lined with baskets and dug in a wet waterlogged ground were found in early neolithic sites in China filled with acorns, and next to dwellings where grind stones were found containing traces of acorns. What is interesting is that the archaeological records from different acorn eating cultures from around the world point to a deliberate choice of waterlogged terrains for these acorn pits, as if people wanted these pits to be flooded and for the acorns to be submerged in water. Why? Because it is the water in the soil that removes the poisonous and bitter tannin from the acorns. And the more water flaws through the pit, the quicker the tannin gets removed. How did people discover this?

Według „A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” Anne P. Underhill podobny typ dołów magazynowych wyłożonych koszami i wykopanych w podmokłym gruncie znaleziono na wczesnych neolitycznych stanowiskach w Chinach i były one wypełnione żołędziami, a obok mieszkań, w których używano kamieni szlifierskich także znaleziono ślady żołędzi. Co ciekawe, zapisy archeologiczne z różnych kultur zjadaczy żołędzi z całego świata wskazują na celowy wybór podmokłych terenów dla tych dołów żołędziowych, tak jakby ludzie chcieli, aby te doły zostały zalane, a żołędzie zanurzone w wodzie. Dlaczego? Ponieważ to woda w glebie usuwa z żołędzi trujące i gorzkie garbniki. Im więcej wody przepływa przez dół, tym szybciej tanina zostaje usunięta. Jak ludzie to odkryli?

Oak forests often grow on flood planes and are often found growing next to ponds or bayous.

Lasy dębowe często rosną na terenach zalewowych i często rosną obok stawów lub zalewów.

Sometimes acorns would fall into the water instead of falling on the dry ground. Our smart hunter gatherer would soon notice that some of the acorns would float on water while most would sink to the bottom. Being smart and inquisitive, both charactheristics of a good hunter gatherer, he would soon realise that the acorns that didn’t sink were either infected by fungus, rot or worms and were not good to eat. So our hunter gatherer would start using this as test, to quickly separate good acorns from bad ones. He would simply pour all the acorns that he had collected from the ground into the water and would discard all the ones that didn’t sink.This is very important because if you store good and bad acorns together they would soon all be spoiled.

Czasami żołędzie wpadały do wody zamiast spadać na suchą ziemię. Nasz sprytny łowca-zbieracz szybko zauważyłby, że niektóre żołędzie unoszą się na wodzie, podczas gdy większość opada na dno. Będąc bystrym i dociekliwym, co jest cechami dobrego myśliwego-zbieracza, szybko zdałby sobie sprawę, że żołędzie, które nie tonęły, były albo zainfekowane przez grzyby, zgniliznę, albo robaki i nie nadawały się do jedzenia. Więc nasz łowca-zbieracz zacząłby używać tego jako testu, aby szybko oddzielić dobre żołędzie od złych. Po prostu wsypywał do wody wszystkie żołędzie, które zebrał z ziemi, i wyrzucał te, które nie utonęły. Jest to bardzo ważne, ponieważ jeśli przechowujesz razem dobre i złe żołędzie, wkrótce wszystkie się zepsują.

Sometimes oak forests get completely submerged for a short period of time during the autumn and spring rains. After the waters recede, the ground would stay covered with wet acorns. If our hunter gatherer ate some of these corns which were submerged in water for a few weeks, he would notice that they tasted much sweater than acorns that he collected from the dry ground and which were not soaked in water. If our hunter gatherer was a smart hunter gatherer, he would soon realise that it is the fact that the acorns were soaked in water for a period of time which made acorns sweater. So he would soon start soaking acorns in water himself to try to make them sweater. This was done in acorn leaching pits like the ones discovered in archaeological sites in both America (Sauvie Island native American settlements) and Japan (Higashimyo Jomon settlements).

Czasami podczas jesiennych i wiosennych deszczy lasy dębowe są całkowicie zalewane na krótki czas. Gdy wody opadną, ziemia pozostanie pokryta mokrymi żołędziami. Gdyby nasz łowca-zbieracz zjadł trochę tych żoołędzi zanurzonych w wodzie na kilka tygodni, odnotowałby że smakowały one dużo bardziej niż żołędzie które zebrał z suchej ziemi a które nie były zamoczone w wodzie. Gdyby nasz łowca-zbieracz był sprytnym łowcą-zbieraczem, szybko zdałby sobie sprawę, że to iż żołędzie były moczone w wodzie przez pewien czas, sprawiło, że żołędzie są słodsze. Wkrótce więc sam zacząłby moczyć żołędzie w wodzie, aby spróbować zrobić z nich słodkie. Dokonywano tego w dołach do ługowania żołędzi, takich jak te odkryte na stanowiskach archeologicznych w Ameryce ( osady rdzennych Amerykanów na wyspie Sauvie) i Japonii (osady Higashimyo Jomon ).

The data about the american leaching pits was published in the article „Balanophagy in the Pacific Northwest: The Acorn-Leaching Pits at the Sunken Village Wetsite and Comparative Ethnographic Acorn Use” by Bethany Mathews

Dane o amerykańskich dołach do ługowania zostały opublikowane w artykule Bethany Mathews „Balanophagy in the Pacific Northwest: The Acorn-Leaching Pits at the Sunken Village Wetsite and Comparative Ethnographic Acorn Use„.

The data about the Japanese leaching pits was published in the article „Recent Japan-Northwest coast wet site exchange„, by Dale Croes

Dane dotyczące japońskich dołów do ługowania zostały opublikowane w artykule Dale’a Croesa „Recent Japan-Northwest coast wet site exchange„.

He would see that acorns would release black juice which made water taste bitter and he would soon realise that it is this dark juice that needs to be taken out of the acorns in order to make them sweat. And so water leaching of acorns was invented. Eventually people realised that shelling, crushing and grinding the acorns before leaching them would intensify tannin removal and shorten the leaching time from couple of months to few hours. So you could store your acorns dry into baskets, which is good if you want to carry them around from place to place, and then leach them when you need them.

Zobaczyłby, że żołędzie wydzielają czarny sok, który sprawia, że woda ma gorzki smak i wkrótce zdałby sobie sprawę, że to właśnie ten ciemny sok trzeba wyciągnąć z żołędzi, aby się wyługowały. I tak wynaleziono wodne ługowanie żołędzi. W końcu ludzie zdali sobie sprawę, że łuskanie, miażdżenie i mielenie żołędzi przed ich ługowaniem zintensyfikuje usuwanie garbników i skróci czas ługowania z kilku miesięcy do kilku godzin. Możesz więc przechowywać suche żołędzie w koszach, co jest dobre, jeśli chcesz je przenosić z miejsca na miejsce, a następnie wypłukiwać, kiedy ich potrzebujesz.

So to do this type of quick leaching you need to first shell the acorns. Slowly dried acorns are easier to shell because the acorn shrinks and the thin brown bitter covering sticks to the shell so both are easily removed. Breaking the acorn shell and separating the acorn from the shell is the most difficult part of acorn food preparation. Acorns have an elastic shell that resists slow sideways pressure. The best way to break the acorns shell is to put the flat end (the side that used to have the cap) on a firm surface and hit the pointy end with a stone. I believe that it is this process of breaking the acorn shells that often resulted in broken and crushed acorns. I believe that people leaching acorns would have gathered whole and broken acorns and leached them together. And the smart hunter gatherer would soon notice that the crushed pieces leached quicker, and that smaller the bits are the quicker the leaching is. So people started crushing all the acorns before leaching. But they also noticed that just whacking the acorns with a stone scatters the bits everywhere. However if you gently break the shell, take the acorn out, place it on a flat stone, and then press the acorn with another stone and move the pressing stone in a scraping, grinding motion over the acorn, all the bits will stay on the bottom flat stone. And this is how grinders were invented.I will dedicate one of my next post to the grinders.

Aby więc wykonać ten rodzaj szybkiego wypłukiwania, musisz najpierw obrać żołędzie. Wolno suszone żołędzie są łatwiejsze do łuskania, ponieważ żołądź kurczy się, a cienka brązowa gorzka powłoka przykleja się do skorupy, dzięki czemu można ją łatwo usunąć. Łamanie skorupy żołędzia i oddzielanie żołędzia od skorupy jest najtrudniejszą częścią przygotowywania żywności z żołędzi. Żołędzie mają elastyczną skorupę, która jest odporna na powolny nacisk boczny. Najlepszym sposobem na rozbicie skorupy żołędzi jest położenie płaskiego końca (strony, na której była czapka) na twardej powierzchni i uderzenie kamieniem w ostry koniec. Uważam, że to właśnie ten proces rozbijania łusek żołędzi często powodował połamane i zmiażdżone żołędzie. Wierzę, że ludzie wypłukujący żołędzie zbierali całe i połamane żołędzie i wypłukiwali je razem. A sprytny zbieracz-łowca szybko zauważyłby, że pokruszone kawałki wypłukują się szybciej, a im mniejsze są kawałki, tym szybciej następuje wypłukiwanie. Więc ludzie zaczęli miażdżyć wszystkie żołędzie przed wypłukiwaniem. Ale zauważyli również, że samo walenie w żołędzie kamieniem rozrzuca kawałki wszędzie. Jeśli jednak delikatnie rozbijesz skorupę, wyjmij żołądź, połóż go na płaskim kamieniu, a następnie dociśnij żołądź innym kamieniem i przesuń kamień dociskowy ruchem trącym, mielenia po żołędziu. Wtedy wszystkie kawałki żołędzia pozostaną na powierzchni dolnego płaskiego kamienia. I tak powstały młynki. Jeden z moich kolejnych postów poświęcę młynkom.

Now that acorns are shelled and crushed they can be leached by getting them into contact with water. This is done by submerging the acorns into a container containing fresh water in proportion 1 part acorn 3 parts water or more water. The acorns will sink to the bottom and start leaching straight away turning the water dark. Then you wait for a while (up to a day). You then pour out the tanned water and pour in new fresh water and repeat the procedure until the water stops turning dark or until acorns stop tasting biter. Simple. Well actually not so simple if you are a hunter gatherer from Mesolithic. Watertight container were hard to find at that time, because pottery was still not invented…The closest thing to a pot was a pit dug into a waterlogged ground. Exactly what people used for pit leaching. But changing water in a pit is quite a task, so it is much easier to just fill the pit with acorns and water, forged about the whole thing for few months and let the ground water slowly leach the tannins into the ground. Exactly how people used pit leaching. Because of all this I believe that pit leaching is the earliest type of leaching practiced by people.

Teraz, gdy żołędzie są wyłuskane i zmiażdżone, można je wypłukiwać, zanurzając je w wodzie. Odbywa się to poprzez zanurzenie żołędzi w pojemniku zawierającym świeżą wodę w proporcji 1 część żołędzi na 3 części wody lub więcej wody. Żołędzie opadną na dno i natychmiast zaczną się wypłukiwać, powodując ciemnienie wody. Następnie czekasz chwilę (do jednego dnia). Następnie wylewasz garbowaną wodę i wlewasz nową świeżą wodę i powtarzasz procedurę, aż woda przestanie ciemnieć lub dopóki żołędzie nie przestaną gorzko smakować. Proste. Cóż, właściwie nie jest to takie proste, jeśli jesteś łowcą-zbieraczem z mezolitu. Trudno było wówczas znaleźć wodoszczelne naczynie, ponieważ ceramika wciąż nie została wynaleziona… Najbliższą garnkowi rzeczą był dół wykopany w podmokłym gruncie. Dokładnie to jest to, czego ludzie używali do ługowania – dołu. Ale zmiana wody w dołku to nie lada sztuka, więc znacznie łatwiej jest po prostu napełnić dołek żołędziami i wodą, wykonywać to wszystko przez kilka miesięcy i pozwolić wodzie gruntowej powoli wypłukiwać garbniki do gruntu. Dokładnie tak ludzie wykonywali wtedy proces ługowania. Z tego powodu uważam, że wypłukiwanie jest najwcześniejszym rodzajem ługowania praktykowanym przez ludzi.

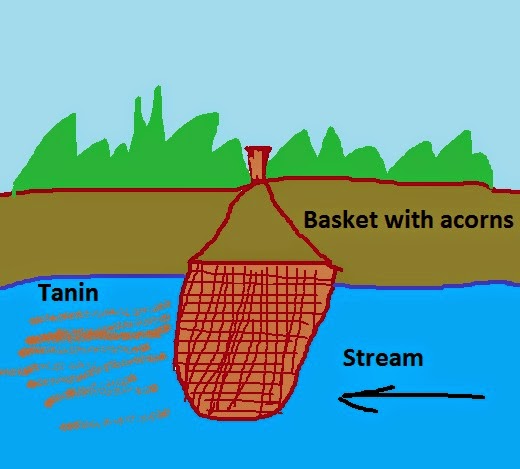

Once relatively fine woven baskets were invented, it became possible to leach whole acorns or large enough bits of acorns in baskets in couple of days rather than in couple of months. You needed a deep basket, some strong cordage, a stake and a stream. You fill the basket with a shelled acorns whole or roughly crashed acorns, tie it to the stake which is stuck into the bank and then lower the basket into the stream. You leave it there for couple of days and the flowing stream water will leach the acorns. Like this:

Po wynalezieniu stosunkowo drobno tkanych koszy stało się możliwe wypłukiwanie całych żołędzi lub wystarczająco dużych kawałków żołędzi w koszach w ciągu kilku dni, a nie kilku miesięcy. Potrzebny był głęboki kosz, mocne liny, kołek i strumień. Napełnia się kosz łuskanymi żołędziami w całości lub z grubsza pokruszonymi żołędziami, przywiązuje się go do słupka wbitego w brzeg, a następnie opuszcza kosz do strumienia. Zostawisz go tam na kilka dni, a płynąca woda wypłucze żołędzie. Jak tu:

Again the finer the basket, the finer the acorns can be ground and the faster the leaching process will be. From ethnographic data we know that this type of leaching was very common too.

Ponownie, im drobniejsze oczka kosza, tym drobniej żołędzie można zmielić i tym szybszy będzie proces wypłukiwania. Z danych etnograficznych wiemy, że ten rodzaj wypłukiwania był również bardzo powszechny.

There is another way to leach acorns in a pit without having to take water out. You make a pit in such way that it can slowly drain by itself. You can achieve this by building a mound from a porous material, like sand, and then dig a pit in the mound, by hollowing the center of the mound. You then line the pit with leaves or fine basket or textile and pour the finely ground acorns into the pit. It is important that acorns are ground as finely as possible in order to speed up dissolving of tannin. Then you pour the water over the acorns, fill the pit and wait until the water drains away. As the water slowly drains it dissolves and takes away the tannic acid with it. Then you pour water over the acorns again filling the pit and repeat the whole process. You do that until the acorns are not bitter any more. This artificial pit acorn leaching was recorded by ethnographers in America and it looks like this:

Istnieje inny sposób wypłukiwania żołędzi w jamie bez konieczności wypompowywania wody. Robisz dół w taki sposób, aby woda powoli mogła odpłynąć. Możesz to osiągnąć, budując kopiec z porowatego materiału, takiego jak piasek, a następnie wykopując dół w kopcu, wydrążając środek kopca. Następnie wyłóż dołek liśćmi, drobnym koszykiem lub tkaniną i wlej do niego drobno zmielone żołędzie. Ważne jest, aby żołędzie były jak najdrobniej zmielone, aby przyspieszyć rozpuszczanie garbników. Następnie zalej żołędzie wodą, napełnij dół i poczekaj, aż woda odpłynie. Gdy woda powoli spływa, rozpuszcza i zabiera ze sobą kwas garbnikowy. Następnie ponownie zalewamy żołędzie wodą, wypełniając nieckę i powtarzamy cały proces. Robisz to, dopóki żołędzie nie będą już gorzkie. To sztuczne wypłukiwanie żołędzi zostało zarejestrowane przez etnografów w Ameryce i wygląda tak:

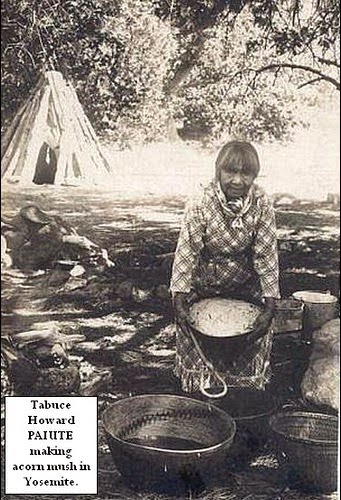

Native American people of the Northern Sierra Mewuk (Miwok) used this leaching technique using flowing fresh water and sand pit as a leaching pit:

Rdzenni Amerykanie z północnej Sierra Mewuk (Miwok) stosowali tę technikę ługowania, wykorzystując płynącą świeżą wodę i piaskownicę jako dół do ługowania:

Traditionally they would go to the nearest stream and find a sandy area. There they would form out a leaching bed and spread out the acorn flour on top of the clean sand. They would then form a channel bringing the water to the bed and allowing a steady stream to flow over the acorn. Cedar bows were used to allow the incoming water to flow evenly over the flour. Leaching took at least 8-10 hours, depending on how much and how deep the flour was. After 8 hours a taste test was done to determine if the leaching was finished. When the acorn meal was ready, it was picked up off the leaching bed. At that stage the acorn meal resembled wet clay. You would pick the globs of it and gently wash off any sand with water. Because acorn is high in oils not much adheres to it…

Tradycyjnie szli do najbliższego strumienia i znajdowali piaszczysty teren. Tam tworzyli dół do ługowania i rozrzucali mąkę żołędziową na czystym piasku. Następnie tworzono kanał doprowadzający wodę dodołu i umożliwiający stały przepływ strumienia przez żołędzie. Aby umożliwić równomierny przepływ napływającej wody po mące używano drewna cedrowego. Wymywanie trwało co najmniej 8-10 godzin, w zależności od ilości i głębokości mąki. Po 8 godzinach wykonywano test smakowy w celu określenia, czy ługowanie zostało zakończone. Kiedy mączka z żołędzi była gotowa, wyjmowano ją ze złoża ługującego. Na tym etapie mączka żołędziowa przypominała mokrą glinę. Trzeba było zbierać żołędziowe bryłki i delikatnie zmywać piasek wodą. Ponieważ żołędzie są bogate w oleje, niewiele do nich przylega…

Leaching acorns in this way takes many hours if the acorns were finely ground and requires a lot of work. This is not ideal. People are lazy and laziness is the mother of all invention. So one day someone decided to see what happens if a hot water was poured over the ground acorns. What happened was that acorns submerged in hot water leached a lot faster, taking only two to three hours to lose their bitterness. On the above picture you can see all the equipment needed for this hot water leaching process:

Wypłukiwanie żołędzi w ten sposób zajmuje wiele godzin, jeśli żołędzie były drobno zmielone i wymaga dużo pracy. To nie jest idealne. Ludzie są leniwi, a lenistwo jest matką wszystkich wynalazków. Pewnego dnia ktoś postanowił sprawdzić, co się stanie, jeśli zmielone żołędzie polejemy gorącą wodą. Stało się tak, że żołędzie zanurzone w gorącej wodzie wypłukiwały się znacznie szybciej, tracąc gorycz w ciągu zaledwie dwóch do trzech godzin. Na powyższym zdjęciu widać cały sprzęt potrzebny do tego procesu ługowania gorącą wodą:

The fire at the woman’s right is used to heat stones. The hot stones are dropped into a watertight bowl (in this case a watertight basket) using wooden grabbers (lying in front of the pit). Boiling basket is coated with a thin layer of acorn gruel. The gruel works like a glue that coats the basket so that no water would leak from it. This is because of the high oil and protein content of acorns which work as adhesives and fillers. Hot stones heat the water up, and the hot water is then poured over the acorn flour using a smaller bowl. The water is poured over a bundle of twigs to lessen the force of the water and distribute the water evenly over the flour. The stones used for water heating has to be carefully chosen so that they don’t fracture during the continuous heating and cooling. The best stones for this purpose are basalt stones as the don’t shatter under thermal pressure. How did people get the idea to use hot stones for heating water is still a mystery to me. Any ideas?

Ogień po prawej stronie kobiety służy do podgrzewania kamieni. Gorące kamienie wrzuca się do wodoszczelnej miski (w tym przypadku wodoszczelnego kosza) za pomocą drewnianych chwytaków (leżących przed jamą). Wrzący koszyk jest pokryty cienką warstwą kleiku żołędziowego. Kleik działa jak klej, który pokrywa kosz, aby woda z niego nie wyciekała. Wynika to z wysokiej zawartości oleju i białka w żołędziach, które działają jako kleje i wypełniacze. Gorące kamienie podgrzewają wodę, a następnie wlewa się gorącą wodę do mąki żołędziowej za pomocą mniejszej miski. Wodę wylewa się na wiązkę gałązek, aby zmniejszyć jej siłę i równomiernie rozprowadzić wodę po mące. Kamienie używane do podgrzewania wody muszą być starannie dobrane, aby nie pękały podczas ciągłego ogrzewania i chłodzenia. Najlepszymi kamieniami do tego celu są kamienie bazaltowe, ponieważ nie pękają pod ciśnieniem termicznym. Skąd ludzie wpadli na pomysł wykorzystania gorących kamieni do podgrzewania wody, wciąż pozostaje dla mnie zagadką. Jakieś pomysły?

In addition to using hot water to speed up the process of dissolving the tannin, some smart hunter gatherers also used wood ash to induce chemical reactions which transform tannic acid into harmless chemicals. Early ethnobotanist Huron Smith (1923, pg 66) documented the Menominee method of processing various oak species: „The hulls were flailed off after parching, and the acorn was boiled till almost cooked. The water was then thrown away. Then to fresh water, two cups of wood ash were added. The acorns were put into a net and were pulled out of the water after boiling in this. The third time, they were simmered to clear them of lye water. Then they are ground into meal with mortar and pestle, then sifted in a birch-bark sifter.”

Oprócz używania gorącej wody w celu przyspieszenia procesu rozpuszczania garbników, niektórzy inteligentni zbieracze myśliwi używali również popiołu drzewnego do wywoływania reakcji chemicznych, które przekształcają kwas garbnikowy w nieszkodliwe chemikalia. Dawny etnobotanik Huron Smith (1923, s. 66) udokumentował metodę obróbki różnych gatunków dębów przez Menominów: „Po wysuszeniu łuski otrzepywano, a żołądź gotowano prawie do ugotowania na miękko. Następnie wodę wylewano. Potem do świeżej wody, dodawano dwie szklanki popiołu drzewnego. Żołędzie wkładano do siatki i po ugotowaniu w niej wyciągano z wody. Za trzecim razem gotowano na wolnym ogniu, aby oczyścić je z wody ługowej. Następnie rozcierano je na mączkę w moździerzu i tłuczkiem, a następnie przesiewano na przesiewaczu z kory brzozowej”.

There are couple of things that need to know when using water for acorn leaching:

Jest kilka rzeczy, które należy wiedzieć, używając wody do wypłukiwania żołędzi:

You have to use either only cold water or only hot water for leaching. If you mix cold and hot water or if you put acorns into cold water and then heat the water, the tannin in the acorns will be bound to the acorn meat permanently and you will not be able to remove it. I bet that took a bit of time to figure out. The temperature of water with which you leach the acorns is very important. Heating water over 73 degrees Celsius precooks the starch in the acorn. Cold processing and low temperatures under 65 degrees Celsius does not cook the starch. Acorn meal that was leached in cold water thickens when cooked, hot-water leached acorn meal does not thicken when cooked. Also, when you leach the acorns in hot water you also boil off the oil with the tannins, reducing acorn meal nutrition. So you should choose the leaching water temperature depending on what you want to use acorns for. If you are going to leach and roast whole acorns for snacking then boiling is fine. If you are going to use the acorn for flour it should be cold processed, or you will have to add a binder. But bread was never the intended end product of the acorn meal preparation. In fact, as it is evident from the ethnographic data, the intended end product was an acorn mush, gruel, porridge or an acorn soup. We know from the ethnographic data that even when cereals replaced acorn as the main starch food, mush, gruel, porridge, soup was still the main way people prepared and ate grain.

Do ługowania musisz używać tylko zimnej wody lub tylko gorącej wody. Jeśli zmieszasz zimną i gorącą wodę lub jeśli włożysz żołędzie do zimnej wody, a następnie podgrzejesz wodę, garbnik w żołędziach zostanie trwale związany z miąższem żołędzi i nie będziesz mógł go usunąć. Założę się, że zajmowało to trochę czasu. Bardzo ważna jest temperatura wody, w której wypłukuje się żołędzie. Podgrzewanie wody powyżej 73 stopni Celsjusza powoduje wstępne gotowanie skrobi w żołędziu. Obróbka na zimno i niskie temperatury poniżej 65 stopni Celsjusza nie gotują skrobi. Mączka żołędziowa wypłukana w zimnej wodzie gęstnieje po ugotowaniu, mączka żołędziowa wypłukana gorącą wodą nie gęstnieje po ugotowaniu. Ponadto, kiedy ługujesz żołędzie w gorącej wodzie, odparowujesz również olej z garbnikami, zmniejszając wartość odżywczą mączki z żołędzi. Należy więc wybrać temperaturę wody do ługowania w zależności od tego, do czego chcemy wykorzystać żołędzie. Jeśli zamierzasz ługować i upiec całe żołędzie na przekąskę, gotowanie jest w porządku. Jeśli zamierzasz użyć żołędzi do zrobienia mąki, to powinny być przetworzone na zimno lub będziesz musiał dodać spoiwo. Ale chleb nigdy nie był zamierzonym produktem końcowym przygotowania mąki z żołędzi. W rzeczywistości, jak wynika z danych etnograficznych, zamierzonym produktem końcowym była papka żołędziowa, kleik, owsianka lub zupa żołędziowa. Z danych etnograficznych wiemy, że nawet gdy zboża zastąpiły żołędzie jako główne pożywienie skrobiowe, papka, kleik, kasza, zupa nadal były głównym sposobem przyrządzania i spożywania zboża.

The ethnobotanist Huron Smith in his work on Menominee method of processing various oak species also says that: after the acorn meal was leached in hot water three times, the fourth time, the meal is cooked in soup stock of deer meat until finished and ready to eat, or made into mush with bear oil seasoning. The old Indians never made pie, but the Menomini now make pie of them.

Etnobotanik Huron Smith w swojej pracy Metoda Menominów przetwarzania różnych gatunków dębu mówi również, że: po trzykrotnym wypłukaniu mączki żołędziowej w gorącej wodzie, po raz czwarty mączkę gotuje się w bulionie z mięsa jelenia, aż będzie ugotowana i gotowa do spożycia. Wtedy można ją jeść lub zrobić papkę z przyprawą z oleju niedźwiedziego. Dawni Indianie nigdy nie robili ciasta, ale teraz Menomini robią z nich ciasto.

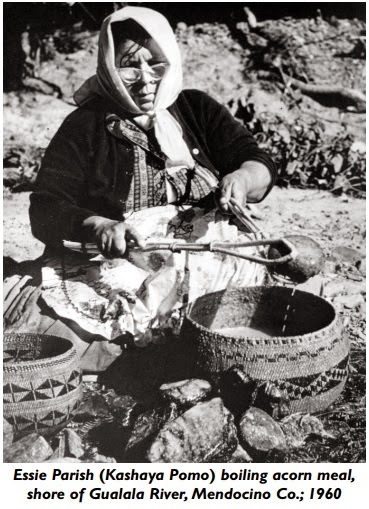

So aftre leaching, a fresh water and acorn meal were mixed together with some herbs and meat stock and boiled into a thin soup or thicker mush. There were two ways that this type was food was cooked. One way was to boil the mush in a clay or stone pot over a fire. But that had to wait until pottery was invented.

Tak więc po wypłukaniu świeżą wodę i mączkę żołędziową mieszano z ziołami i bulionem mięsnym i gotowano w rzadkiej zupie lub gęstszej papce. Były dwa sposoby przyrządzania tego typu potraw. Jednym ze sposobów było gotowanie papki w glinianym lub kamiennym garnku nad ogniem. Ale na to trzeba było poczekać, aż wynaleziono ceramikę.

The other way to boil food was by stone boiling in baskets or some other type of watertight but not fire resistant container, such as wooden bowls or containers. This is a very interesting subject and I will dedicate one of my next post to it.

Innym sposobem gotowania żywności było gotowanie na kamieniu w koszach lub innym rodzaju wodoszczelnych, ale nie ognioodpornych pojemników, takich jak drewniane miski lub garnki. To bardzo ciekawy temat i poświęcę mu jeden z kolejnych postów.

The hot stone cooking was done in this way. Hot rocks the size of tennis balls were heated by fire. Then, they were put into baskets or wooden bowls or containers filled with water and acorn meal. The stones were stirred in the baskets gently and slowly with a wooden paddle or looped stirrer. When the mixture began to boil it was cooked, exactly like when you make a cereal porridge. The stones were then removed from the basket with wooden tongs.

W ten sposób odbywało się gotowanie na gorącym kamieniu. Gorące skały wielkości piłek tenisowych były ogrzewane przez ogień. Następnie wkładano je do koszy lub drewnianych misek lub pojemników wypełnionych wodą i mączką żołędziową. Kamienie w koszach delikatnie i powoli mieszano drewnianą łopatką lub mieszadłem pętlowym. Kiedy mieszanina zaczęła się gotować, była gotowana, dokładnie tak, jak robi się owsiankę zbożową. Następnie kamienie wyjmowano z kosza za pomocą drewnianych szczypiec.

It is interesting that the hot water leaching cooks the acorn meal at the same time, turning it into a sort of porridge or a thick soup which then only needs one boil to be ready to eat. Exactly like the oat meal of today which is precooked and then dried.

Co ciekawe, wypłukiwanie gorącą wodą jednocześnie gotuje mączkę żołędziową, zamieniając ją w coś w rodzaju owsianki lub gęstej zupy, która potrzebuje tylko jednego zagotowania, aby była gotowa do spożycia. Dokładnie tak, jak dzisiejsza mąka owsiana, która jest wstępnie gotowana, a następnie suszona.

There is an old story called „Stone Soup„. The story involves a stranger coming to a village, building a hearth and placing a pot of water over it. He (or she) puts in stones and invites others to taste the stone soup. The stranger invites others to add an ingredient, and pretty soon, Stone Soup is a collaborative meal full of tasty things. Not to mention a stone or two. Is this a memory of the most ancient way of cooking in water, invented as a byproduct of leaching acorns with hot water?

Jest taka stara historia zatytułowana „Kamienna Zupa”. Historia opowiada o nieznajomym przybywającym do wioski, budującym palenisko i stawiającym na nim garnek z wodą. On (lub ona) wkłada kamienie i zaprasza innych do spróbowania kamiennej zupy. Nieznajomy zaprasza innych do dodania składnika i wkrótce Kamienna Zupa to wspólny posiłek pełen smacznych rzeczy. Nie mówiąc już o kamieniu czy dwóch. Czy to wspomnienie najdawniejszego sposobu gotowania w wodzie, wymyślonego jako produkt uboczny ługowania żołędzi gorącą wodą?

Meat doesn’t need to be boiled. It can be roasted on a spit quite easily. Root vegetables and chestnuts can be roasted on hot coals. Greens and fruit can be eaten raw and so can hazelnuts, almonds and all the other nuts, all except acorns. Acorns are the first type of food which benefited from cooking, boiling in water. Did people invent stone boiling and cooking in water while trying to leach acorns in hot water?

Mięsa nie trzeba gotować. Można je dość łatwo upiec na rożnie. Warzywa korzeniowe i kasztany można upiec na rozżarzonych węglach. Warzywa i owoce można jeść na surowo, podobnie jak orzechy laskowe, migdały i wszystkie inne orzechy, z wyjątkiem żołędzi. Żołędzie to pierwszy rodzaj żywności, który skorzystał na gotowaniu, gotowaniu w wodzie. Czy ludzie wymyślili gotowanie i kamienie do gotowania w wodzie, próbując wypłukiwać w gorącej wodzie żołędzie?

Stone boiling was not possible until the invention of watertight containers such as watertight baskets, stone, wood and clay bowls. And there is no evidence that these containers were in existence before the Younger Dryas. There is evidence that people ate acorns even before Younger Dryas but they could have just eaten the sweet acorns either raw or roasted in the fire, in the same way you would roast chestnuts. The burning of the acorn shells and the presence of wood ash would leach the small amount of tannins present in sweet acorns, and would make them sweet and goot do eat. But as I said already, it is only during the Younger Dryas that we see emergence of the first settled communities which were heavily relying on acorns as their staple starch food. These people collected a lot of acorns, stored them and then used them as food all year round. And at the same time we see emergence of basketry, pottery, grinding stones, wooden and stone utensils. Why, if not for processing acorns? One bad thing about storing acorns is that the more tannin the acorns have the longer they stay fresh. Sweet acorns are usually eaten first and bitter acorns are stored for the winter. And to be able to eat bitter acorns, the leaching and cooking technologies had to be invented. All these are „sure signs of the Neolithic”. Did processing acorns inspire the transition from Mesolithic to Neolithic?

Gotowanie w kamieniu nie było możliwe aż do wynalezienia wodoszczelnych pojemników, takich jak wodoszczelne kosze, kamienne, drewniane i gliniane miski. I nie ma dowodów na to, że pojemniki te istniały przed młodszym dryasem. Istnieją dowody na to, że ludzie jedli żołędzie jeszcze przed młodszym dryasem, ale mogli po prostu jeść słodkie żołędzie na surowo lub pieczone w ogniu, w taki sam sposób, w jaki piecze się kasztany. Spalanie łusek żołędzi i obecność popiołu drzewnego wypłukiwałaby niewielką ilość garbników obecnych w słodkich żołędziach i sprawiłaby, że byłyby słodkie i nadawałyby się do jedzenia. Ale jak już powiedziałem, dopiero podczas młodszego dryasu obserwujemy pojawienie się pierwszych osiadłych społeczności, które w dużym stopniu polegały na żołędziach jako podstawowym pożywieniu skrobiowym. Ci ludzie zbierali dużo żołędzi, przechowywali je, a następnie używali ich jako pożywienia przez cały rok. Jednocześnie obserwujemy pojawienie się wyrobów plecionkarskich, garncarskich, kamieni szlifierskich, naczyń drewnianych i kamiennych. Dlaczego, jeśli nie do przetwarzania żołędzi? Ważną rzeczą w przechowywaniu żołędzi jest to, że im więcej garbników mają żołędzie, tym dłużej pozostają świeże. Słodkie żołędzie są zwykle spożywane jako pierwsze, a gorzkie są przechowywane na zimę. A żeby móc jeść gorzkie żołędzie, trzeba było wynaleźć technologie wypłukiwania i gotowania. Wszystko to uznaje się za „pewne oznaki neolitu”. Czy przetwarzanie żołędzi zainspirowało przejście od mezolitu do neolitu?

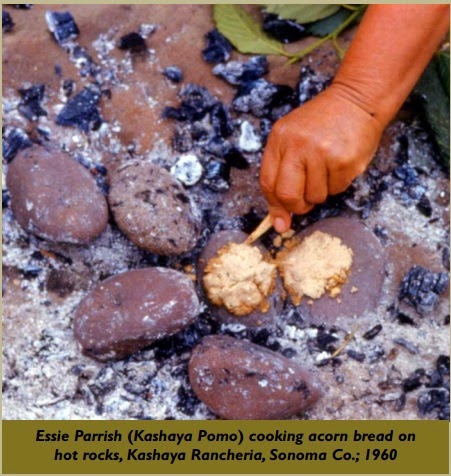

In the end how did the bread get invented? I believe by accident, as a byproduct of stone cooking of acorn porridge. According to the ethnographic data from America, the stones which were used for boiling acorn porridge were after boiling removed from the basket with wooden tongs. The mush that dried onto the rocks was a special treat that children liked to peel off and eat. These pieces were called „acorn chips.” If these acorn chips was so popular it was just a matter of time before these chips stopped being a byproduct and were deliberately made.

W końcu, jak wynaleziono chleb? Myślę, że przez przypadek, jako produkt uboczny gotowania kaszy żołędziowej na kamieniu. Według danych etnograficznych z Ameryki kamienie, w których gotowano owsiankę żołędziową, po ugotowaniu wyjmowano z kosza drewnianymi szczypcami. Papka, która wyschła na skałach, była specjalnym przysmakiem, który dzieci lubiły obierać i jeść. Kawałki te nazywano „chipsami żołędziowymi”. Jeśli te chipsy żołędziowe były tak popularne, to tylko kwestia czasu, zanim te chipsy przestaną być produktem ubocznym i zostaną celowo wyprodukowane.

And this is how bread was invented. The only difference between acorn chips and acorn bread is in thickness and size. Once you realize that a lump of thick acorns mush can be baked into acorn bread all that was left to do is to find the best and easiest way to bake the bread without burning it. Here are some possible ways in which you can do it.

I tak powstał chleb. Jedyną różnicą między plackami żołędziowymi a chlebem żołędziowym jest grubość i rozmiar. Kiedy już zdasz sobie sprawę, że grudkę gęstej papki z żołędzi można upiec na chleb żołędziowy, pozostało tylko znaleźć najlepszy i najłatwiejszy sposób na upieczenie chleba bez jego przypalania. Oto kilka możliwych sposobów, w jakie możesz to zrobić.