Linkardstown cists

Linkardstown cists are so named after first excavated example at Linkardstown in Co. Carlow. The book „Early Ireland: An Introduction to Irish Prehistory” By Michael J. O’Kelly, Claire O’Kelly describe Linkardstown Cists like this:

Komory z Linkardstown zostały tak nazwane od pierwszego odkrytego okazu w Linkardstown w hrabstwie Carlow.W książce „Early Ireland: An Introduction to Irish Prehistory” autorstwa Michaela J. O’Kelly’ego, Claire O’Kelly opisuje kopce z Linkardstown w następujący sposób:

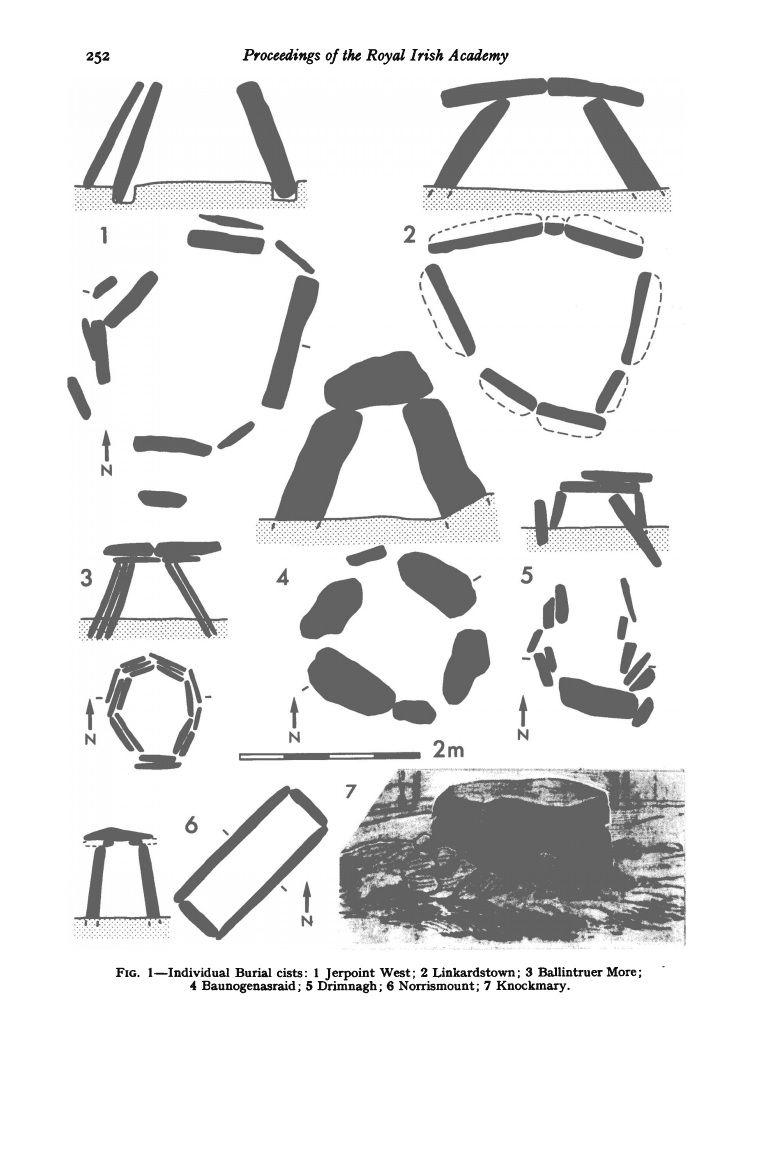

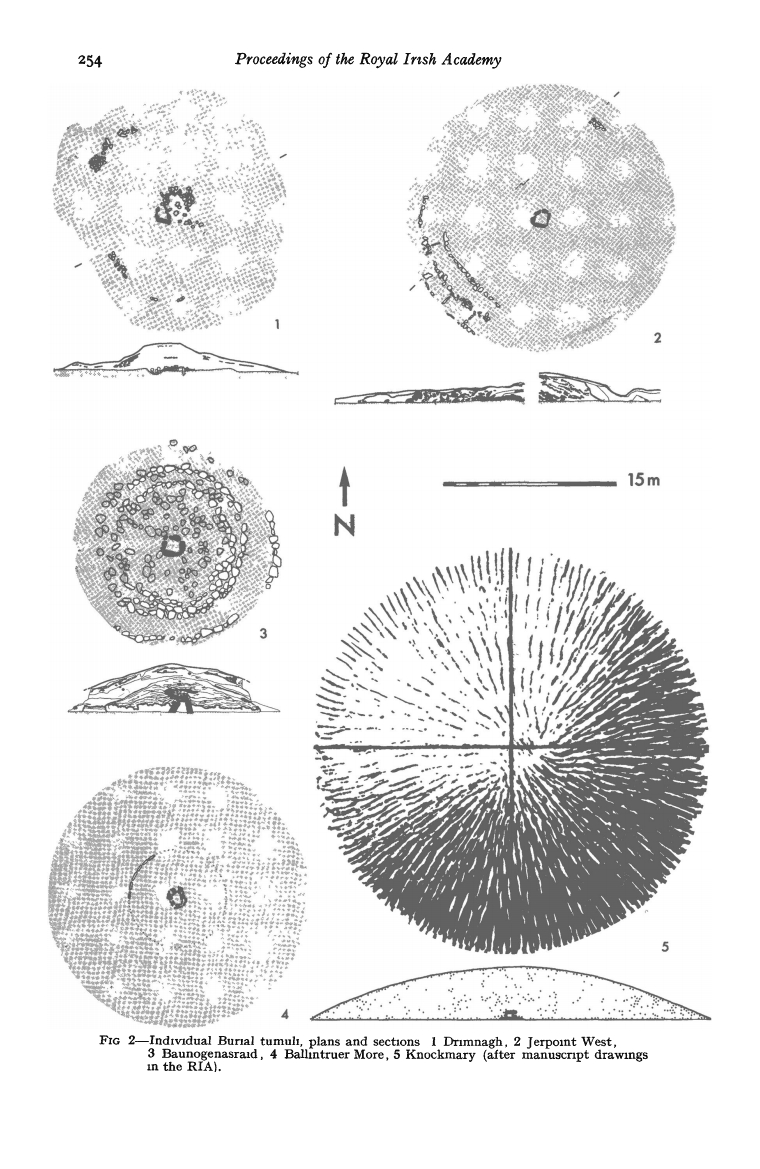

They are built from large slabs or boulders which were arranged on the ground surface, generally in polygonal plan. The original Linkardstown Cists from county Carlow measured 2m X 2.3m at the ground level, but much smaller examples are known, some of them less than a meter in length and width. The side slabs were slanted inwards so that the dimensions at the top were less than at the ground level . All spaces between the side slabs were usually infilled with smaller pieces of stone and other slabs were placed against the outside. A capstone or capstones closed the top.

The normal burial consisted of one or two male bodies, sometimes flexed or crouched.

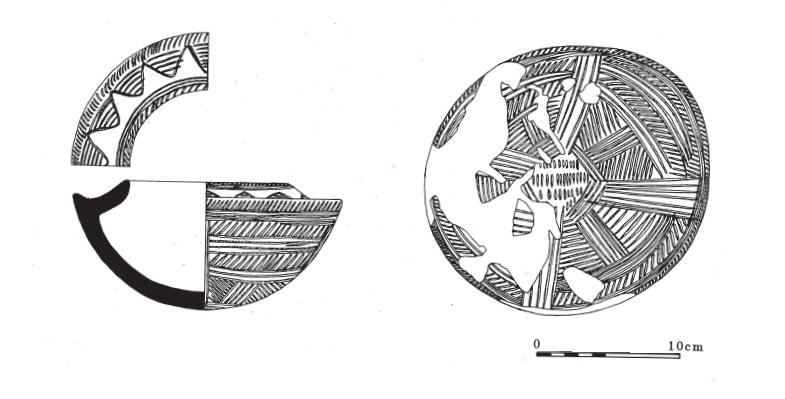

The above two pictures are taken from the „Irish Decorated Neolithic Pottery” by M. Herity. The reason why this book talks about the Linkardstown cists is because some, but not all Linkardstown cists contain round bottomed, highly decorated pots. The pots are shouldered and the ornament consists of channeled grooves, executed with a blunt point in geometric panel, a series of oblique strokes being frequently employed.

Powyższe dwa zdjęcia pochodzą z „Irish Decorated Neolithic Pottery” autorstwa M. Herity’ego. Powodem, dla którego ta książka mówi o komorach z Linkardstown, jest to, że niektóre, ale nie wszystkie komory z Linkardstown zawierają okrągłodenne, bogato zdobione garnki. Naczynia są barkowe, a ornament składa się z rowków kanałowych, wykonanych tępym punktakiem w geometrycznym panelu, często stosuje się serię ukośnych pociągnięć.

This is an example of one of these decorated pots. This one is from the tumulus located at Ballintruer More, Co Wicklow

To przykład jednego z tych zdobionych garnków. Ten pochodzi z kopca znajdującego się w Ballintruer More, Co Wicklow

In „An archaeological reconsideration of solar mythology” by Karlene Jones-Bley we read that „the common elements of these vessels are rayed or starred motifs in combination with a cruciform pattern all found on the base of the vessels…”. In same Linkardstown cists, a plain round bottomed shouldered bowl is found with the decorated pots.

W „An archaeological reconsideration of solar mythology” Karlene Jones-Bley czytamy, że „wspólnymi elementami tych naczyń są promieniste lub gwiaździste motywy w połączeniu z wzorem krzyża, wszystkie znajdujące się na podstawie naczyń…”. W tych samych komorach z Linkardstown zostala znaleziona, prosta okrągłodenna misa barkowa razem ze zdobionymi garnkami.

This is the list of all the Linkardstown cist burials i could find:

Oto lista wszystkich grobów komorowych w Linkardstown, jakie udało mi się znaleźć:

Ballintruer More, Co Wicklow

Clogher Lower (Co. Roscommon)

Ballinagore (Co. Wicklow)

Knockast, Co. Westmeath

Baunogenasraid, Co. Kilkenny

Knockmaree, Co. Dublin

Drimnagh, Co. Dublin

They are mostly found in Eastern and Central part of Ireland.

2. Cists narrow towards the top and are covered by a massive capstone or stones.

3. Cists were cobbled, had a floor made of stone and sand.

4. Cists were sealed. Space between the stones in filled with smaller stones (Linkardstown Cists) and clay (Montenegrian tumuluses)

5. Each cist contained single burial

6. Central stone dolmen cist was covered by multilayered tumulus with multiple stone curbs

7. Funerary offerings contained decorated and undecorated food ware.1. Centralne kamienne komory dolmenowe poligonalne (kopce Linkardstown) lub prostokątne (kopce czarnogórskie), które zostały zbudowane na powierzchni ziemi. 2. Kopce zwężają się ku górze i są przykryte masywnym kamieniem szczytowym lub kamieniami.

3. Kopce były brukowane, miały podłogę z kamienia i piasku.

4. Kopce były uszczelnione. Przestrzeń między kamieniami była wypełniona mniejszymi kamieniami (kopce Linkardstown) i gliną (kopce czarnogórskie)

5. Każdy kopiec zawierał pojedynczy pochówek

6. Centralna kamienna komora dolmenowa była przykryta wielowarstwowym kopcem z wieloma kamiennymi krawężnikami

7. Ofiary pogrzebowe zawierały zdobione i nieozdobione naczynia gospodarskie.

Why no one made any link between the Linkardstown Cist burials and Montenegrian tumuluses before now?

Dlaczego nikt wcześniej nie powiązał pochówków komorowych w Linkardstown z kopcami czarnogórskimi?

Well firstly, as I said in my posts about Montenegrian tumuluses, they were discovered very recently and there is very little published data about them outside Montenegro. Secondly the Montenegrian tumuluses were originally dated to 2nd millennium BC and the Linkardstown Cist burials were originally dated to 4th millennium BC. So this is very big time difference and any similarity across such time frame is ususally attributed to chance.

Cóż, po pierwsze, jak wspomniałem w moich postach o kopcach czarnogórskich, zostały one odkryte bardzo niedawno i jest bardzo mało opublikowanych danych na ich temat poza Czarnogórą. Po drugie, kopce czarnogórskie były pierwotnie datowane na 2. tysiąclecie p.n.e., a groby w Linkardstown były pierwotnie datowane na 4. tysiąclecie p.n.e. Jest to więc bardzo duża różnica czasowa i wszelkie podobieństwa w takich ramach czasowych są zwykle przypisywane przypadkowi.

But recently both Linkardstown Cist burials and Montenegrian tumuluses did some serious time travel which brought them much much closer together on a timeline. Montenegrian tumuluses were dated to the period between 3000 BC and 2400 BC. The Linkardstown Cist burials were recently dated and the results were published in the article entitled „Radiocarbon Dates for Neolithic Single Burials” published by A. L. Brindley and J. N. Lanting. The C14 dates fall to the period between 4800 – 4200 BP. BP means „before present” but really it means „before 1950”. Why 1950? Because the „present” time changes, standard practice is to use 1 January 1950 as commencement date of the age scale, reflecting the fact that radiocarbon dating became practicable in the 1950s. The abbreviation „BP”, with the same meaning, has also been interpreted as „Before Physics”; that is, before nuclear weapons testing artificially altered the proportion of the carbon isotopes in the atmosphere, making dating after that time likely to be unreliable. And the reason why additional radioactivity produced by humans affects radiocarbon dating so much is because radiocarbon dating is based on measuring of the amount of radioactive carbon (C14, radiocarbon) in organic matter.

Ale ostatnio zarówno groby w Linkardstown, jak i kopce czarnogórskie odbyły poważną podróż w czasie, która znacznie je do siebie zbliżyła na osi czasu. Kopce czarnogórskie były datowane na okres między 3000 p.n.e. a 2400 p.n.e. Groby w Linkardstown zostały niedawno datowane, a wyniki zostały opublikowane w artykule zatytułowanym „Radiocarbon Dates for Neolithic Single Burials” opublikowanym przez A. L. Brindleya i J. N. Lantinga. Daty C14 przypadają na okres 4800–4200 lat p.n.e. BP oznacza „przed teraźniejszością”, ale tak naprawdę oznacza „przed 1950 rokiem”. Dlaczego 1950? Ponieważ czas „teraźniejszość” ulega zmianie, standardową praktyką jest używanie 1 stycznia 1950 roku jako daty rozpoczęcia skali wieku, co odzwierciedla fakt, że datowanie radiowęglowe stało się praktyczne w latach 50. Skrót „BP” o tym samym znaczeniu był również interpretowany jako „Przed fizyką”; to znaczy przed testami broni jądrowej, które sztucznie zmieniły proporcje izotopów węgla w atmosferze, co sprawiało, że datowanie po tym czasie prawdopodobnie było niepewne. A powodem, dla którego dodatkowa radioaktywność wytwarzana przez ludzi tak bardzo wpływa na datowanie radiowęglowe, jest to, że datowanie radiowęglowe opiera się na pomiarze ilości radioaktywnego węgla (C14, radiowęgiel) w materii organicznej.

The radiocarbon dating method is based on the fact that radiocarbon (C14) is constantly being created in the atmosphere by the interaction of cosmic rays with atmospheric nitrogen. The resulting radiocarbon combines with atmospheric oxygen to form radioactive carbon dioxide, which is incorporated into plants by photosynthesis; animals then acquire C14 by eating the plants. When the animal or plant dies, it stops exchanging carbon with its environment, and from that point onwards the amount of C14 it contains begins to decrease as the C14 undergoes radioactive decay and gets converted into a stable C12 carbon isotope. Measuring the amount of C14 relative to C12 in a sample from a dead plant or animal such as piece of wood or a fragment of bone provides information that can be used to calculate when the animal or plant died. The older a sample is, the less C14 there is to be detected.

Metoda datowania radiowęglowego opiera się na fakcie, że radiowęgiel (C14) jest stale wytwarzany w atmosferze przez interakcję promieni kosmicznych z atmosferycznym azotem. Powstały radiowęgiel łączy się z atmosferycznym tlenem, tworząc radioaktywny dwutlenek węgla, który jest włączany do roślin przez fotosyntezę; zwierzęta następnie pozyskują C14, zjadając rośliny. Kiedy zwierzę lub roślina umiera, przestaje wymieniać węgiel ze swoim otoczeniem, a od tego momentu ilość zawartego w nim C14 zaczyna się zmniejszać, ponieważ C14 ulega rozpadowi radioaktywnemu i zostaje przekształcony w stabilny izotop węgla C12. Pomiar ilości C14 w stosunku do C12 w próbce z martwej rośliny lub zwierzęcia, takiej jak kawałek drewna lub fragment kości, dostarcza informacji, których można użyć do obliczenia, kiedy zwierzę lub roślina umarło. Im starsza próbka, tym mniej C14 można wykryć.

Originally it was thought that the amount of C14 absorbed by plants every year was the same resulting in the constant C14/C12 ratio. But people soon started to wonder if this was really the case or was it possible that the amount of C14 in the atmosphere varied through time.

Początkowo uważano, że ilość C14 wchłaniana przez rośliny każdego roku jest taka sama, co skutkuje stałym stosunkiem C14/C12.Jednak ludzie wkrótce zaczęli się zastanawiać, czy tak jest naprawdę, czy też możliwe jest, że ilość C14 w atmosferze zmieniała się w czasie.

Over time, discrepancies began to appear between the known chronology for the oldest Egyptian dynasties and the radiocarbon dates of Egyptian artefacts. Neither the pre-existing Egyptian chronology nor the new radiocarbon dating method could be assumed to be accurate, but a third possibility was that the C14/C12 ratio had changed over time. The question was resolved by the study of tree rings: comparison of overlapping series of tree rings allowed the construction of a continuous sequence of tree-ring data that spanned 13,900 years. In the 1960s, Hans Suess was able to use the tree-ring sequence to show that the dates derived from radiocarbon were consistent with the dates assigned by Egyptologists. This was possible because although annual plants, such as corn, have a C14/C12 ratio that reflects the atmospheric ratio at the time they were growing, trees only add material to their outermost tree ring in any given year, while the inner tree rings don’t get their C14 replenished and instead start losing C14 through decay. Hence each ring preserves a record of the atmospheric C14/C12 ratio of the year it grew in. Carbon-dating the wood from the tree rings themselves provides the check needed on the atmospheric C14/C12 ratio. Carbon-dating of the tree rings made it possible to construct curves designed to correct the errors caused by the variation over time in the C14/C12 ratio. This correction process is called radiocarbon date calibration.

Z czasem zaczęły pojawiać się rozbieżności między znaną chronologią najstarszych egipskich dynastii a datowaniami radiowęglowymi egipskich artefaktów. Ani istniejącej wcześniej egipskiej chronologii, ani nowej metody datowania radiowęglowego nie można było uznać za dokładne, ale trzecią możliwością było to, że stosunek C14/C12 zmienił się w czasie. Kwestia została rozwiązana przez badanie słojów drzew: porównanie nakładających się serii słojów drzew pozwoliło na skonstruowanie ciągłej sekwencji danych dotyczących słojów drzew, która obejmowała 13 900 lat. W latach 60. Hans Suess był w stanie wykorzystać sekwencję słojów drzew, aby wykazać, że daty uzyskane z radiowęgla były zgodne z datami przypisanymi przez egiptologów. Było to możliwe, ponieważ chociaż rośliny jednoroczne, takie jak kukurydza, mają stosunek C14/C12, który odzwierciedla stosunek atmosferyczny w czasie, gdy rosły, drzewa dodają materiał tylko do swojego najbardziej zewnętrznego słoja drzewnego w danym roku, podczas gdy wewnętrzne słoje drzewne nie otrzymują swojego C14 i zamiast tego zaczynają tracić C14 poprzez rozkład. Stąd każdy pierścień zachowuje zapis atmosferycznego stosunku C14/C12 z roku, w którym powstał. Datowanie węglem drewna z samych słojów drzew zapewnia potrzebną kontrolę atmosferycznego stosunku C14/C12. Datowanie węglem słojów drzew umożliwiło skonstruowanie krzywych zaprojektowanych w celu skorygowania błędów spowodowanych przez zmiany w czasie stosunku C14/C12. Ten proces korekcji nazywa się kalibracją datowania radiowęglowego.

So… Now that we know how the radiocarbon dating works, let’s get back to the Linkardstown Cist burials. The radiocarbon dates obtained from the bones deposed in these burials fall into the period 4800 – 4200 BP. If we assume that the C14/C12 ratio was constant during last 5000 years, then these two dates translate into 2800 – 2200 BC. But if we take into account the variability of the C14/C12 ratio and use the calibration curve to correct the variation error, we end up with calibrated dates 3400 – 2800 BC.

Więc… Teraz, gdy wiemy, jak działa datowanie radiowęglowe, wróćmy do pochówków komorowych w Linkardstown. Datowanie radiowęglowe uzyskane z kości złożonych w tych pochówkach przypada na okres 4800 – 4200 lat p.n.e. Jeśli założymy, że stosunek C14/C12 był stały przez ostatnie 5000 lat, to te dwie daty przekładają się na 2800 – 2200 p.n.e. Ale jeśli weźmiemy pod uwagę zmienność stosunku C14/C12 i użyjemy krzywej kalibracji, aby skorygować błąd zmienności, otrzymamy skalibrowane daty 3400–2800 p.n.e.

And this is where things get fuzzy. And the reason is that the radiocarbon date calibration is based on one very big assumption: that the C14/C12 ratio obtained from a tree ring in Germany dated to 3000 BP is the same for instance in Ireland at the same time and across the whole northern hemisphere…And this does not have to be the case. We have basically replaced the assumption that the C14/C12 ratio is constant in time with the assumption that the C14/C12 ratio is constant in space. And what is more, the initial calibration of the radiocarbon date calibration curve was done by comparing the radiocarbon dates with archaeological dates, which were obtained using again assumptive methods which could also be imprecise. Basically the measurement of of the imprecision of the radiocarbon dating was done by a measure which was itself more or less guessed and therefore imprecise…

I tu zaczyna się niejasność. A powodem jest to, że kalibracja datowania radiowęglowego opiera się na jednym bardzo dużym założeniu: że stosunek C14/C12 uzyskany z pierścienia drzewa w Niemczech datowanego na 3000 lat temu jest taki sam na przykład w Irlandii w tym samym czasie i na całej półkuli północnej… I nie musi tak być. Zasadniczo zastąpiliśmy założenie, że stosunek C14/C12 jest stały w czasie, założeniem, że stosunek C14/C12 jest stały w przestrzeni. Co więcej, początkowa kalibracja krzywej kalibracji datowania radiowęglowego została przeprowadzona poprzez porównanie dat radiowęglowych z datami archeologicznymi, które uzyskano przy użyciu ponownie domniemanych metod, które również mogą być niedokładne. Zasadniczo pomiar niedokładności datowania radiowęglowego został wykonany za pomocą pomiaru, który sam w sobie był mniej lub bardziej zgadywany, a zatem niedokładny…

This is actually recognized problem. We have to correct the measured date using calibration, but we know that both the measuring process and the calibration process have huge margin of error. And this is why we often see things like: „this object was dated to the period 3500 – 3200 BC…”

To jest faktycznie rozpoznany problem. Musimy skorygować zmierzoną datę za pomocą kalibracji, ale wiemy, że zarówno proces pomiaru, jak i proces kalibracji mają ogromny margines błędu. I dlatego często widzimy takie rzeczy jak: „ten obiekt został datowany na okres 3500 – 3200 p.n.e.”

So….Where were we? Ah, the Linkardstown Cist burials and their relationship with the Montenegrian tumuluses. If we use calibrated dates then the Linkardstown Cist burials directly predate the Montenegrian tumuluses. But if we use plain dates then the Linkardstown Cist burials completely overlap with the Montenegrian tumuluses. I believe that the truth is somewhere in the middle. I believe that the Linkardstown Cist burials are probably slightly later than the calibrated dates and that they partially overlap with the Montenegrian tumuluses. But even if we stick with the calibrated dates of the Linkardstown Cist burials, we still have a very interesting situation indeed. We have two almost identical burial structures being built first in Ireland and then in Montenegro either during immediate succeeding periods or during partially overlapping periods.

Więc… Gdzie byliśmy? Ach, groby komorowe w Linkardstown i ich związek z kurhanami czarnogórskimi.Jeśli użyjemy skalibrowanych dat, to Groby w Linkardstown bezpośrednio poprzedzają kopce czarnogórskie.Ale jeśli użyjemy zwykłych dat, groby w Linkardstown Cist całkowicie pokrywają się z kopcami czarnogórskimi.Wierzę, że prawda leży gdzieś pośrodku.Wierzę, że groby w Linkardstown są prawdopodobnie nieco późniejsze niż daty kalibrowane i że częściowo pokrywają się z kopcami czarnogórskimi.Ale nawet jeśli będziemy trzymać się skalibrowanych dat grobów w Linkardstown, nadal mamy do czynienia z bardzo interesującą sytuacją.Mamy dwie niemal identyczne struktury grobowe budowane najpierw w Irlandii, a następnie w Czarnogórze, albo w okresach bezpośrednio następujących po sobie, albo w okresach częściowo nakładających się.

Now we could say that that was a coincidence and that Ireland and Montenegro are too far apart geographically to have been able to influence each other culturally in the 3rd millennium BC. Well we could say that, if it wasn’t for the fact that we know that there was a migration from Montenegro via Sicily and Iberia to Ireland during the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. A migration which brought metallurgy, oxen, cist burials, golden cross discs and today’s Irish male population main Y haplogroup R1b genes. Irish Annals preserved the record of this migration under Partholon, and now we have archaeological and genetic data to prove that these records are true histories.

Teraz moglibyśmy powiedzieć, że to był zbieg okoliczności i że Irlandia i Czarnogóra są zbyt oddalone geograficznie, aby mogły na siebie wpływać kulturowo w III tysiącleciu p.n.e. Cóż, moglibyśmy tak powiedzieć, gdyby nie fakt, że wiemy, że miała miejsce migracja z Czarnogóry przez Sycylię i Iberię do Irlandii w pierwszej połowie III tysiąclecia p.n.e. Migracja, która przyniosła metalurgię, woły, groby w skrzyniach, złote krzyże i dzisiejsze męskie geny głównej haplogrupy Y R1b populacji irlandzkiej. Irlandzkie Roczniki zachowały zapis tej migracji pod przywództwem Partholona, a teraz mamy dane archeologiczne i genetyczne, które dowodzą, że te zapisy są prawdziwymi historiami.

But was this cultural influence bidirectional?

Ale czy ten wpływ kulturowy był dwukierunkowy?

The Linkardstown Cist burials were built in Ireland just before and during the initial phase of the „raising” of the cists from the ground in Montenegrian tumuluses. Is it possible that who ever built Linkardstown Cist burials in Ireland at the end of the 4th millennium and the beginning of the 3rd millennium somehow ended up in Montenegro at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, bringing with them the tradition of burying their dead in Linkardstown Cist burials? And is it possible that they, after mixing with Yamna people, influenced the process of „raising” of the stone cists in Montenegrian tumuluses above ground, eventually producing rectangular copies of the Linkardstown Cist burials?

Groby w komorach w Linkardstown zostały zbudowane w Irlandii tuż przed i w początkowej fazie „podnoszenia” komór grobowych z ziemi w kopcach czarnogórskich. Czy możliwe jest, że ktokolwiek zbudował groby w Linkardstown w Irlandii pod koniec IV tysiąclecia i na początku III tysiąclecia, jakoś trafił do Czarnogóry na początku III tysiąclecia p.n.e., przywożąc ze sobą tradycję grzebania zmarłych w grobach w Linkardstown? I czy możliwe jest, że oni, po zmieszaniu się z ludem Jamna, wpłynęli na proces „podnoszenia” kamiennych kopców w czarnogórskich tumulusach ponad ziemię, ostatecznie tworząc prostokątne kopie grobów w Linkardstown?

Well it is possible actually. The builders of the Linkardstown Cist burials could have arrived from Ireland to Montenegro following the maritime trading route along the Eastern Atlantic and Northern Mediterranean coast. The same route that Partholon followed during his migration from Montenegro to Ireland 500 years later.

Cóż, jest to w zasadzie możliwe. Budowniczowie grobów w Linkardstown mogli przybyć z Irlandii do Czarnogóry, podążając morskim szlakiem handlowym wzdłuż wschodniego Atlantyku i północnego wybrzeża Morza Śródziemnego. Tą samą trasą, którą podążał Partholon podczas swojej migracji z Czarnogóry do Irlandii 500 lat później.

Interesting, very interesting. What do you think of all this?

Interesujące, bardzo interesujące. Co o tym wszystkim myślisz?

Anyway, while you are pondering this, here is some data on so far excavated Linkardstown Cist burials. I hope you will find it interesting. Also if you have any additional data about Linkardstown Cist burials or any similar burials from that period pleas let me know.

Tak czy inaczej, podczas gdy rozważasz to, oto kilka danych na temat dotychczas wykopanych grobów w Linkardstown. Mam nadzieję, że uznasz je za interesujące. Jeśli masz dodatkowe dane na temat grobów w Linkardstown Cist lub podobnych grobów z tego okresu, daj mi znać.

Ardcroney Linkardstown Cist burial (from Modern Antiquarian)

A massive central cist of sub-megalithic proportions was uncovered at the centre of a denuded cairn which originally measured about 33mn. in diameter of which about 20m. remains. About 2.5in. of the cairn height survives, The cist was polygonal in plan and consisted of a single large stone inclining at about 60 degrees at each side and of two vertical boulders at each end. The floor was paved with small irregularly-shaped flat stones and measured 1.75in. by 1.4in. The cist was 69cm. high (internally) and 1.48m. by 93cm. at the mouth. It was covered by a large single capstone, 1.9m. long by 1.73m. wide by 51cm. in max. thickness.

Ardcroney Linkardstown Cist burial (z Modern Antiquarian)

Ogromna centralna komora o submegalitycznych proporcjach została odkryta w centrum odsłoniętego kopca, który pierwotnie miał około 33 m średnicy, z czego pozostało około 20 m. Zachowało się około 2,5 cala wysokości kopca. Komora miała wielokątny plan i składała się z pojedynczego dużego kamienia nachylonego pod kątem około 60 stopni z każdej strony i dwóch pionowych głazów na każdym końcu. Podłoga była wyłożona małymi, nieregularnie ukształtowanymi płaskimi kamieniami o wymiarach 1,75 cala na 1,4 cala. Komora miała 69 cm. wysokości (wewnętrznie) i 1,48 m. na 93 cm. przy ujściu. Była przykryta dużym pojedynczym kamieniem szczytowym o długości 1,9 m. na 1,73 m. szerokości i maksymalnej grubości 51 cm.

Two disarticulated and unburnt skeletons identified by Prof. CA. Erskine as being of men of 17 and 45 years – lay on tile paved floor, one on either side of a shouldered, round-bottomed, highly decorated shallow bowl of late Neolithic date, the bones had been disturbed before investigation. The bowl was covered with channelled decoration comprised of pendant triangles of horizontal lines and dots as well as circumferential lines around the rim and shoulder, the ornament on the base being arranged on a quadripartite system.

Dwa rozczłonkowane i niespalone szkielety zidentyfikowane przez prof. CA. Erskine’a jako szkielety mężczyzn w wieku 17 i 45 lat – leżały na wyłożonej płytkami podłodze, jeden po każdej stronie płytkiej misy z ramionami i okrągłym dnem, bogato zdobionej z późnego neolitu, kości zostały naruszone przed badaniem. Misa była pokryta żłobkowaną dekoracją składającą się z wiszących trójkątów poziomych linii i kropek, a także linii obwodowych wokół krawędzi i ramienia, ornament na podstawie był ułożony w układzie czworokątnym.

The cist and cairn fit into the Linkardstown group while the bowl and mode of burial make this the most western example, so far, of the ‘South Leinster” Single Burial tradition of the late Neolithic. A full excavation of the structure will explore the nature of the cairn, the existence of kerbs, and the relationship of cairn, and a now removed earthen ring, to the cist.

Komora i kopiec pasują do grupy Linkardstown, podczas gdy misa i sposób pochówku sprawiają, że jest to najbardziej zachodni przykład, jak dotąd, tradycji pojedynczego pochówku „South Leinster” z późnego neolitu. Pełne wykopaliska konstrukcji pozwolą zbadać naturę kopca, istnienie krawężników oraz związek kopca i obecnie usuniętego pierścienia ziemnego z komorą.

You can find more pictures of the Adcroney site on this page on the Modern Antiquarian website.

Więcej zdjęć stanowiska Adcroney można znaleźć na tej stronie witryny Modern Antiquarian.

Ashleypark Linkardstown Cist burial (from Modern Antiquarian)

Situated on the NW shoulder of an E-W ridge in farmland. A megalithic structure is exposed in a round mound which in turn is encircled by two low wide banks with internal ditches giving an overall diameter of 90m. The structure was uncovered during bulldozing operations in 1980 after which the site was excavated (Manning, 1985a). The mound, 26m in diameter, consists of a cairn core, 18 to 20m in diameter, overlain by a covering of clay, The megalithic structure stands eccentrically within the cairn. It is trapezoidal in plan, some 5m long and narrows from 2.3m wide at the SE or inner end to 1.3m at the open NW end. It was built around a limestone erratic which has a sloping upper surface and serves as a floorstone. Two stones form the inner end of the structure. There is a stone at right angles to the SW side of the structure 1.2m from the inner end. This, in combination with a rough wall divides it in two. That part of it forward of the dividing wall was filled with cairn stones among which animal bones and the bones of a child less than a year old were found. The inner end of the structure, roofed by a skeletal remains of an adult male and a child were found here along with a variety of animal bones, a bone point, some chert flakes and Neolithic pottery, including sherds bearing channelled decoration.

Położony na północno-zachodnim ramieniu grzbietu E-W na terenach rolniczych. Megalityczna struktura jest odsłonięta w okrągłym kopcu, który z kolei jest otoczony dwoma niskimi, szerokimi wałami z wewnętrznymi rowami o całkowitej średnicy 90 m. Konstrukcja została odkryta podczas prac spychających w 1980 r., po czym stanowisko zostało wykopane (Manning, 1985a). Kopiec o średnicy 26 m składa się z rdzenia kopca o średnicy 18–20 m, na którym znajduje się pokrycie z gliny, Megalityczna struktura stoi ekscentrycznie wewnątrz kopca. Ma trapezoidalny plan, około 5 m długości i zwęża się od 2,3 m szerokości na południowo-wschodnim lub wewnętrznym końcu do 1,3 m na otwartym północno-zachodnim końcu. Została zbudowana wokół wapiennego głazu narzutowego, który ma pochyłą górną powierzchnię i służy jako kamień podłogowy. Dwa kamienie tworzą wewnętrzny koniec struktury. Jest kamień pod kątem prostym do południowo-zachodniej strony struktury, 1,2 m od wewnętrznego końca. To, w połączeniu z chropowatą ścianą, dzieli ją na dwie części. Ta część przed ścianą działową była wypełniona kamieniami kopca, wśród których znaleziono kości zwierząt i kości dziecka w wieku poniżej roku. Wewnętrzny koniec struktury, zadaszony szczątkami szkieletu dorosłego mężczyzny i dziecka, został tutaj znaleziony wraz z różnymi kośćmi zwierząt, ostrzem kości, kilkoma odłamkami krzemienia i neolityczną ceramiką, w tym skorupami z dekoracją kanałową.

You can find more pictures of the site on this page on the Modern Antiquarian website and on this page from Secret Ireland.

Więcej zdjęć stanowiska można znaleźć na tej stronie witryny Modern Antiquarian oraz na tej stronie Secret Ireland.

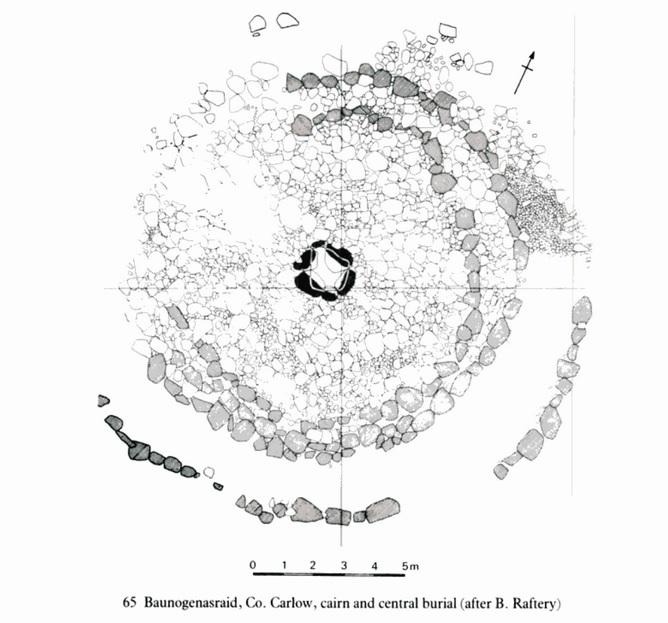

Baunogenasraid Linkardstown cist burial (From Irish Stones)

Baunogenasraid Linkardstown cist burial (From Irish Stones)

The burial was discovered in the Autumn 1972 during the excavations of a tumulus. The first stage of the excavation led to the discovery of ten human burials, five cremations and five inhumations, along with a single flint flake and a food vessel that helped archaeologists dating the remains to the Early Bronze Age.

The second stage of the excavation discovered a cist placed at the centre of a large cairn. Inside the cist the disarticulated, unburnt remains of a male adult described „of exceptional size” were found along with a finely decorated bowl of Linkardstown type, that is a bowl with a T-rim around, and a small perforated object of lignite.

Pochówek został odkryty jesienią 1972 roku podczas wykopalisk kopca. Pierwszy etap wykopalisk doprowadził do odkrycia dziesięciu ludzkich pochówków, pięciu kremacji i pięciu inhumacji, a także pojedynczego odłupka krzemienia i naczynia na żywność, co pomogło archeologom w datowaniu szczątków na wczesną epokę brązu. Drugi etap wykopalisk odkrył cysternę umieszczoną w centrum dużego kopca. Wewnątrz cysterny znaleziono rozczłonkowane, niespalone szczątki dorosłego mężczyzny opisanego jako „wyjątkowej wielkości” wraz z pięknie zdobioną misą typu Linkardstown, czyli misą z krawędzią w kształcie litery T, oraz małym perforowanym przedmiotem z lignitu.

You can find more pictures of this site on this page of the Irish Stones site.

Więcej zdjęć stanowiska można znaleźć na tej stronie witryny Irish Stones.

Knockmaree Linkardstown cist burial (From fountain resource group)

Pochówek w komorze w Knockmaree Linkardstown (z Fountain Resource Group)

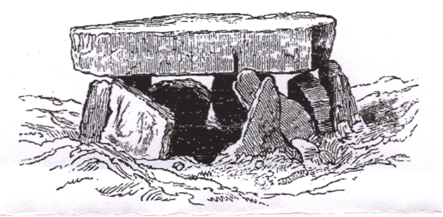

The stones we see today at Knockmaree are what are left of the original tomb, the earthen mound long since gone.

Kamienie, które widzimy dzisiaj w Knockmaree, to pozostałości oryginalnego grobowca, ziemnego kopca, który dawno zniknął.

The site at Knockmaree was first discovered in 1838, during landscaping works. It was brought to the attention of the Royal Irish Academy (RIA; the academy for the sciences and humanities, including antiquaries), by a Mr. T. Drummond . When members of the RIA first visited the site, it looked distinctly different from today. They saw a large mound, surrounded by a few smaller ones. Upon excavating the mound and examining its contents, they found the tomb itself and a number of pottery vessels. The description below is the original description of the tomb, by George Petrie: “The tomb consisted of a table, or covering stone, 6feet 6inches in length, from 3 feet 6 inches to 3 feet in breadth and 14 inches in thickness. This stone rested on five supporting stones, varying from 2 feet 6 inches to 1 foot 3 inches in breadth and about 2 feet in height…and there were 5 other stones, not used for supports, but as forming the enclosure of the tomb…”

Miejsce w Knockmaree zostało odkryte po raz pierwszy w 1838 roku podczas prac krajobrazowych. Zostało ono przedstawione Royal Irish Academy (RIA; akademia nauk ścisłych i humanistycznych, w tym antykwariuszy) przez pana T. Drummonda. Kiedy członkowie RIA po raz pierwszy odwiedzili to miejsce, wyglądało ono wyraźnie inaczej niż dzisiaj. Zobaczyli duży kopiec otoczony kilkoma mniejszymi. Po wykopaniu kopca i zbadaniu jego zawartości znaleźli sam grobowiec i kilka naczyń ceramicznych. Poniższy opis to oryginalny opis grobowca autorstwa George’a Petrie: „Grobowiec składał się ze stołu lub kamienia przykrywającego o długości 6 stóp i 6 cali, szerokości od 3 stóp i 6 cali do 3 stóp i grubości 14 cali. Kamień ten spoczywał na pięciu kamieniach podporowych, o szerokości od 2 stóp i 6 cali do 1 stopy i 3 cali i wysokości około 2 stóp… i było 5 innych kamieni, nie używanych jako podpory, ale jako obudowa grobowca…”

What is interesting is that the pottery vessels mentioned above were identified as funerary urns from the Bronze Age period and date to approximately 2500 BC. You can see why I am not sure that the calibrated dating of the Linkardstown Cist burials is correct.

Ciekawostką jest to, że wspomniane powyżej naczynia ceramiczne zostały zidentyfikowane jako urny pogrzebowe z epoki brązu i datowane na około 2500 r. p.n.e. Widzisz, dlaczego nie jestem pewien, czy skalibrowane datowanie pochówków w Linkardstown jest prawidłowe.

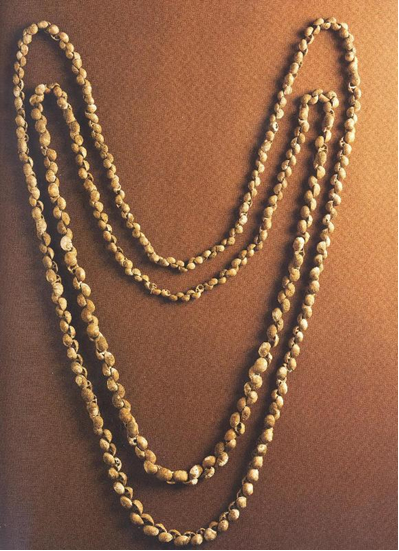

Two adult male skeletons, the skeleton of a dog and a large number of seashells, were all recovered from within the tomb. The shells were all local, from the Dublin coastline, and formed two necklaces, one of which can be seen on the next picture. It was found within the tomb, under the skulls of the male skeletons. From Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland Irish Antiquities, 2002, page 73.

Dwa dorosłe szkielety mężczyzn, szkielet psa i duża liczba muszli morskich, zostały wydobyte z grobowca. Muszle były lokalne, z wybrzeża Dublina i tworzyły dwa naszyjniki, z których jeden można zobaczyć na następnym zdjęciu. Został znaleziony w grobowcu, pod czaszkami szkieletów mężczyzn. Z Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland Irish Antiquities, 2002, strona 73.

This is the original drawing of the tomb from the Royal Irish Academy’s Report. From Petrie, 1838. Page 188.

To jest oryginalny rysunek grobowca z raportu Royal Irish Academy. Z Petrie, 1838. Strona 188.

You can find more pictures of this site on this page of the Irish Stones site and this page of the Fountain resource group.

Więcej zdjęć tego miejsca można znaleźć na tej stronie witryny Irish Stones i tej stronie grupy zasobów Fountain.

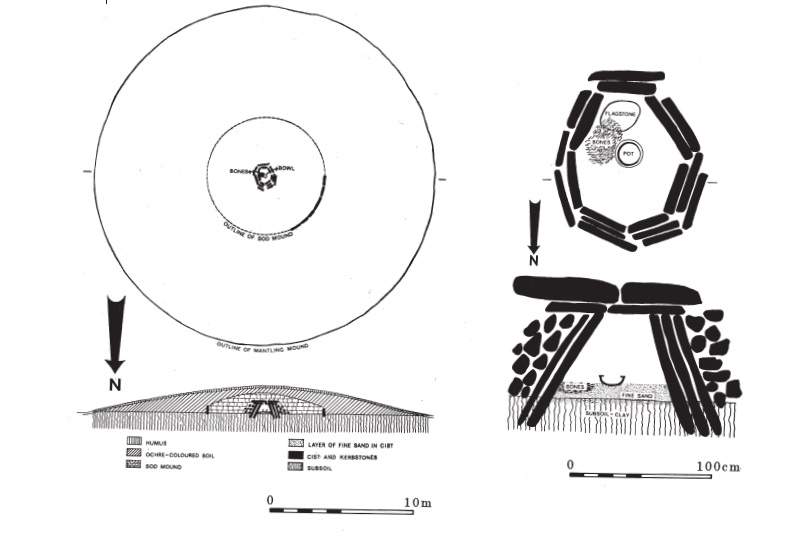

Ballintruer More Linkardstown cist burial (from A Neolithic Burial Mound at Ballintruer More, Co. Wicklow)

Pochówek w kopcu Ballintruer More Linkardstown (z kopca grobowego Neolithic Burial Mound at Ballintruer More, Co. Wicklow)

The destruction by bulldozer of a circular mound with kerb revealed a polygonal cist with a floor of fine sand and which contained some disarticulated and apparently broken bones representing part of the skeleton of an adult male. An empty pottery vessel had been placed in the centre of the grave immediately to the west of the bones.

Zniszczenie przez buldożer okrągłego kopca z krawężnikiem ujawniło wielokątny pojemnik z dnem z drobnego piasku, który zawierał kilka rozczłonkowanych i najwyraźniej złamanych kości, reprezentujących część szkieletu dorosłego mężczyzny. Puste naczynie ceramiczne zostało umieszczone w centrum grobu bezpośrednio na zachód od kości.

This pot, like a number of vessels from other burials of this type, is a fine Bipartite Bowl. The cist was in the middle of a circular mound 24m in diameter and slightly less than 2m high in the middle above the level of the surrounding land. The cist had seven sides. Each of the side stones had at least one further stone outside it and in three cases there were two additonal supporting stones. All sloped inwards at a steep angle from the bottom to the top, making the bottom at 80cm being much wider than the top at 30cm. The slabs forming the sides were regular, as if specifically selected and shaped for this purpose and varied in thickness from 2 to 8 cm. They averaged 95 cm in length and of this 30 cm was inserted into sub soil, which was a buff coloured clay. The stone cist was packed on all sides with with stones averaging 20cm in width. Finally, it was closed by two thing lower capstones over which lay two much heavier ones. The cist with its external stone packing was covered by a circular mound now of gray clay, held in position by a kerb of large stones. You can find more details on this cist tumulus in these two articles:

To naczynie, podobnie jak wiele naczyń z innych pochówków tego typu, jest piękną misą dwudzielną. Kopalnia znajdowała się pośrodku okrągłego kopca o średnicy 24 m i wysokości nieco mniejszej niż 2 m w środku nad poziomem otaczającego terenu. Kopalnia miała siedem boków. Każdy z bocznych kamieni miał co najmniej jeden dodatkowy kamień na zewnątrz, a w trzech przypadkach były dwa dodatkowe kamienie podporowe. Wszystkie były nachylone do wewnątrz pod ostrym kątem od dołu do góry, przez co dół na wysokości 80 cm był znacznie szerszy niż góra na wysokości 30 cm. Płyty tworzące boki były regularne, jakby specjalnie wybrane i ukształtowane w tym celu i miały różną grubość od 2 do 8 cm. Średnio ok. 95 cm długości i z tego 30 cm zostało włożone do podłoża, które było gliną w kolorze buff. Kamienna komora była wypełniona ze wszystkich stron kamieniami o średniej szerokości 20 cm. Na koniec została zamknięta dwoma niższymi kamieniami szczytowymi, na których leżały dwa znacznie cięższe. Cysta z jej zewnętrznym wypełnieniem kamiennym została przykryta okrągłym kopcem, teraz z szarej gliny, utrzymywanym w pozycji przez krawężnik z dużych kamieni.

You can find more information about this burial in:

Więcej szczegółów na temat tego kopca komorowego można znaleźć w tych dwóch artykułach:

„A Neolithic Burial Mound at Ballintruer More, Co. Wicklow” by Joseph Raftery

Jerpoint west Linkardstown cist burial (from The Excavation of a Neolithic Burial Mound at Jerpoint West, Co. Kilkenny)

This site, which was not marked on the 0.S. maps of the area, was discovered in 1972 when the landowner decided to tip the mound into a adjacent quarry in order to minimise the danger to his livestock. A mechanical excavator was employed for this purpose and roughly two thirds of the area of the site was severely damaged when a large polygonal cist was uncovered. The cist was polygonal in form the sidestones being doubled in some cases. Three, (perhaps four), capstones covered the burial. he floor of the cist was roughly cobbled. It contained a burned and an unburned burial, fragments of plain and decorated Neolithic vessels and a bone pin.

The cist was bedded into the old ground surface. It was placed approximately centrally in a mound of complex construction. A core of boulders piled against the cist. A deposit of flat fairly regular stones each pitched upwards in the direction of the cist. A mantle of soil mixed with a high proportion of sod, in which, at intervals, occurred thin layers of flat stones carefully laid. The soil mound was delimited by three concentric arcs of fairly regular stone laminae resting on the old ground level, between these occurred a series of radially set stones. The site was disturbed on the north and south by modern field boundaries.

To miejsce, które nie zostało oznaczone na 0.S. mapy tego obszaru, odkryto w 1972 r., gdy właściciel ziemski postanowił przenieść kopiec do sąsiedniego kamieniołomu, aby zminimalizować zagrożenie dla swojego bydła. W tym celu wykorzystano koparkę mechaniczną i około dwie trzecie obszaru stanowiska zostało poważnie uszkodzone, gdy odkryto dużą wielokątną komorę. Komora miała kształt wielokąta, a boczne kamienie były w niektórych przypadkach podwojone. Trzy (być może cztery) kamienie szczytowe pokrywały grób. Podłoga komory była grubo wybrukowana. Zawierała spalony i niespalony grób, fragmenty prostych i zdobionych naczyń neolitycznych oraz szpilkę z kości. Komorę osadzono na starej powierzchni gruntu. Umieszczono ją mniej więcej centralnie w kopcu o złożonej konstrukcji. Rdzeń z głazów ułożony przy komorze. Złoże płaskich, dość regularnych kamieni, z których każdy wznosi się w górę w kierunku komory. Płaszcz gleby zmieszanej z dużą ilością darni, w której w odstępach występowały cienkie warstwy płaskich kamieni ostrożnie ułożonych. Kopiec ziemny ograniczony był trzema koncentrycznymi łukami dość regularnych warstw kamiennych spoczywających na starym poziomie gruntu, pomiędzy którymi znajdowała się seria promieniście ułożonych kamieni. Miejsce zostało naruszone od północy i południa przez współczesne granice pól.

You can find more information about this burial in „The Excavation of a Neolithic Burial Mound at Jerpoint West, Co. Kilkenny” by M. FitzG. Ryan .

I hope you enjoyed this article. Until the next time, keep smiling, stay happy and healthy..