Kopce Mala i Velika Gruda

Mala and Velika Gruda tumuluses

Kopce Mala i Velika Gruda

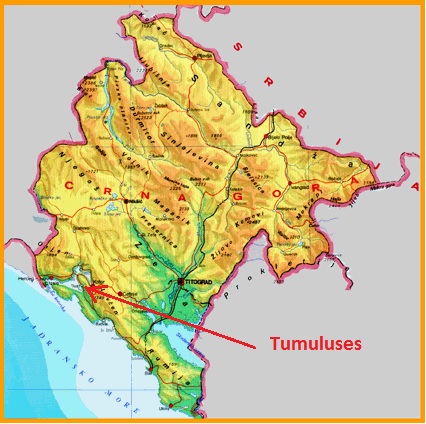

Among many tumuluses, cairns, which are strewn over the hills of Boka Kotorska bay, the two stand out: Velika and Mala Gruda.

Spośród wielu kopców, kurhanów, które są rozsiane na wzgórzach zatoki Boka Kotorska, wyróżniają się dwa: Velika i Mala Gruda.

While the other tumuluses in the area are located on tops of hills, these two tumuluses are located in the middle of the Tivat field. The local people preserved the legends that these two stone tumuluses were Prokletije, piles of stones accumulated through centuries as part of the cursing ceremony. I wrote about Prokletija ceremony in my post entitled „Prokletija – The cursing ceremony„. As a result, these tumuluses were preserved as the taboo linked with Prokletije forbids removal of even a single stone.

Podczas gdy inne kopce w okolicy znajdują się na szczytach wzgórz, te dwa kopce znajdują się pośrodku pola Tivat. Miejscowi ludzie zachowali legendy, że te dwa kamienne kopce to Prokletije, stosy kamieni gromadzone przez stulecia jako część ceremonii przeklinania. O ceremonii Prokletije pisałem w moim poście zatytułowanym „Prokletija – Ceremonia przeklinania”. W rezultacie kopce te zostały zachowane, ponieważ tabu związane z Prokletije zabrania usuwania nawet jednego kamienia.

Velika Gruda and Mala Gruda tumuluses are only 270 meters away from each other. Mala Gruda is a single phase burial tumulus and has only a late Copper Age (early Bronze Age) tumb. Velika Gruda is a multi phase burial which has late Copper age (Early Bronze age), Iron age and Medieval burials. The late Copper Age (early Bronze Age) burial from Velika Gruda is equivalent to the late Copper Age (early Bronze Age) burial from Mala Gruda. These were rich princely graves, full of well made and decorated ceramics and metal objects made from silver, gold and copper alloys. The archaeologists who excavated these burials postulated that the people who were buried inside the Velika and Mala Gruda late Copper Age (early Bronze Age) burials were involved in trades between the Balkan Hinterland and Southern Italy and probably the rest of the Mediterranean.

Kopce Velika Gruda i Mala Gruda są oddalone od siebie o zaledwie 270 metrów. Mala Gruda to jednofazowy kopiec grobowy i ma tylko grobowiec z późnej epoki miedzi (wczesnej epoki brązu). Velika Gruda to wielofazowy pochówek, który obejmuje późną epokę miedzi (wczesną epokę brązu), epokę żelaza i średniowieczne pochówki. Późna epoka miedzi (wczesna epoka brązu) pochówek z Velika Gruda jest odpowiednikiem późnej epoki miedzi (wczesnej epoki brązu) pochówku z Mala Gruda. Były to bogate groby książęce, pełne dobrze wykonanej i zdobionej ceramiki oraz metalowych przedmiotów wykonanych ze srebra, złota i stopów miedzi. Archeolodzy, którzy przeprowadzili wykopaliska w tych grobach, założyli, że ludzie pochowani w grobach z późnej epoki miedzi (wczesnej epoki brązu) w Velika i Mala Gruda brali udział w handlu między Bałkanami i południowymi Włochami, a prawdopodobnie także resztą Morza Śródziemnego.

So who was buried in these tumuluses? The archaeologists admit that despite all the modern procedures, analysis and equipment used it is „difficult to understand who built the Mala and Velika Gruda burials. This is because there is at present so little knowledge about what was going on in the Southwestern Balkans during the time when these tumuluses were built. Basically the problem is that the way these tumuluses were built, the way they were positioned in the low lying landscape as well as some of the burial rite details have no parallels in the Mediterranean basin except in a small area of Montenegro and Northern Albania. The first next similar late Copper Age (early Bronze Age) burial is found in the steppe of the Yamna culture homeland….

Kto więc został pochowany w tych kurhanach? Archeolodzy przyznają, że pomimo wszystkich nowoczesnych procedur, analiz i sprzętu, „trudno zrozumieć, kto zbudował groby Mala i Velika Gruda. Wynika to z faktu, że obecnie istnieje bardzo niewielka wiedza na temat tego, co działo się na południowo-zachodnich Bałkanach w czasie, gdy budowano te kurhany. Zasadniczo problem polega na tym, że sposób, w jaki budowano te kurhany, sposób, w jaki były one pozycjonowane w nisko położonym krajobrazie, a także niektóre szczegóły obrządku pogrzebowego nie mają odpowiedników w basenie Morza Śródziemnego, z wyjątkiem niewielkiego obszaru Czarnogóry i północnej Albanii. Pierwszy kolejny podobny pochówek z późnej epoki miedzi (wczesnej epoki brązu) znajduje się na stepie ojczyzny kultury Jamna….

The investigation of the Velika Gruda tumulus was completed in the early 1990s and the results were published in these two books:

Badania kurhanu Velika Gruda zostały zakończone na początku lat 90. XX wieku, a wyniki opublikowano w następujących dwóch książkach:

„Tumulus burials of the early 3rd millenium BC in the Adriatic – Velika Gruda, Mala Gruda and their context” which was published in 1996 by Margarita Primas who excavated the late Copper Age (early Bronze Age) burial.

„Tumulus burials of the early 3rd millenium BC in the Adriatic – Velika Gruda, Mala Gruda and their context”, która została opublikowana w 1996 przez Margaritę Primas, która przeprowadziła wykopaliska w grobowcu z późnej epoki miedzi (wczesnej epoki brązu).

„The Bronze Age necropolis Velika Gruda (Ops. Kotor, Montenegro) : middle and late Bronze Age groups between Adriatic and Danube” published in 1994 by Philippe. Della Casa who excavated the Middle and Late Bronze Age burials.

„Nekropolia z epoki brązu Velika Gruda (Ops. Kotor, Czarnogóra): grupy z epoki brązu w połowie i na końcu między Adriatykiem a Dunajem” opublikowane w 1994 roku przez Philippe’a Della Casa, który przeprowadził wykopaliska w grobach z epoki brązu w połowie i na końcu.

A short review of both works by John Bintliff was published in the American Journal of Archaeology.

Krótki przegląd obu prac autorstwa Johna Bintliffa został opublikowany w American Journal of Archaeology.

Archaeological investigation of the Mala Gruda tumulus was performed during the period 1970 – 1971. The tumulus was damaged during the First World War, when Austrian army built a bunker on top of it. The tumulus height in the middle is about 4 meters and the diameter is about 20 meters. Originally it was proposed that the tumulus dated to the period 1900 to 1800 BC. Howevere the latest dating pushes the date when this tumulus was built almost 1000 years back into the past to the period between 2800 to 2700 BC.

Badania archeologiczne kopca Mala Gruda przeprowadzono w latach 1970–1971. Kopiec został uszkodzony podczas I wojny światowej, gdy armia austriacka zbudowała na nim bunkier. Wysokość kopca w środku wynosi około 4 metrów, a średnica około 20 metrów. Początkowo zaproponowano, że kopiec datowany jest na okres od 1900 do 1800 p.n.e. Jednak najnowsze datowanie przesuwa datę budowy tego kopca o prawie 1000 lat wstecz na okres między 2800 a 2700 p.n.e.

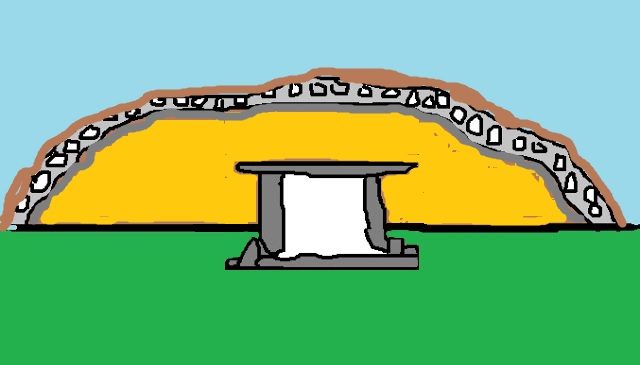

The Mala and Velika Gruda tumuluses have very unusual structure. Remember the Bjelopavlovic tumulus and Mogila na Rake tumulus that I already talked about? They both had central dolmen cists which were built on the surface of the earth. Mala and Velika Gruda tumuluses also have central dolmen cists built from massive stone plates. But these stone plates were placed inside the grave pit which was dug into the earth to the depth of half a meter. First the bottom of the grave pit was covered with a stone plate and then the vertical stone plates were placed on top of it to form the dolmen cist. The cover stone plate was then placed on top of it. The stone dolmen cist was then covered with a tumulus pile of yellow – brown clay. The surface of this clay inner tumulus was then burned using very strong fire, probably during the sacrificial rite which took place on top of this inner tumulus. This resulted in the whole inner clay tumulus being covered with a layer of ash which contained the most of the ceramic and stone finds. The clay inner tumulus was then covered with the layer of stones (large river pebbles) which varied in thickness between 0.3 – 0.5 meters. This stone layer was then covered with earth (humus). It is unclear if his layer of humus was natural or artificial.

Kopce Mala i Velika Gruda mają bardzo nietypową strukturę. Pamiętasz kurhan Bjelopavlovic i kurhan Mogila na Rake, o których już mówiłem? Oba miały centralne dolmeny zbudowane na powierzchni ziemi. Kurhany Mala i Velika Gruda również mają centralne dolmeny zbudowane z masywnych płyt kamiennych. Ale te płyty kamienne umieszczono wewnątrz dołu grobowego, który wykopano w ziemi na głębokość pół metra. Najpierw dno dołu grobowego przykryto płytą kamienną, a następnie na nim umieszczono pionowe płyty kamienne, aby utworzyć kopiec dolmenu. Następnie na nim umieszczono płytę kamienną. Kamienny kopiec dolmenu przykryto kopcem z żółto-brązowej gliny. Powierzchnia tego glinianego wewnętrznego kopca została następnie spalona przy użyciu bardzo silnego ognia, prawdopodobnie podczas rytuału ofiarnego, który odbył się na szczycie tego wewnętrznego kopca. W rezultacie cały wewnętrzny gliniany kopiec został pokryty warstwą popiołu, która zawierała większość znalezisk ceramicznych i kamiennych. Gliniany wewnętrzny kopiec został następnie pokryty warstwą kamieni (dużych otoczaków rzecznych), których grubość wahała się od 0,3 do 0,5 metra. Ta warstwa kamieni została następnie pokryta ziemią (próchnicą). Nie jest jasne, czy ta warstwa próchnicy była naturalna czy sztuczna. Położenie komory dolmenu było północ – południe.

The orientation of the dolmen cist was north – south. The body which was placed inside the dolmen cist was very badly preserved and was not possible to determine its precise position, but it is presumed that it was placed into the cist in the fetal position.

Ciało, które zostało umieszczone w komorze dolmenu, było bardzo źle zachowane i nie można było określić jego dokładnej pozycji, ale przypuszcza się, że zostało umieszczone w komorze w pozycji embrionalnej.

In the north part of the stone cist, next to the scull of the deceased, archaeologists have found five golden lock rings.

W północnej części kamiennej komory, obok czaszki zmarłego, archeolodzy znaleźli pięć złotych pierścieni zabezpieczających.

Lock rings are a type of jewelry from Bronze Age Europe. They are made from gold or bronze and are penannular, providing a slot that is thought to have been used for attaching them as earrings or as hair ornaments. Ireland was a centre of production in the British Isles though rings were made and used across the continent, notably by the Unetice culture of central Europe. But these lock rings from Mala Gruda tumulus predate all the examples from northern Europe by many centuries and millenniums.

Pierścienie zabezpieczające to rodzaj biżuterii z epoki brązu w Europie. Wykonane są ze złota lub brązu i mają kształt półpierścienia, co oznacza szczelinę, która prawdopodobnie służyła do mocowania ich jako kolczyków lub ozdób do włosów. Irlandia była centrum produkcji na Wyspach Brytyjskich, chociaż pierścienie były wytwarzane i używane na całym kontynencie, zwłaszcza przez kulturę unietycką w Europie Środkowej. Jednak te pierścienie zabezpieczające z kurhanu Mala Gruda są starsze od wszystkich okazów z północnej Europy o wiele stuleci i tysiącleci.

The only other lock rings from the late Copper Age (early Bronze Age) period which are similar to the lock rings from Mala gruda tumulus were found in Velika Gruda tumulus and in Gruda Boljevića tumulus, which is even older than the Velika and Mala gruda tumuluses. I will write about the Gruda Boljevića tumulus in my next post. Velika gruda tumulus also had lock rings of the type found in the Lefkas (Leukas) cemetary. But these Lefkas type rings are much simpler than the Mala Gruda type rings, and look like an inferior quality imitation of the Mala Gruda type lock rings. Here are the Lefkas type lock rings from Lefkas cemetary.

Jedyne inne pierścienie zabezpieczające z późnej epoki miedzi (wczesnej epoki brązu), które są podobne do pierścieni zabezpieczających z kurhanu Mala gruda, znaleziono w kurhanie Velika Gruda i w kurhanie Gruda Boljevića, który jest nawet starszy niż kurhany Velika i Mala gruda. O kurhanie Gruda Boljevića napiszę w następnym poście. Kurhan Velika gruda miał również pierścienie zabezpieczające, takie jak te znalezione na cmentarzysku Lefkas (Leukas). Jednak te pierścienie typu Lefkas są o wiele prostsze niż pierścienie typu Mala Gruda i wyglądają jak gorszej jakości imitacja pierścieni zabezpieczających typu Mala Gruda. Oto pierścienie zabezpieczające typu Lefkas z cmentarzyska Lefkas.

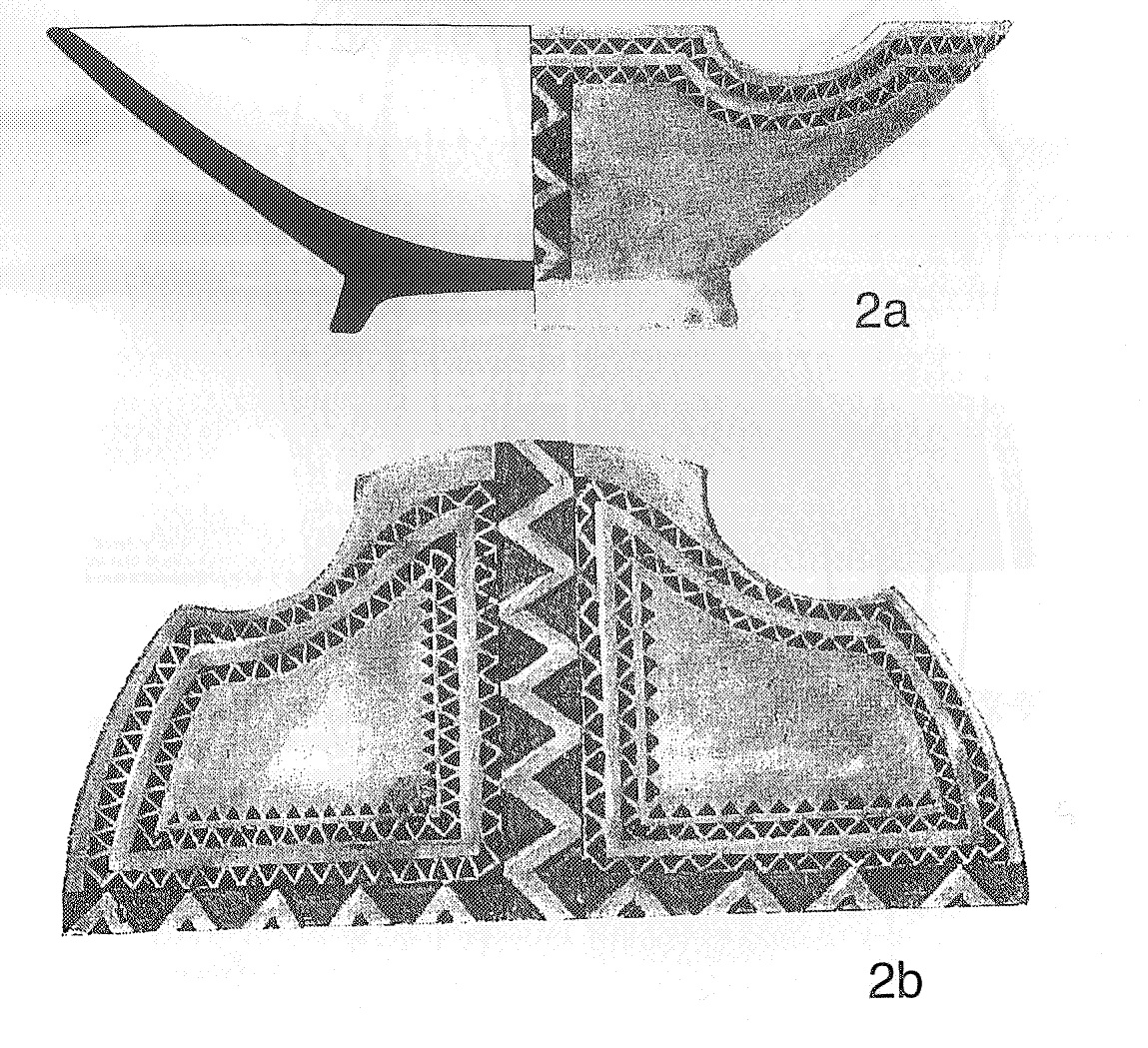

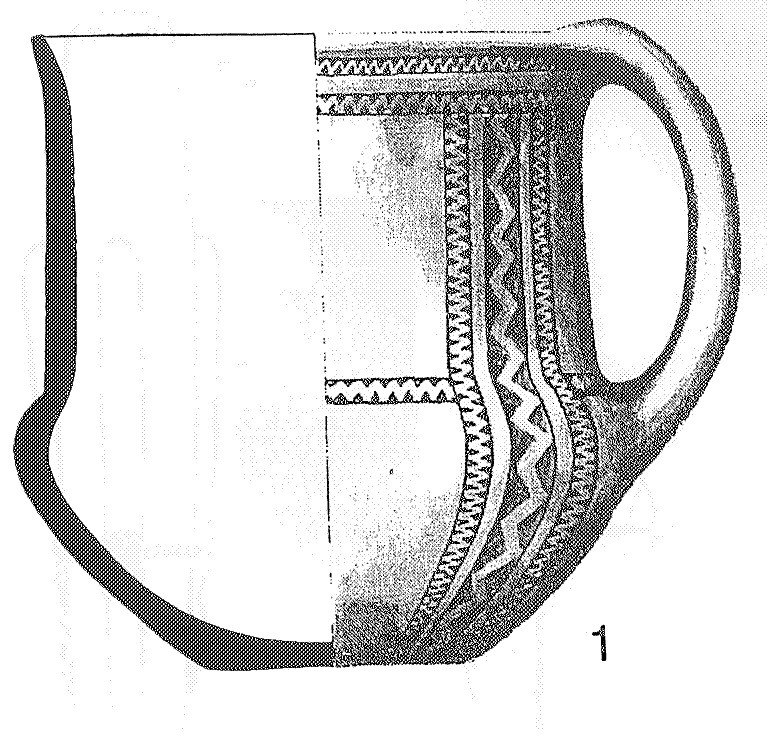

Next to the feet of the deceased, next to the eastern edge of the stone cist, archaeologists have found a set of ceramic dishes in fragments.

Obok stóp zmarłego, obok wschodniej krawędzi kamiennej komory, archeolodzy znaleźli zestaw naczyń ceramicznych w kawałkach.

First is a shallow bowl with the ring leg:

Pierwsza to płytka miska z nogą pierścieniową:

Both dishes were made from reddish brown clay and were richly decorated and polished.

Oba naczynia były wykonane z czerwonobrązowej gliny i były bogato zdobione i polerowane.

In the past when it was believed that Mala and Velika Grida tumuluses were build at the beginning of the second millennium bc, it was proposed that the culture which built these Montenegrian tumuluses was influenced by late phases of Vučedol culture. But now that we know that Velika and Mala Gruda tumuluses were contemporary with the early period of the Vučedol culture things become much more complicated and confusing.

W przeszłości, gdy uważano, że kurhany Mala i Velika Gruda zostały zbudowane na początku drugiego tysiąclecia p.n.e., sugerowano, że kultura, która zbudowała te kurhany czarnogórskie, była pod wpływem późnych faz kultury Vučedol. Ale teraz, gdy wiemy, że kurhany Velika i Mala Gruda były współczesne wczesnemu okresowi kultury Vučedol, sprawy stają się o wiele bardziej skomplikowane i mylące.

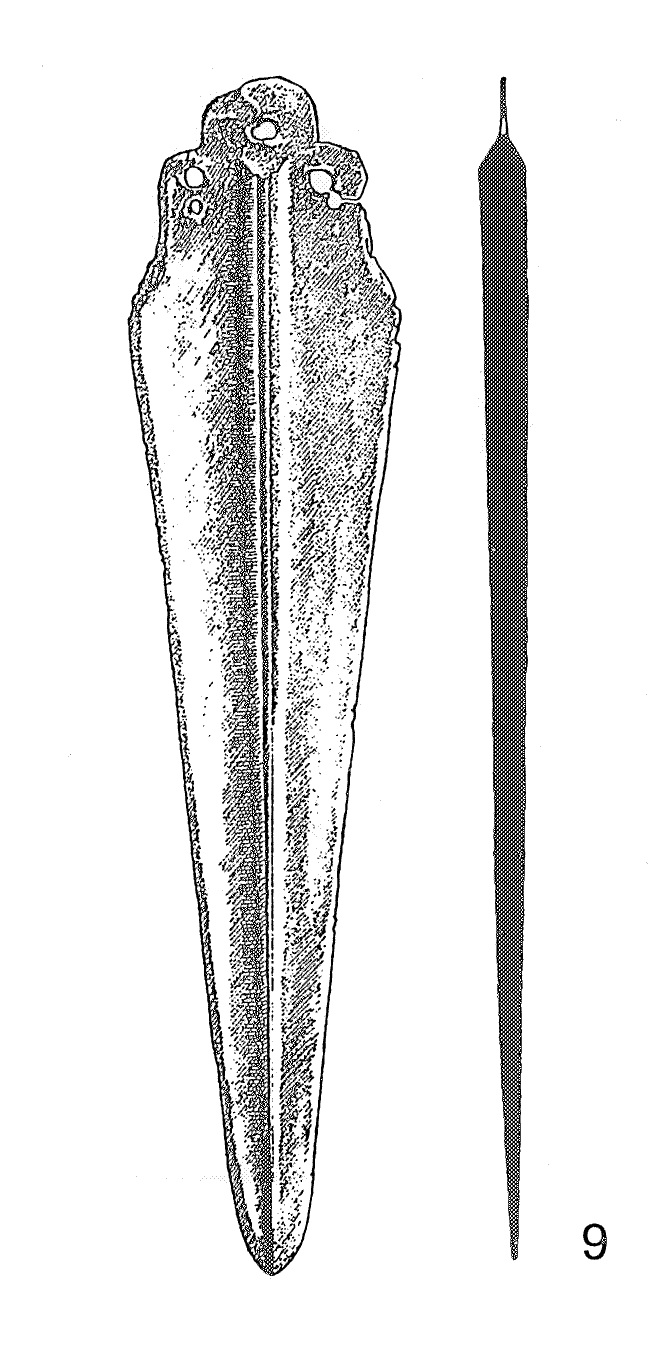

The most important artifacts were discovered at the eastern edge of the grave cist, at the waist level. These were a golden dagger and a silver axe. Actually both objects were made from complex alloys and not of pure gold and silver. Spectrographic analysis had shown that the dagger was made from the alloy of silver, gold and copper in proportion 3:2:2 and that the axe was made from the same alloy but in proportion 4:1:1.

Najważniejsze artefakty odkryto na wschodnim skraju skrzyni grobowej, na wysokości pasa. Były to złoty sztylet i srebrny topór. W rzeczywistości oba przedmioty zostały wykonane ze złożonych stopów, a nie z czystego złota i srebra. Analiza spektrograficzna wykazała, że sztylet został wykonany ze stopu srebra, złota i miedzi w proporcji 3:2:2, a topór został wykonany z tego samego stopu, ale w proporcji 4:1:1.

The golden dagger:

Złoty sztylet:

The dagger is leaf shaped with straight edges and rounded top. It has a short tong for attaching it to the handle and a triple profiled central ridge. Similar daggers are found in Anatolia dating to the mid 3rd millennium bc. Her is the Mala Gruda dagger and its Anatolian comparisons:

Sztylet ma kształt liścia z prostymi krawędziami i zaokrąglonym wierzchołkiem. Ma krótki szczypiec do przymocowania go do rękojeści i potrójnie profilowany środkowy grzbiet. Podobne sztylety znajdują się w Anatolii datowane na połowę III tysiąclecia p.n.e. Oto sztylet Mala Gruda i jego anatolijskie porównania:

1. Mala Gruda: N. TASIĆ (ed.), Praistorija Jugoslavenskih Zemalja III. Eneolitsko doba (1979) pl. 42:8.

2. Karataş: M. MELLINK, “Excavations at Karataş-Semayük 1970,” AJA 73 (1969) pl. 74:21 (drawing J. Maran) dated to 2900 – 2600 BC.

3. Bayindirköy: K. BITTEL, “Einige Kleinfunde aus Mysien und aus Kilikien,” IstMitt 6 (1955) fig. 1 dated to 2500 – 2200 BC.

4. Bayindirköy: BITTEL (supra) fig. 4 dated to 2500 – 2200 BC.

5. Alaca Höyük: STRONACH (supra n. 47) fig. 3:4 dated to 3rd millennium bc.

1. Mala Gruda: N. TASIĆ (red.), Praistorija Jugoslavenskih Zemalja III. Eneolitsko doba (1979) pl. 42:8. 2. Karataş: M. MELLINK, „Excavations at Karataş-Semayük 1970,” AJA 73 (1969) pl. 74:21 (rysunek J. Maran) datowany na 2900-2600 p.n.e. 3. Bayindirköy: K. BITTEL, „Einige Kleinfunde aus Mysien und aus Kilikien,” IstMitt 6 (1955) ryc. 1 datowany na 2500-2200 p.n.e. 4. Bayindirköy: BITTEL (supra) ryc. 4 datowany na 2500-2200 p.n.e. 5. Alaca Höyük: STRONACH (supra n. 47) ryc. 3:4 datowany na 3 tysiąclecie p.n.e.

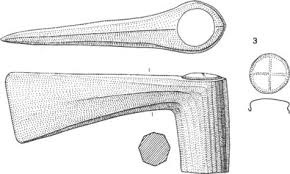

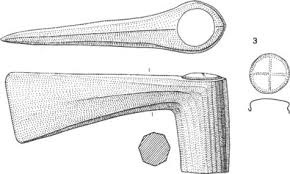

The silver axe:

Srebrny topór:

This silver axe is the last and the most important find from the Mala Gruda tumulus. For two reasons. Firstly the new dating of this axe opens some interesting questions about our understanding the chronology of the distribution of the shaft hole axes in the Balkans. Secondly the new dating of this axe opens some very interesting questions about our understanding of the Early Bronze Age Irish and British history.

Ten srebrny topór jest ostatnim i najważniejszym znaleziskiem z kurhanu Mala Gruda. Z dwóch powodów. Po pierwsze, nowe datowanie tego topora otwiera kilka interesujących pytań o nasze zrozumienie chronologii rozmieszczenia toporów z otworem trzonowym na Bałkanach. Po drugie, nowe datowanie tego topora otwiera kilka bardzo interesujących pytań o nasze zrozumienie irlandzkiej i brytyjskiej historii wczesnej epoki brązu.

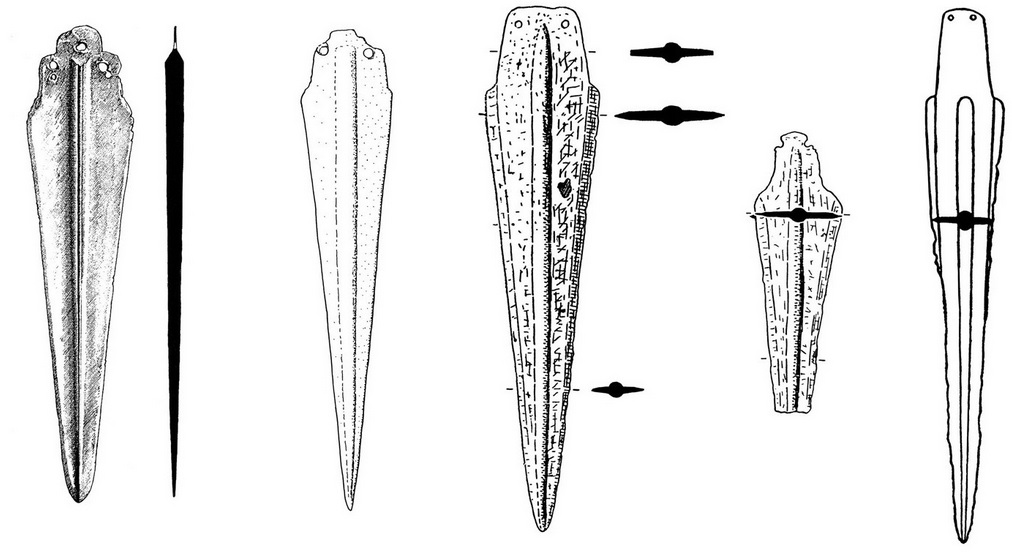

So, why is Mala Gruda axe important for our understanding the chronology of the distribution of the shaft hole axes in the Balkans?

Dlaczego więc topór Mala Gruda jest ważny dla naszego zrozumienia chronologii rozmieszczenia toporów z otworem trzonowym na Bałkanach?

The silver axe has a thin and narrow triangular blade with a cylindrical socket. In the literature we read that „this type of axe belongs to the Vučedol Kozarac type axes”. However no axes like the Mala Gruda axe have been found in Vučedol culture.

Srebrny topór ma cienkie i wąskie trójkątne ostrze z cylindrycznym gniazdem. W literaturze czytamy, że „ten typ topora należy do toporów typu Vučedol Kozarac”. Jednak w kulturze Vučedol nie znaleziono żadnych toporów takich jak topór Mala Gruda.

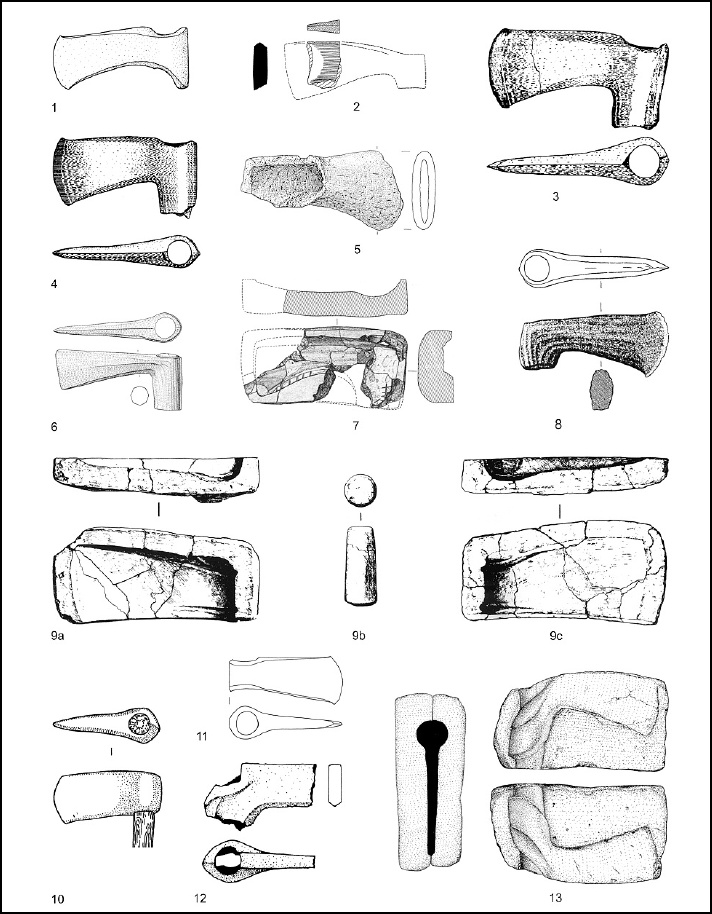

Shape wise Mala gruda axe does look like Vučedol culture axes with one blade and a cylindrical extension for a handle haft. These type of axes were exported to the Eastern Mediterranean including to Troy via Lemnos. This is a picture of a hoard of such axes from Brekinjska (Pakrac) in Croatia.

Jeśli chodzi o kształt, topór Mala gruda wygląda jak topory kultury Vučedol z jednym ostrzem i cylindrycznym przedłużeniem trzonu. Tego typu topory eksportowano do wschodniej części Morza Śródziemnego, w tym do Troi przez Lemnos. To jest zdjęcie skarbu takich toporów z Brekinjska (Pakrac) w Chorwacji.

However the axe from Mala Gruda tumulus is of an exceptional quality and made of Gold + Silver + Copper alloy and not bronze. Silver axes were found in Vučedol site of Stari Jankovci.

Jednak topór z kurhanu Mala Gruda jest wyjątkowej jakości i wykonany ze stopu złota + srebra + miedzi, a nie brązu. Srebrne topory znaleziono w Vučedol w Stari Jankovci.

You can read about them in this Croatian article and this English article. The Stari Jankovci axes are also silver shaft-hole axes, but their shape is completely different from the shape of the Mala Gruda axe. So we can’t talk about direct link between these Vučedol silver axes and the silver axe from Mala Gruda. However this shows that both the knowledge how to make Mala Gruda type axe shape and material existed in the Vučedol culture, so we can say that it is possible the people who made the Mala Gruda axe were influenced by the Vučedol culture. So we could say that the Mala Gruda axe could have indeed been made by Vučedol metalworkers. Except that the site where the above two silver axes ware found was dated to 2500 – 2040 BC wheres Mala Gruda was dated to 2800 – 2700 BC. This means that the Mala Gruda axe is hundreds of years older. This is a very good article on the dating of the Vučedol culture sites .This opens a big question: who influenced who? Who learned from who?

Możesz o nich przeczytać w tym chorwackim artykule i tym angielskim artykule. Siekiery Stari Jankovci są również srebrnymi siekierami z otworami trzonowymi, ale ich kształt jest zupełnie inny od kształtu topora Mala Gruda. Nie możemy więc mówić o bezpośrednim związku między tymi srebrnymi siekierami z Vučedol a srebrnym toporem z Mala Gruda. Jednak pokazuje to, że zarówno wiedza, jak i materiał na wykonanie topora typu Mala Gruda istniały w kulturze Vučedol, więc możemy powiedzieć, że możliwe jest, że ludzie, którzy wykonali topór Mala Gruda, byli pod wpływem kultury Vučedol. Więc możemy powiedzieć, że topór Mala Gruda mógł być rzeczywiście wykonany przez metalurgow z Vučedol. Z wyjątkiem tego, że stanowisko, w którym znaleziono dwa powyższe srebrne topory, datowano na 2500 – 2040 p.n.e., podczas gdy Mala Gruda datowana jest na 2800 – 2700 p.n.e. Oznacza to, że siekiera Mala Gruda jest o setki lat starsza. To bardzo dobry artykuł na temat datowania stanowisk kultury Vučedol. To otwiera duże pytanie: kto na kogo wpłynął? Kto się od kogo uczył?

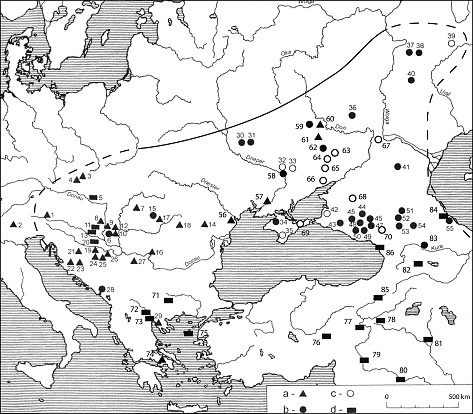

It is assumed that the earliest shaft-hole axes were developed in the the north Caucasus by the Maikop culture sometime between 3500 and 3128 BC.

Przyjmuje się, że najwcześniejsze topory z otworami trzonowymi zostały opracowane na północnym Kaukazie przez kulturę Majkop w latach 3500–3128 p.n.e.

From here they spread within few hundred years to a large area in Central and Western Asia and Eastern and Central Europe and the Balkans.

Stąd rozprzestrzeniły się w ciągu kilkuset lat na duży obszar w Azji Środkowej i Zachodniej, Europie Wschodniej i Środkowej oraz na Bałkanach.

This picture shops main types of shaft-hole axes and axe molds from the above distribution area from the period late fourth millennium bc – early third millennium bc:

Na tym zdjęciu przedstawiono główne typy toporów z otworami trzonowymi i formy toporów z powyższego obszaru dystrybucji z okresu od końca czwartego tysiąclecia p.n.e. do początku trzeciego tysiąclecia p.n.e.:

Aegean: 1 Thebes, 2 Servia, 3 Petralona, 4 Triadi, 5 Poliochni;Montenegro: 6 Mala Gruda;

Hungary: 7 Zók-Várhegy;

Rumania: 8 Virgis;

North Caucasus: 9 Lebedi, 10 Novosvobodnaya/Klady;

Daghestan: 11 Velikent;

East Anatolia: 12 Arslantepe, 13 Norşuntepe.

Egejskie: 1 Teby, 2 Serbskie, 3 Petralona, 4 Triady, 5 Poliochni; Czarnogóra: 6 Mala Gruda; Węgry: 7 Zók-Várhegy; Rumunia: 8 Virgis; Północny Kaukaz: 9 Lebedi, 10 Novosvobodnaya/Klady; Dagestan: 11 Velikent; Wschodnia Anatolia: 12 Arslantepe, 13 Norşuntepe.

„…The earliest axes in Southeastern Europe are assumed to be the Baniabic type (Vîlcele) axes because their blade is not differentiated from the shaft. The upper edge of the axe is straight, while in the case of the axes of the Fajsz type and Corbasca type this edge is convex. At least some of the axes can be dated to the early Vučedol Culture (c. 31th – 28th century BC). The problem is that this dating is based on the fact that their shape is generally comparable to axes or moulds for axes from the northern Caucasus and Koban region, like the mold from Lebedi or from the Kura-Araxes Culture which were dated to that period. But the type is so simply shaped that even comparisons to much later axes are possible, and this makes the dating of the Baniabic type axes uncertain. The southeast European types of Dumbrăvioara, Izvoarele, Darabani and Kozarac have short shaft tubes and can be grouped to the second morphological trend. In some cases their tubes are faceted or ribbed. This feature is also found on one axe from the hoard of Stublo (Steblivka) in the western Ukraine. These types can be dated mainly to the earlier half of the third millennium BC…. ”

„…Najwcześniejsze topory w Europie Południowo-Wschodniej są uważane za topory typu baniabickiego (Vîlcele), ponieważ ich ostrze nie jest odróżnione od trzonu. Górna krawędź topora jest prosta, podczas gdy w przypadku topora typu Fajsz i Corbasca krawędź ta jest wypukła. Przynajmniej niektóre topory można datować na wczesną kulturę Vučedol (ok. 31–28 w. p.n.e.). Problem polega na tym, że datowanie to opiera się na fakcie, że ich kształt jest ogólnie porównywalny z toporami lub formami topora z północnego Kaukazu i regionu Koban, takimi jak forma z Lebedi lub z kultury Kura-Araxes, które datowano na ten okres. Ale typ ma tak prosty kształt, że możliwe są nawet porównania do znacznie późniejszych topora, co sprawia, że datowanie topora typu baniabickiego jest niepewne. Południowo-wschodnioeuropejskie typy Dumbrăvioara, Izvoarele, Darabani i Kozarac mają krótkie rurki trzonu i można je zaliczyć do drugiego trendu morfologicznego. W niektórych przypadkach ich rurki są fasetowane lub żebrowane. Tę cechę można znaleźć również na jednym toporze ze skarbu Stublo (Steblivka) w zachodniej Ukrainie. Tego typu topory można datować głównie na wczesną połowę trzeciego tysiąclecia p.n.e. … „

So Vučedol culture Kozarac type axes are dated to the same period to which the Mala Gruda tumulus axe was dated. So is it possible that the Mala Gruda axe predates the Vučedol culture Kozarac type axes? And is it possible that knowledge how to make this type of axes was transferred from the South of the Balkans up North and not the other way round?

Tak więc topory typu Kozarac kultury Vučedol są datowane na ten sam okres, na który datowany jest topory typu Mala Gruda. Czy zatem możliwe jest, że topory typu Kozarac kultury Vučedol są starsze od toporów typu Kozarac kultury Vučedol? I czy możliwe jest, że wiedza o tym, jak wykonać ten typ topora, została przeniesiona z południa Bałkanów na północ, a nie odwrotnie?

Finally why is Mala Gruda axe so important for our understanding of the Early Bronze Age Irish and British history?

Na koniec, dlaczego topory Mala Gruda są tak ważne dla naszego zrozumienia irlandzkiej i brytyjskiej historii wczesnej epoki brązu?

According to the archaeological data, a new people appeared out of nowhere on the Atlantic coast of Europe around the mid 3rd millennium BC: The Bell Beaker people. The Wiktionary says: „Bell Beaker is a complex cultural phenomenon involving metalwork in copper, gold and later bronze, archery, specific types of ornamentation and shared ideological, cultural and religious ideas….Several proposals have been made as to the origins of the Bell Beaker culture, notably the Iberian peninsula, the Netherlands and Central Europe. And debates are still continuing. Archaeologists and historians are still debating whether the spread of Beaker culture was due to the migration of people or spread of ideas or both…”.

Według danych archeologicznych, nowy lud pojawił się znikąd na atlantyckim wybrzeżu Europy około połowy trzeciego tysiąclecia p.n.e.: Ludzie pucharów dzwonowatych. Wiktionary mówi: „Puchary dzwonowate to złożone zjawisko kulturowe obejmujące obróbkę metalu z miedzi, złota, a później brązu, łucznictwo, określone rodzaje ozdób i wspólne idee gospodarcze, kulturowe i religijne…. Przedstawiono kilka propozycji dotyczących pochodzenia kultury pucharów dzwonowatych, zwłaszcza Półwyspu Iberyjskiego, Holandii i Europy Środkowej. A debaty wciąż trwają. Archeolodzy i historycy wciąż debatują, czy rozprzestrzenienie się kultury pucharów dzwonowatych było spowodowane migracją ludzi, rozprzestrzenianiem się idei, czy też jednym i drugim…”.

Well for Ireland we know that the arrival of the Beaker culture was due to the arrival of the Beaker people. Before 2500 BC there was no metalwork in Ireland and no beakers. After 2500 BC there was as thriving sophisticated metalworking culture in Ireland and beakers. That can only happen if we have an influx of people with metalworking skills into Ireland around 2500 BC. And archaeologists and historians all agree on this. But where did these metalworking beaker using new Irish come from and who they were is „a mystery”.

Cóż, jeśli chodzi o Irlandię, wiemy, że przybycie kultury pucharów dzwonowatych było spowodowane przybyciem ludzi pucharów dzwonowatych. Przed 2500 r. p.n.e. w Irlandii nie było obróbki metali ani pucharów. Po 2500 r. p.n.e. w Irlandii istniała równie prężnie rozwijająca się kultura obróbki metali i pucharów. Może się to zdarzyć tylko wtedy, gdy około 2500 r. p.n.e. do Irlandii napłynie ludność z umiejętnościami obróbki metali. Archeolodzy i historycy zgadzają się co do tego. Ale skąd pochodzą ci nowi Irlandczycy, którzy zajmują się obróbką metali i kim byli, to „zagadka”.

So what can the Irish annals tell us about the arrival of the Beaker people to Ireland?

Więc co Irlandzkie annały mówią nam o przybyciu ludu pucharów dzwonowatych do Irlandii?

Well the old Irish annals don’t talk about Bell Beaker people of course. But they tell us that: „…after the flood, came Partholón with his people…” The Annals of the Four Masters says that Partholóin arrived in in Ireland 2520 Anno Mundi (after the „creation of the world”), Seathrún Céitinn’s Foras Feasa ar Érinn says they arrived in 2061 BC, Annals of Four Masters says that they arrived at 2680 BC. So Sometimes in the second half of the 3rd millennium.

Cóż, stare irlandzkie annały oczywiście nie wspominają o ludziach pucharów dzwonowatych. Ale mówią nam, że: „…po potopie, przybył Partholón ze swoim ludem…” Roczniki Czterech Mistrzów mówią, że Partholón przybył do Irlandii w 2520 Anno Mundi (po „stworzeniu świata”), Foras Feasa ar Érinn Seathrúna Céitinna mówi, że przybyli w 2061 p.n.e., Roczniki Czterech Mistrzów mówią, że przybyli w 2680 p.n.e. Więc czasami w drugiej połowie III tysiąclecia.

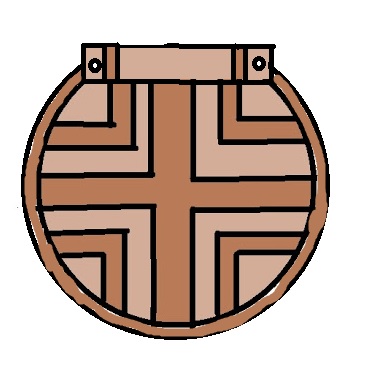

Partholón and his people are credited with introducing cattle husbandry, plowing, cooking, dwellings, trade, and dividing the island in four and most importantly for this story, they are credited with bringing gold which before them was not used in Ireland. As I already said in my post about the Irish gold, this has was actually confirmed by the archaeological finds from Ireland. Some people came to Ireland around the 2500 BC or there after, and brought with them copper metalworking knowledge. They opened the first copper mine in Ireland in Ross Island and started making copper axes. The archaeologists originally believed that these immigrant copper metalworkers also started mining gold in Ireland. And that they used that gold to make golden ornaments. The reason for this belief is that around the same time when the Beaker copper metalworkers arrived to Ireland, we suddenly see gold being used for making ornaments, mostly gold lunulae, about which I wrote in my post about the Irish Gold, and gold cross discs like these ones:

But as I already said in my post about the Irish gold, it turns out that the gold from which the Irish lunulae and cross discs were made was not mined in Ireland, but that it was brought into Ireland from somewhere else. Archaeologists are now saying that the gold was brought into Ireland from Cornwall. The local Irish craftsmen then used it to make the lunulae and cross discs. In my post about the Irish gold I argued that these gold ornaments were probably not made in Ireland from imported gold, but that they were made wherever the gold was mined and smelted (Cornwall???), and that the finished gold lunulae and cross discs were imported into Ireland.

Ale jak już wspomniałem w swoim poście o irlandzkim złocie, okazuje się, że złoto, z którego wykonano irlandzkie lunule i dyski krzyżowe, nie zostało wydobyte w Irlandii, ale zostało przywiezione do Irlandii z innego miejsca. Archeolodzy twierdzą teraz, że złoto zostało przywiezione do Irlandii z Kornwalii. Lokalni irlandzcy rzemieślnicy użyli go do wykonania lunuli i dysków krzyżowych. W moim poście o irlandzkim złocie argumentowałem, że te złote ozdoby prawdopodobnie nie zostały wykonane w Irlandii z importowanego złota, ale że zostały wykonane wszędzie tam, gdzie złoto było wydobywane i przetapiane (Kornwalia???), a gotowe złote lunulae i dyski krzyżowe zostały zaimportowane do Irlandii.

The archaeologists believed that these types of ornaments originated in Ireland because they have no precedence in Europe. Until the discovery that the gold from which these ornaments were made did not come from Ireland but from Cornwall. Now they believe that these types of ornaments originated in Ireland or Britain. And I would agree with them when it comes to lunulae. So far there is no precedence for this type of gold ornaments. But I have to say that now we have a proof that the golden cross discs did not originate in Ireland or Britain. I can say this because now we know that hundreds of years before these gold cross discs appeared in the British isles, they were made and used in the Balkans, more precisely in Montenegro.

Archeolodzy uważali, że tego typu ozdoby pochodzą z Irlandii, ponieważ nie mają precedensu w Europie. Aż do odkrycia, że złoto, z którego wykonano te ozdoby, nie pochodziło z Irlandii, ale z Kornwalii. Teraz uważają, że tego typu ozdoby pochodzą z Irlandii lub Wielkiej Brytanii. I zgodziłbym się z nimi, jeśli chodzi o lunule. Jak dotąd nie ma precedensu dla tego typu złotych ozdób. Ale muszę powiedzieć, że teraz mamy dowód na to, że złote dyski krzyżowe nie pochodzą z Irlandii ani Wielkiej Brytanii. Mogę to powiedzieć, ponieważ teraz wiemy, że setki lat przed pojawieniem się tych złotych krzyży na Wyspach Brytyjskich, były one wytwarzane i używane na Bałkanach, a dokładniej w Czarnogórze.

Have a look again at the silver axe from Mala Gruda tumulus.

Spójrzmy jeszcze raz na srebrny topór z kurhanu Mala Gruda.

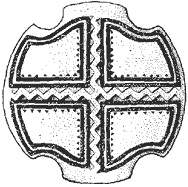

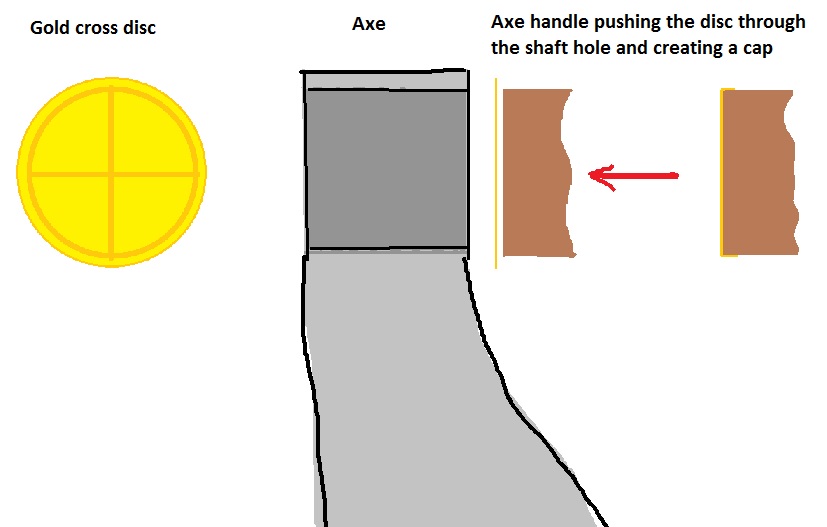

This silver axe was found together with a strange golden cap covering the the top of the axe shaft. The cap was made from a golden disk which is a thin embossed sheet of gold with a cross at the centre, surrounded by a circle.

Ten srebrny topór został znaleziony razem z dziwną złotą nasadką pokrywającą górną część trzonu topora. Nasadka została wykonana ze złotego dysku, który jest cienką tłoczoną warstwą złota z krzyżem pośrodku, otoczonym okręgiem.

The design on the gold disc cap resembles the most the design found on the gold sun disc which was found in a burial mound at Monkton Farleigh, just over 20 miles from Stonehenge, in 1947 along with a pottery beaker, flint arrowheads and fragments of the skeleton of an adult male.

Wzór na złotej nasadce dysku najbardziej przypomina wzór na złotym dysku słonecznym, który został znaleziony w kurhanie w Monkton Farleigh, nieco ponad 20 mil od Stonehenge, w 1947 roku wraz z glinianym kubkiem, krzemiennymi grotami strzał i fragmentami szkieletu dorosłego mężczyzny.

The two pence piece sized gold disc was made in about 2,400 BC, soon after the Sarsen stones were put up at Stonehenge, and is thought to represent the sun.It was kept safe by the landowner since its discovery and has only now been given to the Museum. The disk is a thin embossed sheet of gold with a cross at the centre, surrounded by a circle, and between the lines of both the cross and the circle are fine dots which glint in sunlight.

Złoty krążek wielkości dwóch pensów został wykonany około 2400 r. p.n.e., wkrótce po ustawieniu kamieni Sarsen w Stonehenge, i uważa się, że przedstawia słońce. Był bezpiecznie przechowywany przez właściciela ziemi od momentu odkrycia i dopiero teraz został przekazany Muzeum. Krążek jest cienką tłoczoną płytą złota z krzyżem pośrodku, otoczonym okręgiem, a między liniami krzyża i okręgu znajdują się drobne kropki, które błyszczą w świetle słonecznym.

The golden cross discs found in Ireland and Britain were all dated to 2400 BC – 2100 BC. The golden cross disc from Mala Gruda was originally dated to the period 1900 to 1800 BC. I believe that this is why no one before made a connection between the Mala Gruda golden cross disc and the cross discs found in Ireland and Britain. Even if someone did make a connection, the Mala Grida golden cross disc was probably classified as being made under the influence of the late Beaker culture. However the latest dating pushes the date when Mala Gruda tumulus was built almost 1000 years back into the past, to the period between 2800 to 2700 BC. Now this changes everything. Someone in Montenegro was making golden cross discs 300 – 400 years before the first such disc appeared in Ireland and Britain. The thing is that this golden cross disc from Mala Gruda has no precedence. Except for another golden cross disc which was used in the same way, for making the axe shaft cap. And this other golden cross disc was found in an even older Montenegrian tumulus, which was dated to the end of the 4th – beginning of the 3rd millennium bc and which was linked directly to the late Yamna culture. I will write about this tumulus in one of my next posts. This means that we can say that unless new archaeological data emerges, the origin of these golden cross disc ornaments is in the early 3rd millennium BC Montenegrian tumulus building culture.

Wszystkie złote krzyże znalezione w Irlandii i Wielkiej Brytanii datowano na lata 2400–2100 p.n.e. Złoty krzyż z Mala Gruda pierwotnie datowano na okres 1900–1800 p.n.e. Uważam, że dlatego nikt wcześniej nie powiązał złotego krzyża z Mala Gruda z krzyżami znalezionymi w Irlandii i Wielkiej Brytanii. Nawet jeśli ktoś powiązał, złoty krzyż z Mala Grida został prawdopodobnie sklasyfikowany jako wykonany pod wpływem późnej kultury pucharów pucharowych. Jednak najnowsze datowanie przesuwa datę budowy kopca Mala Gruda o prawie 1000 lat wstecz, na okres między 2800 a 2700 rokiem p.n.e. Teraz to wszystko zmienia. Ktoś w Czarnogórze robił złote krzyże 300-400 lat przed pojawieniem się pierwszego takiego dysku w Irlandii i Brytanii. Rzecz w tym, że ten złoty krzyż z Mala Gruda nie ma precedensu. Z wyjątkiem innego złotego krzyża, który był używany w ten sam sposób, do wykonania nasadki na trzon topora. I ten inny złoty krzyż na dysku został znaleziony w jeszcze starszym czarnogórskim kurhanie, datowanym na koniec IV – początek III tysiąclecia p.n.e. i bezpośrednio powiązanym z późną kulturą Jamna. O tym kurhanie napiszę w jednym z moich następnych postów. Oznacza to, że możemy powiedzieć, że o ile nie pojawią się nowe dane archeologiczne, pochodzenie tych złotych krzyżykowych ozdób znajduje się we wczesnym III tysiącleciu p.n.e. czarnogórskiej kulturze budowy kurhanów.

Now the big question: Is it possible that people who made these golden cross discs in Montenegro or their descendants, were the same people who later made the golden cross discs in Ireland and Britain? Was there a migration from Montenegro to British Isles around the middle of the 3rd millennium BC? I believe so. And guess what, the Irish annals says so too. But I will talk about this more in one of my next posts.

Teraz najważniejsze pytanie: Czy możliwe jest, że ludzie, którzy wykonali te złote krzyże w Czarnogórze lub ich potomkowie, byli tymi samymi ludźmi, którzy później wykonali złote krzyże w Irlandii i Brytanii? Czy nastąpiła migracja z Czarnogóry na Wyspy Brytyjskie mniej więcej w połowie III tysiąclecia p.n.e.? Myślę, że tak. I zgadnijcie co, irlandzkie annały również tak mówią. Ale opowiem o tym więcej w jednym z moich następnych postów.

Until then stay happy and keep smiling.

Do tego czasu bądźcie szczęśliwi i uśmiechajcie się.

źródło: https://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2015/09/mala-i-velika-gruda-tumuluses.html