Bullaun stones (Kamienie Bullauna)

In my post about eating acorns, I said that people had to invent quite a few things in order to move from eating acorns as occasional snacks to eating acorns as staple starch food. One of these acorn eating inspired inventions was a grinding stone. In archaeology, a grinding slab, or grinding stone is a stone artifact generally used to grind various materials into usable size crumbs, though some grinding slabs were used to shape other ground stone artifacts. Some grinding stones are portable; others are not and, in fact, may be part of a stone outcropping. The grinding slabs or grinding stones work through crushing and scraping actions produced by the motion of the movable part, pestle, over the static part, mortar. Any matter which is softer than the material from which the mortar and pestle are made and which is not viscose, will be crushed or scraped into progressively smaller bits. The longer you apply the grinding motion the finer the bits become. Grinding stones are made of large-grained materials such as granite, basalt, or similar tool stones.

W moim poście o jedzeniu żołędzi powiedziałem, że ludzie musieli wymyślić sporo rzeczy, aby przejść od jedzenia żołędzi jako okazjonalnych przekąsek do jedzenia żołędzi jako podstawowego pożywienia skrobiowego. Jednym z tych wynalazków inspirowanych jedzeniem żołędzi był kamień szlifierski. W archeologii płyta szlifierska lub kamień szlifierski jest kamiennym artefaktem powszechnie używanym do mielenia różnych materiałów na okruchy o użytecznej wielkości, chociaż niektóre płyty szlifierskie były używane do kształtowania innych artefaktów z kamienia szlifowanego. Niektóre kamienie szlifierskie są przenośne; inne nie są iw rzeczywistości mogą być częścią wychodni skalnej. Płyty mielące lub kamienie mielące działają poprzez działania miażdżące i zgarniające wywołane ruchem części ruchomej, tłuczka, nad częścią statyczną, moździerzem. Każda materia, która jest bardziej miękka niż materiał, z którego wykonany jest moździerz i tłuczek i która nie jest wiskozą, zostanie zmiażdżona lub rozskrobana na coraz mniejsze kawałki. Im dłużej stosujesz ruch szlifowania, tym drobniejsze stają się ziarna. Kamienie szlifierskie są wykonane z materiałów gruboziarnistych, takich jak granit, bazalt lub podobne kamienie narzędziowe.

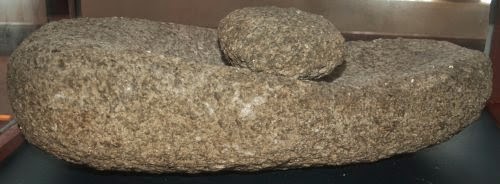

There are two general types of grinding stones: saddle and cup (conical) grinding stone.

Istnieją dwa ogólne rodzaje kamieni szlifierskich: kamień szlifierski siodłowy i stożkowy / kubkowy.

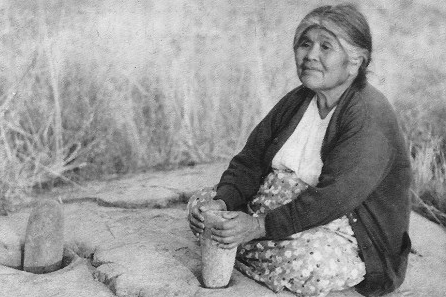

This is an example of a saddle grinding stone from Ojibwe tribe from the Great Lakes area USA:

Oto przykład siodłowego kamienia do szlifowania z plemienia Ojibwe z obszaru Wielkich Jezior USA:

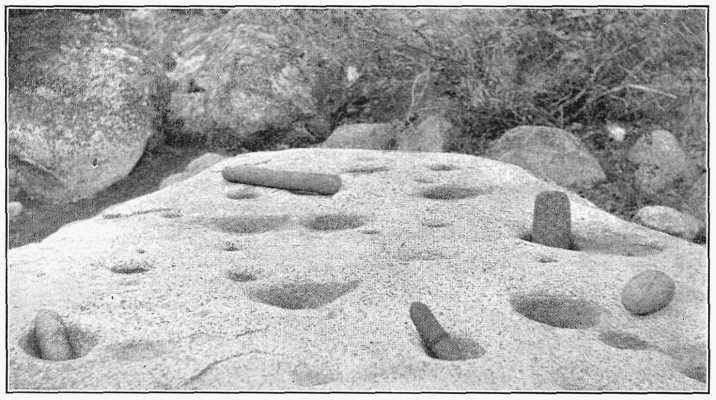

This is an example of a cup grinding stone from Mariposa county in California USA:

Oto przykład kamienia kubkowego (stożkowego) do szlifowania z hrabstwa Mariposa w Kalifornii w USA:

This is an example of a combined saddle and cup grinding stone. The hole in the rock was used like cup grinding stone and the flat surface around it was used like a saddle grinding stone.

To jest przykład połączonego kamienia do szlifowania siodłowego i kubkowego. Otwór w skale był używany jako kubkowy kamień do szlifowania, a płaska powierzchnia wokół niego była używana jako sidołowy kamień do szlifowania.

On the next picture you can see a large boulder communal grinding stone. These types of grinding stones are also a combination of the saddle and cup grinding stones with multiple conical grinding holes surrounded with flat surfaces used as saddle grinding stones. Here is a great example of a communal grinding stone from Yosemite national park:

Na kolejnym zdjęciu widać duży plemienny głaz – kamień szlifierski. Te rodzaje kamieni szlifierskich są również połączeniem kamieni szlifierskich siodłowych i kubkowych z wieloma stożkowymi otworami szlifierskimi otoczonymi płaskimi powierzchniami używanymi jako kamienie szlifierskie siodłowe. Oto świetny przykład wspólnego kamienia szlifierskiego z Parku Narodowego Yosemite:

In this great documentary film called Kumeyaay story „Life Under the Oaks”, Kumeyaay people talk about gathering, processing and eating acorn while using one of the boulder communal acorn grinding sites.

In this great documentary film called Kumeyaay story „Life Under the Oaks”, Kumeyaay people talk about gathering, processing and eating acorn while using one of the boulder communal acorn grinding sites.W tym wspaniałym filmie dokumentalnym zatytułowanym „Życie pod dębami” Kumeyaay ludzie opowiadają o zbieraniu, przetwarzaniu i jedzeniu żołędzi podczas korzystania z jednego z głazowych miejsc mielenia żołędzi.

For thousands of years Native American women all over America ground acorns, nuts, and later maize (corn) with grinding stones like the ones shown on the above pictures. Here is a picture of an old Indian woman preparing acorn meal from „The Algonquian Confederacy of the Quinnipiac Tribal Council” website.

So you can see that Native americans used both cup (conical) and flat saddle grinding stones for grinding acorns.

Widać więc, że rdzenni Amerykanie używali do mielenia żołędzi zarówno kubkowych (stożkowych), jak i płaskich kamieni siodłowych.

As I said in my post about eating acorns I believe that the invention of the grinding stones was a byproduct of the invention of the acorn breaking and leaching process. The people trying to quickly leach acorns for food needed to first shell the acorns. Breaking the acorn shell and separating the acorn from the shell is the most difficult part of acorn food preparation. Acorns have an elastic shell that resists slow sideways pressure. The best way to break the acorns shell is to put the flat end (the side that used to have the cap) on a firm surface and hit the pointy end with a stone. This process of breaking the acorn shells often resulted in broken and crushed acorns. I believe that people leaching acorns would have gathered whole and broken acorns and leached them together. And they would very quickly notice that the crushed pieces leached quicker, and that smaller the bits are the quicker the leaching is. So people would start crushing all the acorns before leaching. While crushing the acorns, people noticed that just whacking the acorns with a stone scattered the bits everywhere. But if they gently broke the shell, took the acorn out, placed it on a flat stone, and then pressed the acorn with another stone and moved the pressing stone in a scraping, grinding motion over the acorn, all the bits would stay on the bottom flat stone. I believe that this is how grinding was invented.

Jak powiedziałem w moim poście o jedzeniu żołędzi, uważam, że wynalazek kamieni mielących był produktem ubocznym wynalezienia procesu łamania i wypłukiwania żołędzi. Ludzie próbujący szybko wypłukiwać żołędzie na jedzenie, musieli najpierw obrać żołędzie. Łamanie skorupy żołędzia i oddzielanie żołędzia od skorupy jest najtrudniejszą częścią przygotowywania żywności z żołędzi. Żołędzie mają elastyczną skorupę, która jest odporna na powolny nacisk boczny. Najlepszym sposobem na rozbicie skorupy żołędzi jest położenie płaskiego końca (strony, na której była czapka) na twardej powierzchni i uderzenie kamieniem w ostry koniec. Ten proces łamania łusek żołędzi często dawał w efekcie połamane i zmiażdżone żołędzie. Wierzę, że ludzie wypłukujący żołędzie zbierali całe i połamane żołędzie i wypłukiwali je razem. I bardzo szybko zauważyliby, że pokruszone kawałki wypłukiwały się szybciej, a im mniejsze kawałki, tym szybsze wypłukiwanie. Więc ludzie zaczęliby miażdżyć wszystkie żołędzie przed wypłukiwaniem. Podczas miażdżenia żołędzi ludzie zauważyli, że samo walenie w żołędzie kamieniem rozrzucało kawałki na wszystkie strony. Ale jeśli delikatnie złamali skorupę, wyjęli żołądź, położyli go na płaskim kamieniu, a następnie przycisnęli żołądź innym kamieniem i przesunęli kamień dociskowy ruchem drapania, tarcia po żołędziu, wszystkie kawałki pozostałyby na powierzchni dolnego płaskiego kamienia. Myślę, że tak właśnie wymyślono szlifowanie.

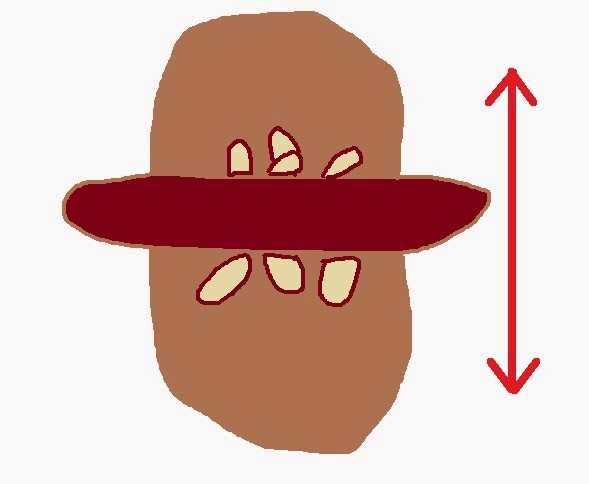

This is the grinding motion used for grinding on a saddle grinding stone:

Jest to ruch szlifowania używany do szlifowania na siodłowym kamieniu do szlifowania:

People who were crushing and grinding acorns soon noticed that if the mortar stone had a cup like hole, then you could crush the acorns and grind them coarsely quickly without bits flying everywhere. People also realised that if the mortar stone had a cup like hole, they could use rotating grinding motion which is also much more efficient.

Ludzie, którzy miażdżyli i mielili żołędzie, wkrótce zauważyli, że jeśli kamień podstawy miał otwór przypominający kielich, można było zmiażdżyć żołędzie i zmielić je na grubo szybko, bez latających wszędzie odprysków. Ludzie zdali sobie również sprawę, że gdyby kamień podstawy miał otwór podobny do kubka, mogli użyć obrotowego ruchu szlifierskiego, który jest również znacznie bardziej wydajny.

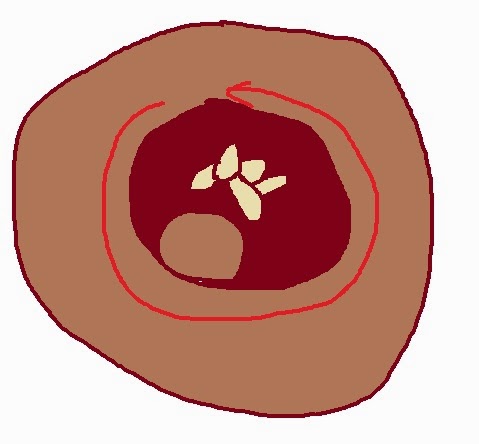

This is the grinding motion used for grinding on a cup grinding stone:

As I said in my post about the acorns in archaeology, the earliest grinding stones are all associated with the acorn eating cultures. At the moment the earliest dated grinding stones were found in Upper Paleolithic sites in China (found to have been used for grinding plant food including acorns) and in Mesolithic sites in Morocco and Levant (found to have been used for grinding plant food including acorns). But I firmly believe that even earlier ones will be found. Also the latest paleobotanical data actually confirms that the food traces found on the grinding stones found in a lot of early „agricultural” sites were actually of acorns, which meant that the grinding stones in these societies were primarily used for grinding acorns.

Jak powiedziałem w moim poście o żołędziach w archeologii, wszystkie najwcześniejsze kamienie szlifierskie są związane z kulturami jedzenia żołędzi. W tej chwili najwcześniejsze datowane kamienie do mielenia znaleziono na stanowiskach górnego paleolitu w Chinach (stwierdzono, że były używane do mielenia pokarmu roślinnego, w tym żołędzi) oraz na stanowiskach mezolitycznych w Maroku i Lewancie (stwierdzono, że były używane do mielenia pokarmu roślinnego, w tym żołędzi) . Ale mocno wierzę, że zostaną znalezione jeszcze wcześniejsze. Również najnowsze dane paleobotaniczne faktycznie potwierdzają, że ślady pożywienia znalezione na kamieniach do mielenia odkrytych na wielu wczesnych stanowiskach „rolniczych” były w rzeczywistości śladami żołędzi, co oznaczało, że kamienie mielące w tych społeczeństwach były głównie używane do mielenia żołędzi.

But once the grinding stone was invented as a tool for grinding acorns, people quickly realised that it can be used for grinding other things. Ethnographic evidence and ancient historical texts show that a wide range of foodstuffs and inorganic materials were processed using grinding stones (or as they are also known as, querns or mortars), including nuts, seeds, fruit, vegetables, herbs, spices, meat, bark, pigments, temper and clay. Grinding stones were also widely used in grinding metal ores after mining extraction. The aim was to liberate fine ore particles which could then be separated by washing for example, prior to smelting. Also, finely ground ore requires smaller fire to be heated and melted which makes it easier and faster to transform it into molten metal in primitive smelting pits. The earliest example of use of mortars in metallurgy can be found in Vinča culture where grinding stones were used for grinding cinnabar ore. One of the earliest uses for grinding stones was probably for the manufacturing of ochre and other pigments. You can read how this was done in this great article entitled „How to paint a mammoth„.

Kiedy kamień szlifierski został wynaleziony jako narzędzie do mielenia żołędzi, ludzie szybko zdali sobie sprawę, że można go używać do mielenia innych rzeczy. Dowody etnograficzne i starożytne teksty historyczne wskazują, że przy użyciu kamieni mielących (lub jak inaczej się je nazywa żarna lub moździerze) przetwarzano szeroką gamę środków spożywczych i materiałów nieorganicznych, w tym orzechy, nasiona, owoce, warzywa, zioła, przyprawy, mięso, korę, pigmenty, ziarno i glinę. Kamienie szlifierskie były również szeroko stosowane do mielenia rud metali po wydobyciu górniczym. Celem było uwolnienie drobnych cząstek rudy, które można następnie oddzielić przez przemywanie, na przykład przed wytopem. Również drobno zmielona ruda wymaga mniejszego ognia do podgrzania i stopienia, co ułatwia i przyspiesza jej przekształcenie w stopiony metal w prymitywnych dołach hutniczych. Najwcześniejszy przykład zastosowania moździerzy w metalurgii można znaleźć w kulturze Vinča, gdzie do mielenia rudy cynobru używano kamieni szlifierskich. Jednym z najwcześniejszych zastosowań kamieni szlifierskich była prawdopodobnie produkcja ochry i innych pigmentów. Możesz przeczytać, jak to zrobiono w tym świetnym artykule zatytułowanym „Jak namalować mamuta”.

In my post about the acorns in archaeology, I said that I could not find any mention of acorns in archaeological material from Ireland and Britain. This makes these two places the only two places in Europe where acorns were not found in archaeological sites. Does this mean that people in Ireland and Britain did not eat acorns when everyone else in the northern hemisphere did? I don’t think so. We know from ethnographic and historical records that people in both countries ate acorns during hard times even in relatively recent times. This means that there is no chance that acorns were not consumed by people in Ireland and Britain during Mesolithic and Neolithic time.

W moim poście o żołędziach w archeologii powiedziałem, że nie znalazłem żadnej wzmianki o żołędziach w materiale archeologicznym z Irlandii i Wielkiej Brytanii. To sprawia, że te dwa miejsca są jedynymi dwoma miejscami w Europie, w których żołędzie nie zostały znalezione na stanowiskach archeologicznych. Czy to oznacza, że ludzie w Irlandii i Wielkiej Brytanii nie jedli żołędzi, tak jak wszyscy inni na półkuli północnej? Nie sądzę. Z zapisów etnograficznych i historycznych wiemy, że ludzie w obu krajach jedli żołędzie w trudnych czasach, nawet stosunkowo niedawo. Oznacza to, że nie ma szans, aby żołędzie nie były spożywane przez ludzi w Irlandii i Wielkiej Brytanii w czasach mezolitu i neolitu.

As I said in my post about how oaks repopulated Europe, oaks reached Eastern Britain by 7500 BC. Oaks reached Ireland very soon afterwards. I believe that oaks were brough into both Britain and Ireland by hunter gatherer groups exploring the western coast of Europe in dugout canoes and I gave detailed explanation why I believe that to be the case in my post „how did oaks repopulated Europe„.

Jak powiedziałem w moim poście o tym, jak dęby ponownie zaludniły Europę, dęby dotarły do wschodniej Wielkiej Brytanii około 7500 pne. Wkrótce potem dąb dotarł do Irlandii. Wierzę, że dęby zostały przywiezione zarówno do Wielkiej Brytanii, jak i Irlandii przez grupy łowców-zbieraczy eksplorujących zachodnie wybrzeże Europy w dłubankach i szczegółowo wyjaśniłem, dlaczego uważam, że tak jest w moim poście „jak dęby ponownie zaludniły Europę”.

We know from the archaeological records that the first humans arrived around 9,000 years ago (7,000 BC). This dating is based on the material recovered from the Mount Sandel Mesolithic site which is the earliest Mesolithic settlement found in Ireland. Storage pits found at the site are of the same basketed dug in storage pits type found in other acorn eating cultures in Evroasia at that time and later. So there is a strong possibility that the Mount Sandel people also ate acorns. At the time when Mount Sandel people lived in Ireland, the island was predominantly covered in a blanket of woodland. Oak and Elm were well established, with Scots Pine growing on the lower slopes of some uplands. There were two major woodland types namely, mature deciduous Oak Woods in the lowlands and valleys with an abundance of ferns, mosses and liverworts, and the Pine Forests on poorer soils with ling heather, grasses and bracken occurring in the ground layer. Some birch woodlands would have also existed on poorer soils. Other species such as Rowan would have flourished in natural openings in the forest canopy, along with whitebeam, holly, ivy and honeysuckle. These forests were home to animals, some of which are extinct in Ireland today, such as brown bear, wolf and boar, while others, such as fox, pine marten and stoat, still occur. The forests covered most of Ireland apart from exposed coastal areas, lake edges and the more exposed mountain tops. Alder and ash were still uncommon in Ireland 8,500 years ago but they expanded to become common around 500 years and 2,000 years later respectively.

Z zapisów archeologicznych wiemy, że pierwsi ludzie przybyli około 9000 lat temu (7000 pne). To datowanie opiera się na materiale odzyskanym z mezolitu Mount Sandel, który jest najwcześniejszą osadą mezolityczną znalezioną w Irlandii. Doły magazynowe znalezione na tym stanowisku są tego samego typu co te które można znaleźć w innych kulturach jedzących żołędzie w Euroazji w tym czasie i później (kosze wykopywane do dołów magazynowych,). Istnieje więc duże prawdopodobieństwo, że ludzie z Mount Sandel również jedli żołędzie. W czasach, gdy w Irlandii mieszkali ludzie z Mount Sandel, wyspa była w większości pokryta lasami. Dąb i Wiąz były dobrze ugruntowane, a sosna zwyczajna rosła na niższych zboczach niektórych wyżyn. Istniały dwa główne typy lasów, a mianowicie dojrzałe dąbrowy liściaste na nizinach i dolinach z dużą ilością paproci, mchów i wątrobowców oraz lasy sosnowe na uboższych glebach z wrzosami, trawami i paprociami występującymi w warstwie poszycia. Niektóre lasy brzozowe istniały również na uboższych glebach. Inne gatunki, takie jak jarzębina, kwitły w naturalnych otworach w baldachimie lasu, razem z mąkinią (jarząbem mącznym – Sorbus aria CB), ostrokrzewem, bluszczem i wiciokrzewem. Lasy te były domem dla zwierząt, z których niektóre wymarły w dzisiejszej Irlandii, takie jak niedźwiedź brunatny, wilk i dzik, podczas gdy inne, takie jak lis, kuna leśna i gronostaj, nadal występują. Lasy pokrywały większość Irlandii, z wyjątkiem odsłoniętych obszarów przybrzeżnych, brzegów jezior i bardziej odsłoniętych szczytów górskich. Olcha i jesion były jeszcze rzadkie w Irlandii 8500 lat temu, ale rozszerzyły się i stały się powszechne odpowiednio około 500 lat i 2000 lat później.

These early inhabitants were Mesolithic hunters, fishers and gatherers. And as we see in all the other major Mesolithic cultures, settled hunter gatherers living in well established mixed oak forests all ate acorns and other nuts as their staple starch food. Why would the Irish Mesolithic hunter gatherers be an exception? Why would they ignore the most abundant and the easiest to get food source which was everywhere around them? Well I don’t think they did. And here is why:

Ci pierwsi mieszkańcy byli mezolitycznymi myśliwymi, rybakami i zbieraczami. I jak widzimy we wszystkich innych głównych kulturach mezolitycznych, osiedleni łowcy-zbieracze żyjący w dobrze ugruntowanych mieszanych lasach dębowych jedli żołędzie i inne orzechy jako podstawowe pożywienie skrobiowe. Dlaczego irlandzcy mezolityczni łowcy-zbieracze mieliby być wyjątkiem? Dlaczego mieliby ignorować najbardziej obfite i najłatwiejsze do zdobycia źródło pożywienia, które było wszędzie wokół nich? Cóż, nie sądzę, żeby to zrobili. A oto dlaczego:

Have a look at these three pictures:

Spójrz na te trzy zdjęcia:

No these are not acorn grinding stones from Native American acorn eating cultures archaeological sites. These are bullaun stones found in Ireland. This is what official archaeology has to say about bullaun stones:

Local folklore often attaches religious or magical significance to bullaun stones, such as the belief that the rainwater collecting in a stone’s hollow has healing properties.Ritual use of some bullaun stones continued well into the Christian period and many are found in association with early churches, such as the ‚Deer’ Stone at Glendalough, County Wicklow. The example at St Brigit’s Stone County Cavan still has its ‚cure’ or ‚curse’ stones. These would be used by turning them whilst praying for or cursing somebody. In May 2012 the first cursing stone to be found in Scotland was discovered on Canna. It has been dated to circa 800. The stones were latterly known as ‚Butterlumps’.St. Aid or Áed mac Bricc was Bishop of Killare in 6th-century. At Saint Aid’s birth his head had hit a stone, leaving a hole in which collected rainwater that cured all ailments, thus identifying it with the Irish tradition of Bullaun stones.Possibly enlarged from already-existing solution-pits caused by rain, bullauns are, of course, reminiscent of the cup-marked stones which occur all over Atlantic Europe, and their significance (if not their precise use) must date from Neolithic times.

Now am i the only one who sees similarity between the acorn grinding stones from North America and bullaun stones? There are thousands of bullaun stones scattered throughout Ireland. If any of them was found in North America, they would have been immediately classified as acorn grinding stones. How is it possible that „we still don’t the precise original use of these stones”? As I said already Ireland was once covered with mighty oak forests and people who lived in these oak forests must have eaten acorns like all the other oak forest dwellers did. And if we find the same type of hollowed stones in Ireland that we find in North America, and if in North America these stones were used for grinding acorns, then these Irish stones must have been used for the same purpose.

Czy tylko ja dostrzegam podobieństwo między kamieniami do mielenia żołędzi z Ameryki Północnej a kamieniami typu bullaun? W całej Irlandii rozrzucone są tysiące kamieni typu bullaun. Gdyby którykolwiek z nich został znaleziony w Ameryce Północnej, natychmiast zostałby sklasyfikowany jako kamień do mielenia żołędzi. Jak to możliwe, że „wciąż nie znamy dokładnego pierwotnego zastosowania tych kamieni”? Jak już powiedziałem, Irlandia była kiedyś pokryta potężnymi lasami dębowymi, a ludzie, którzy żyli w tych dębowych lasach, musieli jeść żołędzie, tak jak wszyscy inni mieszkańcy dębowych lasów. A jeśli w Irlandii znajdziemy ten sam rodzaj wydrążonych kamieni, które znajdujemy w Ameryce Północnej, i jeśli w Ameryce Północnej kamienie te były używane do mielenia żołędzi, to te irlandzkie kamienie musiały być chyba używane do tego samego celu.

I believe that bullaun stones were not classified as acorn grinding stones primarily because until very recently we did not realise how ubiquitous consumption of acorns was in the northern hemisphere. Maybe its time to re-evaluate the bullaun stones and reclassify them as acorn grinding stones. I also believe that the earliest examples of bullaun stones probably date to Mesolithic and Neolithic time and that they predate the arrival of agriculture to Ireland..

Uważam, że kamieni typu bullaun nie zaliczano do kamieni do mielenia żołędzi przede wszystkim dlatego, że do niedawna nie zdawaliśmy sobie sprawy z tego, jak wszechobecne było spożywanie żołędzi na półkuli północnej. Może nadszedł czas, aby ponownie ocenić kamienie bullaun i przeklasyfikować je jako kamienie do mielenia żołędzi. Wierzę również, że najwcześniejsze przykłady kamieni typu bullaun pochodzą prawdopodobnie z mezolitu i neolitu oraz że powstały przed przybyciem rolnictwa do Irlandii.

As you could see from the pictures of grinding stones from North America, people used both cup, conical and saddle grinding stones originally for grinding acorns and then later for grinding grains. Apart from bullaun (conical) grinding stones, in Ireland we also find saddle grinding stones.

Jak widać na zdjęciach kamieni szlifierskich z Ameryki Północnej, ludzie używali zarówno garnkowych, stożkowych, jak i siodłowych kamieni szlifierskich pierwotnie do mielenia żołędzi, a później do mielenia zbóż. Oprócz kamieni szlifierskich bullaun (stożkowych) w Irlandii spotykamy również kamienie szlifierskie siodłowe.

This is a saddle grinding stone from the bronze age ~1500-500BC from Ovidstown, County Kildare.

To siodłowy kamień do szlifowania z epoki brązu ~ 1500-500 pne z Ovidstown w hrabstwie Kildare.

This is a saddle grinding stone from the bronze age from Grange county Meath.

To siodłowy kamień do szlifowania z epoki brązu z hrabstwa Grange Meath.

Saddle querns were used into the 20th century in Ireland, as you can see on this picture kept in the Ulster Folk and Transport museum. Compare this picture with the picture of the old Native American woman grinding acorns using saddle grinding stone. I love this woman’s face. She looks more Native American than the actual Native American woman on the above picture.

Żarna siodłowe były używane w Irlandii w XX wieku, jak widać na tym obrazie przechowywanym w muzeum Ulster Folk and Transport. Porównaj to zdjęcie ze zdjęciem starej rdzennej Amerykanki szlifującej żołędzie za pomocą siodłowego kamienia do szlifowania. Uwielbiam twarz tej kobiety. Wygląda bardziej na rdzenną Amerykankę niż rzeczywista rdzenna Amerykanka na powyższym zdjęciu.

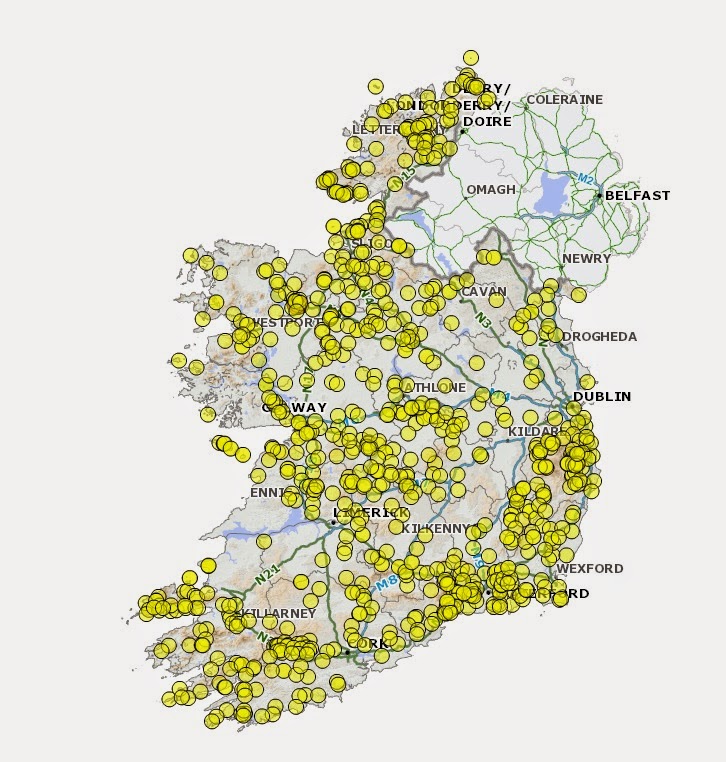

This is a list of all the Irish bullaun stones as recorded in the National monument service database. As you can see they are found all over Ireland in huge numbers.

To jest lista wszystkich irlandzkich kamieni bullaun zarejestrowanych w bazie danych National Monument Service. Jak widać, występują w całej Irlandii w ogromnych ilościach.

Ireland is not the only place in Europe where we find bullaun stones. As far as I know they are also found in Cornwall, France, on the Swedish island of Gotland, Lithuania, Germany, Belorussia…I was recently made aware of the existence of many bullaun type grinding slabs in the Levant of which the earliest were dated to 11,000 BC. I am preparing an article about these grinding stones and will publish it as soon as it’s finished.

Irlandia nie jest jedynym miejscem w Europie, gdzie znajdujemy kamienie bullaun. O ile mi wiadomo, można je również znaleźć w Kornwalii we Francji, na szwedzkiej wyspie Gotlandia, na Litwie, w Niemczech, na Białorusi… Niedawno dowiedziałem się o istnieniu wielu płyt szlifierskich typu bullaun w Lewancie, z których najwcześniejsze były datowane na 11 000 pne. Przygotowuję artykuł o tych kamieniach szlifierskich i opublikuję go, gdy tylko będzie gotowy.

These are grinding stones found in so called „court houses” in Cornwall.

Są to kamienie szlifierskie znalezione w tzw. „domach sądowych” w Kornwalii.

These are grinding stones from Cornwall dated to late Neolithic early Bronze Age.

This is one of many old hollowed stones from the Baltic. They are called bowl stones and are, like in Ireland and in Slavic countries, regarded as sacred. The place where the stone is located is used as a place of worship. The diameter of this stone is about 60 cm and a depth – about 15 cm. In the past people considered the accumulated water as sacred and thought that it had healing properties. In the past the stone used to be called the stone of god.

To jeden z wielu starych wydrążonych kamieni znad Bałtyku. Nazywane są kamiennymi misami i są, podobnie jak w Irlandii i krajach słowiańskich, uważane za święte. Miejsce, w którym znajduje się kamień, służy jako miejsce kultu. Średnica tego kamienia wynosi około 60 cm, a głębokość około 15 cm. W przeszłości ludzie uważali zgromadzoną wodę za świętą i uważali, że ma ona właściwości lecznicze. W przeszłości kamień ten nazywano kamieniem boga.

You can see many more of these stones if you run this search. Here are some of them. This one is called „Lielais Daviņu Akmens” which means great stone of giving, offering, great altar. It seems that the stone was linked to harvest rituals.

Możesz zobaczyć o wiele więcej tych kamieni, jeśli uruchomisz to wyszukiwanie. Tutaj jest kilka z nich. Ten nazywa się „Lielais Daviņu Akmens”, co oznacza wielki kamień dawania, ofiarowania, wielki ołtarz. Wydaje się, że kamień był powiązany z rytuałami żniwnymi.

This stone stands on a hill, where an old oak forest grew until the seventeenth century. The hill was a site of a pagan temple.

Kamień ten stoi na wzgórzu, na którym do XVII wieku rósł stary las dębowy. Na wzgórzu znajdowała się pogańska świątynia.

For information about these stones in English look at the pages 27 – 33 of the book „Studies into the Balts’ Sacred Places„.

Informacje o tych kamieniach w języku angielskim można znaleźć na stronach 27 – 33 książki „Studies into the Balts’ Sacred Places”.

I was just made aware of an article about an interesting half-made bowl-stone from Baltic region. On its top part there’s a circular groove of a similar size as the usual bowls on other stones, as if someone had intended to gouge out a bowl there too but stopped half way through the process of gouging the hole.

Właśnie dowiedziałem się w artykule o ciekawym półfabrykacie z misy z regionu bałtyckiego. Na jego górnej części znajduje się koliste wyżłobienie podobnej wielkości jak zwykłe miseczki na innych kamieniach, jakby ktoś tam też chciał wyżłobić miskę, ale zatrzymał się w połowie procesu żłobienia otworu.

We can deduce though that this is how these bowl stones were actually made from their name in Lithuanian. Lithuanian word for bowl is dubuo, dubeni akameni…These words come from Slavic root dub meaning wood but also to gouge. This second meaning comes from the time when utensils were made by gouging bowl like holes in pieces of wood and later stone. In Southern Slavic languages Dubiti means to gouge and Dubeni, Dubeno means gouged, with a gouged hole, bowl in it…Dubeni kameni in South Slavic languages means gouged stones, bowl stones…

Możemy jednak wywnioskować, że właśnie w ten sposób powstały te kamienie misowe, od ich nazwy w języku litewskim. Litewskie słowo oznaczające miskę to dubuo, dubeni akameni… Te słowa pochodzą od słowiańskiego rdzenia dub oznaczającego drewno, ale także żłobienie. To drugie znaczenie pochodzi z czasów, gdy naczynia robiono przez żłobienie misek jak dziur w kawałkach drewna, a później w kamieniu. W językach południowosłowiańskich Dubiti oznacza wyżłobić, a Dubeni, Dubeno oznacza wyżłobiony, z wyżłobioną dziurą, w środku miskę… Dubeni kameni w językach południowosłowiańskich oznacza wyżłobione kamienie, kamienie miskowe…

This is an example of the „pierres à cupules” or cupped stone from france. This is a communal boulder grinding stone.

To jest przykład „pierres à cupules” lub kamienia miseczkowego z Francji. Jest to gminny kamień do szlifowania głazów.

This is a bullaun stone from Leistruper forest Westphalia Germany (taken by Oliver Reichelt).

To jest kamień bullaun z lasu Leistruper w Westfalii w Niemczech (zdjęcie Olivera Reichelta).

These are just two of many bullaun stones from Belorussia. In Belorussia these stones are also regarded as sacred and the water accumulated in them is considered to have healing properties. In Belorussian these hollowed stones are called „valun” which in Slavic languages means both a boulder and a grinding stone. I believe that this name holds the key for understanding the original purpose of these stones and proves how ancient they truly are. But I will talk about this in one of my next posts….

These are just two of many bullaun stones from Belorussia. In Belorussia these stones are also regarded as sacred and the water accumulated in them is considered to have healing properties. In Belorussian these hollowed stones are called „valun” which in Slavic languages means both a boulder and a grinding stone. I believe that this name holds the key for understanding the original purpose of these stones and proves how ancient they truly are. But I will talk about this in one of my next posts….To tylko dwa z wielu kamieni typu bullaun z Białorusi. Na Białorusi kamienie te są również uważane za święte, a zgromadzona w nich woda ma właściwości lecznicze. Po białorusku te wydrążone kamienie nazywane są „valun”, co w językach słowiańskich oznacza zarówno głaz, jak i kamień szlifierski. Wierzę, że ta nazwa zawiera klucz do zrozumienia pierwotnego przeznaczenia tych kamieni i dowodzi, jak bardzo są stare. Ale o tym opowiem w jednym z kolejnych postów….

Bullaun stone , situated on the location of a destroyed ancient chapel.

Izhorian Plateau, St. Petersburg region, NW Russia.

Kamień Bullaun, położony na miejscu zniszczonej starożytnej kaplicy. Płaskowyż Izhorian, obwód petersburski, północno-zachodnia Rosja.

This is duben kamen, well, called zdenac from Dinara mountain region in Croatia:

To jest duben kamen, no cóż, zwany zdenac z regionu gór Dynarskich w Chorwacji:

This is a picture of the central hole with the reflection of the mountain top:

To jest zdjęcie centralnego otworu z odbiciem szczytu góry:

Bullaun stones Serbia. Unfortunately I don’t know exact location…I also have information about similar stones in Makedonia.

Kamień Bullaun – Serbia. Niestety nie znam dokładnej lokalizacji… Mam też informacje o podobnych kamieniach w Macedonii.

If anyone has any examples of similar stones from Europe please let me know and send me a link to the pictures so that I can update the post to keep it relevant.

Jeśli ktoś ma jakieś przykłady podobnych kamieni z Europy, proszę dać mi znać i przesłać mi link do zdjęć, abym mógł zaktualizować post, aby był aktualny.

In the end there is something I would like to draw your attention to.

Na koniec chciałbym zwrócić waszą uwagę na coś.

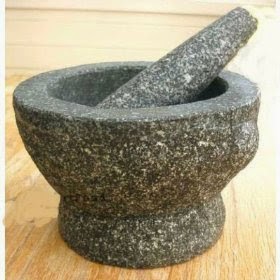

This is a prehistoric bullaun stone mortar and pestle:

And here is how it must have been used to grind Acorns:

A oto jak musiał być używany do mielenia żołędzi:

And here is a bullaun stone mortar and pestle I have in my kitchen:

A oto kamienny moździerz i tłuczek typu bullaun, który mam w kuchni:

I hope you had fun reading this post. If you did, please plus it. It would mean a lot to me. Thank you and stay happy.

A bullaun (Irish: bullán; from a word cognate with „bowl” and French bol) is the term used for the depression in a stone which is often water filled. Natural rounded boulders or pebbles may sit in the bullaun.[1] The size of the bullaun is highly variable and these hemispherical cups hollowed out of a rock may come as singles or multiples with the same rock.[2][3]

Local folklore often attaches religious or magical significance to bullaun stones, such as the belief that the rainwater collecting in a stone’s hollow has healing properties.[4] Ritual use of some bullaun stones continued well into the Christian period and many are found in association with early churches, such as the ‚Deer’ Stone at Glendalough, County Wicklow.[5] The example at St Brigit’s Stone, County Cavan, still has its ‚cure’ or ‚curse’ stones. These would be used by turning them whilst praying for or cursing somebody.[1] In May 2012 the second cursing stone to be found in Scotland was discovered on Canna and drawn soon after by archaeological illustrator Thomas Small.[6] It has been dated to c. 800.[7] The first was found on the Shiant Islands.[8] It has been dated to c. 800.[7] The stones were latterly known as ‚Butterlumps’.[9]

St. Aid or Áed mac Bricc was Bishop of Killare in 6th-century. At Saint Aid’s birth his head had hit a stone, leaving a hole in which collected rainwater that cured all ailments, thus identifying it with the Irish tradition of Bullaun stones.[10]

Bullauns are not unique to Ireland and Scotland, being also found on the Swedish island of Gotland, Lithuania and France. ‚King Arthur’s footprint’ at Tintagel Castle, Cornwall, among other circular depressions at prehistoric ritual sites in Devon & Cornwall, was previously associated with kingship rituals.[11] Possibly enlarged from already-existing solution-pits caused by rain, bullauns are reminiscent of the cup-marked stones which occur all over Atlantic Europe, and their significance (if not their precise use) must date from Neolithic times.[2]

Rosewall Hill near St Ives in Cornwall UK has several bullaun which can be found on top, or near the tops of the granite outcrops or cairns on high points on the hill. It is open to question as to whether or not these are man-made or formed by the natural erosion of the granite. Many of the granite boulders on this hill have what appear to be erosion formed concavities, usually pear shaped, which indicate bullaun in formation. However, the location of the larger forms on the tops of the outcrops does suggest that these sites have been chosen. Trevalgan Hill, just to the north of Rosewall Hill, has a round bullaun some 50 cm across as can be seen in the photograph.