Goran Pavlovic – Wren or wran?

„…if it call from behind you importuning of your wife by another man in despite of you. If it be on the ground behind you, your wife will be taken from you by force. If the wren call from the east, poets are coming towards you, or tidings from them. If it call behind you from the south, you will see the heads of good clergy or hear death tidings of noble ex lay men. If it call from the south robbers and evilkinsmen are coming. If it call from the north west, a noble hero of good lineage and noble hospitallars and goodwomen are coming.

If it call from the north, bad people are coming whether warriors or clerics or bad women and wiched youths are on way…”

♦

„… jeśli zza ciebie woła, twoja żona będzie nagabywana przez innego mężczyznę. Jeśli będzie na ziemi za tobą, twoja żona zostanie ci siłą zabrana. Jeśli strzyżyk zawoła ze wschodu, poeci zbliżają się do ciebie, lub wieści od nich. Jeśli woła za tobą z południa, zobaczysz głowy sługów bożych albo dowiesz się o śmierci kogoś szlachetnego. Jeśli odezwie się z południa wezwie zbójców i złoczyńców. Gdy woła z północnego zachodu, nadchodzi szlachetny bohater z dobrego rodu, szlachetny zakonnik i dobra kobieta. Jeśli woła z północy, nadchodzą źli ludzie, czy to wojownicy, czy duchowni, czy złe kobiety i zła młodzież, którzy staną ci na drodze … ”

The house that is least generous is likely to have the wren buried under their door, „through which no luck would then enter for a twelvemonth”.

♦

W domu, który jest najmniej szczodry, najprawdopodobniej zostanie pochowany strzyżyk pod drzwiami, „przez które nie trafił wtedy szczęście przez dwanaście miesięcy”.

♦

[Jak widać nawet w irlandii stosunek do strzyżyka jest dwoisty, co sugeruje że Strzyżyk – Królik będący Królem Małych Ptaków, jest ptakiem Bogów Losu – czyli Koszu – Mokoszów, a jak się przekonamy jest to ptaszek który oszukał lods podejmując walkę z prawdziwym królem ptakó – Orłem. CB]

♦

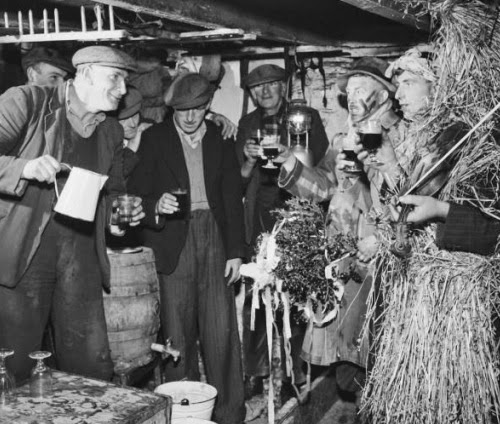

Here are some pictures of „wren boys” or „straw boys” from Ireland:

♦

Oto kilka zdjęć „strzyżyków” lub „słomianych chłopców” z Irlandii:

A group of mummers in Ireland celebrate St Stephen’s Day or ‚Wren’s Day’ on 26th December by processing from house to house with their instruments, circa 1955. (Photo by George Pickow/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

This fable is already known to Aristotle (Historia Animalium 9.11) Plutarch (Political Precepts xii.806e) and Pliny (Naturalis Historia 10.74).

Plutarch implied that this story teaches us that cleverness, trickery is better than strength. Hmmmm…Great lesson….

What is interesting is that this old fable is actually still told as a fairy-tale in Ireland and in Slavic lands.

Ta bajka jest już znana Arystotelesowi (Historia Animalium 9.11) Plutarchowi (Zasady polityczne xii.806e) i Pliniuszowi (Naturalis Historia 10.74). Plutarch zasugerował, że ta historia uczy nas, że spryt, oszustwo jest lepsze niż siła. Hmmmm … Świetna lekcja … Co ciekawe, w Irlandii i na ziemiach słowiańskich ta stara bajka jest nadal opowiadana jako ważne podanie.

In Irish version, god wished to know who was the king of all birds so he set a challenge. The bird who flew highest and furthest would win. The birds all began together but they dropped out one by one until none were left but the great eagle. The eagle eventually grew tired and began to drop lower in the sky. At this point, the treacherous wren emerged from beneath the eagle’s wing to soar higher and further than all the others. And this is why wren is hunted and killed. In Irish the word Dreoilín means wren and the word dreolán means trickster…

W wersji irlandzkiej bóg chciał wiedzieć, kto jest królem wszystkich ptaków, więc rzucił wyzwanie. Ptak, który poleciałby najwyżej i najdalej, wygrałby. Wszystkie ptaki zaczęły razem, ale odpadały jeden po drugim, aż nie pozostał żaden oprócz wielkiego orła. W końcu orzeł zmęczył się i zaczął opadać niżej na niebie. W tym momencie zdradziecki strzyżyk wynurzył się spod skrzydła orła i wzbił się wyżej i dalej niż wszystkie inne. I dlatego strzyżyk jest ścigany i zabijany. W języku irlandzkim słowo Dreoilín oznacza strzyżyk, a słowo dreolán oznacza oszusta …

In the Slavic version the bird which flies the highest, while carrying the wren hidden in his feathers, is eagle (in East Ukrainian and Polish version) or heron (in West Ukrainian version) or stork (in Sorbian version). Once the eagle (heron, stork) out-flies all the other birds, wren flies out of its plumage and out-flies the eagle (heron, stork).

W wersji słowiańskiej ptakiem, który leci najwyżej, niosąc strzyżyka ukrytego w piórach, jest orzeł (w wersji wschodnio-ukraińskiej i polskiej) lub czapla (w wersji zachodnio-ukraińskiej) lub bocian (w wersji łużyckiej). Gdy orzeł (czapla, bocian) odlatuje od wszystkich innych ptaków, strzyżyk wylatuje z upierzenia i leci wyżej od orła (czapli, bociana).

That wren is seen as trickster in Slavic mythology can be seen from the fact that wren is also known as „obluda” meaning „trickster”, „durisvit” meaning „charlatan, fool”, „zvoditelj” meaning „joker”. But in Slavic version of the story, the trick is discovered and wren is forced to run and hide in order to avoid punishment. In Ukrainian and Sorbian versions of the story, this is not the end. Angry birds decide that because they could not find the king of the bird through a „who can fly the highest” competition decide to stage a context in „who can get the deepest”. The bird that can get the deepest into the ground will be the king of the birds. And again wren won the contest. The wren scientific name Troglodytidae is derived from the word „troglodyte”, which means „cave-dweller”. The wrens get their scientific name from the fact that they forage in dark crevices and hide from the cold in holes just like mice. This small, brown bird that scurries through the undergrowth and into log piles and holes in search of insects and any other small animals, particularly beetles and spiders, from a distance actually looks like a mouse. Thus in Ukrainian and Polish tradition, wren is also known as mouse king. It is interesting that Icelanders also consider wren to be the „mouse’s brother”.

The Celts and the Slavs seem to have understood the story slightly differently from the Greeks. Wren’s trickery was not seen as virtue but as a crime, a sin…punishable by death…

Wydaje się, że Celtowie i Słowianie rozumieli tę historię nieco inaczej niż Grecy. Oszustwo Wrena nie było postrzegane jako cnota, ale jako zbrodnia, grzech … karany śmiercią …

Are Slavic wren stories versions of older Celtic stories preserved in Central Europe when Celts morphed into Slavs? Or does this story about the cheating wren predate both Celts and Slavs? Or is this story about the cheating wren a later corruption of a much earlier story which doesn’t involve wren at all but another bird whose name sounds very much like wren, making the wren an unfortunate victim of a mistaken identity?

Czy historie słowiańskie o strzyżykach są wersjami starszych opowieści celtyckich jaki zachowały się w Europie Środkowej, kiedy Celtowie przekształcili się w Słowian? A może ta opowieść o oszuście strzyżyku jest starsza od Celtów i Słowian? A może ta historia o oszukującym strzyżyku jest późniejszym zepsuciem znacznie wcześniejszej historii, która wcale nie dotyczy strzyżyka, ale innego ptaka, którego imię brzmi bardzopodobnie jak strzyżyk, co czyni go nieszczęśliwą ofiarą błędnej tożsamości?

Let’s see what we can dig out.

Remember that wren forages and hides in holes in the ground, in „the underworld”. This makes wren, the bird that can be under ground, on the ground and in the air „the bird that connects the three worlds”.

As I already said, wren is the first bird to start singing in the morning. And the loudest. This is why wren is known as the herald of the rising sun.

Zobaczmy, co uda nam się wykopać. Pamiętaj, że strzyżyk żeruje i chowa się w dziurach w ziemi, w „podziemiach”. To sprawia, że strzyżyk, ptak, który może znajdować się pod ziemią, na ziemi i w powietrzu, jest „ptakiem łączącym trzy światy”. Jak już powiedziałem, strzyżyk jest pierwszym ptakiem, który rano zaczyna śpiewać. I to najgłośniej. Dlatego strzyżyk jest znany jako zwiastun wschodzącego słońca.

So every evening both the sun and wren go underground. And every morning wren emerges from the underground before the sun does, effectively out-running the sun during their race from the underworld to heaven. Now the bird most associated with the sun is eagle, who is the solar bird pretty much in every religion in the northern hemisphere. So wren racing the sun can be nicely represented with wren racing an eagle. Is this the origin of the story about the bird race in which a wren beat an eagle?

Więc każdego wieczoru zarówno słońce, jak i strzyżyk schodzą pod ziemię. I każdego ranka strzyżyk wyłania się z podziemia, zanim zrobi to słońce, skutecznie wyprzedzając słońce podczas ich wyścigu z podziemi do nieba. Obecnie ptakiem najbardziej kojarzonym ze słońcem jest orzeł, który jest ptakiem słonecznym praktycznie we wszystkich religiach na półkuli północnej. Więc strzyżyk ścigający się ze słońcem może być ładnie przedstawiony jako strzyżyk ścigający się z orłem. Czy to jest początek opowieści o wyścigu ptaków, w którym strzyżyk pobił orła?

Also because wren announces the arrival of the sun, during the Pagan times, wren, the „little king of birds”, was announcing the arrival of the Sun, the „big king of heaven”. That is a particularly important role in sun worshiping religions. No wonder wren was so venerated and protected.

Również dlatego, że strzyżyk zapowiada nadejście słońca, w czasach pogańskich strzyżyk, „mały król ptaków”, zapowiadał nadejście Słońca, „wielkiego króla niebios”. Jest to szczególnie ważna rola w religiach czczących słońce. Nic dziwnego, że strzyżyk był tak czczony i chroniony. [Jest zwiastunem, posłańcem, który zwiastuje Słońce czyli byłby to ptak Weniów-Podagów – Boskich Posłańców, Opiekunów Ptaków, Władców Podróży, w tym przelotów, ale i żeglugi wodnej, morskiej i opiekunami wędrowców, także Opiekunami Drogi Życiowej Człowieka. CB]

European Wrens are migratory in some parts of Europe, flying anything up to 2500 km (1500 miles) with some migrating all the way from Scandinavia down to Spain. But in British Isles wren is one of the few non migratory songbirds and is often the only bird singing during the winter solstice period. Its song on the Winter Solstice morning, not only announces the sunrise, it announces the beginning of the new solar year, the birth of the new sun, new sun god, new little king of heaven.

Europejskie strzyżyki migrują w niektórych częściach Europy, latając do 2500 km (1500 mil), a niektóre migrują aż ze Skandynawii do Hiszpanii. Ale na Wyspach Brytyjskich strzyżyk jest jednym z niewielu niemigrujących ptaków śpiewających i często jest jedynym ptakiem śpiewającym podczas przesilenia zimowego. Jego piosenka w poranek przesilenia zimowego nie tylko zapowiada wschód słońca, ale także początek nowego roku słonecznego, narodzin nowego słońca, nowego boga słońca, nowego małego króla nieba.

Christmas is repackaged Winter Solstice and that many old rituals related to winter solstice were moved to Christmas. So instead of the birth of the new sun, new sun god, little king of heaven which happens on the Winter Solstice morning, we have the birth of baby Jesus, the son of God the king of heaven, which happens on Christmas morning. Now correct me if I am wrong, but the son of the „king of heaven” is defacto the „prince of heaven” or the „little king of heaven”. Right?

Boże Narodzenie jest przepakowanym Przesileniem Zimowym, wiele starszymi rytuałami związanymi z przesileniem zimowym, które zostały przeniesione na Boże Narodzenie. Więc zamiast narodzin nowego słońca, nowego boga słońca, małego króla niebios, które zdarzają się w poranek przesilenia zimowego, mamy narodziny małego Jezusa, syna Bożego, króla niebios, co ma miejsce w Boże Narodzenie rano. Teraz popraw mnie, jeśli się mylę, ale syn „króla niebios” jest de facto „księciem nieba” lub „małym królem nieba”. W porządku?

When the Winter Solstice celebration of the birth of new Sun God was replaced by the Christmas celebration of the birth of the Son of God, Christians didn’t want to be reminded of the old Sun God by the wren, who was still announcing his arrival. So Is this why wren had to die on the day the new Son of God was born to replace Sun the God? Look at the day on which the dead wren, the dead herald of the old Sun God was paraded around. That day is the day after the Christmas day, the St Stephen’s day. Now who is this St Stephen? St Stephen or St Stephan is traditionally venerated as the Protomartyr or first martyr of Christianity. Now this means the first one to be killed in the name of Christ, Son of God. And the first to be killed in the name of the Son of God is Sun the God. New young Sun God, old „little king of heaven”, which used to be born on the day of the Winter Solstice is now killed on Christmas day, replacement for the Winter Solstice, and is replaced by Son of God, new „little king of heaven”. And the day when this „first victim of Christianity” is celebrated is St Stephen’s day. Funnily name Stephen or Stephan was originally a title meaning „crowned” or king, the origin of which is in the Ancient Greek word „στέφανος” which means crown. It was the title given to many kings in medieval Serbia, Croatia, Hungary and Poland. So the death of the old „little king” and the enthronement of the new „little king” is celebrated on the day of Stephen, the day of the „crowned one” the day of the king. Do you think that there is some kind of symbolism here?

Kiedy zimowe przesilenie, święto narodzin nowego Boga Słońca zostało zastąpione bożonarodzeniowymi obchodami narodzin Syna Bożego, chrześcijanie nie chcieli, aby przypominał im starego Boga Słońce, który wciąż przez strzyżyka zapowiada swoje przybycie . Czy to dlatego strzyżyk musiał umrzeć w dniu, w którym narodził się nowy Syn Boży, aby zastąpić dawnego Boga? Spójrz na dzień, w którym paradowano z martwym strzyżykiem, martwym heroldem starego Boga Słońca. Ten dzień jest dniem po Bożym Narodzeniu, dniem św. Szczepana. Kim jest ten St Stephen? St Stephen lub św. Szczepan jest tradycyjnie czczony jako Protomęczennik lub pierwszy męczennik chrześcijaństwa. To oznacza, że pierwszy zostanie zabity w imię Chrystusa, Syna Bożego. A więc pierwszym zabitym w imię Syna Bożego jest Bóg Słońce. Nowy młody Bóg Słońca, stary „mały król nieba”, który urodził się w dniu przesilenia zimowego, teraz zostaje zabity w Boże Narodzenie, zastępując przesilenie zimowe, i zostaje zastąpiony przez Syna Bożego, nowego „małego króla” nieba ”. A dzień, w którym świętuje się tę „pierwszą ofiarę chrześcijaństwa”, to dzień św. Szczepana. Zabawne imię Stephen lub Stephan było pierwotnie tytułem oznaczającym „koronowany” lub król, którego znaczenie pochodzi ze starożytnego greckiego słowa „στέφανος”, które oznacza koronę. Był to tytuł nadany wielu królom średniowiecznej Serbii, Chorwacji, Węgier i Polski. Tak więc śmierć starego „małego króla” i intronizacja nowego „małego króla” obchodzona jest w dniu Szczepana, w dniu „koronowanego”, w dniu króla. Czy myślisz, że jest tu jakaś symbolika?

But this is not all.

Why is the killing of wrens or disturbing of their nests punished by thunder? And why is it said that wren is the bird of Lugh, the Celtic thunder god? Well to understand this we need to look at what happens to the newly born Sun God after the Winter Solstice.

Remember my post „Two crosses„?

Ale to nie wszystko. Dlaczego zabijanie strzyżyków lub naruszanie ich gniazd jest karane piorunami? Dlaczego mówi się, że strzyżyk jest ptakiem Lugha, celtyckiego boga piorunów? Aby to zrozumieć, musimy przyjrzeć się, co dzieje się z nowo narodzonym Bogiem Słońca po przesileniu zimowym. Pamiętasz mój post „Dwa krzyże”?

As soon as he is born on Winter Solstice, the Sun God starts its ascend to the throne. He finally sits on its throne on Summer Solstice. This is the day when the sun reaches the highest point in the sky above the northern hemisphere. This is the maximum sunlight day. One would expect that the day after the Summer solstice, as the days start getting shorter the weather would start getting colder. But that is not the case. The days start getting shorter but the weather continues to get warmer. Until the 2nd of August. This is the maximum heat day. This is the sun at its maximum strength. After that the days finally start getting cooler.

In Serbia the 2nd of August is Perun day, but also the day of Ilija Gromovnik, the Thundering Sun, the Thunder Giant. In Serbian Thunder Giant is Grom Div. In Ireland 2nd of August is the day of Chrom Dubh, the Sky God and the main agricultural deity of the old Ireland. But also the day of Lugh, the thunder god.

Now if we look at wren life-cycle we will notice something very interesting. This is an excerpt from Edward Armstrong’s THE WREN (1955) which talks about wren’s singing patterns:

W Serbii 2 sierpnia to dzień Peruna, ale także dzień Iliji Gromovnika, Grzmocącego Słońca, Grzmotowego Olbrzyma. W języku serbskim Thunder Giant to Grom Div. W Irlandii 2 sierpnia jest dniem Chrom Dubh, Boga Nieba i głównego bóstwa rolniczego dawnej Irlandii. Ale także dzień Lugha, boga piorunów. Teraz, jeśli spojrzymy na cykl życia strzyżyka, zauważymy coś bardzo interesującego. Oto fragment z THE WREN Edwarda Armstronga (1955), który mówi o wzorach śpiewu strzyżyka:

„Usually there is little song in January apart from imperfect phrases, lacking in verve, during the day, especially in the morning if the weather is mild, and some rallying songs at dusk, if it is severe. …. Favourable weather in February elicits a fair amount of morning song, a song or two in the afternoon and a little regular song before roosting. … In March [if the weather is mild] there is intermittent singing for two or three hours in the morning, an increase in the evening output and a general advance towards day-long song .. at the end of the month, when nest-building has begun, song is in every way well developed. … In April there is still more territorial song … apparently there is some diminution in May [when females are incubating or, towards end of May, feeding young] … it is difficult accurately to assess the output of song at this stage as individuals vary according to the phase of the breeding cycle. … In June many reach their highest daily production of song and a few young Wrens begin to sing at the end of the month. During July song decreases and deteriorates, and some adults go almost out of song, but the number of juveniles singing increases. The moult in August is accompanied by an abrupt diminution of song, so far as most adults are concerned, but the birds of the year frequently utter their broken ditties, mainly during the hour and a half after sunrise. This may continue until about the beginning of October when song becomes bolder and clearer, though still incomplete. In November if the weather is [mild], there is little change: Wrens are heard for about half and hour after sunrise and a few phrases are uttered in the late afternoon and towards sunset. Song diminishes in December, but even when it is freezing Wrens occasionally engage in song duels.”

So wrens sing the most around Summer Solstice period as befits the herald of the Sun. But they get almost completely silent around Crom Dubh, Lugh, Ilija Gromovnik, Perun day. And this is the only time when these loudmouths shut up. Why? The reason for the sudden silence of wrens, is the annual moult: a complete change of feathers after the final wear and tear of the breeding season. Even juveniles are changing into adult plumage. Moulting takes energy, as the bird’s metabolism speeds up to grow new feathers and push out the old ones. The birds become lethargic, reluctant to fly very far, and spend much of the day resting in deep cover. Keeping their beaks shut.

Tak więc strzyżyki śpiewają najwięcej w okresie przesilenia letniego, jak przystało na zwiastunów Słońca. Ale prawie całkowicie milczą wokół Crom Dubh, Lugh, Ilija Gromovnik, Perun. I to jest jedyny raz, kiedy te gadulce się zamykają. Czemu? Przyczyną nagłego milczenia strzyżyków jest coroczne pierzenie: całkowita zmiana upierzenia po ostatnim zużyciu w sezonie lęgowym. Nawet młode osobniki zmieniają upierzenie na dorosłe. Pierzenie wymaga energii, ponieważ metabolizm ptaka przyspiesza, aby wyhodować nowe pióra i wypchnąć stare. Ptaki stają się ospałe, niechętnie latają bardzo daleko i spędzają większość dnia odpoczywając w głębokiej kryjówce. Trzymają dzioby zamknięte.

And this coincides with the period when Summer turns into Autumn and the beginning of the harvest. For early farmers this must have been very auspicious. As I wrote in my post about the Sky Father, the beginning of the harvest is the most critical period of the whole grain vegetative cycle. Sudden storm, heavy rain and particularly strong winds can destroy everything farmers worked for the whole year. On Summer Solstice Sun God was powerful and merciful. On the 2nd of August he is even more powerful but he is angry, angry because his reign is coming to an end. This is why 2nd of August is the real seat of the Sky God. Because this is when he is most dangerous.

A to zbiega się z okresem, kiedy lato zamienia się w jesień i początek żniw. Dla pierwszych rolników musiało to być bardzo pomyślne. Jak pisałem w swoim poście o Sky Father, początek żniw to najbardziej krytyczny okres w cyklu wegetacyjnym pełnego ziarna. Nagła burza, ulewne deszcze i szczególnie silne wiatry mogą zniszczyć wszystko, co rolnicy pracowali przez cały rok. Podczas letniego przesilenia słońce Bóg był potężny i miłosierny. 2 sierpnia jest jeszcze potężniejszy, ale zły, zły, bo jego panowanie dobiega końca. Dlatego 2 sierpnia jest prawdziwą siedzibą Boga Nieba. Ponieważ właśnie wtedy jest najbardziej niebezpieczny.

And in Serbia, on the 2nd of August people celebrate St Stephen the Wind maker. This saint is Christianized version of Stribog, the old Slavic wind god, the destructive face of Perun.

A w Serbii 2 sierpnia świętuje się św. Szczepana, twórcę wiatru. Ten święty jest schrystianizowaną wersją Striboga, starego słowiańskiego boga wiatru, niszczycielskiej twarzy Peruna.

So during this „dangerous” harvest period, during the reign of Perun the destroyer, Stribog, wren doesn’t sing. It hides and it looks like it has disappeared. Well this looks like a fitting announcement of the arrival of the old cranky god, don’t you think? Run and hide… And then it starts singing again when the harvest is finished and the reign of the sun is over. Right on time for the arrival of the Lady, Virgo. Is this why there is the link between the Storm god and wren and why those who harm wrens are punished by thunder? I also believe that the fact that wren is in Slavic countries also known as „bull’s eye” is another thing that confirms this link between the Sky god in his terrible Destroyer role and wren. The sacrificial animal of both Perun and Crom Dubh was bull…

Tak więc w tym „niebezpiecznym” okresie żniw, za panowania niszczyciela Peruna, Striboga, strzyżyk nie śpiewa. Ukrywa się i wygląda na to, że zniknął. Cóż, to wygląda na stosowną zapowiedź nadejścia starego zepsutego boga, nie sądzisz? Uciekaj i chowaj się … A potem znowu zaczyna śpiewać, gdy skończą się żniwa i skończy się panowanie słońca. Punktualnie na przybycie Pani, Panny. Czy to dlatego istnieje powiązanie między bogiem burzy a strzyżykiem i dlaczego ci, którzy krzywdzą strzyżyki, są karani piorunami? Uważam też, że fakt, że strzyżyk jest w krajach słowiańskich znany również jako „oko byka”, to kolejna rzecz, która potwierdza związek między bogiem Nieba w jego strasznej roli Niszczyciela a strzyżykiem. Zwierzęciem ofiarnym Peruna i Croma Dubha był byk …

O and by the way in Japan, the wren is labelled king of the winds…

But it is possible that the hunt actually originally happened on winter solstice day but that the bird that was hunted was not wren but wran, vran meaning crow, raven.

In English tradition, „the cock robin and the jenny wren are the Queen of Heaven’s cock and hen”.

The shape-shifting Fairy Queen took the form of a wren, known as „Jenny Wren” in nursery rhymes.

W tradycji angielskiej „rudzik i strzyżyk to kogut i kura Królowej Niebios”. Zmieniająca kształt Królowa Wróżek przybrała postać strzyżyka, znanego w dziecięcych rymowankach jako „Jenny Wren”.

In my post „Babje leto – Grandmother’s summer” I talked about the transformation of the old mother goddess into Mary the mother of god, the Queen of heaven. According to the old Serbian and Celtic tradition, the year was divided into two parts: the white, light, warm part dominated by the Sky father and the black, dark, cold part dominated by the Earth Mother. These two opposites mix during the year and produce life. But in their extremes they are both destructive and bring death.

W swoim poście „Babje leto – babcine lato” mówiłem o przemianie starej bogini matki w Marię, Matkę Boga, Królową Niebios. Zgodnie ze starą serbską i celtycką tradycją rok podzielono na dwie części: białą, jasną, ciepłą, zdominowaną przez Ojca Nieba oraz czarną, ciemną, zimną, zdominowaną przez Matkę Ziemię. Te dwa przeciwieństwa mieszają się w ciągu roku i tworzą życie. Ale w swoich skrajnościach są zarówno destrukcyjne, jak i przynoszą śmierć.

The period between the Summer solstice (21st of June) and the beginning of Autumn (2nd of August), is the extreme Sky Father period. This is the period symbolized by the Eagle. The period between the Winter solstice (21st of December) and the beginning of spring (2nd of February) is the extreme Earth Mother, Baba, Cailleach period. This period is symbolized by crow and raven. In my post „Bran Vran” I talked abut the word „bran, vran, wran, fran” which is found in both Slavic and Celtic languages and which means „crow, raven” but also „black”. Crow and ravens, the ominous black birds of death are sacred birds of the mother goddess in her most extreme form as the old hag of winter.

Okres pomiędzy przesileniem letnim (21 czerwca) a początkiem jesieni (2 sierpnia) to ekstremalny okres Niebiańskiego Ojca. Jest to okres symbolizowany przez Orła. Okres pomiędzy przesileniem zimowym (21 grudnia) a początkiem wiosny (2 lutego) to okres ekstremalny dla Matki Ziemi, Baby i Cailleacha. Okres ten symbolizują wrony i kruki. W moim poście „Bran Vran” mówiłem o słowie „bran, vran, wran, fran”, które występuje zarówno w językach słowiańskich, jak i celtyckich i które oznacza „kruk, wron”, ale także „czarny”. Wrona i kruki, złowieszcze czarne ptaki śmierci, są świętymi ptakami bogini matki w jej najbardziej ekstremalnej postaci starej wiedźmy zimy.

The eagle, the big king of the summer skies and the crow, the usurper, the little king of the winter skies. Interestingly crows are the only birds which are not afraid of eagles and are known to gather in groups and attack eagles…On top of this crows and ravens are the smartest birds. So if any bird was to outsmart an eagle and use smartness against strength it would have been crow (wran) and not wren.

Orzeł, wielki król letniego nieba i wrona, uzurpator, mały król zimowego nieba. Co ciekawe, wrony to jedyne ptaki, które nie boją się orłów i są znane z gromadzenia się w grupach i atakowania orłów … Poza tym wrony i kruki to najmądrzejsze ptaki. Więc jeśli jakikolwiek ptak miałby przechytrzyć orła i użyć sprytu przeciwko sile, byłby to wrona (wran), a nie strzyżyk.

In Ireland the „wren boys” don’t actually sing „The wren, the wren, the king of all birds…”. They sing „The wran, the wran, the king of all birds…”. Is this just the mispronunciation or were the original „wren boys” actually „wran boys” who didn’t hunt wrens but „wrans”, crows and ravens?

W Irlandii „chłopcy strzyżyki” tak naprawdę nie śpiewają „Strzyżyk, strzyżyk, król wszystkich ptaków…”. Śpiewają „Wran, wran, król wszystkich ptaków…”. Czy to tylko błędne wymówienie, czy też oryginalne: „strzyżyki” faktycznie „wran chłopcy”, którzy nie polowali na strzyżyki, ale na „wranki”, wrony i kruki?

Crows and ravens can devastate the grain fields during the winter and early spring. They gather in huge flocks, land on fields and can basically poke and pull every last seed out of the ground. This is why farmers since the time immemorial considered crows their enemies and built scarecrows.

Wrony i kruki mogą spustoszyć pola zbożowe zimą i wczesną wiosną. Gromadzą się w ogromne stada, lądują na polach i mogą w zasadzie wydziobać i wyciągać z ziemi każde ziarno. Dlatego rolnicy od niepamiętnych czasów uważali wrony za swoich wrogów i budowali strachy na wróble. [CB – na wróble czy na wrony, czy tak ogólnie na ptaki, np. szpaki które wyżeraja czereśnie?]

Now here is again the picture of the „wran boys”: Macie tu teraz obrazek z wranim chłopakiem:

Don’t they look like scarecrows dressed in old mismatched colorful clothing? And look at the „straw boys”. Don’t they look like walking grain stacks?

Czy nie wyglądają jak strachy na wróble ubrani w stare, niedopasowane kolorowe ubrania? I spójrz na „słomianych chłopców”. Czy nie wyglądają jak chodzące kopki zboża?

Giant grain stacks, good harvest, is reason why crows (wrans) are killed…

Ogromne snopy zboża, dobre zbiory, to powód, dla którego zabijane są wrony …

The „wran boys” go through the fields, bang drums, blow pipes and shout. Just what you want to do if you want to scare the crows and ravens (wrans). And if you also manage to kill a crow and raven (wran) or even many crows and ravens (wrans) even better. And to prove that you have done your job of protecting the fields well, you attach the dead crows and ravens (wrans) on the holy branch and parade them through the village and you ask for money to bury them. And you kill the crows and ravens (wrans) on the day of the Winter Solstice, the day when the Sun is reborn, to help the Eagle win over crows, to help light win over darkness, to help the summer win over winter…

Chłopcy Wranowie przechodzą przez pola, walą w bębny, dmą w rury i krzyczą. Po prostu robią to, co chcesz zrobić, żeby przestraszyć wrony i kruki (wrans). A jeśli uda ci się również zabić wronę i kruka (wran) lub nawet wiele wron i kruków (wran), to jeszcze lepiej. Aby udowodnić, że dobrze wykonałeś swoją pracę, aby dobrze chronić pola, przywiązujesz martwe wrony i kruki (wranów) do świętej gałęzi i paradujesz z nimi po wiosce i prosisz o pieniądze na ich pochowanie. I zabijasz wrony i kruki (wrans) w dniu przesilenia zimowego, w dniu odrodzenia się Słońca, aby pomóc Orłu zwyciężyć wrony, pomóc światłu pokonać ciemność, pomóc latowi zwyciężyć zimę.

Remember how in Ireland wren was considered the bringer of bad news, which is the role dedicated to crows and ravens in Slavic countries where wren always brings good news? Did someone seriously misunderstand something here? I believe so. I believe that the old custom of killing crows and ravens on Winter Solstice was, when the meaning of the word „wran” was forgotten, replaced with killing of wren, which is the closest English word that sounds like „wran”…

Pamiętacie, jak w Irlandii strzyżyk był uważany za zwiastuna złych wieści, czyli grał rolę poświęconą wronom i krukom w krajach słowiańskich, gdzie strzyżyk zawsze przynosi dobre wieści? Czy ktoś tu poważnie coś źle zrozumiał? Tak mi się wydaje. Uważam, że stary zwyczaj zabijania wron i kruków podczas przesilenia zimowego, kiedy zapomniano o znaczeniu słowa „wran”, zastąpiono zabijaniem strzyżyka, które jest najbliższym angielskim słowem, które brzmi jak „wran” …

What do you think?

Co o tym myślisz?

I will leave you with this great song by Snakefinger and Residents called „Kill the great raven”. You can hear the song here.

Zostawię was z tą wspaniałą piosenką Snakefinger and Residents zatytułowaną „Kill the great Raven”. Tutaj można usłyszeć piosenkę.

Kill the Great Raven

Kill the Great Raven

His tiny eyes, they search the skies

He looks so alone, so he must die

„Oh, does he really have to die?”

„Oh yes, he really has to suffer”

Kill the Great Raven

Kill the Great Raven

And when he dies,

to his surprise

The sun will set

and he will rise

„Where will he go?”

„He’ll become the sun of course.

We must have one you know…

Kill the Great Raven

Kill the Great Raven

Zabij Wielkiego Kruka

Zabij Wielkiego Kruka

Jego maleńkie oczka, przeszukują niebo

Wygląda na tak samotnego, więc musi umrzeć

– Och, czy on naprawdę musi umrzeć?

„O tak, on naprawdę musi cierpieć”

Zabij Wielkiego Kruka

Zabij Wielkiego Kruka

A kiedy umrze,

ku jego zdziwieniu Słońce zajdzie i powstanie

„Gdzie on pójdzie?”

– Oczywiście stanie się słońcem.

Musimy mieć takiego, którego znamy …

Zabij Wielkiego Kruka

Zabij Wielkiego Kruka

źródło: http://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2016/12/wren-or-wran.html

[Sami teraz chyba widzicie jaka była droga tego podania, kto je od kogo wziął i kiedy to było – dawno, dawno temu, nie sto lat i nie 1000 ani 2000. To było około 2500-1500 lat p.n.e. CB]