Stone circles on mountain Devica

The English word karst was borrowed from German Karst in the late 19th century.[4] The German word came into use before the 19th century.[5] According to the prevalent interpretation, the term is derived from the German name for the Kras region (Italian: Carso), a limestone plateau surrounding the city of Trieste in the northern Adriatic (nowadays, located on the border between Slovenia and Italy, in the 19th century part of the Austrian Littoral).[6] Scholars however disagree on whether the German word (which shows no metathesis) was borrowed from Slovene. The Slovene common noun kras was first attested in the 18th century, and the adjective form kraški in the 16th century.[9] As a proper noun, the Slovene form Grast was first attested in 1177,[10] referring to the Karst Plateau—a region in Slovenia partially extending into Italy, where the first research on karst topography was carried out. The Slovene words arose through metathesis from the reconstructed form *korsъ,[9] borrowed from Dalmatian Romance carsus. Ultimately, the word is of Mediterranean origin, believed to derive from some Romanized Illyrian base. It has been suggested that the word may derive from the Proto-Indo-European root karra- 'rock’. The name may also be connected to the oronym Kar(u)sádios oros cited by Ptolemy, and perhaps also to Latin Carusardius.

Angielskie słowo kras zostało zapożyczone z niemieckiego „kras” pod koniec XIX wieku. [4] Niemieckie słowo zaczęło być używane przed XIX wiekiem. [5] Zgodnie z powszechnie stosowaną interpretacją termin pochodzi od niemieckiej nazwy regionu Kras (włoski: Carso), wapiennego płaskowyżu otaczającego miasto Triest na północnym Adriatyku (obecnie położone na granicy Słowenii i Włoch – jest to XIX-wieczna część wybrzeża austriackiego) [6] Uczeni nie zgadzają się jednak co do tego, czy niemieckie słowo (które nie pokazuje metatezy) zostało zapożyczone ze słoweńskiego. Słoweński rzeczownik kras został po raz pierwszy potwierdzony w XVIII wieku, a przymiotnik kraški w XVI wieku. [9] Jako właściwy rzeczownik, słoweńska forma Grast została użyta po raz pierwszy w 1177 r. [10] w odniesieniu do płaskowyżu krasowego – regionu w Słowenii częściowo rozciągającego się do Włoch, gdzie przeprowadzono pierwsze badania topografii krasowej. Słoweńskie słowa powstały w wyniku metatezy ze zrekonstruowanej formy * korsъ [9] zapożyczonej z carus z Romańskiej Dalmacji. Ostatecznie słowo to ma pochodzenie śródziemnomorskie, uważa się, że wywodzi się z jakiegoś rzymskiego, iliryjskiego rdzenia. Sugerowano, że słowo to może pochodzić od proto-indoeuropejskiego korzenia karra- „kamień/skała”. Nazwę tę można również powiązać z cytowanym przez Ptolemeusza oronym Kar (u) sádios oros, a być może także z łaciną Carusardius.

You can see that wiki says that „Ultimately, the word is of Mediterranean origin, believed to derive from some Romanized Illyrian base.” However the word has full etymology in SerboCroatian. In SerboCroatian we have following words:

Rezati, Rizati, Risati – to cut, to gouge with a toothed implement

Krš – something broken

Kršiti – to break

Kresati – to break off, to chip

Krzav – something which is jagged, toothed

Krezav – someone with missing teeth, with gaped teeth

Krist, Kras – Karst

Krist, Karst = ka + r(i)s + t(o) = like + cut, chiseled, gouged + it

Widać, że wiki mówi: „Ostatecznie słowo pochodzi z regionu śródziemnomorskiego, prawdopodobnie pochodzi z jakiegoś rzymskiego iliryjskiego rdzenia”. Jednak słowo ma pełną etymologię w języku serbsko-chorwackim. W języku serbsko-chorwackim mamy następujące słowa:

Rezati, Rizati, Risati – na cięcie, żłobienie zębatym narzędziem

Krš – coś zepsute

Kršiti – złamać

Kresati – zerwać, zetrzeć

Krzav – coś poszarpanego, zębatego

Krezav – ktoś z brakującymi zębami, z dziurawymi zębami

Krist, Kras – Kras

Krist, Karst = ka + r (i) s + t (o) = jak + ciąć, rzeźbić, wyzłobić (to)

Related to karsts are dolinas.The dolina is the most representative landform of the karst surface. The name derives from the word dolina, a Slavic term indicating any depression in the topographical surface. For nearly a century, this name acquired widespread use and a well defined meaning in the international literature; as a result it is not possible to substitute it with another term such as “vrtača” or “kraška dolina”, for example, as proposed by some authors(Gams, 1973, 1974). The use of sinkhole as a synonym for doline in the American literature has also created some ambiguity, because sinkhole is mostly applied in the sense of collapse doline or of cover doline.

Doliny są najbardziej reprezentatywnym ukształtowaniem powierzchni krasowej. Nazwa wywodzi się od słowa dolina, słowiańskiego terminu wskazującego jakiekolwiek obniżenie powierzchni topograficznej. Przez prawie sto lat nazwa ta zyskała szerokie zastosowanie i dobrze zdefiniowane znaczenie w literaturze międzynarodowej; w związku z tym nie można zastąpić jej innym terminem, na przykład „vrtača” lub „kraška dolina”, jak zaproponowali niektórzy autorzy (Gams, 1973, 1974). Użycie słowa zagłębienie/kotlina, jako synonimu doliny w literaturze amerykańskiej również wywołało niejasności, ponieważ słowo kotlina jest najczęściej stosowana w sensie zapadliska, lub doliny osłoniętej.

English Etymological dictionary says this about the English word dale:

dale (n.) – Old English dæl „dale, valley, gorge,” from Proto-Germanic *dalan „valley” (cognates: Old Saxon, Dutch, Gothic dal, Old Norse dalr, Old High German tal, German Tal „valley”), from PIE *dhel- „a hollow” (cognates: Old Church Slavonic dolu „pit,” Russian dol „valley”). Preserved by Norse influence in north of England.

dell (n.1) – Old English dell „dell, hollow, dale” (perhaps lost and then borrowed in Middle English from cognate Middle Dutch/Middle Low German delle), from Proto-Germanic *daljo (cognates: German Delle „dent, depression,” Gothic ib-dalja „slope of a mountain”); related to dale (q.v.).

Angielski Słownik etymologiczny mówi o angielskim słowie dale:

dale (n.) – staroangielskie dæl „dolina, wąwóz” z proto-germańskiego * dalan „doliny” (dotyczy: starosaskiej, holenderskiej, gotyckiej dal, staronordyckiego dal, staro-niemieckiego tal, niemieckiego tal – dolina”), od PIE * dhel-„ wydrążenie ”(oznacza: staro-cerkiewno słowiańskim dolu „dół/wądół ”,„ rosyjskie dol ”dolina”). Zachowane przez wpływy nordyckie w północnej Anglii.

dell (n.1) – staroangielski dell „dolina/kotlina, wgłębienie, dół/kotlina górska” (być może zagubiony, a następnie zapożyczony do języka średnio-angielskiego z pokrewnego średnio-holenderskiego / średnmio-dolnoniemieckiego delle), od proto-germańskiego * daljo (pokrewny: niemiecki Delle „dent , depresja”, „gockie ib-dalja” zbocze góry ”); związane z dale (q.v.).

Slavic word dole means down, depressed, hollowed out below the surface level, something below the place where we stand. Is this the root for all the above words. Proto-Germanic *dalan „valley” is identical with Slavic dolina „valley”…

The Slavic word dole comes from do + le = to + ground, horizontal, level…Le is another ancient root word. It is the root of the word level. I will talk about this word in one of my next posts.

Here is another example of a natural dolina, vrtača from central Serbia:

Słowiańskie słowo „dole” oznacza w dół, zagłębienie, wydrążenie poniżej poziomu powierzchni, coś poniżej miejsca, w którym stoimy. Czy to jest podstawa wszystkich powyższych słów? Proto-germańska * dalan „dolina” jest identyczna ze słowiańskim słowem „dolina”- w znaczeniu dolina …

Słowiańskie słowo dole pochodzi od do + le = do + ziemia/grunt, horyzont, poziom … Le to kolejne starożytne słowo rudymentarne. Jest to rdzeń/korzeń słowa poziom. Opowiem o tym słowie w jednym z moich następnych postów.

Oto kolejny przykład naturalnej doliny, vrtača (zagłębienia CB) z centralnej Serbii:

What is interesting about these landscape formations is that from their center all you can see is the edge of the hole and the sky. This makes them ideal solar observatories as I already explained in my article about rondel enclosures. There are thousands of these circular vrtača sink hole valleys strewn across Balkan peninsula.

In Slovak and Czech word vrt means to drill, a hole, a well. In SerboCroatian word „vrteti” means to spin, to turn but also to drill. This is what you do with a drill when you drill a hole, you spin it you turn it. Vrtača valleys sometimes appear suddenly and do look as if they have been drilled into the ground like this one which recently appeared in Bosnia.

Ciekawe w tych formacjach krajobrazowych jest to, że z ich centrum widać tylko krawędź dziury i niebo. To czyni je idealnymi obserwatoriami słonecznymi, jak już wyjaśniłem w moim artykule o budowlach nazywanych rondelami. Tysiące tych okrągłych dołów/ zagłębień vrtača porozrzucane są na półwyspie bałkańskim.

W słowackim i czeskim słowie vrt oznacza wiercenie, dziurę, studnię. W serbsko-chorwackim słowie „vrteti” oznacza wirowanie, obracanie, ale także wiercenie. To jest to, co robisz z wiertłem, gdy wiercisz otwór, obracasz je, obracasz. Doliny Vrtača (zagłębienia CB) czasami pojawiają się nagle i wyglądają, jakby zostały wywiercone w ziemi, jak ta, która niedawno pojawiła się w Bośni.

Eventually the edges get smoothed up and covered with vegetation. This one looks exactly like the one I used to play in when I was a kid:

Ostatecznie krawędzie zostają wygładzone i pokryte roślinnością. Ten wygląda dokładnie tak, jak kiedyś, kiedy byłem dzieckiem:

Quite often wells and lakes are found at the bottom of vrtača sink holes.

Dość często na dnie dołów vrtača znajdują się studnie i oczka wodne.

In particularly eroded karst areas vrtača sink holes accumulate the eroded soil and are the most fertile peaces of land around. This is why they are in these areas used as gardens.

W szczególnie zerodowanych obszarach krasowych vrtače owe zagłębienia CB) gromadzą glebę i są najbardziej żyznymi kawałkami ziemi w okolicy. Dlatego na tych powierzchniach zakłada się ogródki/poletka.

SerboCroatian and Slovenian word „vrt” means garden and it probably comes from the same root as vrtača.

All this makes the areas around vrtača sink holes ideal places for human habitation in karst areas where water and arable land is scarce.

There are particular types of vrtača like depressions which are mostly perfectly circular and very shallow. They look very much like a shallow pan. These vrtačas all have stone walls built at their edges and it is very difficult to determine whether they are natural vrtača sink holes cleared and walled up by people or whether they are completely artificial man made structures. Here is one from Slovenia:

Serbsko-chorwackie i słoweńskie słowo „vrt” oznacza ogród i prawdopodobnie pochodzi z tego samego źródła co vrtača.

Wszystko to sprawia, że obszary wokół zagłębień vrtača są idealnymi miejscami do zamieszkania przez ludzi na obszarach krasowych, gdzie brakuje wody i gruntów ornych.

Istnieją szczególne rodzaje vrtača, takie jak depresje, które są w większości idealnie okrągłe i bardzo płytkie. Wyglądają jak bardzo płytka patelnia. Wszystkie te vrtače mają kamienne ściany zbudowane na ich brzegach i bardzo trudno jest ustalić, czy są to naturalne otwory zagłębienia vrtača wyczyszczone i zamurowane przez ludzi, czy też są to całkowicie sztuczne konstrukcje wykonane przez człowieka. Oto jeden ze Słowenii:

Now I would like to talk about one particular Karst region of Serbia and some of its shallow pan shaped walled vrtača structures.

Devica (Virgin) is a mountain in eastern Serbia, near the town of Sokobanja. Its highest peak, Čapljinac (also called Manjin Kamen) has an elevation of 1,187 m (3,894 ft) above sea level. It belongs to the boundary of Carpatian and Balkan mountain ranges, which meet in eastern Serbia.

Teraz chciałbym porozmawiać o jednym konkretnym regionie krasowym Serbii i niektórych jego płytkich strukturach vrtača w kształcie patelni.

Devica (Dziewica) to góra we wschodniej Serbii, w pobliżu miejscowości Sokobanja. Jej szczyt, Čapljinac (zwany także Manjin Kamen), ma wysokość 1187 m npm Należy do pasm górskich Karpat i Bałkanów, które spotykają się we wschodniej Serbii.

On mountain Devica there are hundreds of vrtača sink holes and many of them belong to the above pan shaped shallow ones with stone circles built around them. These stone circles are of unknown origin and age as none of them was ever excavated or investigated by archaeologists. The stone circles were located very recently using Google maps after someone overheard a local forest warden telling his friends about strange stone formations he had seen on the mountain.

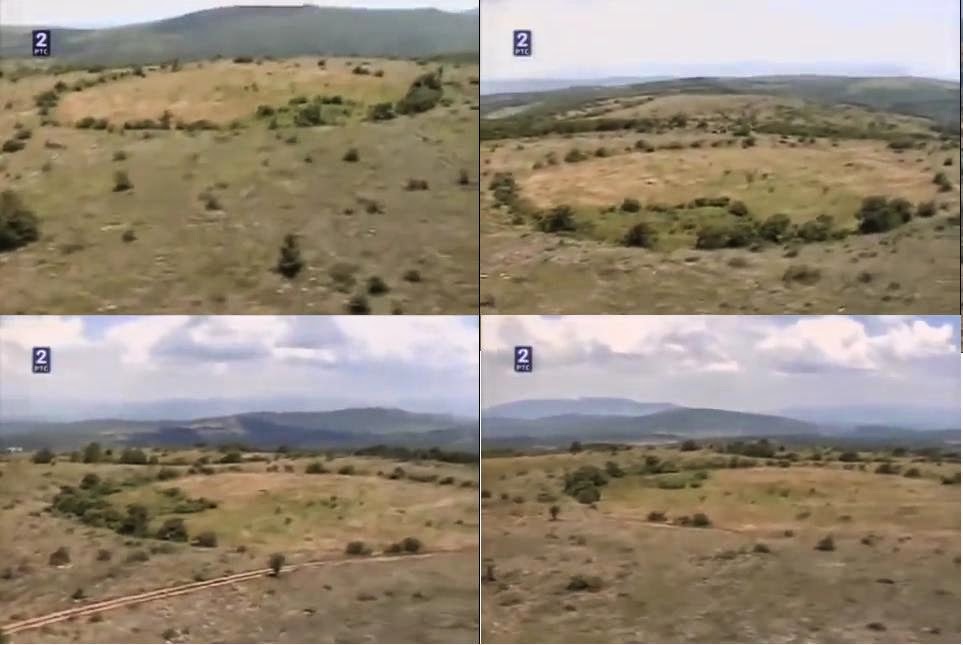

Here are the pictures of the two of these pan shaped shallow vrtača sink hole with the surrounding stone circle where you can clearly see the stone wall.

The first one is located on the hill called Gvozdinski Kamen (Iron stone).

Na górze Devica znajdują się setki zagłębień vrtača, a wiele z nich należy do wyżej położonych płytkich zagłębień z kamiennymi kręgami wokół nich. Te kamienne kręgi są nieznanego pochodzenia i wieku, ponieważ żaden z nich nie został nigdy rozkopany ani zbadany przez archeologów. Kamienne kręgi zostały niedawno zlokalizowane za pomocą Mapy Google po tym, jak ktoś usłyszał o nich od lokalnego strażnika lasu i powiedział swoim znajomym o dziwnych formacjach kamiennych, które widział na górze.

Oto zdjęcia dwóch z tych zagłębień, płytkich dołów vrtača w kształcie patelni z otaczającym je kamiennym kręgiem, gdzie wyraźnie widać kamienną ścianę.

Pierwszy znajduje się na wzgórzu o nazwie Gvozdinski Kamen (Żelazny Kamień).

The second one is located on the hill called Busarnik.

Drugi znajduje się na wzgórzu o nazwie Busarnik.

Both of these are could be natural circular depressions which people cleared of stones and then built stone walls around them or could be completely artificial. Both of them are ideal for solar observation, and could have been used for it at some stage.

But there are two more stone circles on the mountain Devica (Virgin) which are definitely completely artificial and were definitely used as solar observatories. These two stone circles are located on a plateau called „Bogovo gumno”. The circles are built as walls of what looks like a pair of of natural shallow pan shaped vrtača sink hole depressions. The bigger circle is 150 meters in diameter and the smaller one is 80 – 90 meters in diameter. The depressions are perfectly circular with perfectly flat bottom and are 50 – 60 cm lower than the surrounding therein. The stone walls which define the sides of both depressions are one meter wide and is at the moment one meter high, but originally the wall could have been much higher. This is the picture of these two stone circles from Google maps with the pointer pointing at the bigger one:

Oba są naturalnymi okrągłymi zagłębieniami, z których ludzie usuwali kamienie, a następnie budowali wokół nich kamienne ścianki, które mogą być całkowicie sztuczne. Oba są idealne do obserwacji Słońca i na pewnym etapie mogły zostać do tego wykorzystane.

Ale na górze Devica (Dziewica) są jeszcze dwa kamienne kręgi, które są zdecydowanie całkowicie sztuczne i były zdecydowanie wykorzystywane jako obserwatoria słoneczne. Te dwa kamienne kręgi znajdują się na płaskowyżu o nazwie „Bogowo Gumno”. Kręgi są zbudowane jako ściany czegoś, co wygląda jak para naturalnych płytkich wgłębień w kształcie zagłębienia vrtača. Większy okrąg ma średnicę 150 metrów, a mniejszy ma średnicę 80 – 90 metrów. Wgłębienia są idealnie okrągłe z idealnie płaskim dnem i są o 50–60 cm niższe niż otaczające je wnęki. Kamienne ściany, które wyznaczają boki obu zagłębień, mają szerokość jednego metra i obecnie mają jeden metr wysokości, ale pierwotnie ściana mogła być znacznie wyższa. Oto zdjęcie tych dwóch kamiennych kręgów z map Google ze wskaźnikiem skierowanym na większy:

What makes these two stone circles from Bogovo Gumno special, and what makes it absolutely clear that they were built and used as a solar observatory is their alignment. If you look at the alignment of the two linked stone circles on the picture below, you will see that the line connecting the centers of the two circles has azimuth 57 degrees, which means that it is aligned to the sunrise at the summer solstice. Azimuth is the angle of the sun at sunrise and sunset which may be expressed as degrees deviation from North (with East at 90 degrees). It varies by about 66 degrees over the year, from 57 degrees at the summer solstice to 122 degrees at the winter solstice. (That is, East +/- 33 degrees).

In the excellent film called „Circles on mountain Devica”, Dr Aleksandra Bajić there is a great scene (starting at 6:48) taken from a helicopter flying over the Bogovo Gumno in a circle. In these scene you can see how that particular location has completely unobstructed 360 degrees view of the sky, and is therefore ideal for solar observation. Here are some stills from the film showing the location of the Bogovo Gumno complex and the four directional view from the large circle.

You can have a look at the Bogovo Gumno circles on Google maps yourself at this coordinates here.

Możesz zobaczyć kręgi Bogowo Gumno na mapach Google na tych współrzędnych tutaj.

In my article about henges and calendars I explained how henges were used for calendar calculation. In order to determine the beginning of the year, you need to determine the day of the solstice. To do that you need a sun circle, a large circle which is permanently marked on the ground. How can you permanently mark a circle on the ground? You start by marking the centre of the circle by either a stake or a standing stone. You then draw a circle on the ground using a rope and a stick. To mark the circle edge permanently, you can build a henge if the soil is soft and easy to dig deep. But if the therein is rocky, if the soil is hard stony and unsuitable for deep digging, or if there are a lot of boulders lying around, then it is much easier to just use stones, place them along the line that defines the circle and create a permanent marking by making a circular wall.

W moim artykule na temat kręgów i kalendarzy wyjaśniłem, w jaki sposób kręgi zostały użyte do obliczenia kalendarza. Aby ustalić początek roku, musisz określić dzień przesilenia. Aby to zrobić, potrzebujesz koła słonecznego, dużego koła, które jest trwale zaznaczone na ziemi. Jak trwale oznaczyć okrąg na ziemi? Zaczynasz od zaznaczenia środka koła kołkiem lub stojącym kamieniem. Następnie narysuj okrąg na ziemi za pomocą liny i patyka. Aby trwale oznaczyć krawędź okręgu, możesz wykopać rowek, jeśli gleba jest miękka i łatwo można ją głęboko kopać. Ale jeśli jest tam skalista, jeśli gleba jest twarda, kamienista i nie nadaje się do głębokiego kopania, lub jeśli wokół leży wiele głazów, łatwiej jest po prostu użyć kamieni, umieścić je wzdłuż linii, która określa okrąg i stworzyć trwałe oznakowanie, wykonując ścianę okręgu.

Now that you have your permanently marked sun circle, you can start observing the sunrise and sunset from the center of the sun circle. What you are actually observing is the shadow made by the central stake or a standing stone. At the sunrise and sunset the shadow will be long enough to cut the circle at the oposite end. This is extremely precise way of marking the sunrise point. This stake is in Serbian known as „stožer„. This is a very interesting word which means pivot, central standing pole. The sun literally pivots around it both daily and yearly. This is a very ancient word built from stoj, staj + ga, gar, ger = standing, upright + stick, pole, stake, spear = pillar. Greeks called it „gnomon” meaning the one which knows. This was because the central stake „new” the time and date.

Teraz, gdy masz już trwale wyznaczony krąg słoneczny, możesz zacząć obserwować wschód i zachód słońca od środka koła słonecznego. To, co faktycznie obserwujesz, to cień wykonany przez kołek centralny lub stojący kamień. O wschodzie i zachodzie słońca cień będzie wystarczająco długi, aby przeciąć koło na przeciwległym końcu. Jest to niezwykle precyzyjny sposób oznaczania punktu wschodu słońca. Ten kołek centralny jest w języku serbskim znany jako „stožer”. To bardzo interesujące słowo, które oznacza czop, środkowy stojak. Słońce dosłownie obraca się wokół niego zarówno codziennie, jak i co roku. Jest to bardzo starożytne słowo zbudowane ze stoj, staj + ga, gar, ger = stać, pionowy + kij/kołek, drąg, pal, włócznia = filar. Grecy nazywali to „gnomonem”, co oznacza tego, który wie. Stało się tak, ponieważ stojak środkowy wyznacza „nowy” czas i datę.

As you observe the sunrise through the year, you will notice that during the first half of the year, the sunrise point will move further and further to the left and the point where the first shaddow cuts the circle further and further to the right. When the sunrise point stops moving to the left or when the point where the first shaddow cuts the circle stops moving to the right and starts moving back you have found the point of the summer solstice. You mark that point in some permanent way, like with a stone which is higher than the rest of the stones which form the edge of the circle.

Obserwując wschód słońca przez cały rok, zauważysz, że w pierwszej połowie roku punkt wschodu słońca będzie się przesuwał coraz bardziej w lewo, a punkt, w którym pierwszy cień przecina okrąg coraz bardziej w prawo. Kiedy punkt wschodu słońca przestaje się przesuwać w lewo lub punkt, w którym przecina się pierwszy cień, koło przestaje się przesuwać w prawo i zaczyna się cofać i tam znajduje się punkt przesilenia letniego. Zaznaczasz ten punkt w jakiś trwały sposób, na przykład kamieniem, który jest wyższy niż reszta kamieni, które tworzą krawędź koła.

Now you can easily determine the day of the summer solstice every year. It is the day when the sun, observed from the center of the sun circle, rises behind the large solstice marker stone. If you mark both summer and winter solstice turning points then the point exactly in the middle between these two points marks true east. This is the point of the spring and autumn equinox sunrise. Once you have this point and the center of the circle, you can precisely mark all four cardinal directions without use of a compass.

Teraz możesz łatwo określić dzień przesilenia letniego każdego roku. Jest to dzień, w którym słońce, obserwowane ze środka koła słonecznego, wschodzi za dużym kamieniem znacznikowym przesilenia. Jeśli zaznaczysz zarówno punkt zwrotny przesilenia letniego, jak i zimowego, to punkt dokładnie pośrodku między tymi dwoma punktami oznacza prawdziwy wschód. To jest punkt wiosennego i jesiennego wschodu równonocy. Po uzyskaniu tego punktu i środka koła możesz precyzyjnie oznaczyć wszystkie cztery główne kierunki bez użycia kompasu.

You can read in more about how the ancient sun circles were used for calendar creation in my article about rondel enclosures and my article about calendars. Once the sun circle is built and marked it can be used basically for ever. As long as the main markers are still present the observatory is functional. All we need is the two main aligned stones, the central pillar stone and the large sun stone from the edge of the circle.

Możesz przeczytać więcej o tym, jak starożytne koła słoneczne były używane do tworzenia kalendarza w moim artykule na temat obudów Rondeli i w moim artykule o kalendarzach. Po zbudowaniu i zaznaczeniu koła słonecznego można go używać zasadniczo po wsze czasy. Dopóki główne markery są nadal obecne, obserwatorium działa. Wszystko, czego potrzebujemy, to dwa główne wyrównane kamienie, kamień centralnej kolumny i duży kamień słoneczny na krawędzi koła.

In Bogovo Gumno observatory, the summer solstice turning point, was marked with a large white stone placed in the stone wall. Observer standing in the center of the large stone circle on the morning of the summer solstice would see the sun rise behind this large white sun stone. However in Bogovo Gumno the observatory builders added another stake lying outside of the sun circle in line with the center of the large sun circle and the sun stone marking the summer solstice turning point. Then the observatory builders used this second solstice turning point marker, as a central point, stožer, around which they built another smaller stone circle. The fact that we have two stone circles linked in such a way makes it impossible for them to be built around natural vrtača sink hole depressions. The chance that two perfectly circular natural vrtača sink hole depressions would naturally appear aligned in such a way is less than zero.

Several strange observation columns built form flat stones exist around the Bogovo Gumno circles looking at the main sun stone circle. This one is aligned exactly east – west. When you look through the little opening at the top of the column you look westward across Bogovo Gumno Circle.

W obserwatorium Bogovo Gumno punkt zwrotny przesilenia letniego oznaczono dużym białym kamieniem umieszczonym w kamiennej ścianie. Obserwator stojący pośrodku dużego kamiennego kręgu rano podczas przesilenia letniego zobaczyłby słońce wschodzące za tym wielkim białym kamieniem słonecznym. Jednak w Bogowie Gumno budowniczowie obserwatorium dodali kolejny kołek leżący poza kołem słonecznym w linii ze środkiem dużego koła słonecznego i kamieniem słonecznym oznaczającym punkt zwrotny przesilenia letniego. Następnie budowniczowie obserwatorium wykorzystali ten drugi znacznik punktu przesilenia, jako punkt centralny, stožer, wokół którego zbudowali kolejny mniejszy kamienny krąg. Fakt, że mamy tak połączone dwa kamienne kręgi, uniemożliwia ich budowę wokół naturalnych zagłębień w zlewach zlewni. Szansa, że dwa idealnie okrągłe naturalne wgłębienia w umywalce vrtača wydają się naturalnie wyrównane w taki sposób, jest mniejsza niż zero.

Wokół koła Bogovo Gumno istnieje kilka dziwnych kolumn obserwacyjnych zbudowanych z płaskich kamieni, z widokiem na główny kamienny krąg słońca. Ten jest ustawiony dokładnie na wschód – zachód. Kiedy patrzysz przez mały otwór na szczycie kolumny, patrzysz na zachód przez koło Bogovo Gumno.

This is another stone viewing point aligned east – west and looking at Bogovo Gumno:

To kolejny kamienny punkt widokowy ustawiony na wschód – zachód z widokiem na Bogovo Gumno:

I like these next two stone „statues” viewing points because of their weirdness. I don’t know if they are aligned and with what.

Lubię te dwa kolejne punkty widokowe z „kamiennych posągów” z powodu ich dziwności. Nie wiem czy są one wyrównane i z czym.

The astronomical complex at Bogovo Gumno is not the only man made and aligned complex of stone circles on mountain Devica.

Spójrz na te trzy wyrównane kamienne kręgi w lokacji Krst (Krzyż):

This very odd looking rock outcrop is called Oštra čuka:

To bardzo dziwnie wyglądające skalne wypiętrzenie nazywa się Oštra čuka:

In the end have a look at this stone circle with a small church built in its center:

Mountain Devica could be a huge ancient astronomical and religious center with dozens of aligned stone circles. But at the moment we just don’t know.

As I said already, none of these stone circles has ever been excavated or investigated by archaeologists.

Górska Devica może być ogromnym starożytnym centrum astronomicznym i religijnym z dziesiątkami postawionych kamiennych kręgów. Ale czy tak jest, w tej chwili po prostu nie wiemy.

Jak już powiedziałem, żaden z tych kamiennych kręgów nie został nigdy przekopany ani zbadany przez archeologów.

Also we might never be able to determine when they were built even if we do conduct archaeological investigation in the are, because they remained in use until very recently. We know that at least Bogovo Gumno complex was recognized as an astronomical observatory and was used as such by the local peasant population until the end of the 19th and the the beginning of the 20th century . This is when the last aligned stone, an anthropomorphic cross with a votive inscription was added to the Bogovo Gumno complex.

Być może nigdy nie będziemy w stanie ustalić, kiedy zostały zbudowane, nawet jeśli przeprowadzimy badania archeologiczne na ich terenie, ponieważ były one używane do niedawna. Wiemy, że przynajmniej kompleks Bogowo Gumno został uznany za obserwatorium astronomiczne i jako taki był używany przez miejscową ludność chłopską do końca XIX i na początku XX wieku. Wtedy do kompleksu Bogovo Gumno dodano ostatni ustawiony kamień, antropomorficzny krzyż z wotywnym napisem.