The third death

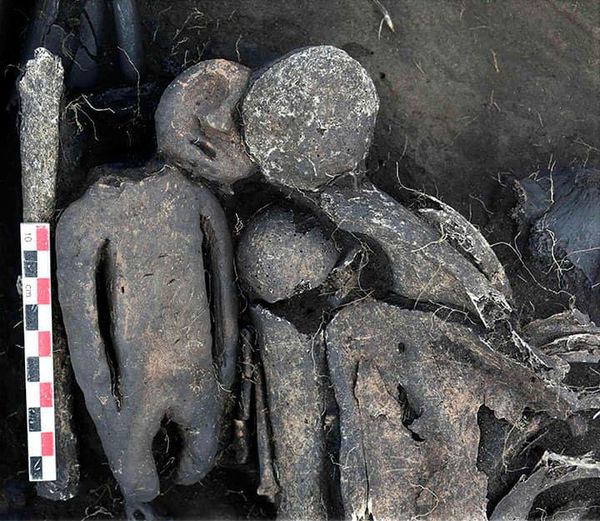

The clay figurine was perched on shoulder of a woman laid to rest about 4,000 years ago…

Gliniana figurka została zawieszona na ramieniu kobiety pochowanej około 4000 lat temu…

The woman was laid to rest on top of a man, lying on her front so that she faced him. The two of them were wrapped in a cocoon of birch bark, which was set on fire before the burial…

Kobieta została pochowana na mężczyźnie, leżąc na przodzie, twarzą do niego. Oboje byli owinięci w kokon z kory brzozowej, który przed pochówkiem podpalono…

The little statuette had a stripe going along its face, which symbolised a tattoo. It was placed on its tummy, and then its head was broken off and turned upside down so that it ‘looked up’ in a ritual yet unseen by Novosibirsk archeologists…

Mała statuetka miała pasek biegnący wzdłuż twarzy, który symbolizował tatuaż. Położono go na brzuchu, a następnie odłamano mu głowę i odwrócono go do góry nogami, tak aby „popatrzył w górę” w rytuale niewidzianym jeszcze przez nowosybirskich archeologów…

There was a deepening (slash) in the middle of the clay statuette, which had a bronze plate and also some organic substance inside it. Further chemical tests are needed to establish what exactly was placed inside that deepening.

Pośrodku glinianej statuetki znajdowało się zagłębienie (nacięcie), które zawierało brązową płytkę i wewnątrz jakąś substancję organiczną. Konieczne są dalsze badania chemiczne, aby ustalić, co dokładnie znajdowało się w tym zagłębieniu.

The bone mask made of a horse vertebrae that covered the statuette’s head depicted a bear’s muzzle, archeologists believe.

Archeolodzy uważają, że maska kostna wykonana z kręgów konia, która zakrywała głowę statuetki, przedstawiała pysk niedźwiedzia.

„…Interestingly, our anthropologists and genetics found that the Odino people were Mongoloids, yet the face of the figurine had clear Caucasian features. We don’t see the gender of the figurine, which is unusual…’ said archaeologists who discovered the figurine…

„…Co ciekawe, nasi antropolodzy i genetycy odkryli, że lud Odino był mongoloidem, a mimo to twarz figurki miała wyraźne rysy rasy kaukaskiej. Nie widzimy płci figurki, co jest niezwykłe…” – stwierdzili archeolodzy, którzy odkryłem figurkę…

Here is the best bit 🙂 „Given that the discovery is 4,000 years old, you can imagine how important it is to understand the beliefs of the ancient people populating Siberia” said the archaeologists who discovered the figurine…Well if they only asked the locals…

Oto najlepszy fragment 🙂 „Biorąc pod uwagę, że odkrycie ma 4000 lat, można sobie wyobrazić, jak ważne jest zrozumienie wierzeń starożytnych ludzi zamieszkujących Syberię” – powiedzieli archeolodzy, którzy odkryli figurkę… Cóż, gdyby tylko zapytali miejscowi…

Apparently, the Chuvash people who live in the area, bury a doll into a grave if two people from the same family suddenly die (close) together. This is done to „fool Death” so that it doesn’t take anyone else from the family, as if two die close together another one will follow

Podobno mieszkający w okolicy Czuwaski zakopują lalkę w grobie, jeśli dwie osoby z tej samej rodziny nagle umrą (blisko) razem. Ma to na celu „oszukanie Śmierci”, tak aby nie zabrała nikogo więcej z rodziny, tak jakby dwóch umarło blisko siebie, następny nastąpi

What we have hear is the same ritual performed by the people living in the same area for 4000 years…Another proof that folk traditions, beliefs and rituals could be thousands or maybe even tens of thousands of years old…And could help us understand archaeological finds…

To, co usłyszeliśmy, to ten sam rytuał odprawiany przez ludzi żyjących na tym samym obszarze od 4000 lat… Kolejny dowód na to, że tradycje ludowe, wierzenia i rytuały mogą mieć tysiące, a może nawet dziesiątki tysięcy lat… I może pomóc rozumiemy znaleziska archeologiczne…

The other day I wrote in my article „One for the road” about how Serbian folklore funerary rituals involving water, could help us understand Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age funeral practice of burying ceramic vessels with the dead…

Któregoś dnia pisałem w artykule „Jeden na drogę” o tym, jak serbskie folklorystyczne rytuały pogrzebowe z udziałem wody mogą pomóc nam zrozumieć praktyki pogrzebowe neolitu, epoki brązu i epoki żelaza polegające na zakopywaniu zmarłych naczyń ceramicznych…

In my article about „Bactrian snakes and dragons” I wrote about how Slavic folklore about snakes and dragons can help us understand the meaning of Bronze Age Bactrian seals…

W moim artykule o „wężach i smokach baktryjskich” pisałem o tym, jak słowiański folklor o wężach i smokach może pomóc nam zrozumieć znaczenie pieczęci baktryjskich z epoki brązu…

In my article „House of bones” I talked about how some Serbian beliefs and ritual related to the dead could help us solve a mystery of the missing Hittite royal bones and some weird Assyrian reliefs depicting prisoners being forced to grind the bones of their ancestors…

W moim artykule „Dom z kości” mówiłem o tym, jak niektóre serbskie wierzenia i rytuały związane ze zmarłymi mogą pomóc nam w rozwiązaniu zagadki zaginionych hetyckich kości królewskich i dziwnych asyryjskich płaskorzeźb przedstawiających więźniów zmuszanych do mielenia kości swoich przodków. ..

The other day, in my article about „Cock bashing” end of harvest ritual in Sorbia, I wrote about how cockerel sacrifice was among Serbs used as a replacement for human sacrifice performed at the end of the harvest…

Któregoś dnia w moim artykule na temat rytuału zakończenia żniw w Serbii „uderzenia kogutów” pisałem o tym, jak wśród Serbów składano ofiary z kogutów jako zamiennik ofiar z ludzi składanych pod koniec żniw…

Also in my post about „New house” I talked about obvious replacement of the human sacrifice with a sacrifice of a cock…

Również w moim poście o „Nowym domu” mówiłem o oczywistym zastąpieniu ofiary ludzkiej ofiarą z koguta…

„It was believed that someone from the family will soon die after they move into the new house, because every house wants to have its protective spirit, which is the spirit of the first person to die in the house. To prevent this from happening, the man of the new house would kill a cockerel on the house doorstep (the seat of the dead) and would sprinkle all four corners of the house with its blood…”

„Uważano, że ktoś z rodziny wkrótce po przeprowadzce do nowego domu umrze, bo każdy dom chce mieć swojego ducha opiekuńczego, czyli ducha pierwszej osoby, która w domu umiera. Aby temu zapobiec, człowiek nowego domu zabije koguta na progu domu (siedzibie umarłych) i pokropi jego krwią wszystkie cztery narożniki domu…”

Interestingly, Serbs have identical ritual to the one performed by the Siberian Chuvash people when two members of the family die close together. Except that Serbs then bury „a live cockerel” with the dead „to fool Death” or more precisely „as a replacement for the third death”…

Co ciekawe, Serbowie mają identyczny rytuał jak ten, który wykonują syberyjscy Czuwasze, kiedy dwóch członków rodziny umiera blisko siebie. Tyle że Serbowie grzebią wówczas „żywego koguta” razem ze zmarłymi „w celu oszukania Śmierci”, a dokładniej „w zastępstwie trzeciej śmierci”…

So another proof that cockerel was seen by Serbs as a replacement for people, and another proof that these beliefs and rituals were once (Bronze Age, Neolithic, Even Earlier???) possibly common across Eurasia…

Zatem kolejny dowód na to, że Kogucik był postrzegany przez Serbów jako zamiennik człowieka i kolejny dowód na to, że te wierzenia i rytuały były kiedyś (epoka brązu, neolit, nawet wcześniej???) prawdopodobnie powszechne w całej Eurazji…

Or maybe we should just dismiss all this as just a coincidence. And we should continue to ignore our folklore and continue to „wonder what could possibly be the belief system of our Bronze Age ancestors”…

A może powinniśmy po prostu odrzucić to wszystko i uznać to za zbieg okoliczności. Powinniśmy w dalszym ciągu ignorować nasz folklor i nadal „zastanawiać się, jaki mógłby być system wierzeń naszych przodków z epoki brązu”…

źródło: https://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2021/02/the-third-death.html