Babji mlin – Grandmother’s mill (Babi młyn)

Panjska končnica is the name used for the painted front panel of „kranji” beehives (Carniolan beehives).

Panjska končnica to nazwa używana na malowany przedni panel uli „kranji” (ule kraińskie).

This type of folk art, characteristic of Slovenia originally appeared in the Gorenjska and Slovenian Carinthia, and from there it spread to the entire territory of Slovenia. The oldest painted beehive panels date back to the middle of the 18th century and the last ones were painted just before the First World War. During this period, approximately 150 years, more than 50,000 of these painted beehive panels were made. The painting was usually done by self-taught naive painters who used mostly natural pigments and linseed oil, which made the colours more durable. There are more than 600 different known motifs which were painted on the beehive panels of which about half are religious.

Ten typ sztuki ludowej, charakterystyczny dla Słowenii, pierwotnie pojawił się w Gorenjskiej i słoweńskiej Karyntii, a stamtąd rozprzestrzenił się na całe terytorium Słowenii. Najstarsze malowane panele ula pochodzą z połowy XVIII wieku, a ostatnie powstały tuż przed I wojną światową. W tym okresie, około 150 lat, wykonano ponad 50 000 takich malowanych paneli ulowych. Malarstwo było zwykle wykonywane przez naiwnych malarzy-samouków, którzy używali głównie naturalnych pigmentów i oleju lnianego, dzięki czemu kolory były trwalsze. Istnieje ponad 600 różnych znanych motywów, które zostały namalowane na panelach ula, z których około połowa ma charakter religijny.

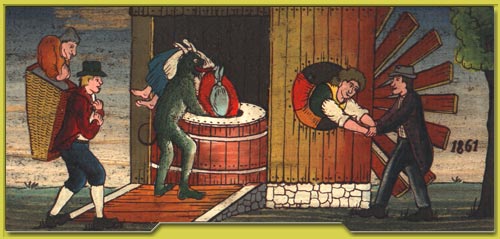

One of the most interesting motifs found on the beehive panels is called „Babji mlin” meaning „Grandmother’s mill”. It depicts an old, ugly woman, being thrown into a grain mill by either a man or a devil. She comes out of the mill transformed into a beautiful young woman.

Jeden z najciekawszych motywów znalezionych na panelach ula to „Babji mlin”, czyli „młyn Babci”. Przedstawia starą, brzydką kobietę, wrzucaną do młyna przez mężczyznę lub diabła. Wychodzi z młyna przemieniona w piękną młodą kobietę.

The history of this motif was explored by Niko Kuret in his work „Babji mlin, Prispevek k motiviki Slovenskih panjskih končnic„. In it we can read that the earlier depiction of the „Babji mill” scene is the 1600 Dutch woodcut, depicting the scene taking place in a windmill. The copper engraving from Augsburg which dates to around 1630 and also depicts the scene in a windmill. In 1672 we have the first depiction of the „Babji mlin” in England in the book entitled „The merry Dutch miller and new invented windmill”. The Munich museum has an engraving from 1800 depicting the „Babji mlin” scene entitled „The art of turning an old woman into a young one in a mill”. There is also an engraving from Nürnberg dated to 1810 depicting the same scene and another engraving from 1810 from Berlin, which is the first known depiction of this scene taking place in the water mill. The color lithographs by Gustav Kühn from Neuruppin made around 1820-1830, in addition to rejuvenation of women also show the rejuvenation of men in a mill. This is also the period to which the oldest depictions of the „Babji mlin” from Slovenija were dated, the oldest being the one on a beehive panel currently kept in an ethnographic museum in Ljubljana, dated to 1861.

Historię tego motywu zgłębił Niko Kuret w swojej pracy „Babji mlin, Prispevek k motiviki Slovenskih panjskih končnic”. Czytamy w nim, że wcześniejszym przedstawieniem sceny „młyn Babji” jest drzeworyt holenderski z 1600 roku, przedstawiający scenę rozgrywającą się w wiatraku. Miedzioryt z Augsburga, datowany na około 1630 r., przedstawia również scenę w wiatraku. W 1672 roku mamy pierwsze przedstawienie „Babji mlin” w Anglii w książce zatytułowanej „Wesoły holenderski młynarz i nowo wynaleziony wiatrak”. W monachijskim muzeum znajduje się rycina z 1800 roku przedstawiająca scenę „Babji mlin” zatytułowana „Sztuka przemieniania starej kobiety w młodą w młynie”. Jest też rycina z Norymbergi z 1810 roku przedstawiająca tę samą scenę oraz inna rycina z 1810 roku z Berlina, która jest pierwszym znanym przedstawieniem tej sceny rozgrywającej się w młynie wodnym. Kolorowe litografie Gustava Kühna z Neuruppin wykonane około 1820-1830 oprócz odmładzania kobiet pokazują również odmładzanie mężczyzn w młynie. Na ten okres datowane są również najstarsze przedstawienia „Babji mlin” ze Słowenii, z których najstarszym jest ten na panelu ula znajdujący się obecnie w muzeum etnograficznym w Lublanie, datowany na 1861 rok.

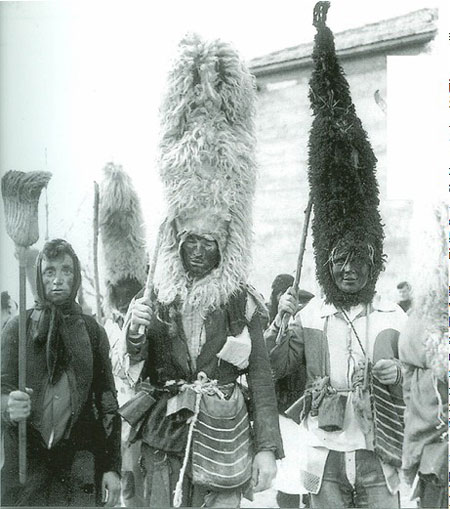

The „Babji mlin” motif is not only found depicted as a painting. It is also found in the form of dramatic performances, games, as part of carnival customs. The earliest surviving description of the „Babji mlin” dramatic performance is from the Cologne carnival from from 1850. The same scene was part of carnival procession in Swizerland until 1900, and in Brixlegg in Tirol the „Babji mill” was part of the carnival procession until 1862. The same tradition was recorded in Wipptal, Glurns, Innsbruck and many other parts of Switzerland. In the mid 19th century, „Babji mlin” was also described as being part of the carnival processions in many parts of lower Austria: Salzburg, Leibniz, Štajerska, Gradišće and Frohnleiten, a town in the district of Graz. In Slovenija „Babji mlin” was part of the carnival processions in many areas. Here is a depiction of the „Babji mlin” from Dobropolje, drawn based on the description of an eyewitness from the beginning of the 20th century.

What is interesting is that there is actually a folk story about the magic mill which would „turn old women into young and grind (destroy) the evil ones”. The same type of story was recorded in Slovenija, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Czech republic.

Co ciekawe, faktycznie istnieje ludowa opowieść o magicznym młynie, który „zamieniałby stare kobiety w młode i miażdżył (niszczył) złe”. Ten sam rodzaj historii odnotowano w Słowenii, Niemczech, Austrii, Szwajcarii i Czechach.

I believe that the story depicting the „Babji mlin” scene existed first. The story was then enacted as part of the carnival and it was then depicted as a „curio” on engravings and paintings. But what does this strange scene represent?

As I said already in my posts „Baba – earthen bread oven„, in Serbian and other Slavic languages, the word „baba” means baby, mother, grandmother, midwife, birth demon and eventually great goddess, Mother earth the mother of all of us.

Jak już wspomniałem w moich postach „Baba – gliniany piec chlebowy”, w języku serbskim i innych słowiańskich słowo „baba” oznacza dziecko, matkę, babcię, położną, demona narodzin i ostatecznie wielką boginię, Matkę Ziemię, matkę wszystkich nas.

I believe that the „Babji mlin” is a depiction of a transformation of the ugly, barren, cold, old hag (winter earth) into a beautiful, fertile, hot, young woman (summer earth). This transformation, the end of winter and beginning of summer according to the old Celtic and Serbian calendar, happens on the St George’s day, the day of Jarilo, Beltane, which falls on the 6th of May. I wrote about the significance of this date in my post about the Beltany stone circle. The celebration of the first day of summer was in Christianity replaced with Easter which falls right after the carnival during which the old woman is transformed into a young one in „Babji mlin”. The carnival falls into the period just before the first crops are about to arrive. This is the time when the last winter reserves are being eaten and it is an imperative that the earth is rejuvenated, married, impregnated and that she starts giving birth to crops. So when the mother Earth is transformed into a fertile young earth in the the Babji mlin, it is married to a young sun, Jarilo. This is the sacred marriage between the sun and earth which produces all life and is enacted during carnivals in Serbia and Croatia as the scene knows as „Baba i Djedi” (Grandmother and Grandfathers).

Wierzę, że „Babji mlin” przedstawia przemianę brzydkiej, jałowej, zimnej, starej wiedźmy (zimowej ziemi) w piękną, płodną, gorącą, młodą kobietę (zimowa ziemia). Ta przemiana, koniec zimy i początek lata według starego kalendarza celtyckiego i serbskiego, ma miejsce w dzień św. Jerzego, dzień Jarilo, Beltane, który przypada 6 maja. O znaczeniu tej daty pisałem w swoim poście o kamiennym kręgu w Bełtanach. Świętowanie pierwszego dnia lata zostało w chrześcijaństwie zastąpione Wielkanocą, która wypada zaraz po karnawale, podczas którego stara kobieta zmienia się w młodą w „Babji mlin”. Karnawał przypada na okres tuż przed zbliżającymi się pierwszymi plonami. To czas, kiedy zjadane są ostatnie zapasy na zimę, a ziemia jest w końcu odmłodzona, zamężna, zapłodniona i też zaczyna rodzić plony. Kiedy więc matka Ziemia zostaje przekształcona w żyzną młodą ziemię w Babji mlin, zostaje poślubiona młodemu słońcu, Jarilo. Jest to święte małżeństwo między słońcem a ziemią, które daje życie i jest odgrywane podczas karnawału w Serbii i Chorwacji, jako scena znana jako „Baba i Djedi” (Babcia i Dziadkowie).

Baba (Grandmother) and Djedovi (Grandfathers) Dalmatinska zagora mid 20th Century

Baba (babcia) i Djedovi (dziadkowie) Dalmatinska zagora połowa XX wieku

Baba (Grandmother) and Djedovi (Grandfathers) Serbia mid 20th Century

Baba (babcia) i Djedovi (dziadkowie) Serbia, połowa XX wieku

But why is the regeneration of Baba, Mother Goddess, Mother Earth taking place in the mill?

Ale dlaczego regeneracja Baby, Bogini Matki, Matki Ziemi odbywa się w młynie?

In Serbia a mill is considered to be a magic place. Mill is said to have been invented by the devil himself. The devil is also believed to be permanently present in mills and that he sometimes takes shape of a miller. During famines and hungry days, like carnival, it is believed that the devils and vampires and ghosts (spirits of ancestors) congregate around mills and granaries. So as a seat of the devil (old god Dabog, the giving god, The Sky Father), a mill is an ideal place to rejuvenate Mother Earth and make her young and beautiful again. In Serbia there is a belief that rainbow draws its water and its beauty from the pool beneath the water mill wheel. The water which drips from the water mill wheel and the water from the pool below the water mill wheel is believed to have special properties. Girls wash themselves in this water which is called „omaja, omaha” because it is believed that it will make them beautiful and irresistible to men. Young people bath in the pool next to the water mill wheel on St George’s day, Jarilo’s day, the first day of Summer, the day when winter turns into summer, to gain health, fertility and beauty. If a woman can’t have children, she goes to the water mill with her husband, he grabs some water from the pool below water mill wheel with rakes, and gives it to her to drink it. It is believed that this will make woman fertile.

W Serbii młyn uważany jest za magiczne miejsce. Mówi się, że młyn został wynaleziony przez samego diabła. Uważa się również, że diabeł jest stale obecny w młynach i że czasami przybiera postać młynarza. Uważa się, że podczas głodu i dni gołoty, takich jak karnawał, diabły, wampiry i duchy (duchy przodków) gromadzą się wokół młynów i spichlerzy. Tak więc, jako siedziba diabła (stary bóg Dabog, bóg obdarowywania, Ojciec Nieba), młyn jest idealnym miejscem do odmłodzenia Matki Ziemi i uczynienia jej znowu młodą i piękną. W Serbii panuje przekonanie, że tęcza czerpie wodę i swoje piękno z sadzawki pod kołem młyńskim. Uważa się, że woda, która kapie z koła młyńskiego i woda z basenu pod kołem młyńskim ma szczególne właściwości. Dziewczęta myją się w tej wodzie, która nazywa się „omaja, omaha”, ponieważ uważa się, że dzięki niej staną się piękne i nieodparte dla mężczyzn. Młodzi ludzie kąpią się w basenie obok młyna wodnego w dzień św. Jerzego, w dzień Jaryły, w pierwszy dzień lata, w dzień, w którym zima przechodzi w lato, aby zyskać zdrowie, płodność i urodę. Jeśli kobieta nie może mieć dzieci, idzie z mężem do młyna, on łapie grabkami wodę z basenu pod kołem młyńskim i daje jej do picia. Uważa się, że dzięki temu kobieta będzie płodna.

So mill is in South Slavic folklore considered to be the place which contains special powers particularly when it comes to rejuvenating and ensuring fertility. So there is no wander that the mill was chosen as the place where the scene of the the rejuvenation of the Mother Earth takes place. But there is another reason why the rejuvenation scene takes place in a mill. Mill is the place where grain is turned into flour. It is therefore directly linked with the grain fertility magic, and the Mother Earth is in agricultural societies directly linked to grain and bread. She is the Mother of Grain, the Spirit of Grain and the grain and ultimately bread itself.

Młyn więc w folklorze południowosłowiańskim uważany jest za miejsce, które ma w sobie szczególne moce, zwłaszcza jeśli chodzi o odmładzanie i zapewnianie płodności. Nie ma więc co się dziwić, że młyn został wybrany jako miejsce, w którym rozgrywa się scena odmłodzenia Matki Ziemi. Ale jest jeszcze jeden powód, dla którego scena odmłodzenia rozgrywa się w młynie. Młyn to miejsce, w którym ziarno zamienia się w mąkę. Jest zatem bezpośrednio powiązany z magią płodności zboża, a Matka Ziemia jest w społeczeństwach rolniczych bezpośrednio związana ze zbożem i chlebem. Ona jest Matką Zboża, Duchem Zboża i ziarna, a ostatecznie samym chlebem.

This link is preserved in Slavic traditions and languages.

bа̏bičiti – to make, to tie grain sheaves

baba – sheaf of grain, wheat

Ten związek jest zachowany w słowiańskich tradycjach i językach.

bа̏bičiti – robić, wiązać snopki zboża

baba – snop zboża, pszenica

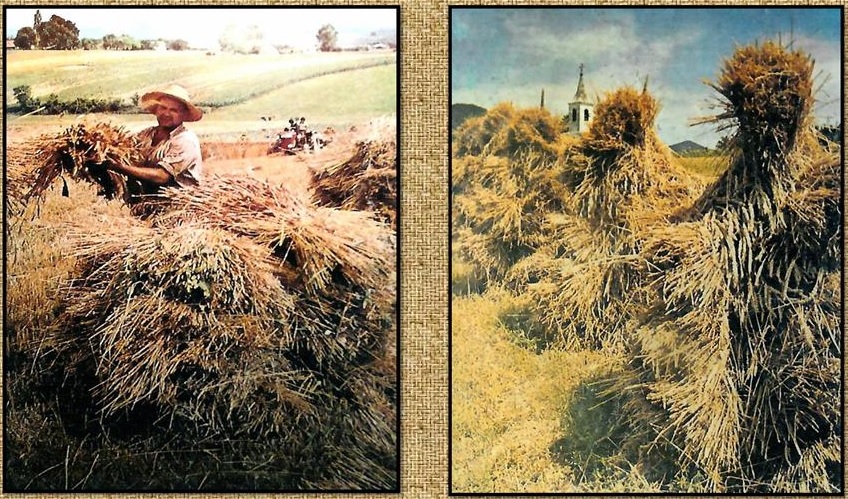

To me a sheaf of wheat even looks like a woman. And if we know that in South Slavic languages baba is a fertile woman, a woman who had children, a mother then there is no wonder why a sheaf full of grain is called baba.

Dla mnie snopek pszenicy wygląda nawet jak kobieta. A jeśli wiemy, że w językach południowosłowiańskich baba to kobieta płodna, kobieta, która miała dzieci, matka, to nie ma się co dziwić, że snop pełen zboża nazywany jest babą.

Czech: baba – last sheaf brought from the field

Lower Lusatian: baba – sheafs of linnen

Slovenian: babica – stack of sheafs left on the field

Russian: babka – stack of sheafs, sheaf

Bulgarian: babka – stack of 5,10,15 sheafs

Croatian: baba – top most sheaf on the sheaf stack

Czeski: baba – ostatni snop przyniesiony z pola

Dolnołużyckie: baba – snopki lniane

Słoweński: babica – stos snopów pozostawionych na polu

Rosyjski: babka – stos snopów, snop

Bułgarski: babka – stos 5,10,15 snopów

Chorwacki: baba – najwyższy snop na stosie snopów

In Slovenija in the old times, during the harvest all the neighbors helped each other. First the reapers would come to the field and would begin to reap. The first sheaf of wheat was always raised to the sky, which is a remnant of the old sacrificial ritual of thanksgiving. The last sheaf, called baba, was believed to be the residence of the grain spirit. After the harvest this grain spirit had to be killed. The grain spirit was killed by hitting the baba sheaf with a hand. Men would then load the sheaves on to the cart. The ears of grain left on the field were considered to be sacrificial offerings to the grain spirit.

W Słowenii w dawnych czasach podczas żniw wszyscy sąsiedzi pomagali sobie nawzajem. Najpierw na pole przychodzili żniwiarze i zaczynali żąć. Pierwszy snop pszenicy był zawsze podnoszony do nieba, co jest pozostałością po dawnym ofiarnym rytuale dziękczynienia. Wierzono, że ostatni snop, zwany babą, był siedzibą ducha zbożowego. Po żniwach duch zbożowy musiał zostać zabity. Ducha zboża zabijano, uderzając ręką w snopek baby. Następnie mężczyźni ładowali snopy na wóz. Kłosy pozostawione na polu uważano za ofiary składane duchowi zbożowemu.

Harvested grain was then dried on hay-racks called kozolec meaning goat. Sometimes a carved image of a goat made of wood, called God’s goat, was affixed on the front of the hay-rack. Bundles of wheat were hanged on its horns, and were left there until the new harvest. It was believed that such decorated hay-rack would not be struck by lightning. A goat was in fact an animal dedicated to Perun, Slavic god of thunder and lightning.

Zebrane zboże suszono następnie na stogach zwanych kozolecami, czyli kozimi. Czasami na przodzie stogu umieszczano wyrzeźbiony w drewnie wizerunek kozła, zwanego kozłem Bożym. Wiązki pszenicy zawieszono na jego rogach i pozostawiono tam aż do nowych żniw. Wierzono, że tak udekorowany stóg zboża / slomy nie uderzy piorun. Koza była w rzeczywistości zwierzęciem poświęconym Perunowi, słowiańskiemu bogu piorunów i błyskawic.

The last cart was usually loaded higher at the back and lower in front. A tall straw doll called Baba was placed with rakes at the rear of the cart. The cart driver would cup with a whip and cry out: „We brought the baba, give us drink for her.”

Ostatni wózek był zwykle ładowany wyżej z tyłu i niżej z przodu. Z tyłu wozu umieszczono wysoką słomianą lalkę o imieniu Baba wraz z grabiami. Woźnica bił batem i wołał: „Przynieśliśmy babę, daj nam za nią pić”.

I will talk more about the significance of the last sheaf in European tradition in one of my next posts. But it is important to note that in South Slavic languages the sheaf, the top sheaf, the last sheaf and the effigy, doll, made from the last harvested grain are all called baba.

O znaczeniu ostatniego snopka w tradycji europejskiej opowiem szerzej w jednym z kolejnych wpisów. Ale ważne jest, aby pamiętać, że w językach południowosłowiańskich snopek, górny snop, ostatni snop i kukły, lalki, wykonane z ostatniego zebranego zboża, nazywane są baba.

Pisałam już, że baba to także nazwa tradycyjnego glinianego pieca chlebowego. To baba (mężatka, matka) nosi dziecko w brzuchu (piec chlebowy). Dziecko (chleb) musi spędzić odpowiednią ilość czasu w brzuchu (piekarniku) baby (matki, piekarnika), aby prawidłowo rosnąć i rozwijać się. To baba (teściowa lub inna starsza kobieta, która ma doświadczenie przy porodzie, później zawodowa położna (wypiek chleba) rodzi dziecko (chleb).

In Slavic countries baba is also name used for various ritual breads linked to ancestor worship.

So far we have seen that in Slavic countries baba is the name used for sheaf of wheat, for bread oven and for ritual breads. Baba is also the name used for great goddess, Great Mother, Mother Eearth. Mother Earth who gives birth to wheat, year after year after year. But even Mother earth can get barren and infertile after years of giving birth to harvest after harvest after harvest. Just like an old woman who has given birth to many children eventually becomes exhausted, infertile and barren.

Jak dotąd widzieliśmy, że w krajach słowiańskich baba to nazwa używana dla snopka pszenicy, dla pieca chlebowego i dla rytualnych chlebów. Baba jest także imieniem wielkiej bogini, Wielkiej Matki, Matki Ziemi. Matka Ziemia, która rodzi pszenicę, rok po roku, rok po roku. Ale nawet Matka Ziemia może stać się jałowa i bezpłodna po latach rodzenia, żniwach za żniwami. Tak jak stara kobieta, która urodziła wiele dzieci, w końcu staje się wyczerpana, płonna i bezpłodna.

But there are two ways in which an old exhausted barren land can be rejuvenated, made young and fertile again: by water and fire.

Istnieją jednak dwa sposoby, dzięki którym stara, wyczerpana, jałowa ziemia może zostać odmłodzona, odmłodzona i ponownie urodzajna: za pomocą wody i ognia.

Floods bring and deposit nutrients which have been depleted by crops. Regular yearly floods ensure that the Mother Earth is rejuvenated every year and is fertile and fruitful as if she was a virgin land. It is no wonder then that it was in the alluvial and flood plains that grain agriculture developed and flourished in the early Neolithic times. The soil is sandy and therefore easy to work, it is rich and gives high yields, and it is regularly enriched with new flood deposits preventing soil depletion, which was the main problem for early farmers. I wrote about this in my post about Blagotin archaeological site.

Powodzie przynoszą i osadzają składniki odżywcze, które zostały wyczerpane przez uprawy. Regularne coroczne powodzie zapewniają, że Matka Ziemia co roku odmładza się i jest żyzna i płodna, jak gdyby była dziewiczą krainą. Nic więc dziwnego, że to właśnie na terenach aluwialnych i zalewowych rozwijało się i kwitło rolnictwo zbożowe we wczesnym neolicie. Gleby są piaszczyste, a więc łatwe w uprawie, bogate i dają wysokie plony, regularnie wzbogacane o nowe osady powodziowe, zapobiegające wyczerpywaniu gleby, co było głównym problemem wczesnych rolników. Pisałem o tym w poście o stanowisku archeologicznym Blagotin.

The vegetation burning is the other way to return the nutrients drawn out by the plants into the soil. By regularly burning of the plants in the autumn returns the nutrients back into the soil and makes it rich again.

Spalanie roślinności to inny sposób na powrót składników odżywczych wyciągniętych przez rośliny do gleby. Regularne wypalanie roślin jesienią przywraca składniki odżywcze do gleby i ponownie ją wzbogaca.

What is interesting is that the „Babji mlin”, the scene in which an old woman is thrown into a mill only to emerge as a young woman on the other side, is not the only depiction of the rejuvenation scene. There are, according to Niko Kuret, two more depictions of the rejuvenation scene. In the first an old woman walks into a well only to emerge as a young girl on the other side. Is this a depiction of the floods rejuvenating Mother Earth? In the second, an old woman walks into a forge or an oven only to walk out as a young girl. Is this a depiction of the fire rejuvenating Mother Earth?

Co ciekawe, „Babji mlin”, scena, w której stara kobieta zostaje wrzucona do młyna, by po drugiej stronie wyłonić się jako młoda kobieta, nie jest jedynym przedstawieniem sceny odmłodzenia. Według Niko Kureta istnieją jeszcze dwa przedstawienia sceny odmłodzenia. W pierwszym stara kobieta wchodzi do studni, by po drugiej stronie wynurzyć się jako młoda dziewczyna. Czy to przedstawienie powodzi odmładzających Matkę Ziemię? W drugim stara kobieta wchodzi do kuźni lub pieca, by wyjść jako młoda dziewczyna. Czy to jest przedstawienie ognia odmładzającego Matkę Ziemię?

So I believe that here we have discovered something very interesting. I believe that the the scene called „Babji mlin” is a remnant of the ancient fertility ritual related to the annual rejuvenation of the Mother Earth, Great Goddess. Every 4th of February, at the beginning of spring, she is transformed from the old, ugly, cold, barren winter Earth into the young, beautiful, hot, fertile Spring Earth. This transformation happens under the influence of her husband, Father Sky, Great God to whom she is then married on the 6th of May, at the beginning of summer.

Uważam więc, że tutaj odkryliśmy coś bardzo interesującego. Wierzę, że scena zwana „Babji mlin” jest pozostałością starożytnego rytuału płodności związanego z corocznym odmładzaniem Matki Ziemi, Wielkiej Bogini. Każdego 4 lutego, na początku wiosny, zmienia się ze starej, brzydkiej, zimnej, jałowej zimowej Ziemi w młodą, piękną, gorącą, urodzajną Ziemię Wiosny. Ta przemiana zachodzi pod wpływem jej męża, Ojca Nieba, Wielkiego Boga, z którym zostaje poślubiona 6 maja, na początku lata.

Co myślisz?

What do you think?