The Origin of Anglo – Saxon race

Przedstawiam to obszerne tłumaczenie żeby pokazać dobitnie jak zakłamana jest allochtoniczna propagandowa, germańska Teoria o Wielkiej Pustce Osadniczej w Europie Nadłabsko-Odrzańsko-Wiślańsko-Bałtyckiej w Epoce Późno-rzymskiej od 1 wieku pne do V wieku ne. W książce znajduje się też szereg ciekawych dowodów antropologicznych o rasie Słowian w powiązaniu z danymi z kronik rzymskich – a więc dowodów na istnienie potężnej i zorganizowanej Słowiańszczyzny Starożytnej w Epoce Starożytności, czyli czasach rozkwitu i upadku cywilizacji Grecji, Persji, Egiptu i Rzymu.

I recommend the book as a must read for anyone who wants to understand the Iron Age and early medieval Baltic and its relationship with British Isles and Ireland. It opened my eyes and showed me the link between the Iron Age invasions and Viking invasions of British Isles. It also shows the extent of intermixing between the Germanic and Slavic people of the South Baltic area.

Origin of the Anglo Saxon raceTHE SAXONS AND THEIR TRIBES

Polecam tę książkę jako obowiązkową lekturę każdemu, kto chce zrozumieć epokę żelaza i wczesnośredniowieczny o0bszar Bałtyku oraz jego związek z Wyspami Brytyjskimi i Irlandią. Otworzyło mi to oczy i pokazało mi związek między najazdami epoki żelaza a najazdami Wikingów na Wyspy Brytyjskie. Pokazuje również stopień wymieszania się ludów germańskich i słowiańskich z obszaru południowego Bałtyku.

Ω

Pochodzenie rasy anglosaskiej SASI I ICH PLEMIENIA – Thomas William Shore

Od tak dawna przywykliśmy nazywać niektórych angielskich osadników Sasami, że z pewnym zdziwieniem dowiadujemy się żadni z nich nie nazywali się sami tym mianem. Jeśli chodzi o Anglię, pod taką nazwą byli powszechnie określani przez Brytyjczyków, a sami ci ludzie powszechnie zaczęłi używać owej nazwy dopiero kilka wieków później. Narody i plemiona, jak również jednostki, są zawsze znane albo z imion rodzimych, albo z imion, które nadają im inni ludzie. W konsekwencji mogą mieć więcej niż jedno miano. Nazwa Saxon, chociaż nie jest używana przez plemiona, które najechały Anglię w piątym i szóstym wieku jako ich własne określenie, jest starsza niż ta inwazja.

Przed końcem panowania rzymskiego w Wielkiej Brytanii używano go do oznaczania części wybrzeża angielskiego od Wash do Solent i wybrzeża kontynentalnego północno-wschodniej Francji i Belgii, które były znane jako Wybrzeże Saskie. Nazwa ta najwyraźniej wzięła się od pochodzenia piratów, których nazywano Sasami. Z drugiej strony istnieją dowody prowadzące do wniosku, że na tych wybrzeżach istniały wczesne osady ludzi zwanych Sasami. Oba te poglądy mogą być słuszne, ponieważ piraci Sasi, podobnie jak mieszkańcy północy w późniejszych wiekach, mogli najpierw splądrować wybrzeża, a następnie osiedlić się wzdłuż nich. W każdym razie do opieki nad tymi brzegami wyznaczono rzymskiego urzędnika lub admirała, znanego jako Comes litoris Saxonici [1], namiestnik wybrzeża saskiego. Po odejściu legionów rzymskich częściowo zornanizowani Brytyjczycy w naturalny sposób nadali najeźdźcom z Niemiec nazwę Saxon, gdyż ta nazwa pochodziła do nich z okresu rzymskiego, bo po czasach Konstantyna Wielkiego wszyscy mieszkańcy wybrzeży Germanii, którzy praktykowali piractwo, byli objęci nazwą Sasi (Saxoni).[2] To ciekawa okoliczność, że części Anglii, w których Saksończycy nazywają miejscowości, takie jak Sexebi i Sextone, które przetrwały w czasie badania Domesday, nie znajdują się w tych hrabstwach, które należały do któregokolwiek z saksońskich królestw Anglii. Rozważając problem nazwa Sasów pojawia się przed nami w szerszym znaczeniu niż plemię, jako oznaczająca plemiona działające razem, praktycznie konfederacja. W tym sensie była używana przez wczesnych pisarzy brytyjskich, Anglów Jutów i ludzi z innych plemion. Wszyscy pozostali byli dla nich Sasami, a osadnicy we wszystkich częściach Anglii byli znani jako Sasi, podobnie jak mieszkańcy Sussex, Essex i Wessex. W tym szerszym sensie Bede używał nazwy Saxonia, gdyż chociaż był Anglikiem, określał się jako sprawujący urząd w Saksonii. Osadnicy w Hampshire, którzy po pewnym czasie byli znani wspólnie z mieszkańcami sąsiednich hrabstw jako West Saxons, nie nazywali siebie Sasami, lecz Gewissas, a najbardziej prawdopodobnym znaczeniem tej nazwy są konfederaci, czyli ci, którzy działają razem w jakiejś trwałej więzi zjednoczenia. [3] Ich późniejsza nazwa Sasów Zachodnich była najwyraźniej geograficzna. Nazwę Saksonowie bez wątpienia uznano za wygodną dla opisania ludu plemiennego, który migrował do Anglii z północnych wybrzeży Germanii, rozciągających się od ujścia Renu do Wisły , ale między sobą Sasi byli z pewnością znani pod imionami plemiennymi. Saksonowie ze starszej Saksonii bez wątpienia byli wśród nich w dużej mierze reprezentowani, ale osobliwym faktem jest to, że w Anglii nazwa Saxon była początkowo używana tylko przez brytyjskich kronikarzy jako ogólne określenie ich wrogów, podczas gdy przybysze byli wyraźnie znani wśród nich posługując się ich plemiennymi imionami.

W różnych okresach ludzie zwani Sasami w Germanii skolonizowali inne ziemie poza Anglią. Niektórzy wyemigrowali na wschód przez Łabę do kraju Wendów i rozpoczęli proces stopniowego wchłaniania, w ramach którego lud Wendów i ich język zostały teraz całkowicie połączone z językiem niemieckim. Inni wyemigrowali na południe.

The early reference by Cæsar to a German nation he calls the Cherusci probably refers to the people afterwards called Saxons. Some German scholars identify the god of these people, called Heru or Cheru, as identical with the eponymous god of the Saxons, called Saxnot, who corresponded to the northern Tyr, or Tius, after whom our Tuesday has been named.[4] The Saxon name was at one time applied to the islands off the west coast of Schleswig, now known as the North Frisian Islands, and the country called by the later name Saxland extended from the lower course of the Elbe to the Baltic coast near Rugen. The earlier Saxony, however, from which settlers in England came was both westward and northward of the Elbe. There were some Saxons who at an early period migrated as far west as the country near the mouth of the Rhine, and it was probably from this colony that some of their descendants migrated centuries later into Transylvania, where their posterity still preserve the ancient name among the Hungarians or Magyars.

As regards the Saxons in England, it is also a singular circumstance that they were not known to the Northmen by that name, for throughout the Sagas no instance occurs in which the Northmen are said to have come into contact in England with people called Saxons.[5] One of the names by which they were known to the Scandinavians appears to have been Swæfas.

Co się tyczy Saksonów w Anglii, jest to również szczególna okoliczność, że nie byli oni znani ludziom północy pod tym imieniem, ponieważ w sagach nie ma żadnego przypadku, w którym mówi się, że ludzie północy mieli kontakt w Anglii z ludźmi zwanymi Sasami. [5] Jednym z imion, pod którymi byli znani Skandynawom, wydaje się być Swaefas.

The Saxons are not mentioned by Tacitus, who wrote about the end of the first century, but are mentioned by Ptolemy in the second century as inhabiting the country north of the Lower Elbe.[6] Wherever they may have been at first located in Germany, it is certain that people of this nation migrated to other districts from that occupied by the main body. We know of the Saxon migration to the coast of Belgium and North-Eastern France. and of the special official appointed by the Romans to protect these coasts and the south-eastern coasts of Britain. On the Continental side of the Channel there certainly were early settlements of Saxons, and it is probable there were some on the British side. These historical references show that the name is a very old one, which was used in ancient Germany for a race of people, while in England it was used both in reference to the Old Saxons and also in a wider sense by both Welsh and English chroniclers. In Germany the name was probably applied to the inhabitants of the sea-coast and water systems of the Lower Rhine, Weser, Lower Elbe and Eyder, to Low Germans on the Rhine, to Frisians and Saxons on the Elbe, and to North Frisians on the Ryder.[7]

Sasi nie są wymieniani przez Tacyta, który pisał o końcu I wieku, ale Ptolemeusz wspomina o nich w II wieku jako zamieszkujących kraj na północ od Dolnej Łaby [6]. Bez względu na to, gdzie początkowo znajdowali się w Germanii, pewne jest, że ludzie tego rodu migrowali do innych dzielnic z tych zajmowanych przez główny ich trzon. Wiemy o migracji Sasów do wybrzeży Belgii i północno-wschodniej Francji oraz o funkcji specjalnego urzędnika wyznaczonego przez Rzymian do ochrony tych wybrzeży i południowo-wschodnich wybrzeży Brytanii. Po kontynentalnej stronie Kanału z pewnością istniały wczesne osady Sasów i prawdopodobnie po stronie brytyjskiej. Te historyczne wzmianki pokazują, że nazwa ta jest bardzo stara, która była używana w starożytnej Germanii dla rodu ludzi, podczas gdy w Anglii była używana zarówno w odniesieniu do Starych Sasów, jak i w szerszym znaczeniu zarówno przez kronikarzy walijskich, jak i angielskich. W Germanii nazwa ta była prawdopodobnie stosowana do mieszkańców wybrzeży i systemów wodnych Dolnego Renu, Wezery, Dolnej Łaby i Eyderu, do Dolnych Germanów nad Renem, do Fryzów i Sasów nad Łabą oraz do północnofryzyjskich Ryderów.[7]

In considering the subject of the alliances of various nations and tribes in the Anglo-Saxon conquests, it is desirable to remember how great a part confederacies played in the wanderings and conquests of the northern races of Europe during and after the decline of the Roman Empire. The name Frank supplies a good example. This was the name of a great confederation, all the members of it agreeing in calling themselves free.[8] Hence, instead of assuming migrations (some historically improbable) to account for the Franks of France, the Franks of Franche-comte, and the Franks of Franconia, we may simply suppose them to be Franks of different divisions of the Frank confederation—i.e., people of various great tribes united under a common designation. Again, the Angli are grouped with the Varini, not only as neighbouring nations on the east coast of Schleswig, but in the matter of laws under their later names, Angles and Warings. Similarly, we read of Goths and Vandals,[9] of Frisians and Chaucians, of Goths and Burgundians, of Engles and Swæfas, of Franks and Batavians, of Wends and Saxons, of Frisians and Hunsings; and as we read of a Frank confederation, there was practically a Saxon one. In later centuries, under the general name of Danes, we are told by Henry of Huntingdon of Danes and Goths, Norwegians and Swedes, Vandals and Frisians, as the names of those people who desolated England for 230 years.[10] The later Saxon confederation is that which was opposed to Charlemagne but there was certainly an earlier alliance, or there were common expeditions of Saxons and people of other tribes acting together in the invasion of England under the Saxon name.

Rozważając temat sojuszy różnych narodów i plemion w podbojach anglosaskich, warto przypomnieć, jak wielką rolę konfederacje odegrały w wędrówkach i podbojach północnych rodów Europy podczas i po upadku Cesarstwa Rzymskiego. Dobrym przykładem jest miano Franków. Tak nazywała się wielka konfederacja, której wszyscy członkowie zgadzali się nazywać siebie wolnymi[8]. Dlatego zamiast zakładać, że migracje (niektóre historycznie nieprawdopodobne) określają Franków francuskich, Franków z Franche-comte i Franków Frankońskich, możemy po prostu przypuszczać, że są to Frankowie z różnych odłamów konfederacji frankońskiej, tj. ludzie z różnych wielkich plemion zjednoczeni pod wspólnym oznaczeniem. Ponownie Angliowie są zgrupowani z Varini, nie tylko jako sąsiednie narody na wschodnim wybrzeżu Szlezwiku, ale w kwestii praw pod ich późniejszymi nazwami, Angles and Warings. Podobnie czytamy o Gotach i Wandalach,[9] Fryzach i Chaucjanach, Gotach i Burgundach, Anglach i Swaefach, Frankach i Batawach, Wendach i Sasach, Fryzach i Hunsingach; a jak czytamy o konfederacji Franków, była to praktycznie konfederacja saksońska. W późniejszych wiekach pod ogólnym imieniem Duńczyków Henryk z Huntingdonu z Duńczyków i Gotów, Norwegów i Szwedów, Wandalów i Fryzów podaje imiona tych ludzi, którzy przez 230 lat pustoszyli Anglię[10]. Późniejsza konfederacja saksońska to ta, która była przeciwna Karolowi Wielkiemu, ale z pewnością istniał wcześniejszy sojusz, lub były wspólne wyprawy Sasów i ludzi z innych plemion działających razem w inwazji na Anglię pod nazwą Saxonów.

In view of a supposed Saxon alliance during the invasion and settlement of England, the question arises, with which nations the Saxon people who took part in the attacks on Britain could have formed a confederacy. Northward, their territory joined that of the Angles; on the north and west it touched that of the Frisians, and on the east the country of the Wendish people known as the Wilte or Wilzi. Not far from them on the west the German tribe known as the Boructarii were located, and these are the people from whom Bede tells us that some of the English in his time were known to have been derived.

Wobec rzekomego sojuszu Sasów podczas inwazji i zasiedlenia Anglii powstaje pytanie, z jakimi rodami ród saski, który brał udział w atakach na Wielką Brytanię, mógł utworzyć konfederację. Na północy ich terytorium dołączyło do terytorium Anglów; na północy i zachodzie dotknęła kraju Fryzów, a na wschodzie kraju Wendów, znanego jako Wilte lub Wilzi. Niedaleko od nich na zachodzie znajdowało się germańskie plemię znane jako Boructarii, i to są ludzie, o których Bede mówi nam, że niektórzy Anglicy w jego czasach byli znani z pochodzenia od nich.

During the folk-wanderings some of the Suevi migrated to Swabia, in South Germany, and these people, called by the Scandian nations the Swæfas, were practically of the same race as the Saxons, and their name is sometimes used for Saxon. The Angarians, or Men of Engern, also were a tribe of the Old Saxons. Later on, we find the name Ostphalia used for the Saxon country lying east of Engern, now called Hanover, and Westphalia for the country lying west of this district. Among the Saxons there were tribal divisions or clans, such as that of the people known as the Ymbre, or Ambrones, and the pagus of the Bucki among the Engern people.[11]

Podczas wędrówek ludów część Swebów wyemigrowała do Szwabii w południowej Germanii, a ludzie ci, zwani przez narody skandynawskie Swaefami, byli praktycznie tej samej rasy co Sasi, a ich nazwa jest czasami używana dla Sasów. Angarianie, czyli ludzie z Engernu, również byli plemieniem Starych Sasów. Później odnajdujemy nazwę Ostfalia używaną dla kraju saskiego położonego na wschód od Engern, obecnie zwanego Hanowerem, a Westfalia dla kraju położonego na zachód od tego okręgu. Wśród Sasów istniały podziały plemienne lub klany, takie jak lud znany jako Ymbre lub Ambrones, a pagus Bucki wśród ludu Engern.[11]

This pagus of the Old Saxons has probably left its name not only in that of Buccingaham, now Buckingham, but also in other English counties. In Norfolk we find the Anglo-Saxon names Buchestuna, Buckenham. and others. In Northampton the Domesday names Buchebi, Buchenho, Buchestone, and others, occur. In Huntingdonshire, similarly,we find Buchesunorth, Buchesworth, and Buchelone; in Yorkshire Bucktorp, in Nottinghamshire Buchetone, in Devon Buchesworth and Bucheside, all apparently named after settlers called Buche. If a settler was of the Bucki tribe, it is easy to see how he could be known to his neighbours by this name.

The Buccinobantes, mentioned by Ammianus,[12] were a German tribe, from which settlers were introduced into Britain as Roman colonists before the end of Roman rule in Britain.[13] The results of research render it more and more probable that Teutonic people under the Saxon name were gradually gaining a footing in the island before the period at which the chief invasions are said to have commenced. In the intestine wars that went on in the fifth century the presence of people of Teutonic descent among the Britons might naturally have led to Teutonic allies having been called in, or to have facilitated their conquests.[14]

Wspomniani przez Ammianusa Buccinobantes[12] byli plemieniem Germanii, z którego osadnicy zostali sprowadzeni do Wielkiej Brytanii jako koloniści rzymscy przed końcem rządów rzymskich w Wielkiej Brytanii[13]. Wyniki badań coraz bardziej uprawdopodobniają, że przed okresem, w którym miały rozpocząć się główne najazdy, na wyspie stopniowo osiedlali się Teutoni (krzyżowcy / krzyżacy) o imieniu Sasi. W wojnach, które miały miejsce w V wieku, obecność ludu „krzyżackiego” wśród Brytyjczyków mogła w naturalny sposób doprowadzić do wezwania sojuszników krzyżackich (teutońskich) lub ułatwić im podboje.[14]

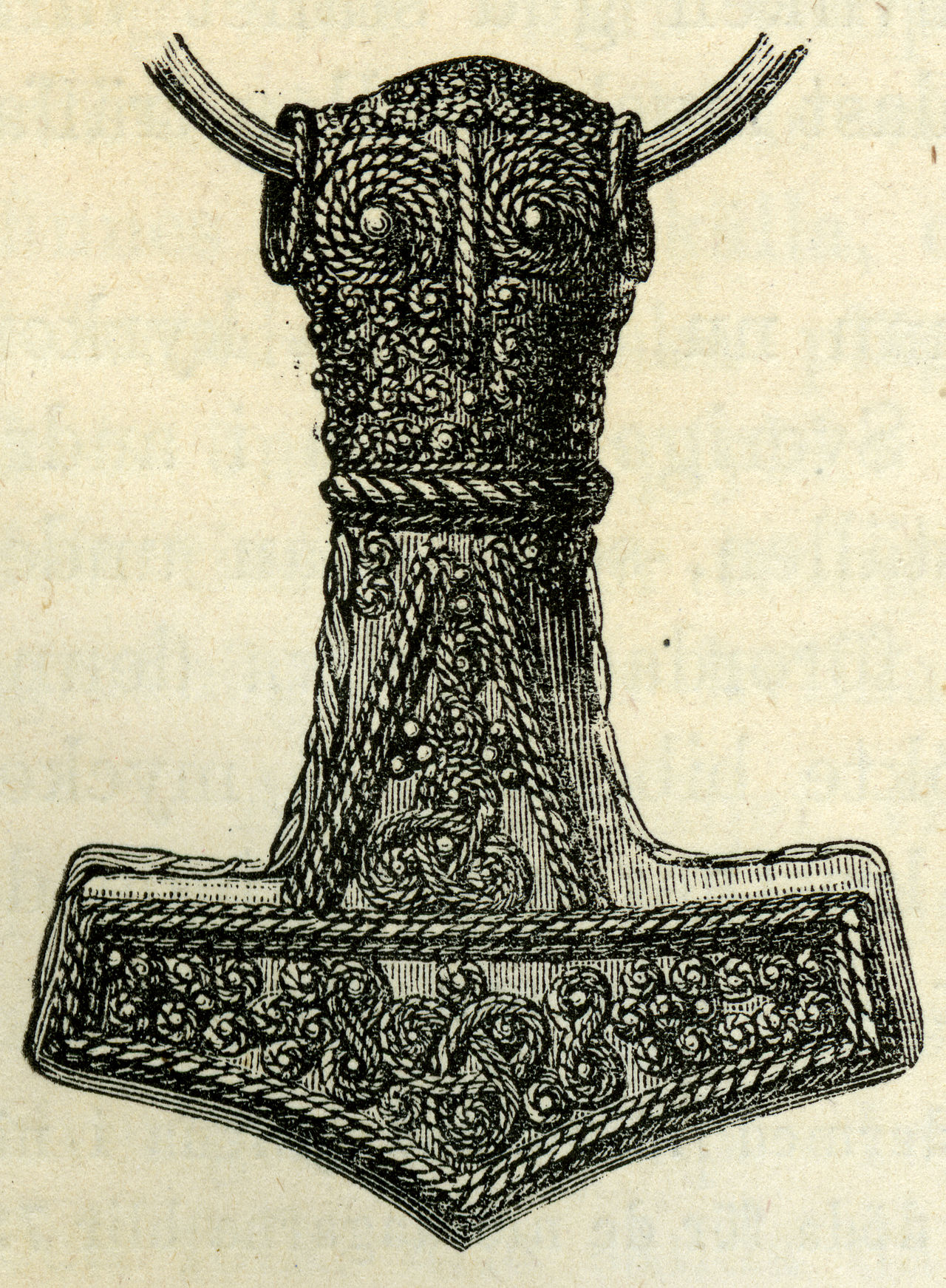

Ptolemy is the first writer who mentions the Saxons, and he states that they occupied the country which is now Holstein; but between his time and the invasion of Britain they probably shifted more to the south-west. to the region of Hanover and Westphalia, some probably remaining on the north bank of the Elbe. He tells us of a people called the Pharadini, a name resembling Varini or Warings, allies of the Angles, who lay next to the Saxons. He mentions also the three islands of the Saxons, which are probably those known now as the North Frisian Islands, north of the coast where the Saxons he mentioned are said to have lived. This is the country that within historic time has been, and still is in part, occupied by the North Frisians. The origin of the name Saxon has been a puzzle to philologists, and Latham has summed up the evidence in favour of its being a native name as indecisive. There was certainly a god known in Teutonic mythology as Saxnote or Saxneat, but whether the name Saxon was derived from the god, or the god derived his name from the people who reverenced him, is uncertain. We find this Saxnote mentioned in the pedigree of the early Kings of Essex. Thunar, Woden, and Saxnote are also mentioned as the gods whom the early Christians in Germany had to declare publicly that they would forsake,[15] and the identity of Saxnote with Tiu, Tius, or Tyr, is apparent from this as well as from other evidence.

Ptolemeusz jest pierwszym pisarzem, który wspomina Sasów i twierdzi, że okupowali oni kraj, który jest teraz Holsteinem; ale między jego czasem a inwazją na Wielką Brytanię prawdopodobnie przesunęli się bardziej na południowy zachód, do regionu Hanoweru i Westfalii, niektórzy prawdopodobnie pozostają na północnym brzegu Łaby. Opowiada nam o narodzie zwanym Pharadini, imieniem przypominającym Varini lub Warings, sojusznikami Anglów [Anglowie, Angli = Ugli (co sie tyczy Kątów, słowiańskich / drackich=trackich Ugłów – Kątynów, Kotynów) CB], którzy leżą obok Saksonów. Wspomina również o trzech wyspach Sasów, które prawdopodobnie są obecnie znane jako Wyspy Północnofryzyjskie, na północ od wybrzeża, gdzie podobno mieszkali wspomniani przez niego Sasi. Jest to kraj, który w czasach historycznych był i nadal jest częściowo okupowany przez Fryzów Północnych. Pochodzenie nazwy Saxon było dla filologów zagadką, a Latham podsumował dowody na to, że jest to nazwa rodzima, jako niezdecydowane. Z pewnością istniał bóg znany w mitologii krzyżackiej (teutońskiej) jako Saxnote lub Saxneat, ale czy imię Saxon wywodzi się od boga, czy też bóg wywodzi swoje imię od ludzi, którzy go czcili, jest niepewne. Znajdujemy tę saksońską wzmiankę w rodowodzie wczesnych królów Essex. Thunar. Woden i Saxnote są również wymieniani jako bogowie, których pierwsi chrześcijanie w Niemczech musieli publicznie ogłosić, że porzucą[15], a tożsamość Saxnote z Tiu, Tiusem lub Tyrem wynika jasno z tego, jak również z z innych dowodów.

During the Roman period a large number of Germans, fleeing from the southeast, arrived in the plains of Belgium, and the names Flamand, Flemish, and Flanders were derived from these refugees, who in some accounts are described as Saxons, and the coast they occupied as the well-known litus Saxonicum, or Saxon shore.[16] This is an important consideration in reference to the subsequent settlement of England, for it shows that there were people called Saxons before the actual invasion occurred, located on a coast much nearer to this country than that along the Elbe. In the time of Charlemagne the lower course of the Elbe divided the Saxons into two chief branches, and those to the north of it were called Nordalbingians, or people north of the Elbe, which is the position where the Saxons of Ptolemy’s time are said to have been located. One of the neighbouring races to the Saxons in the first half of the sixth century in North Germany was the Longobards or Lombards. Their great migration to the south under their King Alboin, and their subsequent invasion of Italy, occurred about the middle of the sixth century. This was about the time when the Saxons were defeated with great slaughter near the Weser. by Hlothaire, King of the Franks. Some of the survivors are said to have accompanied the Lombards, and others in all probability helped to swell the number of emigrants into England. It is probable that after this time they became more or less scattered to the south and across the sea, and in Germany the modem name Saxony along the upper course of the Elbe is a surviving name of a larger Saxony. The Germans have an ancient proverb which is still in use: ‘There are Saxons wherever pretty girls grow out of trees’[17]—perhaps a reference to the fair complexion of the old Saxon race, and to its wide dispersion.

W okresie rzymskim duża liczba Germanów, uciekając z południowego wschodu, przybyła na równiny belgijskie, a nazwy Flamand, Flamand i Flanders pochodziły od tych uchodźców, którzy w niektórych relacjach są określani jako Sasi, a nazwy wybrzeża zajętych jako dobrze znany litus Saxonicum, czyli brzeg saski.[16] Jest to ważna uwaga w odniesieniu do późniejszego osadnictwa Anglii, ponieważ pokazuje, że przed najazdem istniały ludy zwane Sasami, położone na wybrzeżu znacznie bliżej tego kraju niż wzdłuż Łaby. W czasach Karola Wielkiego dolny bieg Łaby dzielił Sasów na dwie główne gałęzie, a tych na północ od niej nazywano Nordalbingami, czyli ludami na północ od Łaby, na której podobno Sasi z czasów Ptolemeusza zostali zlokalizowani. Jedną z ras sąsiadujących z Sasami w pierwszej połowie VI wieku w północnej Germanii byli Longobardowie lub Lombardowie. Ich wielka migracja na południe pod panowaniem króla Alboina i późniejsza inwazja na Romę miały miejsce około połowy VI wieku. Było to mniej więcej w czasie, gdy Sasi zostali pokonani wielką rzezią w pobliżu Wezery przez Hlothaire’a, króla Franków. Niektórzy ocaleni podobno towarzyszyli Longobardom, a inni najprawdopodobniej przyczynili się do zwiększenia liczby emigrantów do Anglii. Jest prawdopodobne, że po tym czasie rozproszyły się one mniej więcej na południe i za morze, a w Germanii współczesna nazwa Saksonia w górnym biegu Łaby jest zachowaną nazwą Wielkiej Saksonii. Niemcy mają starożytne przysłowie, które wciąż jest w użyciu: „Sasi są wszędzie tam, gdzie jasnowłose dziewczęta rodzą się na pniu”[17] – być może jest to nawiązanie do jasnej karnacji starej rasy saskiej i jej szerokiego rozproszenia.

The circumstance that the maritime inhabitants of the German coasts were known as Saxons before the fall of the Roman Empire shows that the name was applied to a seafaring people, and under it at that time the early Frislans were probably included, The later information we obtain concerning the identity of the wergelds, or payments for injuries, that prevailed among both of these nations supports this view. The Saxon as well as the Frisian wergeld to be paid to the kindred in the case of a man being killed was 160 solidi, or shillings.[18]

Okoliczność, że nadmorscy mieszkańcy wybrzeży Germanii znani byli jako Sasi przed upadkiem Cesarstwa Rzymskiego, wskazuje, że nazwa ta była stosowana do ludu żeglarzy, a pod nią w tym czasie byli prawdopodobnie uwzględnieni wcześni Frislanowie, dotyczy też ona tożsamości wergeldów, czy opłat za szkody, które panowały wśród obu tych narodów. Popiera ten pogląd fakt że Wergeld saksoński i fryzyjski płacić miał krewnym w przypadku zabicia człowieka 160 solidi, czyli szylingów.[18]

There are two sources, so far as our own island is concerned, whence we may derive historical information concerning the conquest and settlement of Eng1and—viz., from the earliest English writers and from the earliest Welsh writers. Bede is the earliest author of English birth, and Nennius, to whom the ‘Historia Britonum’ is ascribed, is the earliest Welsh author. The veracity of the ‘Historia Britonum’ is not seriously doubted—at least, the book under that name of which Nennius is the reputed author. Its date is probably about the middle of the eighth century, and we have no reason to suppose that the learning to be found at that time in the English monasteries was superior to that in the Welsh. Nennius lived in the same century as Bede. but wrote about half a century later. His information is of value as pointing to a large number of German tribes under the general name of Saxons, rather than people of one nationality only, having taken part in the invasion and settlement of England. Nennius tells us of the struggles which went on between the Britons and the invaders. He says: ‘The more the Saxons were vanquished, the more they sought for new supplies of Saxons from Germany, so that Kings, commanders, and military bands were invited over from almost every province. And this practice they continued till the reign of Inda, who was the son of Eoppa; he of the Saxon race was the first King in Bernicia, and in Cær Ebranc (York).’[19]

Jeśli chodzi o naszą wyspę, istnieją dwa źródła, z których możemy czerpać informacje historyczne dotyczące podboju i osadnictwa w Anglii — mianowicie od najwcześniejszych pisarzy angielskich i od najwcześniejszych pisarzy walijskich. Bede jest najwcześniejszym autorem pochodzenia angielskiego, a Nenniusz, któremu przypisuje się „Historia Britonum”, jest najwcześniejszym autorem walijskim. Nie ma żadnych poważnych wątpliwości co do prawdziwości „Historii Britonum” – przynajmniej książki pod tym tytułem, której znanym autorem jest Nennius. Jego data prawdopodobnie przypada na połowę VIII wieku i nie mamy powodu przypuszczać, że nauka, którą można było wówczas znaleźć w klasztorach angielskich, była lepsza niż w walijskim. Nenniusz żył w tym samym stuleciu co Beda, ale pisał około pół wieku później. Jego informacje są cenne, ponieważ wskazują na dużą liczbę plemion germańskich pod ogólną nazwą Sasów, a nie ludzi tylko jednej narodowości, którzy brali udział w inwazji i zasiedleniu Anglii. Nenniusz opowiada nam o walkach, jakie toczyły się między Brytyjczykami a najeźdźcami. Mówi: „Im bardziej Sasi byli pokonani, tym bardziej szukali nowych w3zmocnień Sasami z Gremanii, tak że królowie, dowódcy i bandy wojskowe były zapraszane z prawie każdej prowincji. I tę praktykę kontynuowali aż do panowania Indy, syna Eoppy; on z rasy saskiej był pierwszym królem w Bernicia oraz w Cær Ebranc (York).”[19]

In reference to Cæsar’s account of German tribes, it is significant that he mentions a tribe or nation called the Cherusci as the head of a great confederation. It is of interest to note also that, as long as we find the name Cherusci used, Saxons are not mentioned, but as soon as the Cherusci disappear by name the Saxons appear, and these in a later time also formed a great confederacy. The name Gewissas, which was that by which the West Saxons were known, included Jutes—i.e.., in all probability, Goths, Frisians, Wends, and possibly people of other tribes, as well as those from the Saxon fatherland.

W nawiązaniu do relacji Cezara o plemionach germańskich, znamienne jest, że jako naczelny szczep wielkiej konfederacji wymienia on plemię lub naród zwany Cheruskami. Warto również zauważyć, że dopóki znajdujemy używane miano Cherusci, Sasi nie są wymieniani, ale gdy tylko Cheruscy znikają z nazwy, pojawiają się Sasi, którzy w późniejszym czasie również utworzyli wielką konfederację. Nazwa Gewissas, pod którą znano Sasów Zachodnich, obejmowała Jutów, tj. według wszelkiego prawdopodobieństwa Gotów, Fryzów, Wendów i prawdopodobnie ludzi z innych plemion, a także z ojczyzny saskiej.

The Saxons of England were converted to Christianity before those of the Continent, and we derive some indirect information of the racial affinities between these peoples from the accounts of the early missionary zeal of priests from England among the old Saxons. Two of these, who are said to have been Anglians, went into Saxony to convert the people, and were murdered there; but in after-centuries their names were held in high reverence, and are still honoured in Westphalia. We can scarcely think that they would have set forth on such a missionary expedition unless their dialect or language had so much in common as to enable them as Anglians from England to make themselves easily understood to these old Saxons.

Sasi z Anglii przeszli na chrześcijaństwo przed tymi z Kontynentu, a niektóre pośrednie informacje na temat pokrewieństwa rasowego między tymi ludami czerpiemy z relacji o wczesnej gorliwości misyjnej księży z Anglii wśród starych Saksonów. Dwóch z nich, o których mówi się, że byli Anglikami, pojechało do Saksonii, aby nawrócić ludzi i tam zostało zamordowanych; ale w późniejszych stuleciach ich imiona otaczano wielką czcią i nadal są czczone w Westfalii. Nie możemy myśleć, że wyruszyliby na taką wyprawę misyjną, gdyby ich dialekt lub język nie miały ze sobą tyle wspólnego, że jako Anglicy z Anglii mogli być łatwo zrozumiani przez tych miejscowych Saksonów.

The question who were the true Saxons—i.e., the Saxons specifically so called in Germany—has been much discussed. The name may not have been a native one, but have been fixed on them by others, in which case, as Beddoe says, it is easier to believe that the Frisians were often included under it.[20] They may have been, and probably were, a great martial and aggressive tribe, which spread from the country along the Elbe over the country of the Weser, after conquering its previous inhabitants, the Boructarii, or Bructers. Such a migration best accounts for the later appearance of Saxons in the region which the Old English called Old Saxony, and erroneously looked upon as their old home, because their kindred had come to occupy it since their separation. The Saxonia of the ninth century included Hanover, Westphalia, and Holstein, as opposed to Friesland, Schleswig. the Middle Rhine provinces, and the parts east of the Elbe, which were Frisian, Danish, Frank, and Slavonic respectively.[21] Among the Saxons of the country north of the Elbe were the people of Stormaria, whose name survived in that of the river Stoer, a boundary of it, and perhaps also in one or more of the rivers Stour, where some of the Stormarii settled in England.

William of Malmesbury, who wrote early in the twelfth century, tells us that the ancient country called Germany was divided into many provinces, and took its name from germinating so many men. This may be a fanciful derivation, but he goes on to say that, ‘as the pruner cuts off the more luxuriant branches of the tree to impart a livelier vigour to the remainder, so the inhabitants of this country assist their common parent by the expulsion of a part of their members, lest she should perish by giving sustenance to too numerous an offspring; but in order to obviate the discontent, they cast lots who shall be compelled to migrate. Hence the men of this country made a virtue of necessity, and when driven from their native soil have gained foreign settlements by force of arms’[22] He gives as instances of this the Vandals, Goths, Lombards. and Normans. There is other evidence of the prevalence of this custom. The story of Hengist and Horsa is one of the same kind, The custom appears to have been common to many different nations or tribes in the northern parts of Europe, and points, consequently, to the pressure of an increasing population and to diversity of origin among the settlers known as Saxons, Angles, and Jutes in England.

Wilhelm z Malmesbury, który pisał na początku XII wieku, mówi nam, że starożytny kraj zwany Germanią był podzielony na wiele prowincji i wziął swoją nazwę od „kiełkowania” (rozrostu CB) tak wielu ludzi. Może to być wymyślone pochodzenie, ale dalej mówi, że „jak sekator odcina bardziej bujne gałęzie drzewa, aby dodać żywszego wigoru reszcie, tak mieszkańcy tego kraju pomagają wspólnemu rodzicowi w wydaleniu części ich członków, aby wspólnota nie zginęła, dając utrzymanie zbyt licznemu potomstwu; ale aby uniknąć niezadowolenia, rzucają losy, którzy będą zmuszeni do wędrówki. Dlatego ludzie tego kraju uczynili cnotę z konieczności, a wygnani ze swojej ojczystej ziemi siłą orężną zdobywali obce osady”[22]. Jako przykład podaje Wandalów, Gotów, Longobardów i Normanów. Istnieją inne dowody na powszechność tego zwyczaju. Historia Hengista i Horsy podaje takie same fakty. Wydaje się, że zwyczaj ten był wspólny dla wielu różnych narodów lub plemion w północnej części Europy i wskazuje w konsekwencji na presję rosnącej populacji i różnorodność pochodzenia wśród osadników znanych jako Sasi, Anglicy i Jutowie w Anglii.

The invasions of England at different periods between the fifth and tenth centuries, and the settlement of the country as it was until the end of the Anglo-Saxon period, were invasions and settlements of different tribes. It is necessary to emphasize this. Bede’s list of nations, among others, from whom the Anglo-Saxon people in his day were known to have descended is considerably longer and more varied than that of Jutes, Saxons, and Angles. During the centuries that followed his time people of other races found new homes here, some by conquest, as in the case of Norse and Danes, and others by peaceful means, as in the time of King Alfred, when, as Asser tells us, Franks, Frisians, Gauls, Pagans, Britons, Scots, and Armoricans placed themselves under his government.[23] As Alfred made no Continental conquests, the Franks, Gauls, and Frisians must have become peaceful settlers in England, and as the only pagans in his time in Europe were the northern nations—Danes, Norse, Swedes, and Wends—some of these must also have peacefully settled in his country, as we know that Danes and Norse did largely during this as well as a later period. Men of many different races must have been among the ancestors of both the earlier and later Anglo-Saxon people.

Najazdy na Anglię w różnych okresach między piątym a dziesiątym wiekiem oraz zasiedlanie kraju aż do końca okresu anglosaskiego były najazdami i osadnictwem różnych plemion. Trzeba to podkreślić. Lista Bedy, między innymi narodów, z których wywodzili się Anglosasi w jego czasach, jest znacznie dłuższa i bardziej zróżnicowana niż lista Jutów, Sasów i Anglów. W następnych stuleciach ludzie innych ras znaleźli tu nowe domy, jedni drogą podboju, jak w przypadku Nordów i Duńczyków, a inni pokojowymi środkami, jak za czasów króla Alfreda, kiedy, jak mówi nam Asser, Frankowie, Fryzowie, Galowie, Poganie, Brytyjczycy, Szkoci i Armorykanie oddali się pod jego rządy.[23] Ponieważ Alfred nie dokonał żadnych podbojów kontynentalnych, Frankowie, Galowie i Fryzowie musieli stać się pokojowymi osadnikami w Anglii, a ponieważ jedynymi poganami w jego czasach w Europie były narody północne – Duńczycy, Nordowie, Szwedzi i Wendowie – niektóre z nich musiały również pokojowo osiedlić się w swoim kraju, ponieważ wiemy, że Duńczycy i Nordowie zrobili to głównie w tym, jak i późniejszym okresie. Mężczyźni wielu różnych ras musieli należeć do przodków zarówno wcześniejszego, jak i późniejszego ludu anglosaskiego.

In the eighth and ninth centuries three kingdoms in England bore the Saxon name, as mentioned by Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle—viz., Essex, Sussex, and Wessex—and one province, Middlesex. As will be seen when considering the evidence relating to the settlers in various parts of England, it does not follow that these several parts of our country which were called after the Saxon name were colonized by people known as Saxons in Germany. The customs that prevailed in these parts of England were different in many localities. The relics of the Anglo-Saxon period that have been discovered in these districts present also some distinctive features. It is certain from the customs that prevailed, some of which have survived, from the remains found, from the old place-names, and from the variations in the shape of the skulls discovered, that the people of the Saxon kingdoms of England could not have been people of one race. The anthropological evidence which has been collected by Beddoe[24] and others confirms this, for the skulls taken from Saxon cemeteries in England exhibit differences in the shape of the head which could not have resulted from accidental variations in the head-form of people all of one uniform race or descent.[25] The typical Saxon skull was dolichocephalic, or long, the breadth not exceeding four-fifths of the length, like those of all the nations of the Gothic stock. Goths, Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, Angles, and Saxons among the ancient nations all had this general head-form, as shown by the remains of these several races which have been found, and from the head-form of the modern nations descended from them; but among these long-headed people there were some with variations in the skull and a few with broad skulls.

W ósmym i dziewiątym wieku trzy królestwa w Anglii nosiły nazwę saską, jak wspomina Bede i Anglo-Saxon Chronicle — mianowicie Essex, Sussex i Wessex — oraz jedna prowincja — Middlesex. Jak zobaczymy, rozważając dowody odnoszące się do osadników w różnych częściach Anglii, nie wynika z tego, że te kilka części naszego kraju, które nazwano imieniem saskim, zostało skolonizowanych przez ludzi znanych jako Sasi w Germanii. Obyczaje panujące w tych częściach Anglii w wielu miejscowościach były odmienne. Odkryte na tych terenach relikty okresu anglosaskiego mają również pewne charakterystyczne cechy. Z obyczajów, które panowały, z których niektóre przetrwały, ze znalezionych szczątków, ze starych nazw miejscowości i ze zmian kształtu czaszek, wynika, że ludność saksońskich królestw Anglii nie mogła byli ludźmi jednej rasy. Potwierdzają to dowody antropologiczne zebrane przez Beddoe[24] i innych, gdyż czaszki pobrane z saksońskich cmentarzy w Anglii wykazują różnice w kształcie głowy, które nie mogły wynikać z przypadkowych różnic w kształcie głowy wszystkich ludzi jednej jednolitej rasy lub pochodzenia.[25] Typowa saksońska czaszka była dolichocefaliczna lub długa, a jej szerokość nie przekraczała czterech piątych długości, jak u wszystkich narodów rasy gotyckiej. Goci, Norwegowie, Szwedzi, Duńczycy, Anglicy i Sasi wśród starożytnych narodów wszyscy mieli tę ogólną formę głowy, jak pokazują szczątki kopalne ludzi tych kilku ras, które zostały znalezione, i z kształtu głowy współczesnych narodów wywodzących się od im; ale wśród tych długogłowych ludzi byli niektórzy z odmianami czaszki i niektórzy z szerokimi czaszkami.

The Saxons must have been nearly allied to some of the Angles. This is shown by the probability that the so-called Saxons are located by Ptolemy in the country north of the Elbe, which by other early writers is assigned mainly to the Angles. His references to the tribe or nation known as the Suevi point to the same conclusion, the Suevi-Angli mentioned by him[26] being apparently another name for the people of the country which, according to others, was occupied by Saxons, and these Suevi or Suabi are mentioned as at Saxon pagus in early German records.[27] The Scandian peninsula, so remarkable for early emigration, was probably the original home at some very remote period of the ancestors of the nations known in later centuries as Saxons, Suevi, and Angles. The racial characters of all the Teutonic tribes of North Germany, as of their modern representatives, were fair hair and eyes. and heads of the dolichocephalic shape. These characters differentiated the northern tribes of Germany from the more ancient occupants of Central Europe, as at the present time they distinguish them from the darker-haired South Germans of Bavaria and Austria, who have broader skulls than those of the north. The skulls which are found in ancient burial-places in Germany of the same age as the Anglo-Saxon period are of two main types—viz., the dolichocephalic or long, and the brachycephalic or broad. In the old burial-places at Bremen, from which 103 examples were obtained, only 5 typical broad skulls were found, against 72 typical long skulls and 26 which were classed by Gildemeister as intermediate in form.[28] These 26 he regarded as Frisian, and gave them the name Batavian. In the South of Germany graves of the same age yield a majority of broad skulls, which closely correspond to those of the peasantry of the present time in the same parts of the country. From this it may be inferred that during the period of the English settlement people with long skulls were in a great majority in North Germany, and people with broad skulls in a majority in the southern parts of that country, certainly in these districts south of Thuringia. Bede tells us that the people of England were descended from many tribes, and Nennius says that Saxons came into England from almost every province in Germany. Unless we are to entirely discredit such statements, the probability that some of the settlers whom Nennius calls Saxons may have been broad-headed is great. That various tribal people under the Saxon name took part in the invasion and settlement of England is probable from many circumstances, and, among others, the minor variations in the skulls found in Anglo-Saxon graves corresponding to the minor variations found to exist also among the skulls discovered at Bremen. Of these latter Beddoe says: ‘There are small differences which may have been tribal.’[29] The same author remarks also of these Bremen skulls, that there are differences in the degree of development of the superciliary ridges which may have been more tribal than individual.[30]

Of 100 skulls of the Anglo—Saxon period actually found in England, and whose dimensions were tabulated by Beddoe, the following variations were found, the percentage of the breadth in comparison with the length being expressed by the indices:[31]

Spośród 100 czaszek z okresu anglosaskiego faktycznie znalezionych w Anglii, których wymiary zostały zestawione przez Beddoe’a, znaleziono następujące różnice, przy czym procent szerokości w porównaniu z długością był wyrażony przez wskaźniki:[31]

From this table it can be seen that 8 of the 100 have a breadth very nearly or quite equal to four-fifths of their 1ength—i.e., they are the remains of people of a different race from the typical Anglo-Saxon.

Z tej tabeli widać, że 8 na 100 ma szerokość prawie lub całkiem równą czterem piątym ich długości – tj. są to szczątki ludzi innej rasy niż typowy anglosaski.

The typical Saxon skull is believed to have been similar to that known as the ‘grave-row’ skull on the Continent, from the manner in which the bones were found laid in rows. Thcse occur numerously in Saxon burial-places in the Old Saxon and Frisian country, their mean index being about 75—i.e., they are long skulls.

Uważa się, że typowa saksońska czaszka była podobna do czaszek znanych na kontynencie z „grobów rzędowych”, nazwanych tak ze względu na sposób, w jaki kości zostały znalezione ułożone w rzędach. Występują one licznie w grobowcach saskich w kraju starosaksońskim i fryzyjskim, ich średni indeks wynosi około 75, tj. są to długie czaszki.

The variation in the skulls from Anglo-Saxon graves in England, as will be seen from the table, is very considerable, but the majority have an index from 73 to 78–i.e., they resemble in this respect those commonly found in the old burial—places of North Germany. The variations have been attributed by some writers to the racial mixture of Saxons with the conquered Britons.[32] Since, however, similar variations are seen in skulls obtained from the graves at Bremen and other parts of North Germany, it is probable that the so-called Saxons were not a people of a homogeneous race, but comprised tribal people who had variations in head-form, a small percentage being even broad-headed. The migration of such people into England among other Saxons would explain the variations found in the Anglo-Saxon head-form, and, moreover, help us to explain variations in custom that are known to have existed within the so-called Saxon kingdoms of England.

Zróżnicowanie czaszek z grobów anglosaskich w Anglii, jak widać z tabeli, jest bardzo duże, ale większość ma indeks od 73 do 78 – tj. przypominają pod tym względem te powszechnie spotykane w dawnym pochówku. — z miejsc w północnej Germanii. Różnice zostały przypisywane przez niektórych pisarzy mieszance rasowej Sasów z podbitymi Brytyjczykami.[32] Ponieważ jednak podobne odmiany są widoczne w czaszkach uzyskanych z grobów w Bremie i innych częściach północnych Niemiec, prawdopodobne jest, że tak zwani Sasi nie byli ludem jednorodnej rasy, ale składali się z plemion, które miały różne głowy -forma ta, w małym procencie jest nawet szerokogłowa. Migracja takich ludzi do Anglii, wśród innych Sasów, wyjaśniłaby różnice występujące w anglosaskiej formie głowy, a ponadto pomogłaby nam wyjaśnić różnice w zwyczajach, o których wiadomo, że istniały w tak zwanych saksońskich królestwach Anglii.

RUGIANS, WENDS, AND TRIBAL SLAVONIC SETTLERS

RUGIANIE, WENDOWIE I PLEMIONA SŁOWIAŃSKICH OSIEDLEŃCÓW

The name Wends was given by the old Teutonic nations of Germany to those Slavonic tribes who were located in the countries east of the Elbe and south of the Baltic Sea. It is the same as the older name used by Ptolemy,[1] who says that ‘the Wenedæ are established along the whole of the Wendish Gulf.’ Tacitus also mentions the Venedi. There can, therefore, be no doubt that these people were seated on the coast of Mecklenburg and Pomerania before the time of the Anglo-Saxon settlement. That there were some differences in race between the Wends of various tribes is probable from the existence of such large tribes among them as the Wiltzi and Obodriti, who in the time of Charlemagne formed opposite alliances, the former with the Saxons, the latter with the Franks. The Wends who still exist in Lower Saxony are of a dark complexion, and are of the same stock as the Sorbs or Serbs of Servia. They are Slavonic, but many tribes of Slavonic descent are fair in complexion. Procopius tells us that those Vandals who were allies of the ancient Goths were remarkable for their tall stature, pale complexion, and blonde hair.[2] It is therefore by no means improbable that the ancient Slavic tribes of the Baltic coast were distinguished by differences in complexion.

Nazwę Wends nadały dawne narody krzyżackie (teutońskie) Germanii plemionom słowiańskim, które znajdowały się w krajach na wschód od Łaby i na południe od Bałtyku. Jest to to samo, co starsza nazwa używana przez Ptolemeusza[1], który mówi, że „Wenedowie osiedlają się wzdłuż całej Zatoki Wendyjskiej”. Tacyt wspomina również Wenedów. Nie ulega więc wątpliwości, że ludność ta osiadła na wybrzeżu Meklemburgii i Pomorza jeszcze przed osadnictwem anglosaskim. To, że istniały pewne różnice rasowe między Wendami różnych plemion, wynika prawdopodobnie z istnienia wśród nich tak dużych plemion, jak Wiltzi i Obodriti, którzy w czasach Karola Wielkiego zawierali przeciwstawne sojusze, pierwsze z Sasami, drugie z Frankami. Wendowie, którzy wciąż żyją w Dolnej Saksonii, mają ciemną karnację i są tego samego pochodzenia co Serbowie Serbscy. Są Słowianami, ale wiele plemion pochodzenia słowiańskiego ma jasną cerę. Prokopiusz mówi nam, że ci Wandale, którzy byli sojusznikami starożytnych Gotów, wyróżniali się wysokim wzrostem, bladą cerą i blond włosami.[2] Nie jest więc nieprawdopodobne, że starożytne plemiona słowiańskie z wybrzeża Bałtyku wyróżniały się różnicami w karnacji.

As the identification of Vandal or Wendish settlers with various parts of England is new, or almost so, it will be desirable to state the evidence of their connection with the origin of the Anglo-Saxon race more fully than would otherwise have been necessary.

The Vandals are commonly thought to have been a nation of Teutonic descent like the Goths, but there is certain evidence that the later Vandals or Wends were Slavonic, and there is no reason to doubt that these later Vandals were descended from some of the earlier. Tacitus mentions the Vandals as a group of German nations, the name being used in a wide sense, as British is at the present time. The most important reason for considering the early Vandals to be Teutonic is that the names of their leaders are almost exclusively Teutonic, as Gonderic, Genseric, etc.[3] This reason would be valid if there were nothing else to set against it. Leaders of a more advanced race, however, have led the forces of less advanced allies in all ages, and the Goths were a more advanced race than the Vandals, whom they conquered, and who subsequently became their firm allies. Among the collection of Anglo-Saxon relics in the British Museum axe a number of Vandal ornaments from North Africa, placed there for comparison with those of the Anglo-Saxon period. These are apparently rough imitations of those of the same age found in Scandinavia and in England—i.e., imitations of Gothic work.

Powszechnie uważa się, że Wandalowie byli narodem pochodzenia krzyżackiego (teutońskiego), podobnie jak Goci, ale istnieją pewne dowody na to, że późniejsi Wandalowie lub Wendowie byli Słowianami i nie ma powodu wątpić, że ci późniejsi Wandalowie wywodzili się od niektórych z wcześniejszych. Tacyt wymienia Wandalów jako grupę narodów germańskich, których nazwa jest używana w szerokim znaczeniu, podobnie jak obecnie Brytyjczycy. Najważniejszym powodem uznania wczesnych Wandalów za teutońskich jest to, że imiona ich przywódców są prawie wyłącznie teutońskie, jak Gonderic, Genseric itp.[3] (To oczywista nieprawda etymologiczna CB!!!)Ten powód byłby słuszny, gdyby nie było niczego innego, co mogłoby mu się przeciwstawić. Jednakże przywódcy bardziej zaawansowanej rasy przewodzili siłom mniej zaawansowanych sojuszników we wszystkich epokach, a Goci byli rasą bardziej zaawansowaną niż Wandalowie, których podbili i którzy później stali się ich mocnymi sojusznikami (??? CB).Wśród kolekcji zabytków anglosaskich toporów w British Museum znajduje się szereg ozdób wandalskich z Afryki Północnej, umieszczonych tam dla porównania z tymi z okresu anglosaskiego. Są to pozornie zgrubne imitacje tych w tym samym wieku, które można znaleźć w Skandynawii i Anglii, tj. imitacje dzieł gockich.

Of all the people in ancient Germania east of the Elbe whom Tacitus mentions as Germans, not a single Teutonic vestige remained in the time of Charlemagne. Poland and Silicia were parts of his Germania. When the Germans of Charlemagne and his successors conquered the country east of the Elbe there was neither trace nor record of any earlier Teutonic occupation.[4] Such a previous occupancy rarely occurs, as Latham has pointed out, without leaving some traces of its existence by the survival here and there of descendants of the older occupants. In Germany, east of the Elbe, no earlier inhabitants than the Slavonic have been discovered, excepting those of a very remote prehistoric age. At the dawn of German history no traces are met with of enthralled people of Teutonic descent among the Slavs east of the Elbe, and there are no traditions of such earlier occupants, while the oldest place-names are all Slavonic. If there were Germans, strictly so-called, east of the river in the time of Tacitus—i.e., long-headed tribes—their assumed displacement by the Slavs between his time and that of Charlemagne would have been the greatest and most complete of any recorded in history[5] Ethnology and history, therefore, alike point to people of Sarmatian or Slavic descent—i.e., brachycephalic tribes—as the earliest inhabitants of Eastern Germany, and indicate some misunderstanding in this respect by the commentators of Tacitus.[6] In Eastern Germany place-names survive ending in -itz, so very common in Saxony; in -zig, as Leipzig; in -a, as Jena; and in -dam, as Potsdam. All these places were named by the Slavs.[7]

Ze wszystkich ludzi w starożytnej Germanii na wschód od Łaby, których Tacyt wymienia jako Germanów, w czasach Karola Wielkiego nie pozostał ani jeden ślad teutoński. Polska i Śląsk były częścią jego Germanii. Kiedy Germanie Karola Wielkiego i jego następcy podbili kraj na wschód od Łaby, nie było ani śladu ani zapisu jakiejkolwiek wcześniejszej okupacji teutońskiej.[4] Takie wcześniejsze zasiedlenie zdarza się rzadko, jak zauważył Latham, nie pozostawiając śladów swego istnienia przez przetrwanie tu i ówdzie potomków starszych okupantów. W Niemczech, na wschód od Łaby, nie odkryto żadnych wcześniejszych mieszkańców poza Słowianami, z wyjątkiem tych z bardzo odległych czasów prehistorycznych. U zarania dziejów Niemiec nie ma śladów tego co jest ich fascynacją czyli ludności teutońskiego pochodzenia wśród Słowian na wschód od Łaby, nie ma też tradycji takich wcześniejszych okupantów, a najstarsze nazwy miejscowości są w całości słowiańskie. Gdyby w czasach Tacyta na wschód od rzeki żyli Niemcy, czyli plemiona o długich głowach, ich domniemane wysiedlenie przez Słowian między jego czasem a epoką Karola Wielkiego byłoby największe i najpełniejsze ze wszystkich zapisaną w historii migracją[5]. Etnologia i historia wskazują zatem zarówno ludność pochodzenia sarmackiego, jak i słowiańskiego, czyli plemiona brachycefaliczne, jako najwcześniejszych mieszkańców Niemiec Wschodnich i wskazują na pewne nieporozumienie w tym zakresie ze strony komentatorów Tacyta[6]. ] We wschodnich Niemczech zachowały się nazwy miejsc zakończone na -itz, tak bardzo powszechne w Saksonii; w -zig, jak Lipsk; w -a, jako Jena; i w -dam, jako Poczdam. Wszystkie te miejsca zostały nazwane przez Słowian[7].

The statement of Bede that the Rugini or Rugians were among the nations from whom the English were known to have descended was contemporary evidence of his own time. The Rugi are also mentioned by Tacitus.[8] Their name apparently remains to this day in that of Rügen Island, situated off the coast which they occupied in the time of the Roman Empire.

Oświadczenie Bedy, że Rugini lub Rugianie należeli do narodów, z których wywodzili się Anglicy, było współczesnym dowodem jego czasów. Rugi są również wspomniane przez Tacyta.[8] Ich nazwa podobno pozostaje do dziś w nazwie wyspy Rugia, położonej u wybrzeży, które zajmowali w czasach Cesarstwa Rzymskiego.

As Ptolemy tells us of the wenedæ seated on this same Baltic coast, and as they were Sarmatians or Slavs, it is clear that the Rugians must have been of that race. Some of the nations mentioned by Tacitus were, he says, of non-Germanic origin. Rügen Island was the chief place of worship for the Wendish race, the chief centre of their religion. On the east side of the peninsula of Jasmund in Rügen are the white chalk cliffs of Stubbenkammer, and on the north side of the island is the promontory of Arcona, where in the twelfth century we read of the idol Svantovit, and the temple of this Wendish god. No traces of Teutonic worship have ever been found in Rügen. They are all Slavonic. Saxo tells us at the worship of Svantovit at Arcana with the tributes brought there from all Slavonia.[9]

Jednak Ptolemeusz mówi nam o Wenedach, siedzących na tym samym wybrzeżu Bałtyku, a ponieważ byli oni Sarmatami lub Słowianami, jasne jest, że Rugianie musieli należeć do tej rasy. Niektóre z wymienionych przez Tacyta narodów były, jak mówi, pochodzenia niegermańskiego. Wyspa Rugia była głównym miejscem kultu rasy Wendów, głównym ośrodkiem ich religii. Po wschodniej stronie półwyspu Jasmund na Rugii znajdują się białe kredowe klify Stubbenkammer, a po północnej stronie wyspy znajduje się cypel Arkona, gdzie w XII wieku czytamy o bożku Svantovit i świątyni tego Wendyjskiego Boga. Na Rugii nie znaleziono żadnych śladów kultu teutońskiego. Wszystkie są słowiańskie. Saxo opowiada nam o kulcie Svantovita w Arkonie wraz z daninami wiezionymi tam z całej Sławii.[9]

The probability of some very early settlers in Britain having been Wends, and consequently that there was a Slavic element in the origin of the Old English race, is shown in another way. The settlement of large bodies of Vandals in Britain by order of the Emperor Probus is a fact recorded in Roman history. The authority is Zosimus,[10] and this settlement is said to have taken place in the latter part of the third century of our era, after a great defeat of Vandals near the Lower Rhine. They were accompanied by a horde of Burgundians, and as they were apparently on the march in search of new homes, it probably suited them as well as it suited the Romans to be transported to Britain. Unless it can be shown that the Vandal name is to be understood to mean only certain tribes of Teutonic origin, this arbitrary settlement of Vandals in Britain is the earliest record of immigrants of Slavic origin. It is not possible to ascertain the parts of the country in which they settled, but as they were known to Roman writers by the names Vinidæ and Venedi, it is possible that the Roman place-names in Britain—Vindogladia in Dorset, Vindomis in Hampshire, and others—may have been connected with their settlements. It is possible also that during the time between their arrival and that of the earliest Anglo-Saxon settlers some of their descendants may have maintained their race distinctions apart from the British people, as descendants of some of the Roman colonists apparently did in Kent.

Prawdopodobieństwo, że niektórzy bardzo wcześni osadnicy w Wielkiej Brytanii byli Wendami, a co za tym idzie, że w pochodzeniu rasy staroangielskiej był element słowiański, pokazano w inny sposób. Osiedlenie dużych grup Wandalów w Wielkiej Brytanii na polecenie cesarza Probusa jest faktem odnotowanym w historii Rzymu. Władzę sprawuje Zosimus[10], a osadzenie to miało mieć miejsce w drugiej połowie III wieku naszej ery, po wielkiej klęsce Wandalów w pobliżu Dolnego Renu. Towarzyszyła im horda Burgundów, a ponieważ najwyraźniej maszerowali w poszukiwaniu nowych domów, prawdopodobnie pasowało im to, podobnie jak Rzymianom, by przetransportować się do Brytanii. O ile nie można wykazać, że nazwa Wandalów ma oznaczać tylko niektóre plemiona pochodzenia teutońskiego, to arbitralne osadzenie Wandalów w Wielkiej Brytanii jest najwcześniejszym zapisem o imigrantach pochodzenia słowiańskiego. Nie jest możliwe ustalenie części kraju, w którym osiedlili się, ale ponieważ byli oni znani pisarzom rzymskim pod imionami Vinidæ i Venedi, możliwe jest, że rzymskie nazwy miejscowości w Brytanii — Vindogladia w Dorset, Vindomis w Hampshire i inne – mogły być związane z ich osadami. Możliwe jest również, że w okresie między ich przybyciem a przybyciem pierwszych osadników anglosaskich niektórzy z ich potomków mogli zachowywać swoją odrębność rasową z wyjątkiem Brytyjczyków, jak to najwyraźniej zrobili potomkowie niektórych rzymskich kolonistów w Kent.

The defeat of the Vandals by Probus near the Rhine occurred in A.D. 277,[11] so that their settlement in Britain was not more than two centuries before the arrival of the Jutes and Saxons. As it is probable there were some so-called Saxons already settled on the eastern coast of England, with whom those of a later date coalesced, it is not impossible that some of the Vandal settlers in Britain in the time of Probus may have preserved their distinction in race until the invasion of the Saxons, Angles, and Jutes began.

Klęska Wandalów zadana im przez Probusa w pobliżu Renu miała miejsce w 277 r. [11], więc ich osadnictwo w Wielkiej Brytanii nastąpiło nie więcej niż dwa wieki przed przybyciem Jutów i Sasów. Ponieważ jest prawdopodobne, że na wschodnim wybrzeżu Anglii osiedlili się już niektórzy tak zwani Sasi, z którymi zjednoczyli się późniejsi osadnicy, nie jest wykluczone, że niektórzy z osadników Wandali w Wielkiej Brytanii w czasach Probusa mogli zachować swoje wyróżnienie rasowe aż do rozpoczęcia inwazji Saksonów, Anglów i Jutów.

The names in the Anglo-Saxon charters which apparently marked settlements of Rugians in England are Ruanbergh and Ruwanbeorg, Dorset; Ruganbeorh and Ruwanbeorg, Somerset; Ruwanbeorg and Rugan dic, Wilts; Rugebeorge, in Kent; and Ruwangoringu, Hants.[12] These will be referred to in later chapters.

The chief Old English names which appear to refer to them in Domesday Book are Ruenore in Hampshire, Ruenhala and Ruenhale in Essex, Rugehala and Rugelie in Staffordshire, Rugutune in Norfolk, and Rugarthorp in Yorkshire. Close to Ruenore, in Hampshire, is Stubbington, which may have been an imported name, as it resembles that of Stubnitz in the Isle of Rügen.

In its historical aspect the Anglo-Saxon settlement may be regarded as part of that wider migration of nations and tribes from Eastern and Northern Europe into the provinces of the Roman Empire during its decadence. In its ethnological aspect it may be regarded as a final stage in the westward European migration of people of the Germanic stock. As the history and ethnology of the Franks in Western Germany afford us a notable example of the fusion of people of the Celtic with others of the Teutonic race, so the history and ethnology of Eastern Germany afford an equally striking example of the fusion of people of Teutonic and Slavonic origins. It began at a very early period in our era, and the present irregular ethnological frontier between Germans and Slavs shows that it is still slowly going on. The eastward migration of Germans in later centuries has absorbed the Wends. The descendants of the isolated Slavonic settlers near Utrecht and in other parts of the Rhine Valley have also long been absorbed. The ethnological evidence concerning the present inhabitants of these districts and the survival of some of their old place-names, however, supports the statement of the early chroniclers concerning the immigration of Slavs into what is now Holland.

W aspekcie historycznym osadnictwo anglosaskie można uznać za część tej szerszej migracji narodów i plemion z Europy Wschodniej i Północnej do prowincji Cesarstwa Rzymskiego w okresie jego dekadencji. W aspekcie etnologicznym można ją uznać za ostatni etap migracji na zachód Europy ludności pochodzenia germańskiego. Tak jak historia i etnologia Franków w Niemczech Zachodnich dostarcza nam godnego uwagi przykładu zlania się ludu celtyckiego z innymi przedstawicielami rasy teutońskiej, tak historia i etnologia Niemiec Wschodnich dostarcza równie uderzającego przykładu zlania się ludu teutońskiego i słowiańskiego. Zaczęło się to w bardzo wczesnym okresie naszej ery, a obecna nieregularna granica etnologiczna między Niemcami a Słowianami pokazuje, że nadal powoli się rozwija. Migracja Niemców na wschód w późniejszych wiekach wchłonęła Wendów. Potomkowie odizolowanych osadników słowiańskich w pobliżu Utrechtu i w innych częściach doliny Renu również od dawna zostali wchłonięci. Etnologiczne dowody dotyczące obecnych mieszkańców tych dzielnic i przetrwania niektórych z ich dawnych nazw miejscowości potwierdzają jednak twierdzenia wczesnych kronikarzy dotyczące imigracji Słowian na tereny dzisiejszej Holandii.

The part which the ancient Wends, including Rugians, Wilte, and other Slavonic people, took in the settlement of England was, in comparison with that of the Teutonic nations and tribes, small, but yet so considerable that it has left its results. During the period of the invasion and the longer period of the settlement, the southern coasts of the Baltic Sea were certainly occupied by Slavonic people. Ptolemy, writing, as he did, about the middle of the second century of our era, mentions the Baltic by the name Venedic Gulf, and the people on its shores as Venedi or Wenedæ. He describes them as one of the great nations of Sarmatia.[13] the most ancient name of the countries occupied by Slavs, but which was replaced by that of Slavonia. Pliny, in his notice of the Baltic Sea, has the following passage: ‘People say that from this point round to the Vistula the whole country is inhabited by Sarmatians and Wends.’[14] Although he did not write from personal knowledge of the Wends, this passage is weighty evidence that they must have been located on the Baltic in his time.

Część, którą starożytni Wendowie, w tym Rugianie, Wiltzy i inne ludy słowiańskie, przyjęli w zasiedlaniu Anglii, była w porównaniu z narodami i plemionami teutońskimi niewielka, ale tak duża, że pozostawiła swoje skutki. W okresie najazdu i dłuższego okresu osadnictwa południowe wybrzeża Bałtyku były z pewnością zajęte przez ludność słowiańską. Ptolemeusz, pisząc podobnie jak on, mniej więcej w połowie drugiego wieku naszej ery, wymienia Bałtyk pod nazwą Zatoki Weneckiej, a ludzi na jego brzegach jako Wenedów lub Wenedów. Opisuje ich jako jeden z wielkich narodów Sarmacji.[13] To najstarsza nazwa krajów zajętych przez Słowian, ale zastąpiona nazwą Slawonia. Pliniusz w swoim zawiadomieniu o Bałtyku ma następujący fragment: „Ludzie mówią, że od tego miejsca w okolicach Wisły cały kraj zamieszkują Sarmaci i Wendowie”[14]; Wendowie – ten fragment jest ważnym dowodem na to, że w jego czasach musieli znajdować się na Bałtyku.

During the time of the Anglo-Saxon period the Slavs in the North of Europe extended as far westward as the Elbe and to places beyond it. On the east bank of that river were the Polabian Wends, and these were apparently a branch of the Wilte or Wiltzi. This name Wiltzi has been derived from the old Slavic word for wolf, wilk, plural wiltzi, and was given to this great tribe from their ferocious courage. The popular name Wolfmark still survives in North-East Germany, near the eastern limit of their territory. These people called themselves Welatibi, a name derived from welot, a giant, and were also known as the Hæfeldan, or Men of Havel, from being seated near the river Havel, as mentioned by King Alfred. The inhabitants of the coast near Stralsund, who were called Rugini or Rugians, and who are mentioned by Bede as one of the nations from whom the Anglo-Saxons of his time were known to have derived their origin,[15] must have been included within the general name of the Wends. As these Rugians must have been Wends, the statement of Bede is direct evidence that some of the people of England in his time were known to be of Wendish descent. This is supported by evidence of other kinds, such as the mention of settlements of people with Wendish or Vandal names in the Anglo-Saxon charters, the numerous names of places in England which have come down from a remote antiquity, and the identity of the oldest forms of such names with that of the people of this race. We read also that Edward, son of Edmund Ironside, fled after his father’s death ‘ad regnum Rugorum, quod melius vocamus Russiam.’[16] It is also supported by philological evidence. As a distinguished American philologist says: ‘The Anglo-Saxon was such a language as might be supposed would result from a fusion of Old Saxon with smaller proportions of High German, Scandinavian, and even Celtic and Slavonic elements.’[17] The migration of the Wilte from the shores of the Baltic and the foundation of a colony in the country around Utrecht is certainly historical. Bede mentions it in connection with the mission of Wilbrord. He says: ‘The Venerable Wilbrord went from Frisia to Rome, where the Pope gave him the name of Clement, and sent him back to his bishopric. Pepin gave him a place for his episcopal see in his famous castle, which, in the ancient language of those people, is called Wiltaburg—i.e., the town of the Wilti—but in the French tongue Utrecht.’[18] Venantius also tells us that the Wileti or Wiltzi, between A.D. 560-600, settled near the city of Utrecht, which from them was called Wiltaburg, and the surrounding country Wiltenia.[19] Such a migration would perhaps be made by land, and some of these Wilte may have gone further. The name of the first settlers in Wiltshire has been derived by some authors from a migration of Wilte from near Wiltaburg,[20] and the name Wilsætan appears to afford some corroboration. It is certain that Wiltshire was becoming settled in the latter half of the sixth century, and such a migration may either have come direct from the Baltic or the Elbe, or from the Wilte settlement in Holland.

It must not be supposed that there is evidence of the settlement of all Wiltshire by people descended from the Wilte, but it is not improbable that some early settlers of this time were the original Wilsætas. The Anglo-Saxon charters supply evidence of the existence in various parts of England, as will be referred to in later pages, of people called Willa or Wilte. There were tribes in England named East Willa and West Willa;[21] and such Anglo-Saxon names as Willanesham;[22] Wilburgeham, Cambridgeshire;[23] Wilburge gcmæro and Wilburge mere in Wiltshire;[24] Wilburgewel in Kent;[25] Willa-byg in Lincolnshire;[26] Wilmanford,[27] Wilmanleáhtun,[28] appear to have been derived from personal names connected with these people. I have not been able to discover that any other Continental tribe of the Anglo-Saxon period were so named, except this Wendish tribe, called by King Alfred the men of Havel, a name that apparently survived in the Domesday name Hauelingas in Essex. The Wilte or Willa, tribal name survived in England as a personal name, like the national name Scot, and is found in the thirteenth-century Hundred Rolls and other early records. In these rolls a large number of persons so named are mentioned—Wiltes occurs in seventeen entries, Wilt in eight, and Wilte in four entries. Willeman as a personal name is also mentioned.[29] The old Scando-Gothic personal name Wilia is well known.[30]

Nie należy przypuszczać, że istnieją dowody na zasiedlenie całego Wiltshire przez ludzi wywodzących się z Wilte, ale nie jest nieprawdopodobne, że niektórzy wcześni osadnicy tego czasu byli rodowitymi Wieletami. Statuty anglosaskie dostarczają dowodów na istnienie w różnych częściach Anglii, o czym będzie mowa na dalszych stronach, osób zwanych Willa lub Wilte. W Anglii istniały plemiona o nazwach East Willa i West Willa;[21] i takie anglosaskie nazwy jak Willanesham;[22] Wilburgeham, Cambridgeshire;[23] Wilburge gcmæro i Wilburge zwykłe w Wiltshire;[24] Wilburgewel w Kent;[24] 25] Willa-byg w Lincolnshire;[26] Wilmanford,[27] Wilmanleáhtun,[28] wydaje się, że pochodzi od imion związanych z tymi ludźmi. Nie udało mi się odkryć, że jakiekolwiek inne plemię kontynentalne z okresu anglosaskiego nosiło taką nazwę, z wyjątkiem tego plemienia Wendów, zwanego przez króla Alfreda ludźmi z Haweli, imię, którego najwyraźniej przetrwało w nazwie Domesday Hauelingas w Essex. Wilte lub Willa, nazwa plemienna, przetrwała w Anglii jako nazwisko, podobnie jak imię narodowe Scot, i znajduje się w XIII-wiecznych Hundred Rolls i innych wczesnych zapisach. W tych zwojach wymienia się dużą liczbę tak nazwanych osób — Wiltes występuje w siedemnastu wpisach, Wilt w ośmiu, a Wilte w czterech wpisach. Wymienia się również Willeman jako imię osobiste.[29] Dobrze znane jest stare, skandogotyckie imię osobiste Wilia.[30]

The great Wendish tribe which occupied the country next to that of the Danes along the west coast of the Baltic in the ninth century was the Obodriti, known also as the Bodritzer. From their proximity there arose an early connection between them and the Danes, or Northmen. In the middle of the ninth century we read of a place on the boundaries of the Northmen and Obodrites, ‘in confinibus Nordmannorum et Obodritorum.’[31] The probability of Wendish people of this tribe having settled in England among the Danes arises from their near proximity on the Baltic, their political connection in the time of Sweyn and Cnut, historical references to Obodrites in the service of Cnut in England, and the similarity of certain place-names in some parts of England colonized by Danes to others on the Continent of known Wendish or Slavonic origin. Obodriti is a Slavic name, and, according to Schafarik, the Slavic ethnologist, the name may be compared with Bodrica in the government of Witepsk, Bodrok, and the provincial name Bodrog in Southern Hungary, and others of a similar kind. In the Danish settled districts of England we find the Anglo-Saxon names Bodeskesham, Cambridgeshire; Bodesham, now Bosham, Sussex; Boddingc-weg, Dorset;[32] the Domesday names Bodebi, Lincolnshire; Bodetone and Bodele, Yorkshire; Bodehā, Herefordshire; Bodeslege, Somerset; Bodeshā, Kent; and others,[33] which may have been named after people of this tribe.

Wielkie plemię Wendów, które w IX wieku zajmowało kraj obok Duńczyków wzdłuż zachodniego wybrzeża Bałtyku, to Obodriti, znani również jako Bodritzer. Z ich bliskości powstał wczesny związek między nimi a Duńczykami lub ludźmi północy. W połowie IX wieku czytamy o miejscu na pograniczu Ludzi Północy i Obodrytów „in confinibus Nordmannorum et Obodritorum”[31]. bliskie sąsiedztwo nad Bałtykiem, ich powiązania polityczne w czasach Sweyna i Knuta, historyczne odniesienia do Obodrytów w służbie Knuta w Anglii oraz podobieństwo niektórych nazw miejscowości w niektórych częściach Anglii skolonizowanej przez Duńczyków do innych na kontynencie znanego pochodzenia wendyjskiego lub słowiańskiego. Obodriti to słowiańskie miano i według Szafarzika, słowiańskiego etnologa, można je porównać do Bodrica w rządzie Witebska, Bodrok, prowincjonalnego Bodrog na południowych Węgrzech i innych podobnych. W osiedlonych duńskich okręgach Anglii znajdujemy anglosaskie nazwy Bodeskesham, Cambridgeshire; Bodesham, obecnie Bosham, Sussex; Boddingc-weg, Dorset; [32] Domesday nazywa Bodebi, Lincolnshire; Bodetone i Bodele, Yorkshire; Bodeha, Herefordshire; Bodeslege, Somerset; Bodesza, Kent; i inne [33], które mogły być nazwane na cześć ludzi z tego plemienia.

The map of Europe at the present day exhibits evidence of the ancient migration of the Slavs. The Slavs in the country from Trient to Venice were known as Wendi, and hence the name Venice or the Wendian territory.[34] Bohemia and Poland after the seventh century became organized States of Slavs on the upper parts of the Elbe and the Vistula. The Slavonic tribes on the frontier or march-land of Moravia formed the kingdom of Moravia in the ninth century. Other scattered tribes of Slavs formed the kingdom of Bulgaria about the end of the seventh century; and westward of these, other tribes organized themselves into the kingdoms of Croatia, Dalmatia, and Servia.[35] In the North the ancient Slav tribes of Pomerania, Mecklenburg, Brandenburg, and those located on the banks of the Elbe, comprising the Polabians, the Obodrites, the Wiltzi, those known at one time as Rugini, the Lutitzes, and the Northern Sorabians or Serbs, became gradually absorbed among the Germans, who formed new States eastward of their ancient limits. These have long since become Teutonised, and their language has disappeared, but the Slavonic place-names still remain.

Mapa Europy na dzień dzisiejszy zawiera dowody na starożytną wędrówkę Słowian. Słowianie w kraju od Triestu do Wenecji byli znani jako Wendi, stąd nazwa Wenecja lub terytorium Wenedian.[34] Czechy i Polska po VII wieku stały się zorganizowanymi Państwami Słowian w górnych partiach Łaby i Wisły. Plemiona słowiańskie na pograniczu Moraw utworzyły królestwo Moraw w IX wieku. Inne rozproszone plemiona Słowian utworzyły królestwo Bułgarii około końca VII wieku; a na zachód od nich inne plemiona zorganizowały się w królestwa Chorwacji, Dalmacji i Serbii.[35] Na północy starożytne plemiona słowiańskie z Pomorza, Meklemburgii, Brandenburgii i tych położonych nad brzegami Łaby, składające się z Połabów, Obodrytów, Wiltzich, znanych niegdyś jako Rugini, Lutitzowie i Sorabowie Północni lub Serbowie zostali stopniowo wchłonięci przez Niemców, którzy utworzyli nowe państwa na wschód od ich starożytnych granic. Te już dawno zostały steutonizowane, ich język zniknął, ale słowiańskie nazwy miejscowe wciąż pozostają.

What concerns us specially in connection with the settlement of England and the Vandals is that these people were Slavs, not Teutons or Germans, as is sometimes stated. They are fully recognised as Slavs by the historian of the Gothic race, who tells us that Slavs differ from Vandals in name only.[36] It is important, also, to note that the Rugians mentioned by Bede were a Wendish tribe. Westward of the Elbe the Slavic Sorabians had certainly pushed their way, before they were finally checked by Charlemagne and his successors. The German annals of the date A.D. 782[37] tell us that the Sorabians at that time were seated between the Elbe and the Saale, where place-names of Slavonic origin remain to this day.

To, co nas szczególnie martwi w związku z osadnictwem Anglów i Wandalów, to fakt, że ci ludzie byli Słowianami, a nie Teutonami czy Niemcami, jak to się czasem mówi. Są oni w pełni uznawani za Słowian przez historyka rasy gockiej, który mówi nam, że Słowianie różnią się od Wandalów tylko nazwą.[36] Należy również zauważyć, że Rugianie wymienieni przez Bede byli plemieniem Wendyjskim. Na zachód od Łaby słowiańscy Sorabianie z pewnością przepychali się, zanim ostatecznie zostali powstrzymani przez Karola Wielkiego i jego następców. Niemieckie annały z roku 782[37] mówią nam, że Sorabowie w tym czasie siedzieli między Łabą a Soławą, gdzie do dziś zachowały się nazwy miejscowości pochodzenia słowiańskiego.

Those Wends who were located on the Lower Elbe, near Lüneburg and Hamburg, were known as Polabians, through having been seated on or near this river, from po, meaning ‘on,’ and laba, the Slavic name for the Elbe.

Ci Wendowie, którzy znajdowali się nad Dolną Łabą, w pobliżu Lüneburga i Hamburga, byli znani jako Połabianie, ponieważ siedzieli na tej rzece lub w jej pobliżu, od słowa „po”, co oznacza „na” i Laba, słowiańska nazwa Łaby.

The eastern comer of the former kingdom of Hanover, and especially that in the circuit of Lüchow, which even to the present day is called Wendland, was a district west of the Elbe, where the Wends formed a colony, and where the Polabian variety of the Wendish language survived the longest. It did not disappear until about 1700-1725, during the latter part of which period the ruler of this ancient Wendland was also King of England.

Wschodni kraniec dawnego królestwa Hanoweru, a zwłaszcza ten w obwodzie Lüchowa, który do dziś nosi nazwę Wendland, był okręgiem na zachód od Łaby, gdzie Wendowie tworzyli kolonię i gdzie najdłużej przetrwał język wendyjski w swojej połabskiej odmianie. Nie zniknął aż do około 1700-1725, w drugiej połowie tego okresu władcą tego starożytnego Wendlandu był także król Anglii.