Chaim Zelig Słonimski (1810 – 1904) i jego maszyna licząca

Z polskiej Wikipedii dowiecie się o nich obydwu trochę, ale o Chaimie Zeligu Słonimskim nie tego co najistotniejsze. Na świecie jest on bowiem uważany za jednego z ważniejszych prekursorów komputera, w wersji mechanicznej maszyny liczącej, o czym jakoś się „Polacy z Wiki” nie rozpisują. Nieco więcej piszą o Szternie.

Chaim Zelig Słonimski (hebr. חיים זליג סלונימסקי, ur. 10 marca 1810 w Białymstoku, zm. 15 maja 1904 w Warszawie) – polski pisarz, matematyk, astronom i wynalazca żydowskiego pochodzenia.

Syn Jakuba Słonimskiego, urodził się w Białymstoku w ortodoksyjnej rodzinie żydowskiej, która zapewniła mu tradycyjne wykształcenie. W 1828 ożenił się z bogatą panną z Zabłudowa i przeniósł się do domu teściów, gdzie samodzielnie studiował matematykę, astronomię i język hebrajski. Rozwiódł się w 1831 i powrócił do Białegostoku.

W 1834 dzięki pomocy sponsora z Wilna, Mojżesza Rozentala wydał w języku hebrajskim podręcznik matematyki Podstawy wiedzy (hebr. Jesodej chochma). W 1835 wydał pierwszą pracę z astronomii zatytułowaną Kometa (aram. Kochawa de-szawit), w której m.in. opisał kometę Halleya. Praca przyniosła mu duży sukces, który zmobilizował go w 1838 do wyjazdu do Warszawy. Tam nawiązał kontakt z polskimi astronomami: Janem Baranowskim i Franciszkiem Armińskim, którzy napisali wstęp do książki Dzieje nieba (hebr. Taldot ha-szamajim), wydanej w 1838 dzięki protekcji matematyka, Abrahama Jakuba Sterna. W 1842 poślubił Sarę, najmłodszą córkę Abrahama Sterna i osiadł w Warszawie na stałe.

W stolicy zajął się udoskonalaniem wynalezionej przez teścia maszyny liczącej, którą przedstawił na wystawach w Królewcu w 1844 i następnie w Sankt Petersburgu w 1845, na której otrzymał nagrodę Cesarskiej Akademii Nauk, a car Mikołaj I Romanow nagrodził go prawem zamieszkania poza rewirem żydowskim w Warszawie. Wynalazek prezentował później w Berlinie, gdzie dzięki Aleksandrowi von Humboldtowi został nagrodzony przez króla Fryderyka Wilhelma IV.

W latach 1846-1858 mieszkał i pracował w Tomaszowie Mazowieckim (według Abrahama Cygielmana). Za nagrodę, którą uzyskał w Londynie za swoją maszynę, Słonimski wydzierżawił ziemię w pobliżu Tomaszowa (według Janiny Kumanieckiej). Prowadził tam eksperymenty z zakresu technologii garncarstwa, metalurgii, hydrostatyki i elektryczności.

W 1850 otrzymał patent na cynowanie naczyń kuchennych z lanego żelaza, a w 1854 na sikawkę strażacką. W 1852 opracował sposób liczenia wstecz lat przestępnych w kalendarzu żydowskim. W 1859 ulepszył działanie telegrafu, dzięki urządzeniu do jednoczesnego przekazywania czterech depesz przez jeden przewód. W 1862 założył popularnonaukowe pismo w języku hebrajskim dla umiarkowanie zasymilowanych i oświeconych Żydów Ha-Cefira (z hebr. Jutrzenka), w którym oprócz propagowania asymilacji pisał o najnowszych osiągnięciach techniki.

W 1861 został inspektorem Szkoły Rabinów w Żytomierzu i jednocześnie cenzorem druków hebrajskich, poprzez co został zmuszony do zawieszenia wydawania Ha-Cefiry, której wydał łącznie 25 numerów. W szkole wraz z żoną Sarą prowadził również kółko dramatyczne. W 1873 szkoła została zamknięta przez władze carskie, wskutek czego Słonimski powrócił do Warszawy.

W 1875 wznowił wydawanie Ha-Cefiry w Berlinie, a następnie w Warszawie. Prowadził je do 1886. Od 1864 działał w Warszawskim Towarzystwie Krzewienia Oświaty wśród Izraelitów. W 1865 opublikował podręcznik do matematyki Podstawy nauki liczenia (hebr. Jesodej chochma ha-sziur).

Zmarł w Warszawie. Został pochowany w alei głównej cmentarza żydowskiego przy ulicy Okopowej w Warszawie (kwatera 71, rząd 1)[1]. Miał czterech synów – przedwcześnie zmarłego w Tomaszowie Mazowieckim Abrama Jakuba (1845-1849), Józefa (1860-1934), Lajba vel Leonida (Ludwika) (1850-1918) i Stanisława (1853-1916). Dwaj ostatni porzucili judaizm – Stanisław dla katolicyzmu, a Leonid dla prawosławia. Jego wnukami byli: Antoni (1895-1976) i Piotr Słonimscy (1893-1944).

Prace

- Mosedej chochma. Podstawy nauki, Wilno 1834

- Kochva de-šavit. Kometa, Wilno 1835

- Toldot ha-šamajim. Dzieje nieba. Warszawa 1838

- Opisanie novago ċislitel’nago instrumenta (Описание нового числительного инструмента). Petersburg, 1845

- Eine allgemeine Formel für die gesamte jüdische Kalender-Berechnung. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 28 (1844)

- Allgemeine Bemerkungen über Rechenmaschinen und Prospectus eines neu erfunden Rechen-Instruments. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (1844)

- Mecijuł ha-nefeš ve Kijuma chuc la-guf. Warszawa, 1852

- Jesode ha-ibur. Warszawa, 1852

- Ot zikaron. Warszawa, 1858

- Jesodej chochmat ha-šiur (1865)

Zobacz też

- Izrael Abraham Staffel

- Abraham Stern

- Charles Xavier Thomas

Przypisy

- Cmentarze m. st. Warszawy. Cmentarze żydowskie. Warszawa: Rokart, 2003. ISBN 83-916419-3-7.

Bibliografia

- A. Cygielman, Tomaszow Mazowiecki, w: Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 15, Jerusalem 1982, s. 1215 (“The mathematician Hayyim Selig Slonimski lived there between 1846 and 1858”);

- Janina Kumaniecka, Saga rodu Słonimskich, Warszawa, Iskry, 2003, ISBN 83-207-1733-7, s. 48-58 (portr. na s. 53);

- Alina Cała, Hanna Węgrzynek, Gabriela Zalewska: Historia i kultura Żydów polskich. Słownik. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2000. ISBN 83-02-07813-1.

- Henryk Kroszczor: Cmentarz Żydowski w Warszawie. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1983, s. 23. ISBN 83-01-04304-0.

- Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak, Słownik biograficzny Żydów tomaszowskich, Łódź – Tomaszów Mazowiecki 2010: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, s. 217-219 (biogram, fot., bibl.), ISBN 978-83-7525-358-0.

Weźmy więc anglojęzyczną stronę poświeconą Historii Komputerów:

History Computer

http://history-computer.com/MechanicalCalculators/19thCentury/Slonimski.html

The Polish/Russian Jew Chaim Zelig Slonimski (see biography of Chaim Zelig Slonimski) was a Hebrew publisher, astronomer, inventor, and science author, a prominent figure in this humble website, due to his inventive calculating machines.

Slonimski was born on 31 March, 1810, in Byelostok, in the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire. His family provided him with a traditional education, and he studied mathematics, astronomy and Hebrew by himself.

Slonimski’s studies in the area of calculating devices commenced probably in 1838, when he, visiting Byelostok, heard that a Jew had spent there several days, to collect subscriptions for tables of calculations, which he had invented. The tables had no success, but Chaim decided to try to produce something better, and having once taken the idea into his head, it was soon accomplished. He return home, and designed a machine to perform addition and subtraction, but he had not the means to complete his instrument.

In late 1830s Chaim Zelig Slonimski settled permanently in Warsaw as guest in the home of Abraham Jakub Stern, the popular mathematician and inventor of various machines (including calculating). This occurred for the young author and scholar who had recently been divorced, thanks to Stern, who wanted him as a son-in-law for his youngest daughter, Sara Gitel. The match was finalized at the beginning of 1842, one month before Stern’s death. There is no doubt, that Slonimski was heavily influenced by his mentor and father-in-law Stern, but besides this valuable legacy, Slonimski must have been a very smart man, judging by the rest of his life.

Three calculating machines were invented and produced by Slonimski before 1843, one for addition and subtraction, one logarithmic device, and one for multiplication. The first account of his calculating devices is from September 1839, when he wrote to a friend, that he had built a calculating machine and that he was working on a 20-digit logarithmic device.

It seems Slonimski demonstrated firstly the adding machine, because in the June 1840 issue of the Vilnius newspaper Kuryer Litewski was announced (at that time Slonimski was in Vilnius to publish his mathematical handbook):

A Jew Slonimski born in Bialystok, recently invented a small machine for calculating, which thanks to its dimensions (length 10 inches, width 3 inches and 1 inch height), comfort, and low price deserves to be widely used. Everybody who knows digits only can, with the help of this machine, make calculations easily, fast, and without need to think. This machine can be seen at the inventor’s residence, where he is now working on a new machine for calculating logarithms. With the help of this machine one can simply and comfortably find the differences of Bruget logarithms,as well as natural logarithms up to 14 decimal digits.

The adding machine was presented also in 1841 in Königsberg, where Slonimski was invited through the recommendation of Bessel, the great astronomer, who taught at the university. Slonimski got permission to expose for inspection, in the university building, his calculating machine and had the pleasure to see it highly approved by the whole faculty. Slonimski obviously described (or demonstrated) his logarithmic device also, because there is a letter from Carl Gustav Jacobi to his brother, asking for support for Slonimski to demonstrate it in St. Petersburg.

The multiplication machine was based on a newly discovered theorem from number theory, called the Slonimski Theorem. The operation of the multiplication machine, which is more important, has been described by Slonimski himself in Russian. In principle, it was an implementation of multiplication tables, which resulted from application of the Theorem. Since the amount of related numbers was not that large, they were put on the cylinders, which—when moved appropriately—were showing the multiplication results in small windows.

Slonimski’s machines got high recognition during his life time. In August, 1844, he brought his machines to Berlin, where he demonstrated them first to some prominent scientist as Alexander von Humboldt, Friedrich Bessel, Johann Encke, and others, then to the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences, and his work was highly appreciated. The accurate results of his machines gained him here the same approbation, and although he did not communicate the theoretical principles on which the whole rests, yet, Humboldt recommended him to the Friedrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia, where he saw, at his representation, his machines highly approved. Humboldt even intended to provide him with material means so that he could settle in Berlin and then occupy the chair of mathematics in one of the Prussian universities, but family circumstances prevented Slonimski from taking advantage of this offer.

In the same 1844, Slonimski published an article on calculating machines in the Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, vol. 26, 1844, pp. 184–190 (see the article of Slonimski). In 1845 an article „Selig Slonimski and His Calculating Instrument” was published Illustrierte Zeitung, Leipzig, vol. 5, no. 110, 1845, pp. 90–92 (see the article for Slonimski).

Next year, in April of 1845, he presented the multiplication machine to the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, and obtained its recommendation for the Demidov Prize of the Second Grade (The Second Grade prize amounted to 2500 Rubles. For comparison, one should say that a university scholarship of 20 Roubles per 1 month could easily cover a student’s living and educational expenditures.), which was awarded to him on 24 June, 1845. Moreover, the President of the Academy, Minister von Uwaroff, presented the inventor before the Emperor, and a few days afterwards the following Ukase appeared:

“Ukase to the Senate.

“The Hebrew, Selig Slonimski, born in the city of Bialystok, is hereby, in approval of the high merits which his learned and useful labours in the Mathematical branch have gained, raised to the rank of an Honorary Citizen.

“Nicolas I.

“Peterhof, 26th July, 1845.”

In 1847 Slonimski applied for a patent in USA (see the petition of Slonimski), stating that there was a company in New York— Neustadt and Barnett (of two Jews from Warsaw named Samuel J. Neustadt and David Barnett), who were interested in financing his invention and they apparently paid $300—at that time a very large sum of money—in order to get a patent. For unknown reason, this application was unsuccessful. Barnett managed however to obtain a Great Britain patent on Slonimski’s behalf for the adding device and the third model of his multiplying device (British patent number 11441 of 1847). By a stroke of luck Slonimski managed to sell the rights of the manufacture of his adding machine to England for £400. He invested the money in the acquisition of a fruit orchard in the town of Tomashov.

więcej: http://history-computer.com/MechanicalCalculators/19thCentury/Slonimski.html

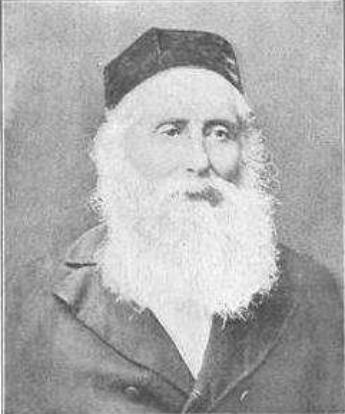

Abraham Jakub Stern (1762 – 1842) – prekursor cybernetyki

Abraham Jakub Stern, inna pisownia Sztern (ur. pomiędzy 1762 a 1769 w Hrubieszowie, zm. 3 lutego 1842 w Warszawie) – polski Żyd, zegarmistrz, mechanik (samouk), konstruktor, uczony, wynalazca, uznawany za jednego z prekursorów cybernetyki[1]. Wynalazca kilku maszyn liczących, dalmierza geodezyjnego, tartaku mechanicznego, młockarni oraz żniwiarki konnej[1].

Był przodkiem Antoniego Słonimskiego i Nicolasa Slonimsky’ego, którzy byli jego prawnukami. Jego najmłodsza córka, Sara, wyszła w roku 1842 za Chaima Zeliga Słonimskiego, dziadka Antoniego Słonimskiego. Jego syn Izaak Stern był nauczycielem w Warszawskiej Szkole Rabinów.

Wynalazki

Od 1810 Abraham Stern skonstruował serię maszyn liczących, które wykonywały cztery podstawowe działania arytmetyczne i potrafiły również wyciągać pierwiastki kwadratowe. Jako chłopiec terminował u zegarmistrza w Hrubieszowie. Tam zainteresował się nim Stanisław Staszic, który umożliwił mu przeprowadzkę do Warszawy oraz podjęcie tam studiów[1]. Stern wykazywał niepospolite zdolności matematyczne i wynalazcze. Sporządził tak zwany trianguł ruchomy o dwóch celownikach, zastępujący stolik mierniczy.

Znany był też prosty mechanizm Sterna, zabezpieczający powozy przed rozbieganiem się koni. Najwięcej czasu i wysiłku poświęcił skonstruowaniu „machiny rachunkowej”, aby w końcu zaprezentować gotowe dzieło Staszicowi i dowieść, że nie zawiódł pokładanych w nim nadziei. Zademonstrowana na posiedzeniu Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauk „machina” wywołała sensację, wykonywała bowiem „sama przez się” wszystkie cztery działania.

Po czterech kolejnych latach pracy Stern zbudował nową maszynę służącą wyłącznie do wyciągania pierwiastków kwadratowych. Wreszcie 30 kwietnia 1817 zaprezentował maszynę stanowiącą niejako skojarzenie dwóch poprzednich, wykonywała bowiem wszystkie pięć działań. W jednym z modeli wystarczyło wprowadzić dane i operacja była wykonywana przez mechanizm zegarowy, bez ingerencji człowieka. Od 1830 członek Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauk.

Członek Komisji Żydowskiej przy Warszawskiej Szkole Rabinów oraz jej rektor w latach 1826–1835.

Został pochowany na cmentarzu żydowskim na Bródnie w Warszawie[2].

Zobacz też

Przypisy

- Iłowiecki 1981 ↓, s. 150.

- Jerzy S. Majewski, Tomasz Urzykowski: Spacerownik po warszawskich cmentarzach. Warszawa: Agora, 2009, s. 140. ISBN 978-83-7552-713-1.

Literatura

- Maciej Iłowiecki: Dzieje nauki polskiej. Warszawa: Interpress, 1981. ISBN 83-223-1876-6.

- 2.2.4 Kalkulatory mechaniczne. W: Piotr Gawrysiak: Cyfrowa rewolucja. Rozwój cywilizacji informacyjnej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2008, s. 72. ISBN 978-83-01-15607-7.

- Halina Winnicka: Zapomniany wynalazca, Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych, Warszawa 1962

Linki zewnętrzne

- Prace Abrahama Sterna i o nim dostępne w Sieci (Katalog HINT)

- Abraham Stern

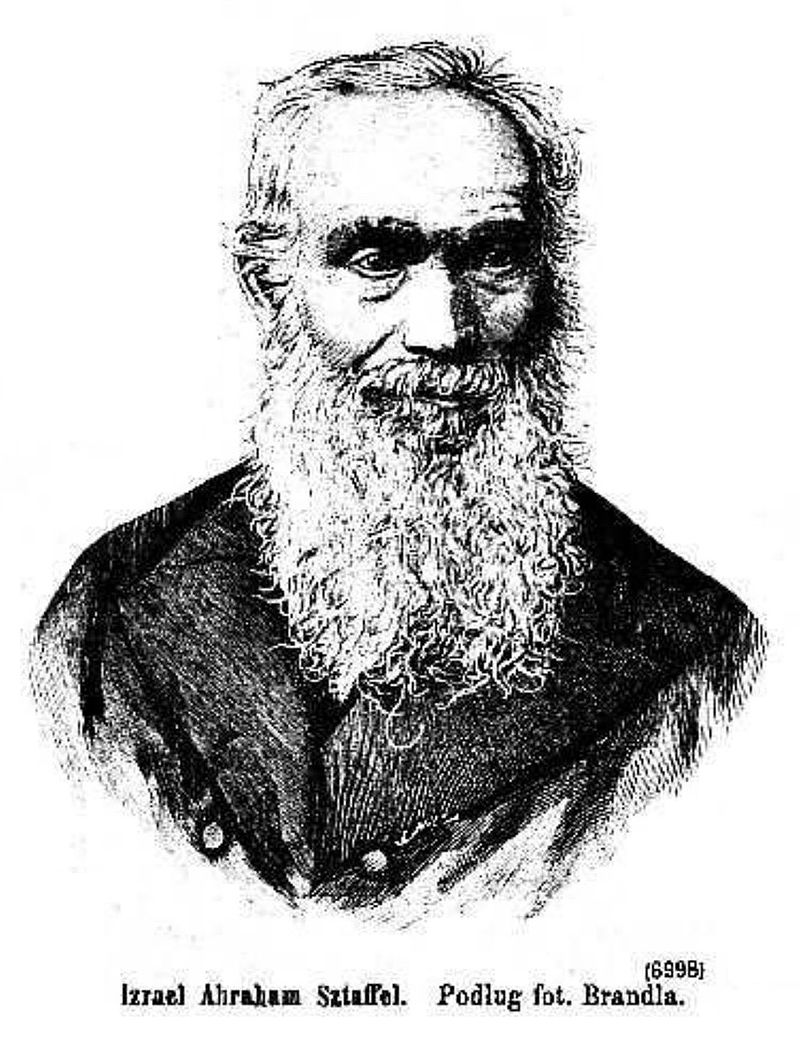

Izrael Abraham Staffel (1814 – 1884)

Izrael Abraham Staffel (ur. 1814, zm. 1884 w Warszawie) – polski wynalazca pochodzenia żydowskiego, warszawski zegarmistrz, mechanik, twórca m.in. maszynki rachunkowej – arytmometru. Wynalazca wielu precyzyjnych mechanizmów, z których anemometr i probież aliaży (przyrząd do badania składu stopów metali szlachetnych w oparciu o prawo Archimedesa), znajdują się w zbiorach muzeum Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

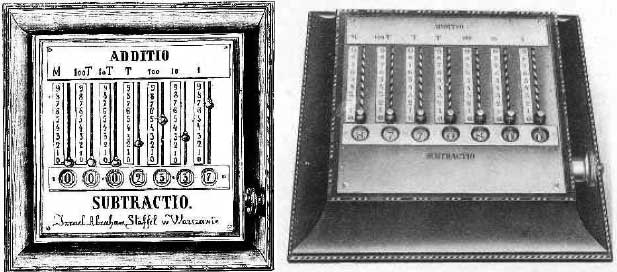

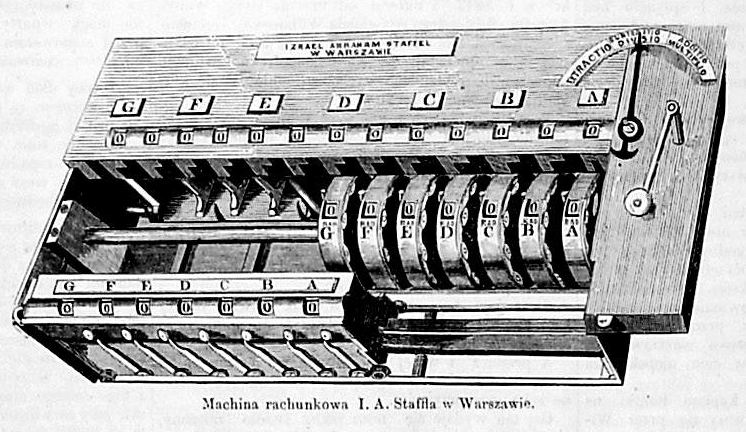

Maszyna licząca Staffela

Najbardziej znany jego wynalazek to maszynka rachunkowa, która wykonywała funkcje dodawania, odejmowania, mnożenia, dzielenia, podnoszenia do potęg i wyciągania pierwiastków kwadratowych. Był to typ maszyny walcowej złożonej z siedmiu zestawów walców wzajemnie sprzężonych.

Wykonana po 10 latach prac, została zaprezentowana na wystawie przemysłowej w Warszawie w 1845, następnie w Akademii Nauk w Petersburgu, gdzie uzyskała równie wysokie oceny jak w Warszawie. W 1851 pokazana na pierwszej wystawie międzynarodowej w Londynie, gdzie otrzymuje medal.

Inne wynalazki

Innym znanym wynalazkiem była liczebnica mechaniczna realizująca tylko dwa działania matematyczne – dodawanie i odejmowanie. Wykonana w postaci siedmiu walców z liczbami pozwalała na wykonywanie działań na liczbach od 0 do 9 000 000. W założeniu urządzenie miało wyprzeć popularne szczoty (czyli liczydła), lecz na skutek ceny, jak i czasu obsługi nie przyniosły wynalazcy dochodu.

Powstały nie więcej jak dwa modele jego maszyn, a jedyny zachowany egzemplarz znajduje się w Muzeum Techniki w Warszawie.

Linki zewnętrzne

- Tygodnik Ilustrowany 1863, Machina Rachunkowa p. Izraela Abrahama Staffel z Warszawy

Tyle po polsku a teraz po angielsku:

Izrael Abraham Staffel – History Computer

http://history-computer.com/MechanicalCalculators/19thCentury/Staffel.html

The Polish Jew Izrael Abraham Staffel was born in 1814 to an impoverished family in Warsaw, Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. His primary education he got at an elementary religious Jewish school, and later entered as an apprentice in a watchmaking factory. There he learned the Polish language, which enabled him to read scientific and technical books and deepen his expertise.

In 1833, when he was only 19, Staffel opened a clockmaker shop in Warsaw (at Marszałkowska str. 125), then he opened another workshop at Grzybowskiej and Gnojnej str., where he worked till the end of his life. Staffel spent most of his life on developing various inventions, primarily the calculating machines, for which he obtained multiple prizes, but he also invented other devices, such as an anemometer, Ventilator Helis (a powerfull fan), a probe for determining the contents of alloys, a counterfitting machine, and a two-colour printing press, used for printing stamps and banknotes (on this machine that printed the first Polish post stamp, the so-called Poland No. 1, in the Stempel Factory in Warsaw). Unfortunately, he did not manage to patent any of his inventions and died extremely poor after long illness in 1885 in Warsaw.

The distinguished Jewish historian Jacob Shatzky (1893-1956) asserts that Staffel was a relative of Abraham Jakub Stern. If this is true, probably Staffel was inspired by Stern and received from him valuable information about construction of the calculating machines. Anyway, it is hard to believe that the young watchmaker Staffel didn’t know Abraham Stern, who was one of the most remarkable figures in the Warsaw Jewish community during the first decades of 19th century, and who also used to work as a watchmaker in his youth.

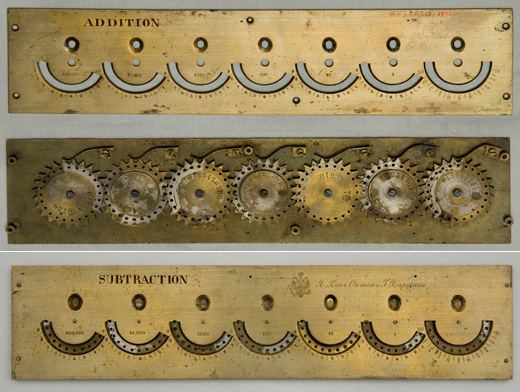

Staffel commenced his ocasions with calculating machines around 1835, but his first machine, based on pin-wheels of Poleni, was ready in 1842 and was demonstrated at the industrial exhibit in Warsaw as late as in 1845 (by recommendation from the Minister Sergey Uvarov (Серге́й Семёнович Ува́ров), and it received a silver medal (now this machine is preserved in the Museum of Technology in Warsaw, see the lower photo). This machine can be used for addition and subtraction only.

Staffel’s machine (property of Muzeum Techniki in Warsaw, Poland)

In 1846, Staffel’s machine was demonstrated and was very positively assessed by the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. Two famous mathematicians, V. Bunyakovsky (later creator of a calculating device also, see Самосчеты Буняковского) and B. Jacobi, gave it a very positive opinion and Staffel was awarded a very prestigious Demidov prize. Later on the machine was presented to the Russian Emperor Nikolai I, who was so astonished with this invention, that he ordered a sum of 1500 silver roubles to be paid to the inventor.

Later on Staffel improved his first machine, placing the calculating mechanism on a movable rail, and manufactured a calculating machine for adding, subtracting, multiplication and division (plus square-root). In 1851, the second machine was exposed to the Great Exposition in Crystal Palace in London, where it was awarded with a gold medal. The report, describing the calculating machines presented at the Exhibit, says the following about Staffel’s machine: “The best machine of this kind exhibited is that of Staffel (Russia, 148), which, on examination, seems to combine accuracy with economy of time, and works easily and directly”.

The machine was evaluated higher than the machine of Thomas de Colmar, which was a real sensation. The newspaper Illustrated London News also published an enthusiastic article, with the description of the machine and its picture: “In the Russian Court, modestly secluded amidst the glitter of malachite doors and vases, jewelry and silver, there is one work, the produce of high intelligence, and intended to assist in certain intellectual labors. This solitary tribute of mind to minds comes not from Petersburg, nor Mexico [meant Moscow], nor from Siberia, nor from the Ural Mountains, but from Poland. We refer to Staffel’s Calculating Machine, №148 in the Catalogue”.

Drawing of the Staffel’s machine in the Illustrated London News

Let’s mention also the description of the machine in the newspaper Illustrated London News:

The machine is of the size of an ordinary toilet: the mechanism is 18 inches by 9, and about 4 inches high. The external mechanism represents three rows of ciphers. The first and upper row, containing 13 ciphers, is immovable; the second and third, containing 7 ciphers, are movable. To the right is a semicircular ring, containing the words Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication, Division and Extraction. Underneath is a hand, which serves as a regulator for the operation, pointing ad libitum to either of the four rules or the square root, whichever is to be worked. The advantage which this machine has above others are as follows:

1. That the four rules and the square root, with fractions, can be worked by means of a curved handle (which in itself is a piece of mechanism), showing the various sums alternatively, without being obliged to note down any auxiliary figure, as is the case with all other calculating machines.

2. That all compound rules, as the rule of three, of five, etc., can be worked by transposition of the regulator, without shifting any of the figures.

3. That, if by subtraction a larger number is subtracted from a smaller, the sound of a bell is heard, indicating the false proceeding; and when turning the handle a negative number shows itself in the upper row, where, instead of the 13 ciphers, the figure 9 will appear in their place, and which, added to the number given, will prove the inverted position of the number. The bell will also be heard if, by division, the handle is turned once too many. A retractive move of the handle will then retrieve the error.

4. That the entire mechanism is of a simple construction, the parts acting without springs, its correctness and accuracy secured, and the efficiency of the mechanism guaranteed.

Even many years later, in the Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal Exposition, 1867, Staffel’s machine is praised in Chapter XVIII “Metrology and Mechanical Calculation”: Of the numerous calculating machines which have been proposed or constructed since that of Mr. Thomas became an ascertained success, those of Messrs. Maurel & Jayet of France, and of Mr. Staffel of Russia, are the only ones which, so far as is known, have solved the problem in a manner entirely satisfactory.

Staffel invented also another, a simpler calculating machine, used for adding and subtraction (see the picture below), similar to the machine of Kummer. This machine is now preserved in Braunsweig Landesmuseum, Germany.