Wielcy Polacy: Leonid Hurwicz (1917-2008) – Nobel z ekonomii

Leonid Hurwicz, laureat Nagrody Nobla z ekonomii w 2007 r., urodził się w Moskwie kilka miesięcy przed rewolucją. Jego rodzice byli Polakami. Mieszkali w Warszawie. Do Moskwy trafili podczas I wojny światowej, gdy większość rodziny została ewakuowana z Kongresówki. Wrócili do Warszawy w obawie przed bolszewikami na początku 1919 r. Hurwicz przebywał w kraju dłużej niż Maria Skłodowska. Mieszkał w Warszawie od momentu, gdy skończył półtora roku. W 1938 r. ukończył studia prawnicze na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim. Do Londynu wyjechał tuż przed wkroczeniem Niemców do Polski we wrześniu 1939 r. Potem przedostał się do Szwajcarii i USA. Podobnie jak Józefa Rotblata uchroniło go to przed Holocaustem.

Wikipedia:

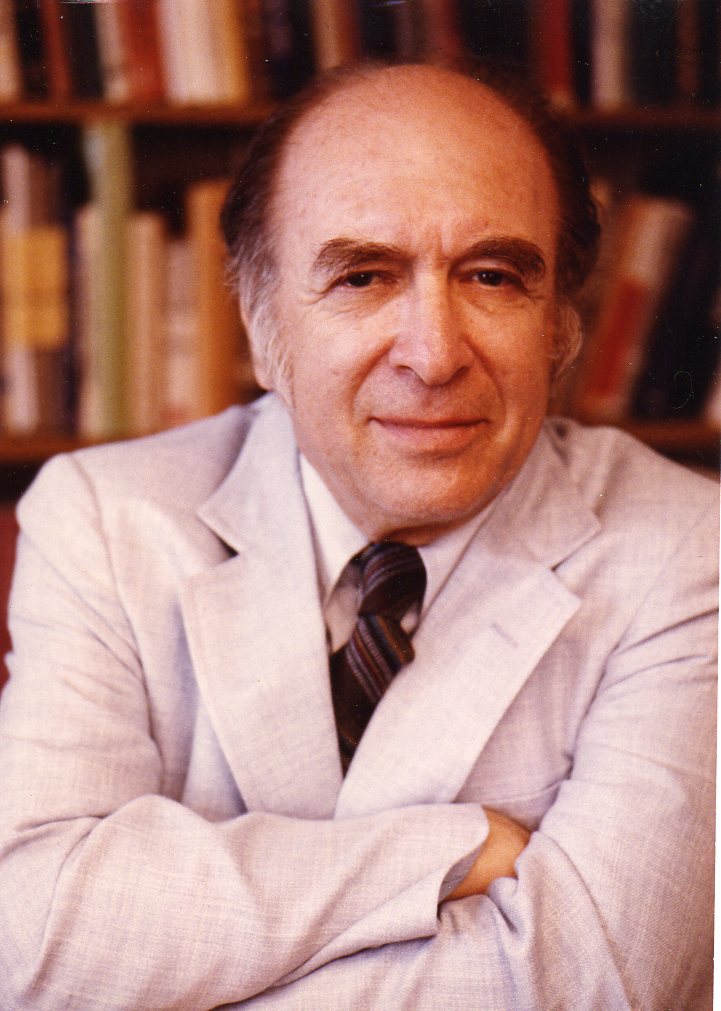

Leonid Hurwicz (ur. 21 sierpnia 1917 w Moskwie, zm. 24 czerwca 2008 w Minneapolis) – polski i amerykański ekonomista żydowskiego pochodzenia, profesor emeritus Uniwersytetu Minnesota, laureat Nagrody im. Alfreda Nobla w dziedzinie ekonomii w 2007.

Pochodził z rodziny polskich Żydów, która ewakuowana z Królestwa Polskiego w czasie I wojny światowej schroniła się na krótko w Moskwie. Na początku 1919 wraz z rodziną powrócił do Warszawy.

W 1938 ukończył prawo na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim. W latach 1938–1939 studiował w London School of Economics, a następnie 1939–1940 w Genewskim Instytucie Wyższych Studiów Międzynarodowych. W 1940 emigrował do USA gdzie kontynuował studia ekonomiczne na Uniwersytecie Chicagowskim i Uniwersytecie Harvarda.

Podczas swojej kariery zawodowej pracował na wielu renomowanych uniwersytetach w USA w Minnesocie, Illinois, Chicago, Harvard, MIT, Berkeley, Stanford. Pracował także w krajach dalekiego wschodu jak – Indonezja, Indie, Chiny, Japonia. Był pracownikiem organizacji międzynarodowych (EKG ONZ – 1948) oraz konsultantem amerykańskich agencji rządowych i instytucji jak np. RAND Corporation.

W działalności naukowej interesował się różnymi dziedzinami ekonomii – teorii równowagi ogólnej (w tym teorii wymiany), teorii popytu, konsumpcji i dobrobytu, teorii cen, teorii rozwoju i planowania. W latach 50. pracował wraz z późniejszym noblistą Kennethem Arrowem nad zagadnieniami programowania nieliniowego. Największe zainteresowanie środowiska ekonomistów przyciągnęły prace Hurwicza w zakresie badań nad decentralizacją (dekompozycją) i efektywnością systemów ekonomicznych oraz procesów alokacji zasobów.

Nagrody i wyróżnienia

Leonid Hurwicz był przewodniczącym Econometric Society oraz członkiem National Academy of Sciences oraz American Academy of Arts and Sciences. W 1980 otrzymał tytuł doktora honoris causa Northwestern University, w 1989 Uniwersytetu Autonomicznego w Barcelonie, w 1993 Uniwersytetu Chicagowskiego i Uniwersytetu Keiō, w 1994 Szkoły Głównej Handlowej[1], a w 2004 Uniwersytetu w Bielefeld.

15 października 2007 otrzymał, wraz z Erikiem S. Maskinem i Rogerem Myersonem Nagrodę Banku Szwecji im. Alfreda Nobla[2] za prace nad teorią wdrażającą systemy matematyczne w procesy gospodarcze, która przy zastosowaniu równań matematycznych i algorytmów pozwala ocenić prawidłowość funkcjonowania rynków. Teoria pomogła określić ekonomistom skuteczne mechanizmy rynkowe, schematy regulacji i procedury wyborów i dziś odgrywa główną rolę w wielu dziedzinach ekonomii oraz w naukach politycznych.

Wraz z żoną Evelyn Hurwicz (z domu Jensen, urodzoną 31 października 1921) mieszkał w południowym Minneapolis, Minnesota w Stanach Zjednoczonych. Miał czworo dzieci: Sarah, Michael, Ruth i Maxim.

Publikacje

- Stochastic Models of Economic Fluctuations, 1944, Econometrica

- The Theory of Economic Behavior, 1945, AER

- Theory of the Firm and of Investment, 1946, Econometrica

- What Has Happened to the Theory of Games?, AER

- Reduction of Constrained Maxima to Saddle-Point Problems with K.J.Arrow, 1956, Proceedings of the Third Berkeley Symposium

- Gradient Methods for Constrained Maxima, with K.J. Arrow, 1957, Operations Research

- Studies in Linear and Non-Linear Programming with K.J.Arrow and Hirofumi Uzawa, 1958

- On the Stability of Competitive Equilibrium I, with K.J. Arrow, 1958, Econometrica

- On the Stability of Competitive Equilibrium, II, with K.J. Arrow, J.D. Block, 1959, Econometrica

- Competitive Stability under Weak Gross Substitutability: the Euclidian distance approach with K.J. Arrow, 1960, IER

- Some Remarks on the Equilibria of Economic Systems with K.J. Arrow, 1960, Econometrica

- Conditions for Economic Efficiency of Centralized and Decentralized Structures, 1960, in Grossman, editor, Value and Plan

- Optimality and Informational Efficiency in Resource Allocation, 1960, in Arrow, Karlin and Suppes, editors, Mathematical Methods in Social Sciences

- Constraint Qualifications in Non-Linear Programming, with K.J. Arrow and H. Uzawa, 1961, Naval Research Logistics Quarterly

- On the Problem of Integrability of Demand Functions, 1971, in Chipman et al, editors, Preferences, Utility and Demand

- On the Integrability of Demand Functions, with H. Uzawa, 1971, in Chipman et al, editors, Preferences, Utility and Demand

- Revealed Preference without Demand Continuity Assumptions, with M.K. Richter, 1971, in Chipman et al, editors, Preferences, Utility and Demand

- Centralization and Decentralization in Economic Processes, 1971, in Eckstein, editor, Computation of Economic Systems

- On Informationally Decentralized Systems, 1971, in McGuire, and Radner, editors, Decision and Organization.

- The Design of Mechanism for Resource Allocation, 1973, AER

- Studies in Resource Allocation Processes, with K.J. Arrow, 1977

- On the Dimensional Requirements of Informationally Decentralized Pareto-Satisfactory Processes, 1977, JET

- Ville Axioms and Consumer Theory, with M.K. Richter, 1978, Econometrica

- Construction of Outcome Functions guaranteeing Existence and Pareto-optimality of Nash Equilibria, with D. Schmeidler, 1979, Econometrica.

- Outcome Functions Yielding Walrasian and Lindahl Allocations at Nash Equilibrium Points, 1979, RES

- On Allocations Attainable through Nash Equilibria, 1979, JET

- Incentive Aspects of Decentralization, 1986, in Arrow and Intriligator, editors, Handbook of Mathematical Econ – Vol. III – intro

- On the Stability of the Tatonnement Approach to Competitive Equilibrium’”, 1986, in Sonnenschein, editor, Models of Economic Dynamics

- On the Implementation of Social Choice Rules in Irrational Societies, 1986, in Heller et al., editors, Essays in Honor of Kenneth J. Arrow, Vol. I

- Discrete allocation mechanisms: Dimensional requirements for resource-allocation mechanisms when desired outcomes are unbounded. with T. Marschak, 1985, J of Complexity

- Approximating a function by choosing a covering of its domain and k points from its range, with T. Marschak, 1988, J of Complexity

- Implementation and Enforcement in Institutional Modeling, 1993, in Barnett et al., editors, Political Economy

- Feasible Nash Implementation of Social Choice Rules When the Designer Does not Know Endowment or Production Sets with E. Maskin and A. Postlewaite, 1995, in Ledyard, editor, Economics of Informational Decentralization

- Doktorzy honoris causa. Szkoła Główna Handlowa w Warszawie.

- Three Share Nobel in Economics for Work on Social Mechanisms. The New York Times, 16 października 2007.

- Hurwicz Nobel Prize lecture

- Perspectives on Leo Hurwicz (conference program and photos) University of Minnesota (econ.umn.edu)

Wiki english – bez porównania więcej i dokładniej!

Leonid „Leo” Hurwicz (August 21, 1917 – June 24, 2008) was a Polish American economist and mathematician.[1][2] He originated incentive compatibility and mechanism design, which show how desired outcomes are achieved in economics, social science and political science. Hurwicz shared the 2007 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (with Eric Maskin and Roger Myerson) for work on mechanism design.[3] Hurwicz is the oldest Nobel Laureate, having received the prize at the age of 90.

Hurwicz was educated and grew up in Poland, and became a refugee in the United States after Hitler invaded Poland in 1939. In 1941, Hurwicz worked as a research assistant for Paul Samuelson at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Oskar Lange at the University of Chicago. He was a research associate for the Cowles Commission between 1942 and 1946. In 1946 he became an associate professor of economics at Iowa State College. Hurwicz joined the University of Minnesota in 1951, becoming Curtis L. Carlson Regents Professor of Economics in 1989. He was Regents’ Professor of Economics (Emeritus) at the University of Minnesota when he died in 2008.

Hurwicz was among the first economists to recognize the value of game theory and was a pioneer in its application.[4][5] Interactions of individuals and institutions, markets and trade are analyzed and understood today using the models Hurwicz developed.[6]

Hurwicz was born in Moscow, Russia, to a family of Polish Jews a few months before the October Revolution. Soon after Leonid’s birth, the family returned to Warsaw.[7] Hurwicz and his family experienced persecution by both the Bolsheviks and Nazis,[8] as he again became a refugee when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. His parents and brother fled Warsaw, only to be arrested and sent to Soviet labor camps. Hurwicz, who had graduated from Warsaw University in 1938, at the time of Nazi invasion on Poland was in London, moved to Switzerland then to Portugal and finally in 1940 he emigrated to the United States. His family eventually joined him there.[9][10]

Hurwicz hired Evelyn Jensen (born October 31, 1923), who grew up on a Wisconsin farm and was, at the time, an undergraduate in economics at the University of Chicago, as his teaching assistant during the 1940s. They married on July 19, 1944[11] and later lived at a number of locations in Minneapolis. They had four children: Sarah, Michael, Ruth and Maxim.[9]

His interests included linguistics, archaeology, biochemistry and music.[7] His activities outside the field of economics included research in meteorology and membership in the NSF Commission on Weather Modification. When Eugene McCarthy ran for president of the United States, Hurwicz served in 1968 as a McCarthy delegate from Minnesota to the Democratic Party Convention and a member of the Democratic Party Platform Committee. He helped design the ‚walking subcaucus‚ method of allocating delegates among competing groups, which is still used today by political parties. He remained an active Democrat, and attended his precinct caucus in February 2008 at the age of 90.[11]

He was hospitalized in mid-June 2008, suffering from renal failure. He died a week later in Minneapolis.[12][13]

Encouraged by his father to study law,[7] in 1938 Hurwicz received his LL.M. degree from the University of Warsaw, where he discovered his future vocation in economics class. He then studied at the London School of Economics with Nicholas Kaldor and Friedrich Hayek.[9] In 1939 he moved to Geneva where he studied at the Graduate Institute of International Studies.[7][14] After moving to the United States he continued his studies at Harvard University and the University of Chicago.[7] Hurwicz had no degree in economics. In 2007 he said, „Whatever economics I learned I learned by listening and learning.”[15]

In 1941 Hurwicz was a research assistant to Paul Samuelson at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and to Oskar Lange at the University of Chicago.[11] At Illinois Institute of Technology during the war, Hurwicz taught electronics to the U.S. Army Signal Corps.[16] From 1942 to 1944, at the University of Chicago, he was a member of the faculty of the Institute of Meteorology and taught statistics in the Department of Economics. About 1942 his advisors were Jacob Marschak and Tjalling Koopmans at the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics at the University of Chicago,[17] now the Cowles Foundation at Yale University.

Hurwicz received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1945–1946.[14] In 1946 he became an associate professor of economics at Iowa State College.[11] From January 1942 until June 1946, he was a research associate for the Cowles Commission. Joining full-time in October 1950 until January 1951, he was a visiting professor, assuming Koopman’s classes in the Department of Economics, and led the commission’s research on theory of resource allocation.[14] He was also a research professor of economics and mathematical statistics at the University of Illinois, a consultant to the RAND Corporation through the University of Chicago and a consultant to the U.S. Bureau of the Budget.[18] Hurwicz continued to be a consultant to the Cowles Commission until about 1961.[19]

Hurwicz was recruited by Walter Heller[8] to the University of Minnesota in 1951, where he became a professor of economics and mathematics in the School of Business Administration.[14] He spent most of the rest of his career there, but it was interspersed with studies and teaching elsewhere in the United States and Asia. In 1955 and again in 1958 Hurwicz was a visiting professor, and a fellow on the second visit, at Stanford University and there in 1959 published „Optimality and Informational Efficiency in Resource Allocation Processes” on mechanism design.[11] He taught at Bangalore University in 1965 and, during the 1980s, at Tokyo University, People’s University (now Renmin University of China) and the University of Indonesia. In the United States he was a visiting professor at Harvard (1969), at the University of California, Berkeley (1976–1977),[20] at Northwestern University twice in 1988 and 1989, at the University of California, Santa Barbara (1998), the California Institute of Technology (1999) and the University of Michigan in (2002). He was a visiting Distinguished Professor at the University of Illinois in 2001.[11]

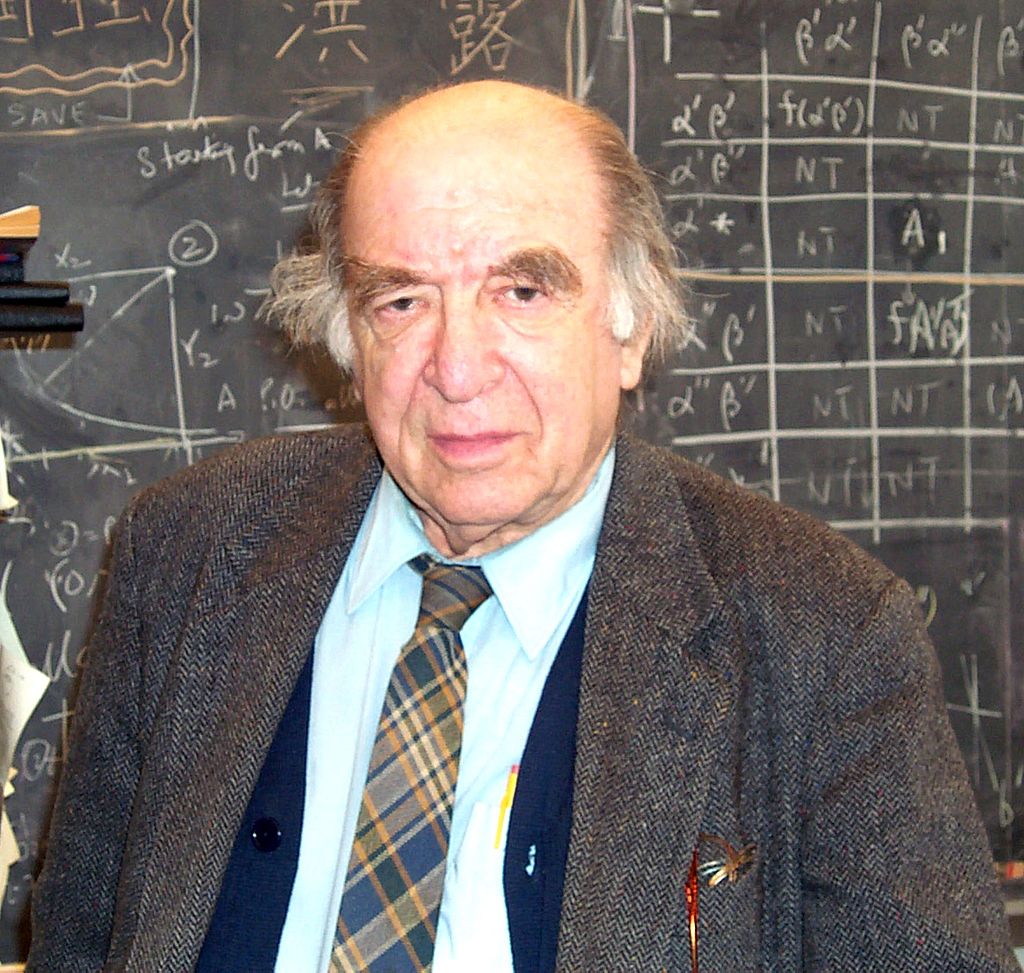

Back at Minnesota, Hurwicz became chairman of the Statistics Department in 1961, Regents Professor of Economics in 1969, and Curtis L. Carlson Regents Professor of Economics in 1989.[11] He taught subjects ranging from theory to welfare economics, public economics, mechanisms and institutions and mathematical economics.[8] Although he retired from full-time teaching in 1988,[10] Hurwicz taught graduate school as professor emeritus most recently in the fall of 2006.[10] In 2007 his ongoing research was described by the University of Minnesota as „comparison and analysis of systems and techniques of economic organization, welfare economics, game-theoretic implementation of social choice goals, and modeling economic institutions.”[21]

Hurwicz’s interests included mathematical economics and modeling and the theory of the firm.[5] His published works in these fields date back to 1944.[22] He is internationally renowned for his pioneering research on economic theory, particularly in the areas of mechanism and institutional design and mathematical economics. In the 1950s, he worked with Kenneth Arrow on non-linear programming;[5] in 1972 Arrow became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Economics prize.[23] Hurwicz was the graduate advisor to Daniel McFadden,[24] who received the prize in 2000.[25]

Earlier economists often avoided analytic modeling of economic institutions. Hurwicz’s work was instrumental in showing how economic models can provide a framework for the analysis of systems, such as capitalism and socialism, and how the incentives in such systems affect members of society.[26] The theory of incentive compatibility that Hurwicz developed changed the way many economists thought about outcomes, explaining why centrally planned economies may fail and how incentives for individuals make a difference in decision making.[24]

Hurwicz served on the editorial board of several journals. He co-edited and contributed to two collections for Cambridge University Press: Studies in Resource Allocation Processes (1978, with Kenneth Arrow) and Social Goals and Social Organization (1987, with David Schmeidler and Hugo Sonnenschein). His most recent articles were published in the journals „Economic Theory” (2003, with Thomas Marschak), „Review of Economic Design” (2001, with Stanley Reiter) and „Advances in Mathematical Economics” (2003, with Marcel K. Richter).[27] Hurwicz presented the Fisher-Schultz (1963), Richard T. Ely (1972), David Kinley (1989) and Colin Clark (1997) lectures.[citation needed]

Awards and honors

Memberships and honorary degrees

Hurwicz was elected a fellow of the Econometric Society in 1947 and in 1969 was the society’s president. Hurwicz was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1965.[28] In 1974 he was inducted into the National Academy of Sciences and in 1977 was named a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association.[9] Hurwicz received the National Medal of Science in 1990 in Behavioral and Social Science, presented to him by President of the United States George H. W. Bush, „for his pioneering work on the theory of modern decentralized allocation mechanisms”.[5][11]

He served on the United Nations Economic Commission in 1948 and the United States National Research Council in 1954. In 1964 he was a member of the National Science Foundation Commission on Weather Modification. He was a member of the American Academy of Independent Scholars (1979) and a Distinguished Scholar of the California Institute of Technology (1984).[11]

Hurwicz received six honorary doctorates, from Northwestern University (1980), the University of Chicago (1993), Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (1989), Keio University (1993), Warsaw School of Economics (1994) and Universität Bielefeld (2004).[9] He was an honorary visiting professor of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology School of Economics (1984).[29]

Named for Hurwicz

First presented in 1950, the Hurwicz criterion is thought about to this day in the area of decision making called „under uncertainty.”[30][31][32] Abraham Wald published decision functions that year.[33] Hurwicz combined Wald’s ideas with work done in 1812 by Pierre-Simon Laplace.[34] Hurwicz’s criterion gives each decision a value which is „a weighted sum of its worst and best possible outcomes” represented as α and known as an index of pessimism or optimism.[31] Variations have been proposed ever since and some corrections came very soon from Leonard Jimmie Savage in 1954.[30] These four approaches– Laplace, Wald, Hurwicz and Savage– have been studied, corrected and applied for over fifty years by many different people including John Milnor, G. L. S. Shackle,[30] Daniel Ellsberg,[35] R. Duncan Luce and Howard Raiffa, in a field some date back to Jacob Bernoulli.[36]

The University of Minnesota, the College of Liberal Arts launched the Heller-Hurwicz Economics Institute, a new global initiative in the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota created to inform public policy by supporting and promoting frontier economic research and by communicating our findings to leading academics, policymakers, and business executives around the world. The Institute will be housed in our department. Funds raised by the Institute will be used to attract and retain preeminent faculty and, in part, to support graduate student research.

The University of Michigan has an endowed chair named for Hurwicz, the Leonid Hurwicz Collegiate Professor of Complex Systems, Political Science, and Economics, currently held by Scott E. Page.

The Leonid Hurwicz Distinguished Lecture is given to the Minnesota Economic Association (as is the Heller lecture). John Ledyard (2007), Robert Lucas, Roger Myerson, Edward C. Prescott, James Quirk, Nancy Stokey and Neil Wallace are among those who have delivered the lecture since it was inaugurated in 1992.[citation needed]

Nobel Prize in Economics

In October 2007, Hurwicz shared the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with Eric Maskin of the Institute for Advanced Study and Roger Myerson of the University of Chicago „for having laid the foundations of mechanism design theory.”[37] During a telephone interview, a representative of the Nobel Foundation told Hurwicz and his wife that Hurwicz was the oldest person to win the Nobel Prize. Hurwicz said, „I hope that others who deserve it also got it.” When asked which of all the applications of mechanism design he was most pleased to see he said welfare economics.[38] The winners applied game theory, a field advanced by mathematician John Forbes Nash, to discover the best and most efficient means to reach a desired outcome, taking into account individuals’ knowledge and self-interest, which may be hidden or private.[39] Mechanism design has been used to model negotiations and taxation, voting and elections,[3] to design auctions such as those for communications bandwidth,[24] elections and labor talks[39] and for pricing stock options.[40]

Unable to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm because of his poor health,[41][42] Hurwicz received the prize in Minneapolis. Accompanied by Evelyn, his spouse of six decades, and his family, he was the guest of honor at a convocation held on the campus of the University of Minnesota presided over by university president Robert Bruininks. Immediately following a live broadcast of the Nobel Prize awards ceremony, Jonas Hafstrom, Swedish ambassador to the United States, personally awarded the Economics Prize to Professor Hurwicz.[43]

Publications

- Hurwicz, Leonid (December 1945). „The theory of economic behavior”. The American Economic Review. American Economic Association via JSTOR. 35 (5): 909–925. JSTOR 1812602. Exposition on game theory classic.

- Hurwicz, Leonid (April 1946). „Theory of the firm and of investment”. Econometrica. The Econometric Society via JSTOR. 14 (2): 109–136. doi:10.2307/1905363. JSTOR 1905363.

- Hurwicz, Leonid (July 1947). „Some problems arising in estimating economic relations”. Econometrica. The Econometric Society via JSTOR. 15 (3): 236–240. doi:10.2307/1905482. JSTOR 1905482.

- Hurwicz, Leonid; Arrow, Kenneth J. (1953). Hurwicz’s optimality criterion for decision making under ignorance. Technical Report 6. Stanford University.

-

- Also available as: Hurwicz, Leonid; Arrow, Kenneth J. (1977). „Appendix: An optimality criterion for decision-making under ignorance”. (online book). Cambridge Books Online: 461–472. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511752940.015.

- and as: Hurwicz, Leonid; Arrow, Kenneth J. (1977), „Appendix: An optimality criterion for decision-making under ignorance”, in Arrow, Kenneth J.; Hurwicz, Leonid, Studies in resource allocation processes, Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 461–472, ISBN 9780521215220

- Hurwicz, Leonid (1960), „Optimality and informational efficiency in resource allocation processes”, in Arrow, Kenneth J.; Karlin, Samuel; Suppes, Patrick, Mathematical models in the social sciences, 1959: Proceedings of the first Stanford symposium, Stanford mathematical studies in the social sciences, IV, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, pp. 27–47, ISBN 9780804700214

- Hurwicz, Leonid (May 1969). „On the concept and possibility of informational decentralization”. The American Economic Review, special issue: papers and proceedings of the eighty-first annual meeting of the American Economic Association, (centralization and decentralization in economic systems). American Economic Association via JSTOR. 59 (2): 513–524. JSTOR 1823704.

- Hurwicz, Leonid; Arrow, Kenneth J. (1972), „Decision making under ignorance”, in Carter, C. F.; Ford, J. L., Uncertainty and expectations in economics: essays in honour of G.L.S. Shackle, Oxford / New York: Basil Blackwell / Augustus M. Kelley, ISBN 9780631141709.

- Hurwicz, Leonid (May 1973). „The design of mechanisms for resource allocation”. The American Economic Review, special issue: papers and proceedings of the eighty-fifth annual meeting of the American Economic Association, (Richard T. Ely Lecture). American Economic Association via JSTOR. 63 (2): 1–30. JSTOR 1817047.

- Hurwicz, Leonid; Radner, Roy; Reiter, Stanley (March 1975). „A stochastic decentralized resource allocation process: Part I”. Econometrica. The Econometric Society via JSTOR. 43 (2): 187–221. doi:10.2307/1913581. JSTOR 1913581. Cowles Commission Discussion Paper: Economics No. 2112, (pdf).

- Hurwicz, Leonid (May 1995). „What is the Coase Theorem?”. Japan and the World Economy. Elsevier. 7 (1): 49–74. doi:10.1016/0922-1425(94)00038-U.

- Hurwicz, Leonid; Reiter, Stanley (2008). Designing economic mechanisms. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521724104.

See also

References

- http://www.fau.edu/library/nobel90.htm

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Hurwicz.html

- Ohlin, Pia (15 October 2007). „US trio wins Nobel Economics Prize”. Agence France Presse. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Kuhn, Harold (introduction) (7 August 2007). „Sample Chapter for von Neumann, John & Morgenstern, Oskar. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (Commemorative Edition)”. Princeton University Press. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- Higgins, Charlotte (15 October 2007). „Americans win Nobel for economics”. BBC News. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Lohr, Steve (2007-10-16). „Three Share Nobel in Economics for Work on Social Mechanisms”. The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Hughes, Art (15 October 2007). „Leonid Hurwicz—commanding intellect, humble soul, Nobel Prize winner”. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- „A house resolution honoring Professor Leo Hurwicz on his 90th birthday”. Legislature of the State of Minnesota (image via University of Minnesota, umn.edu). 9 April 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Clement, Douglas (Fall 2006). „Intelligent Designer” (PDF). Minnesota Economics. Department of Economics, University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts: 6–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Horwath, Justin (16 October 2007). „U economics prof awarded Nobel Prize”. The Minnesota Daily. Archived from the original on 2008-01-06. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- „Perspectives on Leo Hurwicz, A Celebration of 90 Years (timeline)” (PDF). University of Minnesota (econ.umn.edu). 14 April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Leonid Hurwicz, oldest Nobel winner, dies, Minneapolis Star Tribune, June 25, 2008

- Leonid Hurwicz, oldest Nobel winner, dies at 90, New York Times, June 26, 2008

- „Five-Year Report, 1942–46, XII. Biographical and Bibliographic Notes”. Cowles Foundation, Yale University. 1942–1946. Archived from the original on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Chiacu, Doina (Reuters) (15 October 2007). „Russian-born U.S. economist oldest-ever Nobel winner”. Reuters Group. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- „Report for 1942”. Cowles Foundation, Yale University. 1942. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Simon, Herbert A. (28 September 1998) [1997]. An Empirically-Based Microeconomics (Raffaele Mattioli Lectures). Cambridge University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-521-62412-6.

- „Report for 1950–1951”. Cowles Foundation, Yale University. 1951. Archived from the original on 2007-06-25. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- „Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics: Staff Lists, 1955–Present”. Yale University. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- „Guide to the Leonid Hurwicz papers, 1911-2008 and undated”. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- „University of Minnesota Professor Leonid Hurwicz wins Nobel Prize in economics” (Press release). Regents of the University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- „Major Works of Leonid Hurwicz”. The history of Economic Thought. cepa.newschool.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- „Nobel Laureates”. Frequently Asked Questions. Nobelprize.org. 2007. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Morrison, Deanne (15 October 2007). „University professor wins Nobel Prize”. UMN News, Regents of the University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- „All Laureates in Economics”. Nobelprize.org. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Myerson, Roger B. (2007-02-28). Fundamental Theory of Institutions: A Lecture in Honor of Leo Hurwicz (pdf). University of Chicago. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-10-15.. Hurwicz Lecture originally presented at the North American meetings of the Econometric Society, at the University of Minnesota on 2006-06-22.

- Hurwicz, Leonid; Reiter, Stanley (22 May 2006). Designing Economic Mechanisms. Cambridge University Press. pp. Frontmatter (PDF) via Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83641-7. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- „Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter H” (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- „Academic Exchange with Foreign Institutions”. Huazhong University of Science and Technology School of Economics. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Zappia, Carlo; Basili, Marcello (May 2005). „Shackle versus Savage: non-probabilistic alternatives to subjective probability theory in the 1950s”. Quaderni. Università degli Studi di Siena, Dipartimento di Economia Politica (452). Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Jaffray, Jean-Yves; Jeleva, Meglena (16–19 July 2007). „Information Processing under Imprecise Risk with the Hurwicz criterion” (PDF). International Symposium on Imprecise Probability: Theories and Applications (conference proceedings via sipta.org). Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Luce, R. Duncan; Raiffa, Howard (1989) [1957 ISBN 0-471-55341-7]. Games and Decisions: Introduction and Critical Survey. Dover Publications via Amazon Reader, Look Inside. pp. xvii +304–305 per Ellsberg p. 180. ISBN 0-486-65943-7.

- Wald, Abraham (1950). Statistical Decision Functions. John Wiley & Sons.

- John Milnor credits Hurwicz with this idea. Straffin, Philip D. (5 September 1996). Game Theory and Strategy (New Mathematical Library). The Mathematical Association of America via Amazon Reader Search Inside. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-88385-637-9.

- Ellsberg, Daniel (2001). Risk, Ambiguity And Decision (Studies in Philosophy). New York, N.Y.: Garland Publishing via Amazon Reader, Search Inside. pp. xxii. ISBN 0-8153-4022-2.

- Kramer, Edna Ernestine (1982). The Nature and Growth of Modern Mathematics. Princeton University Press via Google Books limited preview. p. 290. ISBN 0-691-02372-7. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- „The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2007” (Press release). Nobel Foundation. October 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- „Leonid Hurwicz – Interviews”. Nobel Foundation. October 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- Tong, Vinnie (Associated Press) (15 October 2007). „U.S. Trio Wins Nobel Economics Prize”. Forbes.com. Forbes. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Bergman, Jonas; Kennedy, Simon (15 October 2007). „Hurwicz, Maskin and Myerson Win Nobel Economics Prize”. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- „Russian-born Nobel Prize winner lives in nursing home”. Russia Today. TV-Novosti. 19 October 2007. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Walsh, Paul (2007-12-10). „U professor to receive his Nobel Prize today”. Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- Art Hughes (2007-12-10). „Minnesota’s newest Nobel Laureate receives his prize”. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Leonid Hurwicz |

- Leonid Hurwicz Papers at Duke University

- Hurwicz Nobel Prize lecture

- Soumyen Sikdar, Leonid Hurwicz (1917–2008): A Tribute, Contemporary Issues and Ideas in Social Sciences, Vol 4, No 2 (2008)

- „Perspectives on Leo Hurwicz (conference program and photos)”. University of Minnesota (econ.umn.edu). 14 April 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Clement, Douglas (Fall 2006). „Intelligent Designer (cover story)” (PDF). Minnesota Economics. Department of Economics, University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts: 6–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- „Intelligent design”. The Economist. The Economist Group. 18 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- Cho, Adrian (15 October 2007). „The Economics Nobel: Giving Adam Smith a Helping Hand”. ScienceNOW Daily News. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Fonseca, Gonçalo L. (author and maintainer). „Major Works of Leonid Hurwicz, in Leonid Hurwicz, 1917–”. History of Economic Thought Website, The New School. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- Tabarrok, Alex (2007-10-16). „What is Mechanism Design? Explaining the research that won the 2007 Nobel Prize in Economics”. Reasononline news. Reason Magazine. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- Biography of Leonid Hurwicz from the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences

Leonid Hurwicz dostał nagrodę Nobla

Czytaj więcej na: http://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/leonid-hurwicz-dostal-nagrode-nobla

Szwedzka Akademia Nauk w Sztokholmie poinformowała w komunikacie, że teoria ta pozwala „odróżnić sytuacje, w których rynki funkcjonują dobrze od tych, w których rynki funkcjonują źle”. „Pomogła ona określić ekonomistom skuteczne mechanizmy rynkowe, schematy regulacji i procedury wyborów. Dziś +mechanism design theory+ odgrywa główną rolę w wielu dziedzinach ekonomii oraz w naukach politycznych” – podano. Leonid Hurwicz jest emerytowanym profesorem University of Minnesota w Minneapolis. Urodził się w 1917 r. w Moskwie. Jego rodzice byli Polakami. W 1938 r. ukończył studia prawnicze w Warszawie. Następnie studiował w: London School of Economics (1938- 1939), Institut des Hautes Etudes Internationales w Genewie (1939- 1940), na Harvardzie (1941) i na University of Chicago (1940- 1942). W 1994 przyznano mu doktorat honoris causa Szkoły Głównej Handlowej w Warszawie. Dwaj Amerykanie – Eric S. Maskin i Roger B.Ryerson – rozwijali „mechanism design theory”. Maskin, urodzony w 1950 r., pracuje w Institute for Advanced Study w Princeton. Ryerson, urodzony w 1951 r., pracuje na University of Chicago. Maskin zajmował się m.in. teorią gier, teorią aukcji, a także porównywaniem ordynacji wyborczych. Ryerson także pracuje nad teorią gier, również modelami decyzji ekonomicznych. Prof. Maria Podgórska, dyrektor Instytutu Ekonometrii SGH powiedziała PAP, że prof. Hurwicz ma bardzo szerokie zainteresowania. „Ekonometria w każdym sensie, również ekonomia matematyczna. W latach 90-tych, kiedy w Europie Środkowej zaczęły się przemiany, bardzo interesował się modelowaniem transformacji” – podkreśliła. Jak napisał Wojciech Maciejewski z Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego w ocenie dorobku naukowego Hurwicza w związku z rozpoczęciem procedury nadania doktoratu honoris causa SGH, w początkowym okresie zainteresowania naukowe prof. Hurwicza skupiały się wokół różnych teoretycznych problemów ekonometrii. Był on m.in. w latach 1944-46 współpracownikiem grupy badaczy modelowania ekonometrycznego, która stworzyła podstawy nowoczesnej ekonometrii, tak zwanej Cowles Commission. Drugi nurt badań dotyczy różnych zagadnień optymalizacji decyzji w zagadnieniach ekonomicznych. Hurwicz zajmował się teorią programowania matematycznego i teorią gier, teorią optymalnych decyzji, teorią równowagi ogólnej, teorią popytu, konsumpcji i dobrobytu, teorią cen, teorią rozwoju i planowania. Badał również kwestie decentralizacji i efektywności systemów ekonomicznych oraz procesów alokacji zasobów. Publikował prace nt. teoretycznych i praktycznych zagadnień transformacji instytucjonalno-gospodarczych i rozwoju, w tym nt. przekształceń własnościowych w Polsce – pisał prof. Juliusz Kotyński z SGH.

Czytaj więcej na: http://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/leonid-hurwicz-dostal-nagrode-nobla

Leonid Hurwicz – Biographical

This text is adapted from „Leonid Hurwicz’s Game”, by Ann Bauer. Reprinted with permission from the author and Twin Cities Business magazine.

Professor Hurwicz says that he is simply a product of his history. He knows from experience how circumstances change when people don’t abide by the rules of the game.

„I cannot tell you my life story and what I did without telling you about politics as well,” Hurwicz says.

Leonid Hurwicz was born in Moscow on August 21, 1917 after the Kirensky revolution but before the October Bolshevik revolution. In early 1919, he and his family returned to Warsaw − his father’s home; his mother was also Polish − after the Communists came to power in Russia. „My father was convinced, I think rightly, that if he stayed in Russia, he would have trouble with Lenin,” Hurwicz says. „Of course, that’s not my memory; I was 14 months old. But I know we traveled in various imperfect ways, such as horse-drawn wagon, to arrive in Poland.”

His father was a lawyer, with a degree from the Sorbonne in Paris. In Warsaw a five-year internship was required to practice law, so he taught history while completing that. Hurwicz’s mother was a teacher as well, but after the move she stayed home with him and his younger brother, giving them lessons in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Hurwicz didn’t begin formal schooling until the age of nine, when he started at a private institution attended and staffed mostly by Jews.

It was a time of pogroms throughout Europe. Though he and his family were not swept up in anything so frightening, Hurwicz does recall strange, random attacks. One year, the university in Warsaw decided the Jewish community had not contributed its share of corpses to the medical school. When a group tried to force Jewish students to sit in a segregated section of their classrooms, the university rector failed to intervene. The Jewish students, including Leo, stood in the back of the room for the entire year in protest. The protest succeeded and the following year Jewish students were seated again.

„I experienced harassment during this period.” Hurwicz pauses, as if remembering. „But I never was beaten or attacked personally. And with my professors, I felt no discrimination.”

He graduated from Warsaw University in 1938 with a degree in law, originally intending to follow in his father’s footsteps. However, beginning in his second year of law school, he’d taken some obligatory economics courses and became more interested in this discipline than any other.

„I had the belief that many troubles you could observe on the European continent were due to politicians not understanding economic phenomena,” Hurwicz says. „Even if they had good intentions, they didn’t have the skills to solve problems.”

Hitler was in power in Germany and Jews all across Eastern Europe were on guard − made to feel like intruders in their own countries, hearing hideous rumors about persecution they could not fathom but nevertheless feared. Hurwicz’s father, sensing the changing tides, suggested that his older son apply to the London School of Economics rather than set up a law practice at home.

Leo went to London in the fall of ’38, but in the Spring of ’39 the British refused to extend his visa. So Hurwicz went to France and then Switzerland on a transit visa. He arrived in Bern in August of 1939 − less than a week before Germany attacked and occupied western Poland, including Warsaw. Hurwicz heard the news, but didn’t know that his parents and brother had managed to escape to Russian occupied eastern Poland. By the spring of 1940, they had been arrested and taken to a labor camp in Arctic European Russia. He spent months in Geneva, enrolled part time as a student, living off what little money he had left, and hoping for news of his family.

Hurwicz contacted his cousins in Chicago, whom his parents had told him would help if he needed to leave. In 1940, 23 years old and all alone in the world but for some cousins he’d never met who wired money and an address, Hurwicz booked passage on an Italian boat.

„In a month − no less − Mussolini joined Hitler,” Hurwicz recalls. His ticket was now worthless because no Italian ship could enter American ports. „That was bad luck for me, because there was the question of how to get my money back. Also, even if I had money, how did I travel from Switzerland to some city which was not on Hitler’s side and could get me to America?”

He found a way. An airline opened briefly between Switzerland and Barcelona, both neutral cities. Hurwicz was able to fly to Spain and take a train to Madrid, then Lisbon. He spent almost two months in the Portuguese city of Estoril which was „like Monte Carlo,” tutoring the children of wealthy Spanish and French families vacationing there. Then Hurwicz got word of a Greek boat, the Nea Hellas, sailing for New Jersey.

Leo needed help getting his money back from the Italian company, so he went to the harbormaster who said „What can I do?”. Leo suggested that the harbormaster could threaten to take the company’s license away, and that if he didn’t succeed, he would have Hurwicz on his hands for the duration of the war. The harbormaster followed Leo’s suggestion. With a refund and the little he had earned tutoring, Hurwicz booked passage on the Greek boat.

In Chicago, he lived with his cousins deep in the Polish section of town − sleeping on their couch and auditing courses at the University of Chicago with the famous economist Ludwig von Mises. Finally, he got an offer of a job at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology „from someone who is very well known: Paul Samuelson. The job was as a teaching and research assistant for only one semester − a term no self-respecting graduate student would accept,” Hurwicz says. „But I had no other offers. In fact, it was a miracle I had this one.”

He moved to Massachusetts and began working under Samuelson, who would win the Memorial Prize for economics in 1970. At MIT, Hurwicz tested a hypothesis about how businesses arrive at prices for their goods and services. He returned to Chicago in mid-June 1941, by now a more desirable candidate for academic appointment.

Again, world events dictated his course.

więcej u źródła: https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/2007/hurwicz-bio.html

Rzeczpospolita 2013 – Leonid Hurwicz, noblista z Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego

http://www.rp.pl/artykul/925873-Leonid-Hurwicz–noblista-z-Uniwersytetu-Warszawskiego.html

5 lat temu zmarł Leonid Hurwicz, laureat nagrody Nobla w dziedzinie ekonomii w 2007 roku, absolwent Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego (ur. w 1917 roku)

90-letni Leonid Hurwicz i młodsi od niego o ponad 30 lat dwaj inni uczeni amerykańscy – Eric S. Maskin i Roger B. Myerson – otrzymali w 2007 roku nagrodę za badania nad teorią mechanizmów rynkowych (ang. mechanism design theory). Najstarszy z tej trójki za ich zapoczątkowanie, a młodsi ekonomiści za rozwijanie teorii. Fundamenty pod nagrodzoną koncepcję Leonid Hurwicz, emerytowany profesor Uniwersytetu Minnesota, położył w latach 60. Hurwicz zauważył, że zdefiniowana przez Adama Smitha niewidzialna ręka rynku nie działa doskonale. Nie zawsze ceny transakcji osiągają poziom optymalny, bo rynki nie są w pełni konkurencyjne. Decydując się na zawarcie transakcji, nie mamy pełnej informacji o tym, jak inni oferenci czy klienci wyceniają dany produkt. Szczególnie zaciemniony obraz jest tam, gdzie do wymiany dochodzi między osobami prywatnymi. Modelowym przykładem takiej sytuacji jest transakcja sprzedaży pianina. Załóżmy, że sprzedawca Erika nie wie, jak inni wyceniają ten instrument. Nie wie tego również potencjalny nabywca Piotr. Ale Erika wie, że zadowoli ją cena nie niższa niż X. A Piotr nie chce zapłacić więcej niż Y. Do transakcji dojdzie oczywiście tylko wtedy, gdy poziom X jest wyższy od Y. Obie osoby chciałyby jednak zmaksymalizować swoje zyski. A więc Erika dąży do ceny maksymalnie przewyższającej X, a Piotr do ceny możliwie niskiej w porównaniu ze swoim Y. Oboje nie wiedzą, jaki docelowy poziom wyznaczył sobie kontrahent. Zasługą badaczy jest nie tylko zanalizowanie niedoskonałych sytuacji, ale też zaproponowanie sposobów zachowania. Fakt, że rynek nie jest doskonały, nie oznacza, że powinniśmy go zastąpić innym mechanizmem. W przypadku muzycznej transakcji najlepsza byłaby dwustronna aukcja, czyli i Erika, i Piotr podawaliby swoje kolejne propozycje cenowe. Efektem takiej aukcji powinna być cena znajdująca się w równej odległości między X i Y. Dla innych sytuacji, na przykład monopolu, ekonomiści, posiłkując się mechanizmem teorii planowania, znaleźli inne strategie cenowe. Teoria sformułowana początkowo przez Hurwicza pokazuje także, dlaczego nie zawsze rynek zadziała. W przypadku dóbr publicznych, takich jak czyste powietrze czy obrona narodowa, nie warto liczyć na kapitalistyczne reguły. Bo każdy będzie udawał, że wcale mu tak bardzo nie zależy na czystym powietrzu czy bezpiecznych granicach, z nadzieją, iż sfinansują to inni. Na rynku nie ukształtuje się zatem cena odzwierciedlająca faktyczne pragnienia ludzi. Wtedy musi wkroczyć państwo i opodatkować obywateli. Komitet Noblowski podkreślił, że teoria amerykańskich ekonomistów pomaga odróżnić rynki funkcjonujące efektywnie od tych niedoskonałych. Na jej podstawie można budować modele matematyczne szacujące ceny w warunkach informacji rozproszonej na wiele jednostek, producentów i konsumentów. „Teoria pomogła ekonomistom opracować skuteczne mechanizmy wyceny, regulacje rynkowe, a nawet procedury głosowania” – uzasadnia komitet noblowski. W nagrodzie wystąpił wątek polski. Jej najstarszy laureat pochodził z rodziny polskich Żydów. Urodził się co prawda w Moskwie w 1917 roku, ale studiował już na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim. Wojna zastała go w Londynie, potem wyemigrował do USA. W latach 90. otrzymał tytuł doktora honoris causa Szkoły Głównej Handlowej.

|

|

|

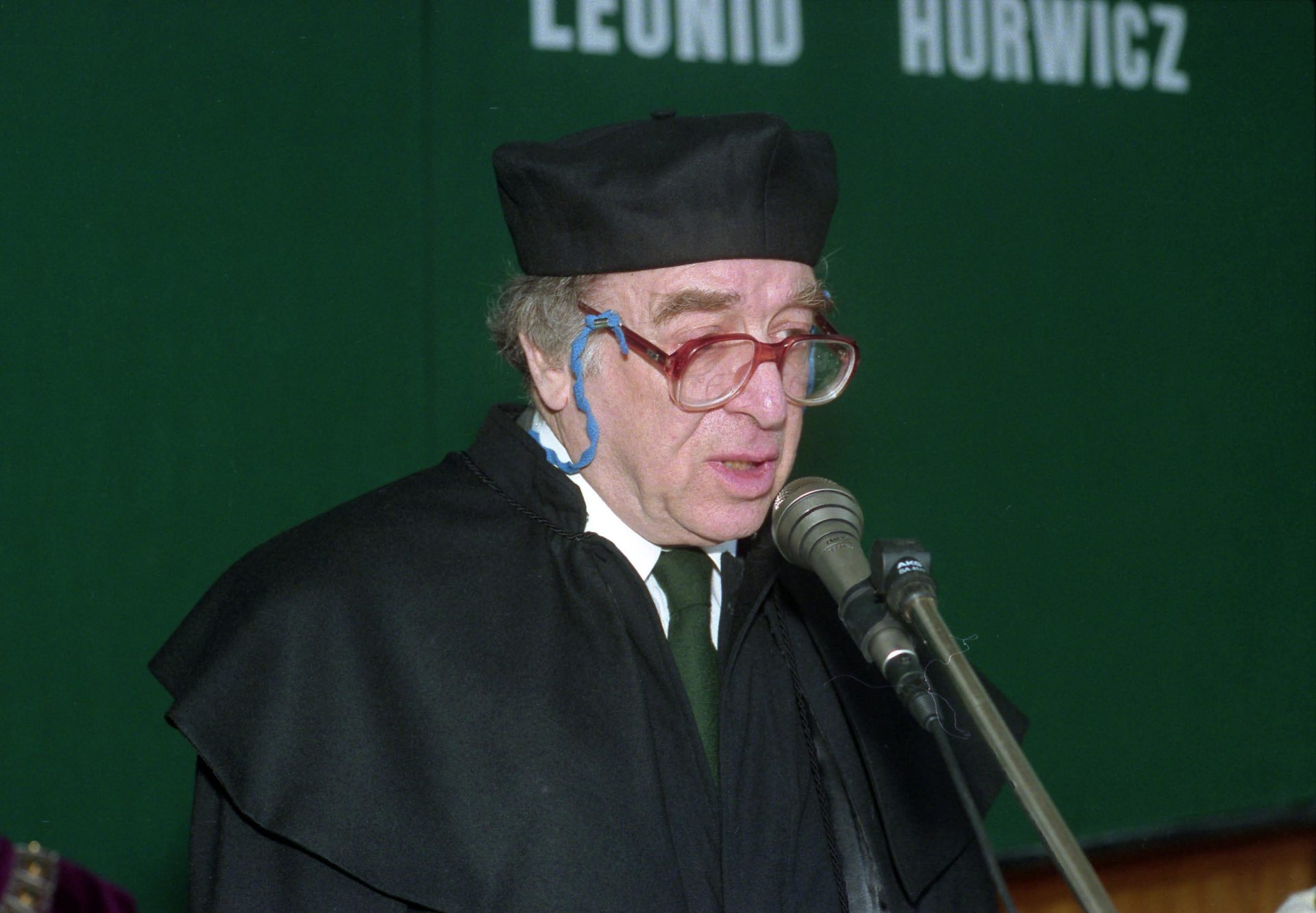

W 1994 r. SGH przyznała tytuł doktora honoris causa Profesorowi Janowi Drewnowskiemu. Profesor Tadeusz Kowalik w opinii o dorobku naukowym Profesora Drewnowskiego napisał m.in.: „Trwałym osiągnięciem Drewnowskiego pozostają indykatory społeczne. Dzięki nim potrafił On rzeczywiście dokonać znacznego przybliżenia teorii ekonomii do rzeczywistości… Drewnowski, paradoksalnie, wniósł sporo do naszej wiedzy o kolektywistycznym państwie i jego preferencjach społecznych”. W tym samym roku tytuł doktora honoris causa SGH otrzymał Profesor Leonid Hurwicz, późniejszy laureat Nagrody Nobla 2007 w dziedzinie ekonomii. Promotorzy i recenzenci w przewodzie podkreślali osiągnięcia Profesora Hurwicza w zakresie: ekonometrii, głównie teorii programowania matematycznego i teorii gier, teorii równowagi ogólnej i efektywnych systemów ekonomicznych oraz transformacji instytucjonalnej 13 kwietnia 1994 roku, podczas po raz pierwszy obchodzonego w SGH Święta Szkoły, odbyła się uroczystość nadania tytułu doktora honoris causa Profesorowi Janowi Drewnowskiemu i Profesorowi Leonidowi Hurwiczowi.

|