Wielcy Polacy – Stanisław Marcin Ulam (1909 – 1984) i jego Orion

Stanisława Marcina Ulama przedstawia się zwykle jako współtwórcę bomby atomowej. Tymczasem jest on wynalazcą zaawansowanego napędu rakietowego działającego na zasadzie pulsacyjnych udarów jądrowych, a więc silnika jądrowego do rakiet kosmicznych. Możliwość zastosowania w praktyce tych silników zastopował układ USA – ZSRR o zaprzestaniu nadziemnych prób jądrowych. Gdyby nie to doczekalibyśmy się już dawno rakiet kosmicznych o napędzie nuklearnym.

Stanisława Marcina Ulama przedstawia się zwykle jako współtwórcę bomby atomowej. Tymczasem jest on wynalazcą zaawansowanego napędu rakietowego działającego na zasadzie pulsacyjnych udarów jądrowych, a więc silnika jądrowego do rakiet kosmicznych. Możliwość zastosowania w praktyce tych silników zastopował układ USA – ZSRR o zaprzestaniu nadziemnych prób jądrowych. Gdyby nie to doczekalibyśmy się już dawno rakiet kosmicznych o napędzie nuklearnym.

Wikipedia:

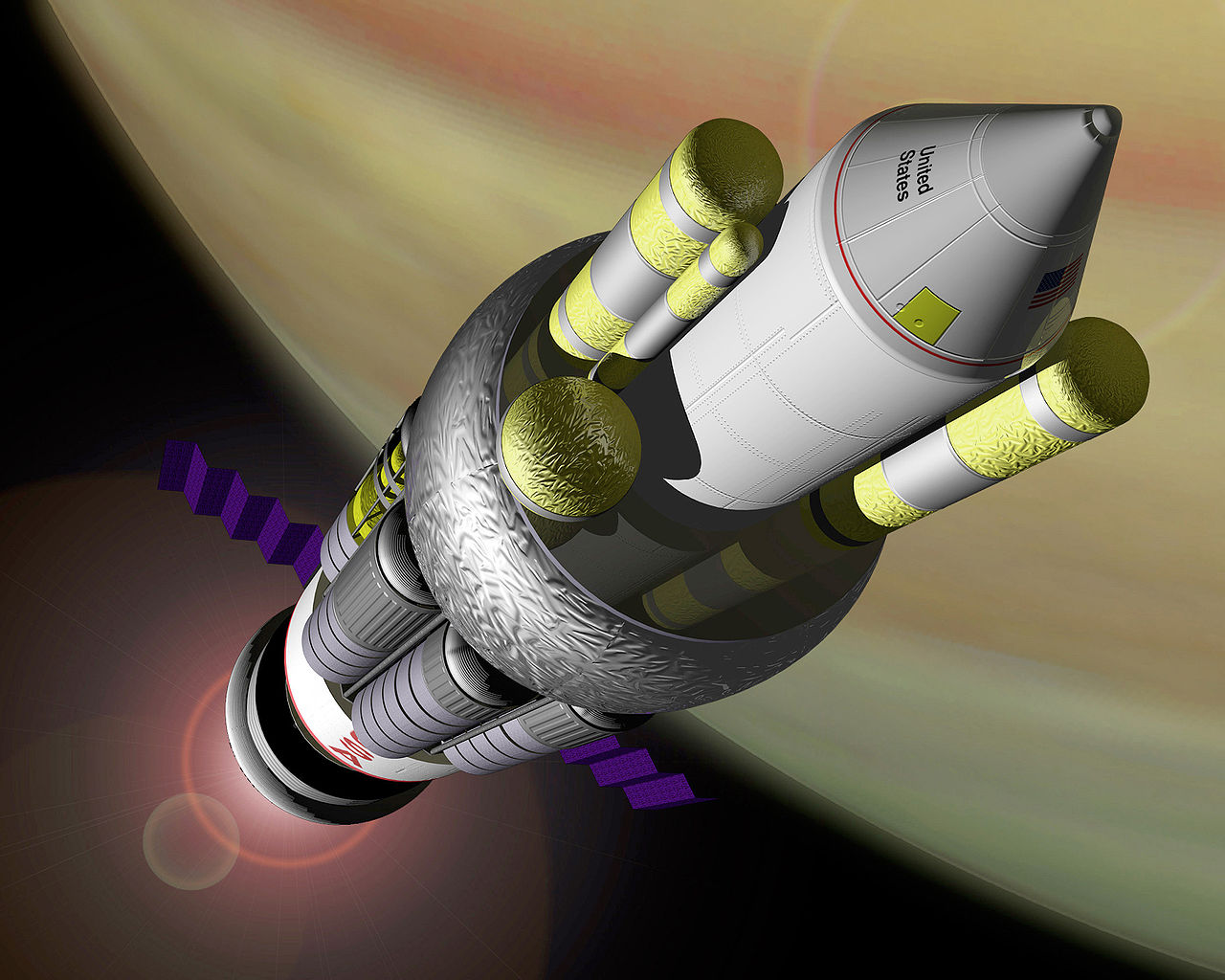

Program Orion

– amerykański program budowy rakiet nośnych o napędzie nuklearnym, oparty na koncepcji jądrowego napędu pulsacyjnego, opracowanego w 1955 roku przez współtwórców bomby wodorowej, Stanisława Ulama i Corneliusa Everetta.

Jądrowy napęd pulsacyjny

Napęd pulsacyjny w swoich założeniach pozwalał na wykorzystanie energii jądrowej do napędu pojazdów kosmicznych przy minimalnych nakładach projektowych. Projekt zakładał napędzanie pojazdu przez bomby atomowe wyrzucane z rufy pojazdu i detonowane w pewnej odległości za statkiem. Otaczająca bombę woda lub wosk (możliwe byłoby również zgromadzenie całej substancji napędowej w obrębie bomby) w chwili detonacji tworzyłyby wysokoenergetyczną plazmę, która uderzając w płytę na rufie pojazdu popychałaby go naprzód.

System zakładał wyposażenie pojazdu w potężne dwustopniowe mechaniczne amortyzatory, oraz umieszczone na samej płycie poduszki powietrzne, które rozkładałaby w czasie wynikające z powtarzających się uderzeń plazmy, trwające milisekundy, ruchy płyty, na trwające sekundy ruchy pojazdu, ograniczając przeciążenia do możliwych do zniesienia przez konstrukcję pojazdu oraz pasażerów (zakładane 1 – 3G). Na podstawie konstrukcji atomowych zapalników do ładunków termojądrowych (konstrukcja bomby termojądrowej typu Ulama – Tellera) opracowano koncepcję atomowych ładunków napędowych, w których ładunek termojądrowy zastąpiono by warstwą boru, lub polietylenu, otoczonymi odpowiednio ukształtowanym opakowaniem z wolframu.

W trakcie eksplozji ładunku rozszczepialnego opakowanie to ogniskowałoby strumień neutronów i promieniowania X – w odróżnieniu jednak od bomby typu Ulama – Tellera nie na ładunku termojądrowym, lecz na ww. warstwie polietylenu lub boru – powstałaby w ten sposób wysokotemperaturowa plazma o kształcie cygara która po przebyciu kilkudziesięciu metrów rozprężyłaby się i ostygła do ok. 14 tys. stopni C. Po uderzeniu w płytę napędową następowałaby gwałtowna (ok. 0,3 milisekundy) rekompresja plazmy i wzrost jej temperatury do ok. 40 tys. stopni C. Przy tak wysokich temperaturach plazma emituje głównie promieniowanie ultrafioletowe, które słabo przenika przez samą plazmę oraz materiał tarczy, co tłumaczy dlaczego tarcza nie ulegałaby stopieniu ani wyparowaniu (potwierdziły to eksperymenty Plumbbomb, oraz eksperymenty ze stalowymi kulami umieszczanymi w odległości kilkudziesięciu metrów od eksplodujących ładunków jądrowych – kule znajdowano nienaruszone – patrz poniżej). Płyta napędowa mogłaby być wykonana ze zwykłej stali lub nawet aluminium. Obliczono że po każdej eksplozji wyparowałoby jedynie ok. 1 mm powierzchni płyty. Jeden z mózgów programu – genialny fizyk i matematyk Freeman Dyson obliczył jednak, że zetknięcie plazmy z materiałem parującym z płyty napędowej mogłoby powodować powstanie turbulencji, które niebezpiecznie rozgrzałyby płytę (efekt konwekcji) w związku z tym na płytę natryskiwano by ww. wosk, olej, grafitowy smar lub wodę – chodzi o to, że węgiel lub wodór zawarte w ww. substancjach bardzo silnie pochłaniają promienie ultrafioletowe, co wyeliminowałoby parowanie płyty.

Kolejny problem stanowiło szybkie umieszczenie ładunków kilkadziesiąt metrów od płyty (w początkowej fazie lotu ok. 4 ładunki na sekundę) – rozwiązano by go po prostu poprzez zastosowanie działa wystrzeliwującego ładunki przez otwór w płycie – pod pojazd (w latach 50. skonstruowano jądrowe pociski artyleryjskie). Początkowo obawy budziło niezbyt precyzyjne umieszczanie ładunków pod płytą – obawiano się braku stabilności lotu, jednak Freeman Dyson obliczył, że przy większej liczbie ładunków wynikające z tego odchylenia lotu uśredniają i znoszą się (potwierdził to stabilny lot modelu pojazdu napędzanego chemicznymi ładunkami wybuchowymi – na wysokość 180 m).

W projekcie uderza prostota zastosowanych rozwiązań, solidność konstrukcji, zastosowanie zwykłego aluminium i stali w odróżnieniu od supermateriałów stosowanych w klasycznych pojazdach kosmicznych (projektanci jako wykonawcę projektu rekomendowali firmę Electric Boat Company zajmującą się budową okrętów podwodnych), niemożliwe przy innych systemach napędowych osiąganie jednocześnie wysokiej siły ciągu i wysokiej wydajności napędu, oraz wynikające z natury jądrowych ładunków wybuchowych (im silniejsze tym wydajniejsze) wzrost wydajności konstrukcji, oraz prostoty jej wykonania – w miarę wzrostu wymiarów pojazdu. Obliczono, że zarówno dla pojazdu o masie 2000 ton (wersja międzyplanetarna) jak i Super-Oriona o masie 8.000.000 ton (wersja międzygwiezdna napędzana ładunkami termojądrowymi – mogąca osiągnąć 10% prędkości światła) różnica kosztu jądrowych ładunków napędowych nie byłaby zbyt duża. Ze względu na olbrzymią masę i ładowność pojazdów (wersja międzyplanetarna mogłaby odbywać podróże w tę i z powrotem z ładunkiem użytecznym stanowiącym ok. 50% masy własnej – w porównaniu rakiety chemiczne ok. 5% – w jedną stronę i 5% z tych 5% z powrotem) pomimo wysokiej ceny jądrowych ładunków napędowych (większość kosztów realizacji programu Orion) – koszt wyniesienia kilograma ładunku (w przeliczeniu na ceny z 2005 r.) na niską orbitę okołoziemską stanowiłby kilka- kilkadziesiąt dolarów dla wersji międzyplanetarnej i ok. 30 centów dla Super Oriona (w porównaniu do kilku- kilkudziesięciu tysięcy dolarów dla chemicznego napędu rakietowego).

Ze względu na zanieczyszczenie radiologiczne wywoływane przez serię eksplozji jądrowych, starty odbywałyby się z istniejących poligonów jądrowych. Jako że większość odpadów radioaktywnych związane jest z zasysaniem i napromieniowaniem pyłu z powierzchni ziemi przez kulę ognistą wybuchu jądrowego start odbywałby się z wysokich na kilkadziesiąt metrów wież. Podczas startu pojazd napędzałyby odpalane co sekundę bomby o mocy 0,1 kilotony. Wraz ze wzrostem prędkości i wysokości zastąpiłyby je odpalane znacznie rzadziej ładunki o mocy 20 kiloton. Innymi rozwiązaniami tego problemu byłby start z wyłożonej stalą i grafitem niecki (minimalizacja cyrkulacji powietrza)lub oceanicznej platformy startowej. Dalszą redukcję zanieczyszczenia atmosfery można by osiągnąć stosując start z okolic polarnych (naładowane radioaktywne cząstki uciekłyby w przestrzeń kosmiczną przez dziurę w magnetosferze) lub stosowanie w trakcie wznoszenia czystych ładunków atomowych (np. o typie bomby neutronowej – ok. tysiąckrotna redukcja zanieczyszczeń). Jak podkreślają zwolennicy tego typu napędu byłoby to znacznie mniej niż napromieniowanie atmosfery przez emisję radioaktywnych popiołów z elektrowni opalanych węglem – do produkcji paliwa dla jednego startu wahadłowca.

Historia programu

W trzy lata po opublikowaniu opracowania Ulama i Everetta firma General Atomics rozpoczęła prace nad zastosowaniem napędu pulsacyjnego w lotach kosmicznych. Programowi, kierowanemu przez dwóch fizyków – Theodora Taylora i Freemana Dysona, nadano kryptonim Orion. Program miał stanowić bezpośrednią konkurencję dla opracowywanych przez zespół von Brauna nośnych rakiet chemicznych – twórcy programu Orion wierzyli, że ich program pozwoliłby na wyniesienie na orbitę tysięcy ton ładunku przy kosztach porównywalnych ze znacznie mniej efektywnymi rakietami chemicznymi. Kres programowi położyły nie problemy techniczne, lecz brak woli politycznej, oraz traktat o zakazie testów jądrowych na ziemi, w powietrzu i w przestrzeni kosmicznej z 1963 r. (w trakcie negocjacji pojawiły się trudności odnośnie porozumienia z ZSRR co do definicji próby jądrowej) – jego kuriozalne w niektórych miejscach sformułowania np. jako uzasadnienie – obawa przed zanieczyszczeniem promieniowaniem próżni kosmicznej (wypełnionej przecież radioaktywnymi cząstkami promieniowania kosmicznego, promieniowaniem X i gamma z rozbłysków słonecznych, i z łatwością rozpraszającej każdą ilość substancji – poprzez swój bezmiar – o czym wiedzieli nawet ówcześni specjaliści (obliczono że produkty eksplozji nuklearnej w kosmosie zostaną np. wymiecione poza układ słoneczny przez cząstki wiatru słonecznego) pozwalają podejrzewać że chodziło o coś innego niż szczytna troska o środowisko. Ostatnio jednak pojawiają się spekulacje, że ze względu na prostotę i niezwykłą atrakcyjność projektu (pozwala na ekonomiczną eksploatację zasobów układu słonecznego), jest tylko kwestią czasu kiedy zrealizuje go jakieś państwo/państwa posiadające broń jądrową, które nie podpisały ww. traktatu (Chiny, Indie, Pakistan).

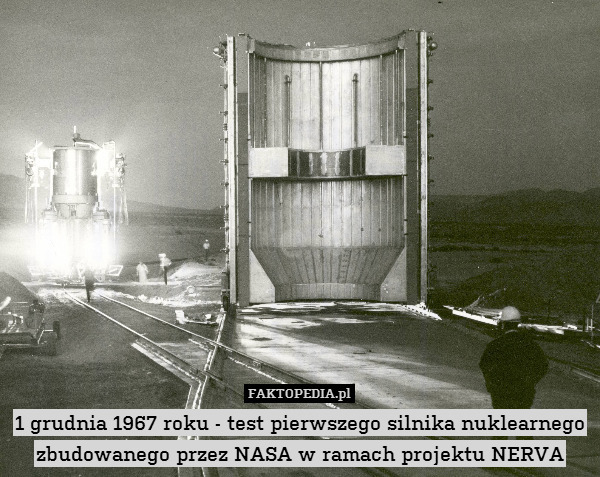

Testy

Koncepcja programu Orion była częściowo oparta na wynikach testów przeprowadzanych podczas wczesnych prób bomb atomowych na poligonie Eniwetok. Podczas testów stalowe kule pokryte powłoką grafitową zawieszano 30 stóp (ok. 9 metrów) nad centrum eksplozji jądrowej. Kule znajdowano w nienaruszonym stanie z częściowo odparowaną powłoką grafitu.

W ramach programu Orion wybudowano serię modeli mających przetestować czy aluminiowa płyta jest w stanie przetrwać wysokie temperatury i ciśnienie spowodowane odpaleniem w jej pobliżu konwencjonalnych materiałów wybuchowych. Po kilku nieudanych próbach udało się przeprowadzić stabilny lot – urządzenie osiągnęło maksymalną wysokość 100 metrów.

Jedyną weryfikację możliwości wykorzystania bomb jądrowych do wynoszenia ładunków na orbitę zapewnił wypadek podczas serii testów ograniczania zasięgu eksplozji jądrowych w ramach programu Operation Plumbbob. W 1957 roku bomba jądrowa niskiej mocy spowodowała wyrzucenie 900-kilogramowej stalowej pokrywy. Obliczenia wskazują, że płyta osiągnęła prędkość co najmniej dwukrotnie większą od prędkości ucieczki (według innych obliczeń – nawet sześciokrotnie większą). Najprawdopodobniej nie opuściła jednak ziemskiej atmosfery i wyparowała na skutek tarcia.

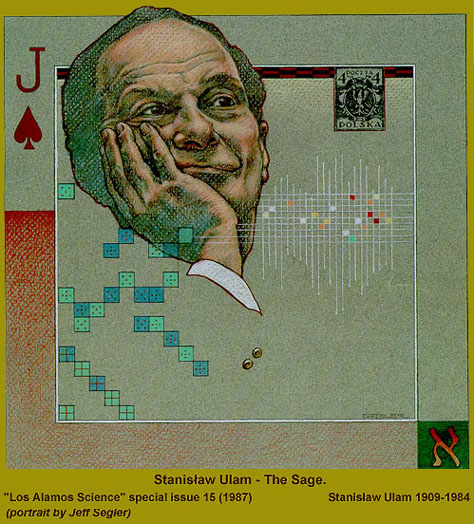

Stanisław Marcin Ulam

(ur. 13 kwietnia 1909 we Lwowie, zm. 13 maja 1984 w Santa Fe) – polski i amerykański matematyk (w 1943 przyjął obywatelstwo amerykańskie), przedstawiciel lwowskiej szkoły matematycznej. Współtwórca amerykańskiej bomby termojądrowej.

Ulam ma wielkie dokonania w zakresie matematyki i fizyki matematycznej w dziedzinach topologii, teorii mnogości, teorii miary, procesów gałązkowych. Ulam był także twórcą pierwszych metod numerycznych, np. metody Monte Carlo. Był też jednym z pierwszych naukowców, którzy wykorzystywali w swych pracach komputer. Metody komputerowe zostały użyte przez Ulama do modelowania powielania neutronów oraz rozwiązania problemu drgającej struny, zawierającej element nieliniowy (układ oscylujący Fermiego-Pasty-Ulama).

Urodzony w zamożnej, zasymilowanej rodzinie żydowskiej, już jako dziecko wykazywał wybitne zdolności. Jako uczeń wykształcił głębokie zainteresowanie matematyką. Po ukończeniu liceum, za namową rodziny, zdecydował się rozpocząć studia inżynierskie na Wydziale Ogólnym Politechniki Lwowskiej. Jednym z jego wykładowców był Stefan Banach. W czasie studiów jednakże więcej uwagi poświęcał uczęszczaniu na seminaria matematyki niż kursy inżynierskie. W wieku dwudziestu lat opublikował, za namową Kazimierza Kuratowskiego, w Fundamenta Mathematicae swoją pierwszą pracę[2], która dotyczyła arytmetyki liczb kardynalnych. Ostatecznie studia skończył jako matematyk, broniąc w 1934 doktorat. Już w czasie studiów stał się ważną postacią w bardzo prężnym środowisku lwowskich matematyków, do którego należeli także Stefan Banach, Hugo Steinhaus, Stanisław Mazur, Karol Borsuk, Kazimierz Kuratowski i wielu innych (tzw. lwowska szkoła matematyczna)[3].

Po zakończeniu studiów, nie mając większych szans na podjęcie pracy dydaktycznej, wyruszył w dłuższą podróż do Zachodniej Europy. Odwiedził ośrodki akademickie w Szwajcarii, Francji (Uniwersytet Paryski) i Anglii (Cambridge University). Wszędzie zdobywał sławę jako doskonały i oryginalny matematyk, pełny nowatorskich pomysłów. W czasie podróży nie tylko dał się poznać, lecz też poznawał kwiat naukowej elity starego kontynentu.

W 1935 Ulam otrzymał zaproszenie do Stanów Zjednoczonych do Princeton University. Po rocznym pobycie na tym uniwersytecie dostał propozycję pracy na Harvardzie, z której skorzystał. W tym czasie każde wakacje spędzał w Polsce. Ostatni jego pobyt w rodzinnym Lwowie miał miejsce latem 1939. Do USA wrócił późnym latem, zabierając ze sobą brata Adama, który rozpoczął studia na Harvardzie, by w przyszłości zostać sowietologiem. W 1941, Stanisław Ulam rozpoczął pracę jako profesor na Uniwersytecie Stanowym w Wisconsin. Tam też ożenił się ze stypendystką z Francji studiującą literaturę angielską – Françoise.

Najważniejszym i najbardziej twórczym w życiu Ulama był okres, w którym pracował w ramach Projektu Manhattan w ośrodku badań jądrowych w Los Alamos. Ulam przyjął obywatelstwo amerykańskie w 1943[4]. Z kilkoma przerwami, w czasie których przyjmował zaproszenia do wygłoszenia wykładów w najbardziej prestiżowych uczelniach amerykańskich, pracował w tym ośrodku od 1943 do 1967. Ulam należał do grupy opracowującej teorię konstrukcji bomby wodorowej. Ulam najpierw stosując swe innowacyjne metody matematyczne dowiódł, że koncepcja obrana przez kierownika projektu była błędna, a następnie zaproponował własne rozwiązanie, które doprowadziło projekt do sukcesu. Bomba tej konstrukcji nosi nazwę projektu Tellera-Ulama, od jej twórców węgierskiego fizyka Edwarda Tellera i Stanisława Ulama. Dokumenty z tamtego okresu są ciągle utajnione, więc jego wkład w ogólne dzieło pozostaje mało znany.

W czasie pracy w Los Alamos Ulam miał okazję współpracować z wybitnymi uczonymi – byli wśród nich John von Neumann, Enrico Fermi, George Gamow, Richard Feynman, Robert Oppenheimer.

Po zakończeniu pracy w Los Alamos objął stanowisko dziekana wydziału matematyki na Uniwersytecie Kolorado, pozostając jednocześnie konsultantem rządowym.

Zmarł nagle w Santa Fe na atak serca. Żona pochowała jego prochy na Cmentarzu Montmartre w Paryżu[5].

Ulam był autorem i współautorem wieluset publikacji naukowych. Wydał też kilka książek.

- Collection of Mathematical Problems, Nowy Jork 1960

- Sets, Numbers and Universes, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1974

- Mathematic and Logic (wspólnie z Markiem Kacem Nowy Jork 1986)

- The Scottish Book: A Collection of Problems (amerykańskie wydanie Księgi Szkockiej, słynnego notatnika przechowywanego w kawiarni Szkockiej we Lwowie, w którym notowano dyskusje prowadzone przez matematyków lwowskich.) Los Alamos 1957[6]

- Adventures of a Mathematician – biografia Berkeley, Kalifornia 1976. Polskie wydanie „Przygody matematyka”, Warszawa 1996.

- macierz Ulama

- spirala Ulama

- twierdzenie Borsuka-Ulama

- twierdzenie Mazura-Ulama

Czytajcie także:

MEDRZEC WIEKSZY NIZ ZYCIE

STANISLAW ULAM

http://www.zwoje-scrolls.com/zwoje16/text03.htm

In May 1999 the fifteenth anniversary occurs of the death of Stanislaw M. Ulam (born and educated in Lvov, the then Poland), one of the great geniuses of the contemporary Science.

I have endeavored to write (in Polish) an unchronological essay on Stanislaw Ulam, based on his autobiography, Adventures of a Mathematician (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1976), and the materials from two issues of Los Alamos Science (15/1987 and 3/1982) and on some additional information from Professor Gian-Carlo Rota of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

I am deeply indebted to the Editors of Los Alamos Science, Nikki Cooper in particular, for the information, mails and for their kind permission to use in Zwoje („The Scrolls”) the materials, i.e. the texts and the photographs published in Los Alamos Science Nos. 15/1987 (a special issue, devoted entirely to Stanislaw Ulam and his scientific legacy), 3/1982 and 21/1993. I am also grateful to Professor Gian-Carlo Rota of MIT for the e-mail correspondence on Stan Ulam. : (Andrew M. Kobos)

* * *

W maju 1999 przypada 15. rocznica smierci jednego z wielkich wspolczesnych geniuszow nauki, Stanislawa M. Ulama, urodzonego i wyksztalconego we Lwowie.

Podjalem probe napisania niecalkiem chronologicznego szkicu o Stanislawie Ulamie. Oparlem sie na jego autobiografii Adventures of a Mathematician (1976) i na materialach z dwoch numerow Los Alamos Science (2/1982 i 15/1987) oraz na dodatkowych informacjach od Profesora Gian-Carlo Rota z Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Jestem wdzieczny redakcji Los Alamos Science, w szczegolnosci Nikki Cooper, za informacje i pozwolenie na wykorzystanie materialow Los Alamos National Laboratory, tj. tekstow i fotografii z Los Alamos Science 15/1987 (specjalne wydanie, w calosci poswiecone Stanislawowi Ulamowi i jego naukowemu dziedzictwu), 3/1982 i 21/1993. Wdzieczny jestem rowniez Panu Profesorowi Gian-Carlo Rota z MIT, za korespondencje elektroniczna dotyczaca Stanislawa Ulama. (AMK)

…

…

Stan z ciezarna zona znalazl sie w tajnym laboratorium na plaskowyzu (mesa) Los Alamos, wsrod dotad najwiekszej w historii koncentracji uczonych. John von Neumann powiedzial mu od razu, ze chodzilo o problemy teoretyczne z masa krytyczna rozszczepialnego plutonu, ktory wowczas jeszcze nawet nie istnial. Po dwoch miesiacach, podnieceni Robert Oppenheimer i Victor Weisskopf przybiegli z probowka, na dnie ktorej bylo kilka tajemniczych kropli plutonu. Ulam zetknal sie po raz pierwszy z praktycznymi problemami fizyki, ktore laczyly sie wprost z danymi ekperymentalnymi. Pewnego razu zazartowal do fizyka Otto Frisch’a: „jestem czystym matematykiem, ktory upadl tak nisko, iz jego prace zawieraja prawdziwe liczby z dokladnoscia do kilku dziesietnych miejsc”. Ulam znalazl w sobie zdolnosc wyobrazania sobie nie tylko obrazu logicznego, ale i konkretnej sytuacji fizycznej oraz jej rozwiazania. Slynne stalo sie jego natychmiastowe, jak sie potem okazalo poprawne, oszacowanie stalej w pewnym wzorze jako okolo cztery.

Chociaz podstawowe efekty fizyczne byly zjawiskami kwantowymi, to rozwiazanie problemow techologicznych Bomby wymagalo zastosowania statystycznej mechaniki, tj. kinematyki, dynamiki i statystyki powielania neutronow oraz promieniowania. Byla to matematyka stosowana, nowe pole odkrywcze Ulama. Dyskutowal wiele z Enrico Fermi’m i Richardem Feynman’em o matematyce i fizyce, o mechanice statystycznej; Fermi znal doskonale podstawowa prace Ulama z Oxtoby’m z roku 1941. Ulam pracowal nad problemem powielania neutronow, w grupie Edwarda Tellera, zajmujacej sie juz (poczatkowo zreszta bardziej wskutek rozdzwiekow Teller-Bethe) nowa generacja „super” bomby, zwanej pozniej „bomba wodorowa”. Wniosl jednak swoj znaczny udzial w hydrodynamiczne obliczenia potrzebne juz wczesniej dla bomby atomowej.

Z poczatkiem roku 1944, w dlugiej dyskusji Ulama z von Neumannem wyplynela koniecznosc dokladniejszego, niz przyblizonym sposobem proponowanym przez von Neumanna, obliczenia hydrodynamicznego przebiegu implozji, niezbednej dla „zaplonu” bomby termonuklearnej. Trzeba bylo zastosowac „brutalna sile”, czyli masowe obliczenia numeryczne. Bylo to jednak niemozliwe przy uzyciu istniejacych mechanicznych urzadzen obliczeniowych. Niezbednosc tych wlasnie dokladnych obliczen zapoczatkowala rozwoj elektronicznych, wowczas jeszcze lampowych, komputerow. Powstaly z polaczenia osiagniec naukowych i technologicznych, w analogii z operacjami mozgu. W roku 1952 pojawil sie w Los Alamos MANIAC, drugi egzemplarz (po Princeton) pierwszego zmienno-programowalnego komputera. (Idee programowania wymyslil John von Neumann, wychodzac z logiki matematycznej).

W lipcu i sierpniu 1945, proba „Trinity” bomby atomowej, Hiroshima i kapitulacja Japonii zlowrozbnie (wg slow Ulama) rozpoczely „ere atomowa” i uczynily z bomby atomowej „wiadomosc publiczna”. Zaszczyty i rozglos spadly na… administacyjnych szefow Manhattan Project. Ulam przypomnial wowczas przedwojenna historyjke o pensjonariuszu w Berlinie, ktory zjadl swym wspolpensjonariuszom caly ugotowany asparagus, i ktoremu jeden z nich niesmialo zwrocil uwage: „Prosze wybaczyc, panie Goldberg, ale my rowniez lubimy asparagus.” Rozbawieni, planowali z von Neumann napisac dwudziestotomowy traktat pt. Asparagus poprzez wieki (Stan mial napisac ostatni tom). Nie zdazyli, John von Neumann zmarl w roku 1957.

Dla rozrywki Ulam grywal w pokera o male stawki; wsrod partnerow mial m. in. George’a Kistiakowsky’ego (chemika, specjaliste od eksplozji), Nicka Metropolis’a (z ktorym w roku 1946 rozwinal metode Monte Carlo) i Clyde’a Cowan’a – odkrywce neutrina w roku 1956 i laureata Nagrody Nobla w 1995 r.). Uwielbiali przy tym „slone” dowcipy. Od dziecinstwa Stan grywal bardzo dobrze w szachy, stworzyl znany klub szachowy w Los Alamos, w roku 1957 jeden z pierwszych eksperymentowal z gra w szachy na komputerach.

Cala rodzina Ulama w Polsce, wlaczajac siostre (poza dwoma kuzynami), zginela w Shoah, a matka Françoise Ulam w Auschwitz.

Swiat wyszedl z wojny inny. Dostrzezono kluczowa role nauki. Na uniwersytetach w Stanach Zjednoczonych powstawaly nowe centra fizyki. W jesieni 1945 Ulamowie przeniesli sie do Los Angeles, gdzie Ulam zostal profesorem na University of Southern California. W styczniu 1946 roku, gwaltowny wicher prawie zadlawil Stana na ulicy na pobliskiej wysepce Balboa. W nocy tego dnia, powalil go bol glowy i sztywnosc. Przyszedl mu mysl platonski opis smierci Sokratesa: „Kiedy sztywnosc dojdzie ci do glowy, umrzesz”. Nastepnej nocy prawie stracil mowe. Przewieziono go do szpitala, gdzie stwierdzono zapalenie mozgu. Po dwoch dniach umieral. Dr Rainey, neurochirurg, zdecydowal sie na natychmiastowa operacje, otwarcie czaszki. Obnizyl cisnienie mozgowe i spryskal rozowy juz mozg Ulama penicylina. Tym uratowal mu zycie.

….

więcej:http://www.zwoje-scrolls.com/zwoje16/text03.htm

In English – jak zwykle nieporównanie więcej i dokładniej niż w polskiej wiki

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (pronounced [’staɲiswaf 'mart͡ɕin 'ulam]; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a renowned Polish-American mathematician. He participated in America’s Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion. In pure and applied mathematics, he produced many results, proved many theorems, and proposed several conjectures.

Born into a wealthy Polish Jewish family, Ulam studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute, where he earned his D.Sc. in 1933 under the supervision of Kazimierz Kuratowski. In 1935, John von Neumann, whom Ulam had met in Warsaw, invited him to come to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, for a few months. From 1936 to 1939, he spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he worked to establish important results regarding ergodic theory. On 20 August 1939, he sailed for America for the last time with his 17 year old brother Adam Ulam. He became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1940, and a United States citizen in 1941.

In October 1943, he received an invitation from Hans Bethe to join the Manhattan Project at the secret Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. There, he worked on the hydrodynamic calculations to predict the behavior of the explosive lenses that were needed by an implosion-type weapon. He was assigned to Edward Teller’s group, where he worked on Teller’s „Super” bomb for Teller and Enrico Fermi. After the war he left to become an associate professor at the University of Southern California, but returned to Los Alamos in 1946 to work on thermonuclear weapons. With the aid of a cadre of female „computers”, including his wife Françoise Ulam, he found that Teller’s „Super” design was unworkable. In January 1951, Ulam and Teller came up with the Teller–Ulam design, which is the basis for all thermonuclear weapons.

Ulam considered the problem of nuclear propulsion of rockets, which was pursued by Project Rover, and proposed, as an alternative to Rover’s nuclear thermal rocket, to harness small nuclear explosions for propulsion, which became Project Orion. With Fermi and John Pasta, Ulam studied the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam problem, which became the inspiration for the vast field of Nonlinear Science. He is probably best known for realising that electronic computers made it practical to apply statistical methods to functions without known solutions, and as computers have developed, the Monte Carlo method has become a ubiquitous and standard approach to many problems.

Poland

Ulam was born in Lemberg, Galicia, on 13 April 1909. At this time, Galicia was in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, known to Poles as the Austrian partition. In 1918, it became part of the newly restored Poland, the Second Polish Republic, and the city took its Polish name again, Lwów.[1]

The Ulams were a wealthy Polish Jewish family of bankers, industrialists, and other professionals. Ulam’s immediate family was „well-to-do but hardly rich”.[2] His father, Józef Ulam, was born in Lwów and was a lawyer, and his mother, Anna (née Auerbach), was born in Stryj.[3] His uncle, Michał Ulam, was an architect, building contractor, and lumber industrialist.[4] From 1916 until 1918, Józef’s family lived temporarily in Vienna.[5] After they returned, Lwów became the epicenter of the Polish–Ukrainian War, during which the city experienced a Ukrainian siege.[1]

The Scottish Café’s building now houses the Universal Bank in Lviv, the present name of Lwów.

In 1919, Ulam entered Lwów Gymnasium Nr. VII, from which he graduated in 1927.[6] He then studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute. Under the supervision of Kazimierz Kuratowski, he received his Master of Arts degree in 1932, and became a Doctor of Science in 1933.[5][7] At the age of 18, in 1929, he published his first paper Concerning Function of Sets in the journal Fundamenta Mathematicae.[7] From 1931 until 1935, he traveled to and studied in Wilno (Vilnius), Vienna, Zurich, Paris, and Cambridge, England, where he met G. H. Hardy and Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar.[8]

Along with Stanisław Mazur, Mark Kac, Włodzimierz Stożek, Kuratowski, and others, Ulam was a member of the Lwów School of Mathematics. Its founders were Hugo Steinhaus and Stefan Banach, who were professors at the University of Lwów. Mathematicians of this „school” met for long hours at the Scottish Café, where the problems they discussed were collected in the Scottish Book, a thick notebook provided by Banach’s wife. Ulam was a major contributor to the book. Of the 193 problems recorded between 1935 and 1941, he contributed 40 problems as a single author, another 11 with Banach and Mazur, and an additional 15 with others. In 1957, he received from Steinhaus a copy of the book, which had survived the war, and translated it into English.[9] In 1981, Ulam’s friend R. Daniel Maudlin published an expanded and annotated version.[10]

Coming to America

In 1935, John von Neumann, whom Ulam had met in Warsaw, invited him to come to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, for a few months. In December of that year, Ulam sailed to America. At Princeton, he went to lectures and seminars, where he heard Oswald Veblen, James Alexander, and Albert Einstein. During a tea party at von Neumann’s house, he encountered G. D. Birkhoff, who suggested that he apply for a position with the Harvard Society of Fellows.[5] Following up on Birkhoff’s suggestion, Ulam spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts from 1936 to 1939, where he worked with John C. Oxtoby to establish results regarding ergodic theory. These appeared in Annals of Mathematics in 1941.[6][11]

On 20 August 1939, in Gdynia, Józef Ulam, along with his brother Szymon, put his two sons, Stanislaw and 17 year old Adam, on a ship headed for America.[5] Within two weeks, the Germans invaded Poland. Within two months, the Germans completed their occupation of western Poland, and the Soviets invaded and occupied eastern Poland. Within two years, Józef Ulam and the rest of his family were victims of the Holocaust, Steinhaus was in hiding, Kuratowski was lecturing at the underground university in Warsaw, Stożek and his two sons had been killed in the massacre of Lwów professors, and the last problem had been recorded in the Scottish Book. Banach survived the Nazi occupation by feeding lice at Rudolf Weigl’s typhus research institute. In 1963, Adam Ulam, who had become an eminent kremlinologist at Harvard,[12] received a letter from George Volsky,[13] who hid in Józef Ulam’s house after deserting from the Polish army. This reminiscence gave a chilling account of Lwów’s chaotic scenes in late 1939.[14] In later life Ulam described himself as „an agnostic. Sometimes I muse deeply on the forces that are for me invisible. When I am almost close to the idea of God, I feel immediately estranged by the horrors of this world, which he seems to tolerate”.[15]

In 1940, after being recommended by Birkhoff, Ulam became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Here, he became an United States citizen in 1941.[5] That year, he married Françoise Aron.[6] She had been a French exchange student at Mount Holyoke College, whom he met in Cambridge. They had one daughter, Claire. In Madison, Ulam met his friend and colleague C. J. Everett, with whom he would collaborate on a number of papers.[16]

Manhattan Project

Ulam’s ID badge photo from Los Alamos

In early 1943, Ulam asked von Neumann to find him a war job. In October, he received an invitation to join an unidentified project near Santa Fe, New Mexico.[5] The letter was signed by Hans Bethe, who had been appointed as leader of the theoretical division of Los Alamos National Laboratory by Robert Oppenheimer, its scientific director.[17] Knowing nothing of the area, he borrowed a New Mexico guide book. On the checkout card, he found the names of his Wisconsin colleagues, Joan Hinton, David Frisch, and Joseph McKibben, all of whom had mysteriously disappeared.[5] This was Ulam’s introduction to the Manhattan Project, which was America’s wartime effort to create the atomic bomb.[18]

Hydrodynamical calculations of implosion

A few weeks after Ulam reached Los Alamos in February 1944, the project experienced a crisis. In April, Emilio Segrè discovered that plutonium made in reactors would not work in a gun-type plutonium weapon like the „Thin Man”, which was being developed in parallel with a uranium weapon, the „Little Boy” that was dropped on Hiroshima. This problem threatened to waste an enormous investment in new reactors at the Hanford site and to make slow separation of uranium isotopes the only way to prepare fissile material suitable for use in bombs. To respond, Oppenheimer implemented, in August, a sweeping reorganization of the laboratory to focus on development of an implosion-type weapon and appointed George Kistiakowsky head of the implosion department. He was a professor at Harvard and an expert on precise use of explosives.[19]

The basic concept of implosion is to use chemical explosives to crush a chunk of fissile material into a critical mass, where neutron multiplication leads to a nuclear chain reaction, releasing a large amount of energy. Cylindrical implosive configurations had been studied by Seth Neddermeyer, but von Neumann, who had experience with shaped charges used in armor piercing ammunition, was a vocal advocate of spherical implosion driven by explosive lenses. He realized that the symmetry and speed with which implosion compressed the plutonium were critical issues,[19] and enlisted Ulam to help design lens configurations that would provide nearly spherical implosion. Within an implosion, because of enormous pressures and high temperatures, solid materials behave much like fluids. This meant that hydrodynamical calculations were needed to predict and minimize asymmetries that would spoil a nuclear detonation. Of these calculations, Ulam said:

The hydrodynamical problem was simply stated, but very difficult to calculate – not only in detail, but even in order of magnitude. In this discussion, I stressed pure pragmatism and the necessity to get a heuristic survey of the problem by simple-minded brute force, rather than by massive numerical work.[5]

Nevertheless, with the primitive facilities available at the time, Ulam and von Neumann did carry out numerical computations that led to a satisfactory design. This motivated their advocacy of a powerful computational capability at Los Alamos, which began during the war years,[20] continued through the cold war, and still exists.[21] Otto Frisch remembered Ulam as „a brilliant Polish topologist with a charming French wife. At once he told me that he was a pure mathematician who had sunk so low that his latest paper actually contained numbers with decimal points!”[22]

Statistics of branching and multiplicative processes

Even the inherent statistical fluctuations of neutron multiplication within a chain reaction have implications with regard to implosion speed and symmetry. In November 1944, David Hawkins[23] and Ulam addressed this problem in a report entitled „Theory of Multiplicative Processes”.[24] This report, which invokes probability-generating functions, is also an early entry in the extensive literature on statistics of branching and multiplicative processes. In 1948, its scope was extended by Ulam and Everett.[25]

Early in the Manhattan project, Enrico Fermi’s attention was focused on the use of reactors to produce plutonium. In September 1944, he arrived at Los Alamos, shortly after breathing life into the first Hanford reactor, which had been poisoned by a xenon isotope.[26] Soon after Fermi’s arrival, Teller’s „Super” bomb group, of which Ulam was a part, was transferred to a new division headed by Fermi.[27] Fermi and Ulam formed a relationship that became very fruitful after the war.[28]

Post war Los Alamos

In September 1945, Ulam left Los Alamos to become an associate professor at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. In January 1946, he suffered an acute attack of encephalitis, which put his life in danger, but which was alleviated by emergency brain surgery. During his recuperation, many friends visited, including Nicholas Metropolis from Los Alamos and the famous mathematician Paul Erdős,[29] who remarked: „Stan, you are just like before.”[5] This was encouraging, because Ulam was concerned about the state of his mental faculties, for he had lost the ability to speak during the crisis. Another friend, Gian-Carlo Rota, asserted in a 1987 article that the attack changed Ulam’s personality; afterwards, he turned from rigorous pure mathematics to more speculative conjectures concerning the application of mathematics to physics and biology.[30] This assertion was not accepted by Françoise Ulam.[31]

By late April 1946, Ulam had recovered enough to attend a secret conference at Los Alamos to discuss thermonuclear weapons. Those in attendance included Ulam, von Neumann, Metropolis, Teller, Stan Frankel, and others. Throughout his participation in the Manhattan Project, Teller’s efforts had been directed toward the development of a „super” weapon based on nuclear fusion, rather than toward development of a practical fission bomb. After extensive discussion, the participants reached a consensus that his ideas were worthy of further exploration. A few weeks later, Ulam received an offer of a position at Los Alamos from Metropolis and Robert D. Richtmyer, the new head of its theoretical division, at a higher salary, and the Ulams returned to Los Alamos.[32]

Monte Carlo method

Stan Ulam Holding the FERMIAC

Late in the war, under the sponsorship of von Neumann, Frankel and Metropolis began to carry out calculations on the first general-purpose electronic computer, the ENIAC. Shortly after returning to Los Alamos, Ulam participated in a review of results from these calculations.[33] Earlier, while playing solitaire during his recovery from surgery, Ulam had thought about playing hundreds of games to estimate statistically the probability of a successful outcome.[34] With ENIAC in mind, he realized that the availability of computers made such statistical methods very practical. John von Neumann immediately saw the significance of this insight. In March 1947 he proposed a statistical approach to the problem of neutron diffusion in fissionable material.[35] Because Ulam had often mentioned his uncle, Michał Ulam, „who just had to go to Monte Carlo” to gamble, Metropolis dubbed the statistical approach „The Monte Carlo method”.[33] Metropolis and Ulam published the first unclassified paper on the Monte Carlo method in 1949.[36]

Fermi, learning of Ulam’s breakthrough, devised an analog computer known as the Monte Carlo trolley, later dubbed the FERMIAC. The device performed a mechanical simulation of random diffusion of neutrons. As computers improved in speed and programmability, these methods became more useful. In particular, many Monte Carlo calculations carried out on modern massively parallel supercomputers are embarrassingly parallel applications, whose results can be very accurate.[21]

Teller–Ulam design

On 29 August 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first fission bomb, the RDS-1. Created under the supervision of Lavrentiy Beria, who sought to duplicate the American effort, this weapon was nearly identical to Fat Man, for its design was based on information provided by spies Klaus Fuchs, Theodore Hall, and David Greenglass. In response, on 31 January 1950, President Harry S. Truman announced a crash program to develop a fusion bomb.[37]

To advocate an aggressive development program, Ernest Lawrence and Luis Alvarez came to Los Alamos, where they conferred with Norris Bradbury, the laboratory director, and with George Gamow, Edward Teller, and Ulam. Soon, these three became members of a short-lived committee appointed by Bradbury to study the problem, with Teller as chairman.[5] At this time, research on the use of a fission weapon to create a fusion reaction had been ongoing since 1942, but the design was still essentially the one originally proposed by Teller. His concept was to put tritium and/or deuterium in close proximity to a fission bomb, with the hope that the heat and intense flux of neutrons released when the bomb exploded, would ignite a self-sustaining fusion reaction. Reactions of these isotopes of hydrogen are of interest because the energy per unit mass of fuel released by their fusion is much larger than that from fission of heavy nuclei.[38]

Ivy Mike, the first full test of the Teller–Ulam design (a staged fusion bomb), with a yield of 10.4 megatons on 1 November 1952

Because the results of calculations based on Teller’s concept were discouraging, many scientists believed it could not lead to a successful weapon, while others had moral and economic grounds for not proceeding. Consequently, several senior people of the Manhattan Project opposed development, including Bethe and Oppenheimer.[39] To clarify the situation, Ulam and von Neumann resolved to do new calculations to determine whether Teller’s approach was feasible. To carry out these studies, von Neumann decided to use electronic computers: ENIAC at Aberdeen, a new computer, MANIAC, at Princeton, and its twin, which was under construction at Los Alamos. Ulam enlisted Everett to follow a completely different approach, one guided by physical intuition. Françoise Ulam was one of a cadre of women „computers” who carried out laborious and extensive computations of thermonuclear scenarios on mechanical calculators, supplemented and confirmed by Everett’s slide rule. Ulam and Fermi collaborated on further analysis of these scenarios. The results showed that, in workable configurations, a thermonuclear reaction would not ignite, and if ignited, it would not be self-sustaining. Ulam had used his expertise in Combinatorics to analyze the chain reaction in deuterium, which was much more complicated than the ones in uranium and plutonium, and he concluded that no self-sustaining chain reaction would take place at the (low) densities that Teller was considering.[40] In late 1950, these conclusions were confirmed by von Neumann’s results.[31][41]

In January 1951, Ulam had another idea: to channel the mechanical shock of a nuclear explosion so as to compress the fusion fuel. On the recommendation of his wife,[31] Ulam discussed this idea with Bradbury and Mark before he told Teller about it.[42] Almost immediately, Teller saw its merit, but noted that soft X-rays from the fission bomb would compress the thermonuclear fuel more strongly than mechanical shock and suggested ways to enhance this effect. On 9 March 1951, Teller and Ulam submitted a joint report describing these innovations.[43] A few weeks later, Teller suggested placing a fissile rod or cylinder at the center of the fusion fuel. The detonation of this „spark plug”[44] would help to initiate and enhance the fusion reaction. The design based on these ideas, called staged radiation implosion, has become the standard way to build thermonuclear weapons. It is often described as the „Teller–Ulam design”.[45]

The Sausage device of Mike nuclear test (yield 10.4 Mt) on Enewetak Atoll. The test was part of the Operation Ivy. The Sausage was the first true H-Bomb ever tested, meaning the first thermonuclear device built upon the Teller-Ulam principles of staged radiation implosion.

In September 1951, after a series of differences with Bradbury and other scientists, Teller resigned from Los Alamos, and returned to the University of Chicago.[46] At about the same time, Ulam went on leave as a visiting professor at Harvard for a semester.[47] Although Teller and Ulam submitted a joint report on their design[43] and jointly applied for a patent on it,[18] they soon became involved in a dispute over who deserved credit.[42] After the war, Bethe returned to Cornell University, but he was deeply involved in the development of thermonuclear weapons as a consultant. In 1954, he wrote an article on the history of the H-bomb,[48] which presents his opinion that both men contributed very significantly to the breakthrough. This balanced view is shared by others who were involved, including Mark and Fermi, but Teller persistently attempted to downplay Ulam’s role.[49] „After the H-bomb was made,” Bethe recalled, „reporters started to call Teller the father of the H-bomb. For the sake of history, I think it is more precise to say that Ulam is the father, because he provided the seed, and Teller is the mother, because he remained with the child. As for me, I guess I am the midwife.”[50]

With the basic fusion reactions confirmed, and with a feasible design in hand, there was nothing to prevent Los Alamos from testing a thermonuclear device. On 1 November 1952, the first thermonuclear explosion occurred when Ivy Mike was detonated on Enewetak Atoll, within the US Pacific Proving Grounds. This device, which used liquid deuterium as its fusion fuel, was immense and utterly unusable as a weapon. Nevertheless, its success validated the Teller–Ulam design, and stimulated intensive development of practical weapons.[47]

Fermi–Pasta–Ulam problem

When Ulam returned to Los Alamos, his attention turned away from weapon design and toward the use of computers to investigate problems in physics and mathematics. With John Pasta, who helped Metropolis to bring MANIAC on line in March 1952, he explored these ideas in a report „Heuristic Studies in Problems of Mathematical Physics on High Speed Computing Machines”, which was submitted on 9 June 1953. It treated several problems that cannot be addressed within the framework of traditional analytic methods: billowing of fluids, rotational motion in gravitating systems, magnetic lines of force, and hydrodynamic instabilities.[51]

Soon, Pasta and Ulam became experienced with electronic computation on MANIAC, and by this time, Enrico Fermi had settled into a routine of spending academic years at the University of Chicago and summers at Los Alamos. During these summer visits, Pasta and Ulam joined him to study a variation of the classic problem of a string of masses held together by springs that exert forces linearly proportional to their displacement from equilibrium. Fermi proposed to add to this force a nonlinear component, which could be chosen to be proportional to either the square or cube of the displacement, or to a more complicated „broken linear” function. This addition is the key element of the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam problem, which is often designated by the abbreviation FPU.[52][53]

A classical spring system can be described in terms of vibrational modes, which are analogous to the harmonics that occur on a stretched violin string. If the system starts in a particular mode, vibrations in other modes do not develop. With the nonlinear component, Fermi expected energy in one mode to transfer gradually to other modes, and eventually, to be distributed equally among all modes. This is roughly what began to happen shortly after the system was initialized with all its energy in the lowest mode, but much later, essentially all the energy periodically reappeared in the lowest mode.[53] This behavior is very different from the expected equipartition of energy. It remained mysterious until 1965, when Kruskal and Zabusky showed that, after appropriate mathematical transformations, the system can be described by the Korteweg–de Vries equation, which is the prototype of nonlinear partial differential equations that have soliton solutions. This means that FPU behavior can be understood in terms of solitons.[54]

Nuclear propulsion

An artist’s conception of the NASA reference design for the Project Orion spacecraft powered by nuclear propulsion

Starting in 1955, Ulam and Frederick Reines considered nuclear propulsion of aircraft and rockets.[55] This is an attractive possibility, because the nuclear energy per unit mass of fuel is a million times greater than that available from chemicals. From 1955 to 1972, their ideas were pursued during Project Rover, which explored the use of nuclear reactors to power rockets.[56] In response to a question by Senator John O. Pastore at a congressional committee hearing on „Outer Space Propulsion by Nuclear Energy”, on January 22, 1958, Ulam replied that „the future as a whole of mankind is to some extent involved inexorably now with going outside the globe.”[57]

Ulam and C. J. Everett also proposed, in contrast to Rover’s continuous heating of rocket exhaust, to harness small nuclear explosions for propulsion.[58] Project Orion was a study of this idea. It began in 1958 and ended in 1965, after the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963 banned nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere and in space.[59] Work on this project was spearheaded by physicist Freeman Dyson, who commented on the decision to end Orion in his article, „Death of a Project”.[60]

Bradbury appointed Ulam and John H. Manley as research advisors to the laboratory director in 1957. These newly created positions were on the same administrative level as division leaders, and Ulam held his until he retired from Los Alamos. In this capacity, he was able to influence and guide programs in many divisions: theoretical, physics, chemistry, metallurgy, weapons, health, Rover, and others.[56]

In addition to these activities, Ulam continued to publish technical reports and research papers. One of these introduced the Fermi–Ulam model, an extension of Fermi’s theory of the acceleration of cosmic rays.[61] Another, with Paul Stein and Mary Tsingou, titled „Quadratic Transformations”, was an early investigation of chaos theory and is considered the first published use of the phrase „chaotic behavior”.[62][63]

Return to academia

When the positive integers are arrayed along the Ulam spiral, prime numbers, represented by dots, tend to collect along diagonal lines.

During his years at Los Alamos, Ulam was a visiting professor at Harvard from 1951 to 1952, MIT from 1956 to 1957, the University of California, San Diego, in 1963, and the University of Colorado at Boulder from 1961 to 1962 and 1965 to 1967. In 1967, the last of these positions became permanent, when Ulam was appointed as professor and Chairman of the Department of Mathematics at Boulder, Colorado. He kept a residence in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which made it convenient to spend summers at Los Alamos as a consultant.[64]

In Colorado, where he rejoined his friends Gamow, Richtmyer, and Hawkins, Ulam’s research interests turned toward biology. In 1968, recognizing this emphasis, the University of Colorado School of Medicine appointed Ulam as Professor of Biomathematics, and he held this position until his death. With his Los Alamos colleague Robert Schrandt he published a report, „Some Elementary Attempts at Numerical Modeling of Problems Concerning Rates of Evolutionary Processes”, which applied his earlier ideas on branching processes to biological inheritance.[65] Another, report, with William Beyer, Temple F. Smith, and M. L. Stein, titled „Metrics in Biology”, introduced new ideas about biometric distances.[66]

When he retired from Colorado in 1975, Ulam had begun to spend winter semesters at the University of Florida, where he was a graduate research professor. Except for sabbaticals at the University of California, Davis from 1982 to 1983, and at Rockefeller University from 1980 to 1984,[64] this pattern of spending summers in Colorado and Los Alamos and winters in Florida continued until Ulam died of an apparent heart attack in Santa Fe on 13 May 1984.[67] Paul Erdős noted that „he died suddenly of heart failure, without fear or pain, while he could still prove and conjecture.”[29] In 1987, Françoise Ulam deposited his papers with the American Philosophical Society Library in Philadelphia.[68] She continued to live in Santa Fe until she died on 30 April 2011, at the age of 93. Both Françoise and her husband are buried with her French family in Montmartre Cemetery in Paris.[69]

Impact and legacy

From the publication of his first paper as a student in 1929 until his death, Ulam was constantly writing on mathematics. The list of Ulam’s publications includes more than 150 papers.[6] Topics represented by a significant number of papers are: set theory (including measurable cardinals and abstract measures), topology, transformation theory, ergodic theory, group theory, projective algebra, number theory, combinatorics, and graph theory.[70] In March 2009, the Mathematical Reviews database contained 697 papers with the name „Ulam”.[71]

Notable results of this work are:

|

|

With his pivotal role in the development of thermonuclear weapons, Stanislaw Ulam changed the world. According to Françoise Ulam: „Stan would reassure me that, barring accidents, the H-bomb rendered nuclear war impossible.”[31] In 1980, Ulam and his wife appeared in the television documentary The Day After Trinity.[72]

An animation demonstrating the lucky number sieve. The numbers in red are lucky numbers

The Monte Carlo method has become a ubiquitous and standard approach to computation, and the method has been applied to a vast number of scientific problems.[73] In addition to problems in physics and mathematics, the method has been applied to finance, social science,[74] environmental risk assessment,[75] linguistics,[76] radiation therapy,[77] and sports.[78]

The Fermi–Pasta–Ulam problem is credited not only as „the birth of experimental mathematics”,[53] but also as inspiration for the vast field of Nonlinear Science. In his Lilienfeld Prize lecture, David K. Campbell noted this relationship and described how FPU gave rise to ideas in chaos, solitons, and dynamical systems.[79] In 1980, Donald Kerr, laboratory director at Los Alamos, with the strong support of Ulam and Mark Kac,[80] founded the Center for Nonlinear Studies (CNLS).[81] In 1985, CNLS initiated the Stanislaw M. Ulam Distinguished Scholar program, which provides an annual award that enables a noted scientist to spend a year carrying out research at Los Alamos.[82]

The fiftieth anniversary of the original FPU paper was the subject of the March 2005 issue of the journal Chaos,[83] and the topic of the 25th Annual International Conference of CNLS.[84] The University of Southern Mississippi and the University of Florida supported the Ulam Quarterly,[85] which was active from 1992 to 1996, and which was one of the first online mathematical journals.[86] Florida’s Department of Mathematics has sponsored, since 1998, the annual Ulam Colloquium Lecture,[87] and in March 2009, the Ulam Centennial Conference.[88]

Ulam’s work on non-Euclidean distance metrics in the context of molecular biology made a significant contribution to sequence analysis[89] and his contributions in theoretical biology are considered watersheds in the development of cellular automata theory, population biology, pattern recognition, and biometrics generally. Colleagues noted that some of his greatest contributions were in clearly identifying problems to be solved and general techniques for solving them.[90]

In 1987, Los Alamos issued a special issue of its Science publication, which summarized his accomplishments,[91] and which appeared, in 1989, as the book From Cardinals to Chaos. Similarly, in 1990, the University of California Press issued a compilation of mathematical reports by Ulam and his Los Alamos collaborators: Analogies Between Analogies.[92] During his career, Ulam was awarded honorary degrees by the Universities of New Mexico, Wisconsin, and Pittsburgh.[5]

Bibliography

- Kac, Mark; Ulam, Stanisław (1968). Mathematics and Logic: Retrospect and Prospects. New York: Praeger. ISBN 9780486670850. OCLC 24847821.

- Ulam, Stanisław (1974). Beyer, W. A.; Mycielski and, J.; Rota, G.-C., eds. Sets, Numbers, and Universes: selected works. Mathematicians of Our Time 9. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.-London. ISBN 978-0262021081. MR 0441664.

- Ulam, Stanisław (1960). A Collection of Mathematical Problems’. New York: Interscience Publishers. OCLC 526673.

- Ulam, Stanisław (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346. (autobiography).

- Ulam, Stanisław (1986). Science, Computers, and People: From the Tree of Mathematics. Boston: Birkhauser. ISBN 9783764332761. OCLC 11260216.

- Ulam, Stanisław; Ulam, Françoise (1990). Analogies Between Analogies: The Mathematical Reports of S.M. Ulam and his Los Alamos Collaborators. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520052901. OCLC 20318499.

References

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 9–15. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Ulam, Adam Bruno (2002). Understanding the Cold War: a historian’s personal reflections. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 9780765808851. OCLC 48122759. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Ulam, Molly (June 25, 2000). „Ulam Family of Lwow; Auerbachs of Vienna”. Genforum. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- „Genealogy of Michael Ulam”. GENi. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Ulam, Francoise (1987). „Vita”. Excerpts from Adventures of a Mathematician”. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Ciesielski, Kryzystof; Thermistocles Rassias (2009). „On Stan Ulam and His Mathematics”. Australian Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications. Retrieved 10 October 2011. „v 6, nr 1, pp 1-9, 2009”

- Andrzej M. Kobos (1999). „Mędrzec większy niż życie” [A Sage Greater Than Life]. Zwoje (in Polish) 3 (16). Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 56–60. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Ulam, Stanislaw (November 2002). „Preface to the „Scottish Book„„. Turnbull WWW Server. School of Mathematical and Computational Sciences University of St Andrews. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Maudlin, R. Daniel (1981). The Scottish Book. Birkhauser. p. 268. ISBN 9783764330453. OCLC 7553633. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- „Obituary for John C, Oxtoby”. The New York Times. 5 January 1991. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- „Obituary for Adam Ulam”. Harvard University Gazette. 6 April 2000. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- Volsky, George (23 December 1963). „Letter about Jozef Ulam”. Anxiously from Lwow. Adam Ulam. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- „Lwow lives on at Leopolis Press”. The Hook. 14 November 2002. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- Budrewicz/, Olgierd (1977). The melting-pot revisited: twenty well-known Americans of Polish background. Interpress. p. 36. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 125–130, 174. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 143–147. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- „Staff biography of Stanislaw Ulam”. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 130–137. ISBN 0-521-44132-3. OCLC 26764320.

- „Supercomputing”. History @ Los Alamos. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- „From Calculators to Computers”. History @ Los Alamos. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- Frisch, Otto (April 1974). „Somebody Turned the Sun on with a Switch”. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 30 (4): 17. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- Lehmann, Christopher (4 March 2002). „Obituary of David Hawkins”. The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Hawkins, D.; S. Ulam (14 November 1944). „Theory of Multiplicative Processes”. LANL report LA-171. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- Ulam, S.; C. J, Everett (7 June 1948). „Multiplicative Systems in Several Variables I, II, III”. LANL reports. University of California Press. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 304–307. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 152–153. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 162–157. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Erdos, Paul (1985). „Ulam, the man and the mathematician”. J. Graph Theory, v 9, p445-449. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- Rota, Gian-Carlo. „Stan Ulam: The Lost Cafe”. Los Alamos Science, No 15, 1987. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Ulam, Françoise (1991). Postscript to Adventures of a Mathematician. Berkeley, CA: University of California. ISBN 0-520-07154-9.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 184–187. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Metropolis, Nicholas (1987). „The Beginnings of the Monte Carlo Method”. Los Alamos Science, No 15. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Eckhardt, Roger (1987). „Stan Ulam, John von Neumann, and the Monte Carlo method”. Los Alamos Science, No 15. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Richtmyer, D.; J. Pasta and S. Ulam (9 April 1947). „Statistical Methods in Neutron Diffusion”. LANL report LAMS-551. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Metropolis, Nicholas; Stanislaw Ulam (1949). „The Monte Carlo method”. Journal of the American Statistical Association 44: 335–341. doi:10.2307/2280232. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, Volume II, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 406–409. ISBN 0-520-07187-5.

- Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 248. ISBN 0-684-80400-X.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 380–385. ISBN 0-520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478.

- Peter Galison (1996). „5: Computer Simulations and the Trading Zone”. In Peter Galison, David J. Stump. The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contexts, and Power. Stanford University Press. p. 135.

- Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 422–424. ISBN 0-684-80400-X.

- „Staff biography of J. Carson Mark”. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Teller, E.; S. Ulam (9 March 1951). „Heterocatalytic Detonations”. LANL report LAMS-1225. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- Teller, E. (4 April 1951), „A New Thermonuclear device”, Technical Report LAMS-1230, Los Alamos National Laboratory

- Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 455–464. ISBN 0-684-80400-X.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 554–556. ISBN 0-520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 220=224. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Bethe, Hans A. (Fall 1982). „Reprinting of 1954 article: Comments on the History of the H-Bomb”. Los Alamos Science, No 6. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- Uchii, Soshichi (22 July 2003). „Review of Edward Teller’s Memoirs”. PHS Newsletter 52. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Schweber, S. S. (2000). In the Shadow of the Bomb: Bethe, Oppenheimer, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-691-04989-2.

- Pasta, John; S. Ulam (9 March 1953). „Heuristic studies in problems of mathematical physics”. LANL report LA-1557. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- Fermi, E.; J. Pasta and S. Ulam (May 1955). „Studies of Nonlinear Problems I”. LANL report LA-1940. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- Porter, Mason A.; Norman J, Zabusky, Bambi Hu and David K. Campbell (May–Jun 2009). „Fermi, Pasta, Ulam and the Birth of Experimental Mathematics”. American Scientist 97 (3): 214–221. doi:10.1511/2009.78.214. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- „Focus: Landmarks—Computer Simulations Led to Discovery of Solitons”. Physics 6 (15). February 8, 2013. doi:10.1103/Physics.6.15.

- Longmier, C.; F. Reines and S. Ulam (August 1955). „Some Schemes for Nuclear Propulsion”. LANL report LAMS-2186. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- Ulam, S. M (1983). Adventures of a Mathematician. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 249–250. ISBN 9780684143910. OCLC 1528346.

- Schreiber, R. E.; Ulam, Stanislaw M.; Bradbury, Norris (1958). „US Congress, Joint Committee on Atomic Energy: hearing on 22 January 1958”. Outer Space Propulsion by Nuclear Energy. US Government Printing Office. p. 47. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- Everett, C. J.; S. M. Ulam (August 1955). „On a Method of Propulsion of Projectiles by Means of External Nuclear Explosions”. LANL report LAMS-1955. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- „History of Project Orion”. The Story of Orion. OrionDrive.com. 2008–2009. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Dyson, Freeman (9 July 1965). „Death of a Project”. Science 149: 141–144. doi:10.1126/science.149.3680.141.

- Ulam, S. M. (1961), „On Some Statistical Properties of Dynamical Systems”, Proceedings of the 4th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley CA, v 3, p 315: University of California Press

- Abraham, Ralph (9 July 2011). „Image Entropy for Discrete Dynamical Systems”. University of California, Santa Cruz. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Stein, P. R.; Stanislaw M. Ulam (March 1959). „Quadratic Transformations. Part I”. LANL report LA-2305. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- „Stanislaw Ulam”. American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Schrandt, Robert G.; Stanislaw M. Ulam (December 1970). „Some Elementary Attempts at Numerical Modeling of Problems Concerning Rates of Evolutaionary Processes”. LANL report LA-4246. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- Beyer, William A.; Temple F. Smith, M. L. Stein, and Stanislaw M. Ulam (August 1972). „Metrics in Biology, an Introduction”. LANL report LA-4973. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- Sullivan, Walter (15 May 1984). „Stanislaw Ulam, Theorist on Hydrogen Bomb”. New York Times. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- „Stanislaw M. Ulam Papers”. American Philosophical Society. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- „Françoise Ulam Obituary”. Santa Fe, New Mexican. 30 April 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- „Publications of Stanislaw M. Ulam”. Los Alamos Science, No 15, 1987. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- „Search for „Ulam” on AMS website”. American Mathematical Society. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- The Day After Trinity at the Internet Movie Database

- Eckhardt, Roger (Special Issue, 1987). „Stan Ulam, John von Neumann, and the Monte Carlo Method”. Los Alamos Science. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Casey, Thomas M. (June 2011). „Course description:Monte Carlo Methods for Social Scientists”. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. University of Michigan. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Poulter, Susan R. (Winter 1998). „Monte Carlo Simulation in Environmental Risk Assessment”. Risk:Health, Safety, & Environment. University of New Hampshire. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- Klein, Sheldon (23 May 1966). „Historical Change in Language Using Monte CarloTechniques”. Mechanical Translation and Computational Linguistics 9 (3 and 4): 67–81. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Earl, M. A.; L. M. Ma (12 March 2002). „Dose Enhancement of electron beams subject to external magnetic fields: A Monte Carlo Study”. Medical Physics 29: 484–492. doi:10.1118/1.1461374. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Ludwig, John (November 2011). „A Monte Carlo Simulation of the Big10 race”. ludwig.com. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Campbell, Donald H. (17 March 2010). „The Birth of Nonlinear Science”. Americal Physical Society. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- „CNLS: apprecion of Martin Kruskal and Alwyn Scott”. Los Alamos National Laboratory. 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- „History of the Center for Nonlinear Studies”. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- „Ulam Scholars at CNLS”. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- „Focus-Issue: The Fermi-Pasta-Ulam Problem-The-First-50-Years”. Chaos 15 (1). March 2005. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- „50 Years of the Fermi-Pasta-Ulam Problem: Legacy, Impact, and Beyond”. CLNS 25th International Conference. Los Alamos National Laboratory. May 16–20, 2005. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- „Home Page for Ulam Quarterly”. University of Florida. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- Dix, Julio G. (June 25–27, 2004), „Some Aspects of Running a Free Electronic Journal”, in Becker, Hans, New Developments in Electronic Publishing, Stockholm: European Congress of Mathematicians; ECM4 Satellite Conference, pp. 41–43, retrieved 5 January 2013, „ISBN 3-84 8127”

- „List of Ulam Colloquium Speakers”. University of Florida, Dept. of Mathematics. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- „Ulam Centennial Conference”. University of Florida. March 10–11, 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- Goad, Walter B (1987). „Sequence Analysis: Contributions of Ulam to Molecular Genetics”. Los Alamos Science. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Beyer, William A.; Peter H. Sellers, and Michael S. Waterman (1985). „Stanislaw M. Ulam’s Contributions to Theoretical Biology”. Letters in Mathematical Physics 10: 231–242. doi:10.1007/bf00398163. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- Cooper, Necia Grant. „Stanislaw Ulam 1909–1984”. Los Alamos Science, No 15, 1987. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Ulam, S. M. (1990). A. R. Bednarek and Françoise Ulam, ed. Analogies Between Analogies. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05290-0. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stanislaw Ulam. |

„Publications of Stanislaw M. Ulam”. Los Alamos Science. Special Issue 1987. ISSN 0273-7116.