Old European Culture: Blagotin

Puszczam ten tekst bez komentarza, wnioski wyciągnijcie sami.

©Tłumaczenie: Czesław Białczyński

In the 6th millennium bc, in Serbia we find Vinča culture. I believe that everyone reading this post have heard of the Vinča culture, the culture that invented metallurgy, alphabet. Slightly earlier, at the end of the 7th millennium bc we find on the same territory of Central Serbia, the Blagotin culture. I can bet that most people reading this post have never heard of the Blagotin culture.

Let me tell you a story about Blagotin culture.

W VI tysiącleciu pne w Serbii znajdujemy kulturę Vinča. Wierzę, że wszyscy czytający ten post słyszeli o kulturze Vinča, kulturze, która wynalazła metalurgię, alfabet. Nieco wcześniej, pod koniec 7. tysiąclecia pne znajdujemy na tym samym terytorium środkowej Serbii, kulturę Blagotin. Mogę się założyć, że większość osób czytających ten post nigdy nie słyszała o kulturze Blagotin.

Pozwól, że opowiem Ci historię o kulturze Blagotin.

Archaeological locality Blagotin got its name after the hill called „Mali Blagotin” under which it is located. Mali Blagotin is located in the heart of Serbia, in an area known as Šumadija. The region is characterized by a southern variant of the Central European temperate climatic regime. The site is located on the northern outskirts of the village of Poljna, 12 km north of the slightly larger village of Velika Drenova, and about 50 km northeast of the town of Trstenik (in the county or opština of Trstenik). It is on a gently sloping terrace, above an incised stream valley at the base of a mountain. The surface of the site was entirely cultivated during the period of field research. Blagotin is a multi-period and strati-graphically complex site. It was initially inhabited during the Early Neolithic (Starčevo culture, ca. 6100–5100 B.C.). Recent radiocarbon dates place it among the earliest sites in the Starčevo culture – ca. 6100 B.C.

Miejscowość archeologiczna Blagotin ma swoją nazwę od wzgórza zwanego „Mali Blagotin”, pod którym się znajduje. Mali Blagotin znajduje się w sercu Serbii, w okolicy znanej jako Szumadija. Region ten charakteryzuje południowy wariant klimatu umiarkowanego środkowoeuropejskiego. Obszar położony jest na północnych obrzeżach miejscowości Poljna, 12 km na północ od nieco większej wioski Velika Drenova i około 50 km na północny wschód od miasta Trstenik (w powiecie lub w obszczinie [okręgu/obwodzie CB] Trstenik). Znajduje się na łagodnie opadającym tarasie, nad wyciętą doliną potoku u podnóża góry. Powierzchnia terenu była w całości badana podczas badań terenowych. Blagotin to założenie składajace się z wielu okresów i kompleksów stratygraficznych. Pierwotnie był zamieszkiwany w okresie wczesnego neolitu (kultura Starčevo, ok. 6100-5100 pne). Niedawne datowania radiowęglowe stawiają ją w najwcześniejszych okresach kultury Starčevo – ca. 6100 B.C.

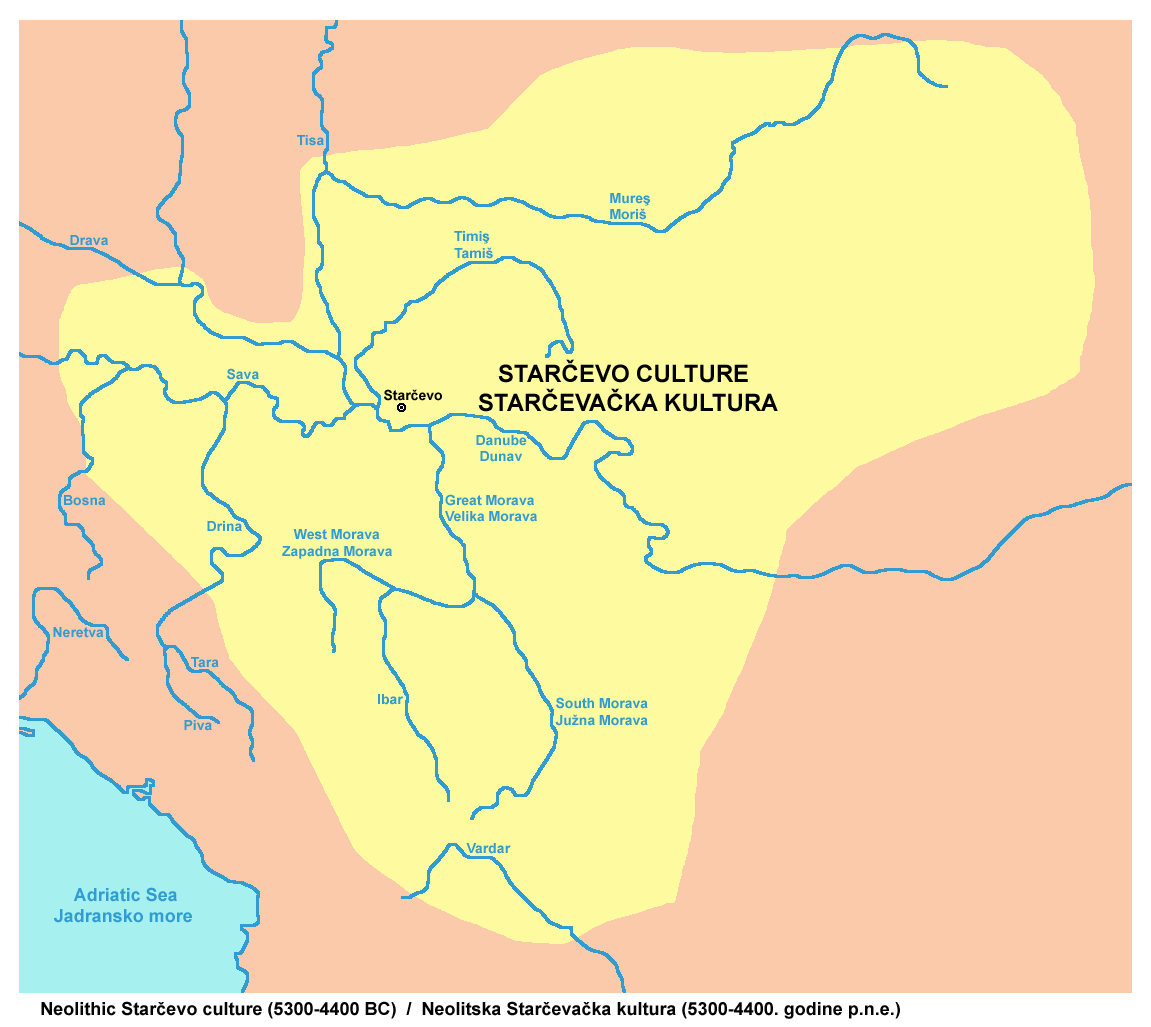

The Starčevo culture, sometimes included within a larger grouping known as the Starčevo–Kőrös–Criş culture, is an archaeological culture of Southeastern Europe.The Starčevo culture covered sizable area that included most of present-day Serbia and Montenegro, as well as parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, and the Republic of Macedonia.

Kultura Starčevo, którą czasami ujmuje się w większej grupie zwanej kulturą Starčevo-Kőrös-Criş, jest kulturą archeologiczną Europy Południowo-Wschodniej. Kultura Starčevo obejmowała większa część obszaru dzisiejszej Serbii i Czarnogóry, a także część Bośni i Hercegowiny, Chorwacji, Węgier i Republiki Macedonii.

Blagotin site was then reoccupied during the Eneolithic (Baden-Kostolac culture, ca. 3300–2500 B.C.), and then occupied again during the Early Iron Age (Halstatt culture, ca. 1000–700 B.C.). It was not occupied again until modern times. Here is where the Blagotin site is on the map of the Balkans.

The reason why people kept coming back to Blagotin and settling there for thousands of years is that Blagotin area as well as central Serbia as a whole is an ideal place for subsistence farming combined with hunting and gathering. Central Serbia consists of a series of small to medium alluvial river valley planes formed by river Morava and its tributaries, surrounded by rolling hills and medium size mountains. These alluvial valley plains were created by the deposition of sediment over a long period of time by one or more rivers and streams coming from highland regions, from which alluvial soil forms. These rivers still flow through these valleys and form floodplains. The floodplains are the smaller area over which the rivers flood at a particular period of time, like in the spring during the snow melt, whereas the alluvial plain is the larger area representing the region over which the floodplains have shifted over geological time. Alluvial plains and flood plains are very very fertile and very easy to work with primitive agricultural tools such as hand plows and adzes made out of antler like this one:

Powodem, dla którego ludzie powracali do Blagotinu i osiedlali się tam od tysięcy lat, jest to, że obszar Blagotinu, a także centralna Serbia jako całość, jest idealnym miejscem do uprawy na własne potrzeby połączone z polowaniem i zbieractwem. Centralna Serbia składa się z serii małych i średnich aluwialnych dolin rzecznych utworzonych przez rzekę Morawę i jej dopływy, otoczoną pagórkami i średniej wielkości górami. Te równiny dolin aluwialnych zostały utworzone przez osadzanie się osadów przez długi czas przez jedną lub więcej rzek i strumieni pochodzących z regionów górskich, z których tworzy się gleba aluwialna. Te rzeki nadal przepływają przez te doliny i tworzą terasy zalewowe. Teren zalewowy to mniejszy obszar, który rzeki zalewają się w określonym czasie, jak na wiosnę podczas topnienia śniegu, podczas gdy równina aluwialna to większy obszar reprezentujący region, nad którym terasy zalewowe przesunęły się w czasie geologicznym. Równiny łęgowe i równiny zalewowe są bardzo żyzne i bardzo łatwe w uprawie prymitywnymi narzędziami rolniczymi, takim jak ręczne pługi i radła wykonane z poroża, takie jak to:

Or wood and stone ones like these ones:

Albo z drzewa i kamienia jak te:

It is in the alluvial and flood plains that grain agriculture developed and flourished in the early Neolithic times. This is the list of main alluvial and flood plains in Asia and North Africa.

To właśnie na równinach aluwialnych i zalewowych nastąpił rozwój rolnictwa zbożowego we wczesnych czasach neolitu. Oto lista głównych równin aluwialnych i zalewowych w Azji i Afryce Północnej.

Po valley plain

Punjab alluvial plain

Indo-Gangetic plain

Tigris–Euphrates plain

Nile valley

Yangtze valley

You can see that these alluvial flood plains are the exact places where the early farmers settled and formed the first agricultural civilizations. The soil is sandy and therefore easy to work, it is rich and gives high yields, and it is regularly enriched with new flood deposits preventing soil depletion, which was the main problem for early farmers.

In Central Europe we find the Lower Danube-Sava-Morava-Tisa Central European alluvial flood plains. And this is exactly the place where we find the most advanced Early European Neolithic agricultural civilizations.

This is the map showing Blagotin hill, an Island in the middle of an area of rolling hills and small river valleys.

Widać, że te aluwialne równiny zalewowe są dokładnymi miejscami, w których pierwsi rolnicy osiedlili się i utworzyli pierwsze rolnicze cywilizacje. Gleba jest piaszczysta i dlatego jest łatwa w obróbce, jest bogata i daje wysokie plony, i jest regularnie wzbogacana o nowe osady powodziowe co zapobiega zubożeniu gleby, co z kolei było głównym problemem dla wczesnych rolników.

W Europie Środkowej znajdujemy aluwialne równiny zalewowe Dolny Dunaj-Sava-Morava-Tisa środkowoeuropejskie. I to jest właśnie miejsce, w którym znajdujemy najbardziej zaawansowane wczesnoeuropejskie neolityczne cywilizacje rolnicze.

Jest to mapa przedstawiająca wzgórze Blagotin, wyspę położoną pośrodku obszaru wzgórz i niewielkich dolin rzecznych.

16 kilometers to the south from the Blagotin hill is Zapadna Morava river valley. This is what this river valley looked like during last year’s floods.

16 kilometrów na południe od wzgórza Blagotin znajduje się dolina rzeki Zachodnia Morava. Tak wyglądała ta dolina rzeki podczas ubiegłorocznych powodzi.

The valley was flooded after a sudden snow melt combined with heavy rain and saturated ground from previous rains. These types of floods are today very rare because the river now has flood defenses built along its banks. In the distant past this kind of flooding of the river valley was much more frequent and kept the valley floor extremely fertile.

This is what this river valley looks like on a nice dry sunny day.

Dolina została zalana po nagłym roztopie śniegu w połączeniu z ulewnym deszczem i nasyceniem gruntu z poprzednich deszczy. Tego typu powodzie są dziś bardzo rzadkie, ponieważ rzeka ma teraz osłony przeciwpowodziowe zbudowane wzdłuż jej brzegów. W odległej przeszłości ten rodzaj zalewu doliny rzeki był znacznie częstszy i utrzymywał wyjątkowo żyzną glebę.

Tak wygląda ta dolina rzeki w piękny, suchy, słoneczny dzień.

If you look at the above picture of the river valley, you can see that the bottom of the valley is completely flat, a sign of an alluvial deposits, the prime agricultural land. From the Zapadna Morava river, the therein towards Blagotin hill is a slightly raised plateau consisting of rolling hills and small flat old alluvial river valleys. It is called Poljna plain. Poljna literally means a plain.

This is what I am talking about. This is Poljna plain which lies between Blagotin hill and Zapadna Morava river.

Jeśli spojrzeć na powyższy obraz doliny rzeki, widać, że dno doliny jest całkowicie płaskie, co jest oznaką złóż aluwialnych, głównej ziemi rolnej. Z rzeki Zapadna/Zachodnia Morava, w kierunku wzgórza Blagotin znajduje się lekko podniesiony płaskowyż składający się z pagórków i małych, płaskich, dawnych, aluwialnych dolin rzecznych. To się nazywa równina Poljna. Poljna oznacza dosłownie równinę.

O tym właśnie mówię. Jest to równina Poljna, która leży pomiędzy wzgórzem Blagotin i rzeką Zapadną/Zachodnią Morawą.

This is the exact location of Blagotin site just beneath the Blagotin hill at the edge of Poljna plain:

Dokładna lokalizacja miejsca Blagotin tuż pod wzgórzem Blagotin na skraju równiny Poljna:

The hills surrounding these river valleys used to be covered with mixed oak forests. The name of the region „Šumadija” means the land of forests. These forests were full of oaks, hazels, beaches and therefore full of edible nuts, acorns and beach nuts as well as mushrooms and berries and other wild fruit like wild apples, pears and cherries. All these wild foods were found in deposits belonging to the early neolithic cultures in the Balkans. The river itself is full of fish even today and it must have been teaming with fish in Neolithic times. The whole area is also full of wild birds and animals even today, and in the Neolithic times it must have been an ideal hunting ground.

At the end of the 7th millennium, the Neolithic farmers arriving from the Levant crossed the mountains dividing the Mediterranean climatic zone and the Semi Continental Balkan climatic zone and found themselves in these river valleys. There they had to learn how to adapt their agricultural techniques to this new climate. I would say that that was a quite a big challenge which took a good while. The neolithic farmers which arrived from Levant stayed in Serbia for almost 1000 years before moving further north. But once they started this move north it was very quick and only 500 years later we find them on the shores of Holland. During the time when agriculture was still developing and adapting to the European climate, and when people still heavily depended on hunting and gathering, the area around Blagotin, with its abundance of wild food would have been and ideal place to settle.

How good Blagotin is for living is actually reflected in its name. The Serbian word „blag” means gentle, sweet, but also domesticated, cattle and treasure. The ending „tin, ten, tan, din, den, dan” are quite common endings found in village and town names in Serbia and correspond to the Irish „dun” meaning enclosure, village, town, place….The name Blagotin literally means gentle, cultivated, rich place good for living…

So the Neolithic farmers arrived to Blagotin and built a settlement. But not just any settlement. The settlement covers the area between one and two hectares which would classify it as a medium size settlement. But it is the structure of the settlement, its layout, which sets it apart from all the other settlements of its time. Blagotin settlement type was completely different from both Levantine and Southern Balkan and Central and Northern European settlement types.

Wzgórza otaczające te doliny rzeczne były kiedyś pokryte mieszanym lasem dębowym. Nazwa regionu „Szumadija” oznacza krainę lasów. Lasy te były pełne dębów, leszczyn, buków i dlatego pełne były jadalnych orzechów, żołędzi i orzechów bukowych, a także grzybów i jagód oraz innych dzikich owoców, takich jak dzikie jabłka, gruszki i czereśnie. Wszystkie te dzikie pokarmy znaleziono w osadach należących do wczesnych kultur neolitycznych na Bałkanach. Sama rzeka jest dziś pełna ryb i musiała być jeszcze bardziej sprzyjać rybołówstwu w czasach neolitu. Cały teren jest pełen dzikiego ptactwa i zwierząt nawet dzisiaj, a w czasach neolitu musiał być idealnym obszarem łowieckim.

Pod koniec siódmego tysiąclecia w neolicie rolnicy przybyli z Lewantu przekroczyli góry dzielące śródziemnomorską strefę klimatyczną i północno-zachodnią strefę klimatyczną Bałkanów i znaleźli się w dolinach rzek. Tam musieli nauczyć się dostosowywać swoje techniki rolnicze do tego nowego klimatu. Powiedziałbym, że było to dość duże wyzwanie, które trwało bardzo długo. Neolityczni rolnicy, którzy przybyli z Lewantu, przebywali w Serbii przez prawie 1000 lat, zanim przenieśli się dalej na północ. Ale kiedy zaczęli ten ruch na północ, działo się to bardzo szybko i zaledwie 500 lat później znajdujemy ich na wybrzeżu Holandii. W czasach, gdy rolnictwo wciąż się rozwijało i dostosowywało do europejskiego klimatu, a ludzie nadal w dużym stopniu polegali na polowaniu i zbieractwie, obszary wokół Blagotin, z obfitością dzikiej żywności byłby idealnym miejscem do osiedlenia się.

Jak dobry jest Blagotin do życia, odzwierciedla się w jego nazwie. Serbskie słowo „blag” oznacza łagodne, słodkie, ale także udomowione, bydło i skarb. Zakończenie „tin, ten, tan, din, den, dan” są dość powszechnymi zakończeniami znalezionymi we wsiach i miastach w Serbii i odpowiadają irlandzkiemu „dun” oznaczającemu zamknięcie, wioskę, miasto, miejsce …. Nazwa Blagotin dosłownie oznacza łagodny, uprawiany, bogate miejsce dobre do życia … (polskie tyn, tyniec – miejsce ogrodzone, otoczone murem, obwałowane, obronne CB)

Tak więc w neolicie rolnicy przybyli do Blagotin i zbudowali osadę. Ale nie jest to byle jaka osada. Osada ta obejmuje obszar od jednego do dwóch hektarów, co klasyfikuje ją jako osadę średniej wielkości. Ale to struktura osady, jej układ, odróżnia ją od wszystkich innych osad tamtych czasów. Typ osadnictwa Blagotin był całkowicie odmienny od typów osadniczych Lewantynu i Południowycho Bałkanów oraz Europy Środkowej i Północnej.

In the work on spatial organization of the site entitled: „The spatial organization of Early Neolithic settlements in temperate southeastern Europe: a view from Blagotin, Serbia.” published by Haskel J. Greenfeld and Tina Jongsma, from the University of Manitoba point to a very important difference between the spatial organisation of Blagotin settlement compared to all the other contemporary early neolithic settlements:

In Levant and the southern or Mediterranean half of the Balkan Peninsula (Greece, Macedonia, and southern Bulgaria), most early neolithic settlements are represented by tell-like deposits, with rectilinear above-ground and free-standing architecture.

Very different kinds of archaeological deposits are found in the major Early Neolithic archaeological cultures of central Europe. Most sites are very shallow, with little if any vertical superposition of deposits. They are largely characterized by laterally displaced deposits. The architectural forms in LBK sites tend to be very rectangular surface structures. Characteristically, they are extremely long and easily identifiable by the distribution of post molds in the soil. In LBK sites where settlement has been short term and the distribution of features is visible, long houses are placed parallel to each other, although it is difficult to perceive the presence of any clear rows.

In the northern or temperate half of the Balkan peninsula and extending across the rest of southeastern Europe, early neolithic tell-like settlements and long house settlements are almost non-existent. Instead, most sites appear to be composed of laterally displaced horizontal deposits associated with pit house deposits. The early neolithic Starčevo culture site of Blagotin is one such pit house site. Two types of pit houses are distinguishable.

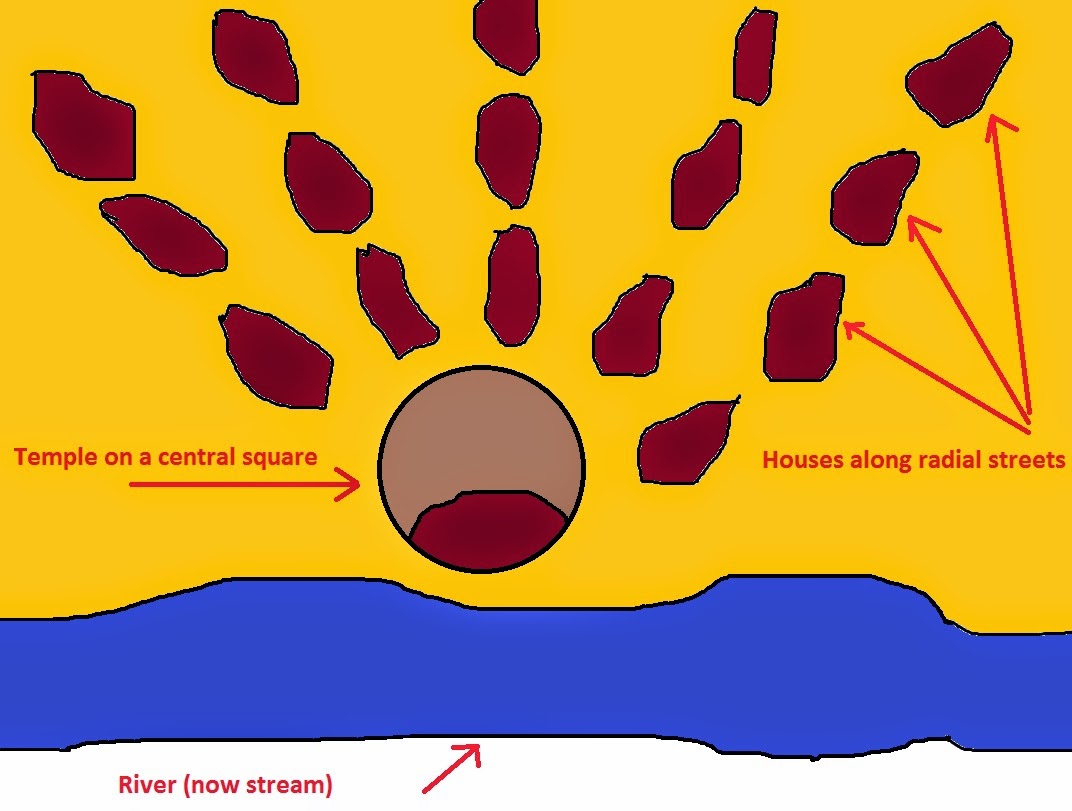

A smaller and shallower set of pit houses, 3 m wide and 6 m long, is distributed in a circle around a large open space. These smaller houses are arranged along radial streets which all lead to the central square. According to the professor Stanković there were 100 of these houses which means that the estimated population of Blagotin was around 500 people.

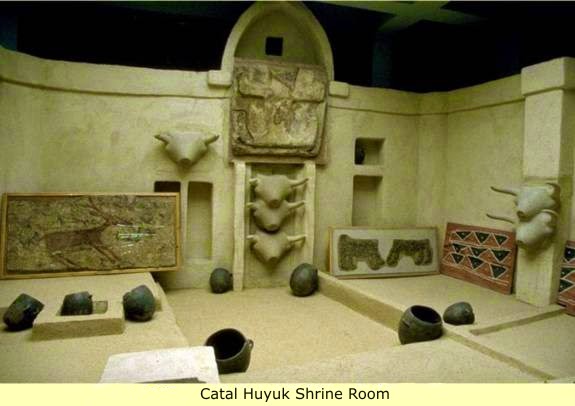

The second larger and deeper pit, approximately 10 m wide and 8 m long, is found at the center of the large open space, central square. The central house is clearly very different from those surrounding it and based on its design and the deposits found in it, it is undoubtedly a sacred place, a temple. This make Blagotin temple the oldest purposely built temple in Europe and the Second (or third) oldest temple in the world, after Gobelki Tepe (and possibly some Çatalhöyük dwellings if they can be classified as temples).

The oldest known temple in the world is that at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey which is 11,500 years old and is decorated with reliefs and pictograms of various plants and animals thought to represent the gods of that place. The temple is an extraordinary building of the Neolithic era with T-shaped pillars and engravings which have yet to be completely understood. The design of the temple, however, with a large room toward the front (possibly for public functions) is recognized in later temples from other cultures.

Bardzo różne rodzaje depozytów znajdują się w wielkich kulturach archeologicznych wczesnego neolitu w środkowej Europie. Większość miejsc jest bardzo płytka, z niewielką, jeśli w ogóle, pionową superpozycją depozytów. Charakteryzują się one w większości zjawiskami przesuniętymi w bok. Formy architektoniczne (domostwa) w miejscach LBK mają tendencję do tworzenia prostokątnych struktur czytelnych na powierzchni. Są one charakterystyczne, wyjątkowo długie i łatwe do zidentyfikowania dzięki rozmieszczeniu słupów w glebie. W lokalizacjach LBK, gdzie osiedlenie było krótkotrwałe, W lokalizacjach LBK, gdzie rozliczenie było krótkotrwałe, a rozkład cech jest widoczny, długie domy są umieszczone równolegle do siebie, chociaż trudno jest dostrzec obecność jakichkolwiek wyraźnych rzędów.

W północnej lub środkowej połowie Półwyspu Bałkańskiego i rozciągającej się na pozostałą część południowo-wschodniej Europy, wczesne, neolityczne osiedla i wzdłużne osiedla domów prawie nie istnieją. Zamiast tego, większość miejsc wydaje się składać z poprzecznie przemieszczonych poziomych depozytów związanych z osadami domów wgłębionych. Wczesna neolityczna osada kultury w Starčevo w Blagotin jest jednym z takich miejsc. Można wyróżnić w niej dwa typy domów wgłębionych.

Mniejszy i płytszy zestaw domów mieszkalnych, o szerokości 3 m i długości 6 m, jest rozmieszczony w okręgu wokół dużej otwartej przestrzeni. Te mniejsze domy rozmieszczone są wzdłuż promienistych ulic, które prowadzą do głównego placu. Według profesora Stankovicia było tych domów 100, co oznacza, że szacowana populacja Blagotin wynosiła około 500 osób.

Drugi większy i głębszy model to dół, o szerokości około 10 m i długości 8 m, znajduje się pośrodku dużej otwartej przestrzeni, centralnego placu. Dom centralny wyraźnie różni się od otaczających go domów, dotyczy to zarówno jego konstrukcji jak i znalezionych w nim depozytów, jest niewątpliwie świętym miejscem, świątynią. To sprawia, że świątynia Blagotin jest najstarszą celowo zbudowaną świątynią w Europie i drugą (lub trzecią) najstarszą świątynią na świecie, po Gobelki Tepe (i prawdopodobnie niektórych obiektach w Çatalhöyük, jeśli można je zaklasyfikować jako świątynie).

Najstarszą znaną świątynią na świecie jest Göbekli Tepe w południowo-wschodniej Turcji, która ma 11 500 lat i jest ozdobiona płaskorzeźbami i piktogramami różnych roślin i zwierząt uważanych za reprezentujących bogów tego miejsca. Świątynia jest niezwykłym budynkiem z epoki neolitu z filarami w kształcie litery T i rycinami, które nie zostały jeszcze całkowicie zrozumiane. Projekt świątyni, jednak z dużym pokojem w kierunku przodu (prawdopodobnie w przypadku funkcji publicznych) jest rozpoznawany w późniejszych świątyniach z innych kultur.

Çatalhöyük, the largest and best-preserved Neolithic site found to date, was composed entirely of domestic buildings, with no obvious public buildings. However some of the larger ones have rather ornate murals, the purpose of some rooms remain unclear. Vivid murals and figurines are found throughout the settlement, on interior and exterior walls. Distinctive clay figurines of women, notably the Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük have been found in the upper levels of the site. Although no identifiable temples have been found, the graves, murals, and figurines suggest that the people of Çatalhöyük had a religion rich in symbols. Rooms with concentrations of these items may have been shrines or public meeting areas.

Çatalhöyük, największa i najlepiej zachowana budowla neolityczna, została zbudowana w całości z budynków mieszkalnych, bez „oczywistych” budynków publicznych. Jednak niektóre z większych mają ozdobne freski, cel niektórych pomieszczeń pozostaje niejasny. Widoczne freski i figurki znajdują się w całej osadzie, na ścianach wewnętrznych i zewnętrznych. Charakterystyczne gliniane figurki kobiet, w szczególności Siedząca Kobieta z Çatalhöyük, zostały znalezione na wyższych poziomach terenu. Chociaż nie znaleziono żadnych możliwych do zidentyfikowania świątyń, groby, freski i figurki sugerują, że ludzie z Çatalhöyük mieli religię bogatą w symbole. Pomieszczenia o dużej koncentracji tych przedmiotów mogły stanowić sanktuaria lub miejsca spotkań publicznych.

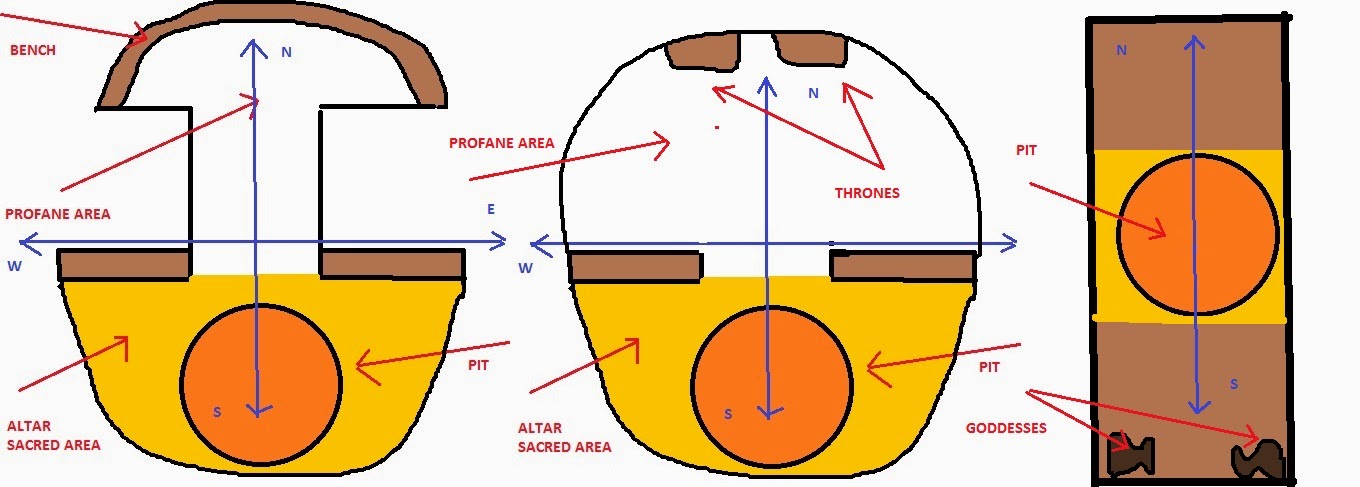

The pits are all shaped in the form of an ellipse or rough trapezoid. The settlement structure looks something like this:

Wszystkie dziury mają kształt elipsy lub nierównego trapezu. Struktura osadnicza wygląda mniej więcej tak:

There is little detailed information on the spatial distribution of features within Starčevo-Körös-Criş sites. Only a few sites have been spatially excavated. These enable us to better understand the internal structure of these sites and to interpret areas of activities. At each of these sites, almost all of the structures excavated were semi subterranean. And it seems that they all follow the same radial spatial organization of the settlement found in Blagotin. In the Foeni-Salaş site five small structures were found distributed in semicircle around a larger structure. The distance between each of the small structures was more or less the same (about 20 m), and the distance between the central and peripheral structures was about 10 m. Such a distribution of Early Neolithic features was found long before this, albeit it was not recognized as such. Vasić in his early excavations in the basal levels at Vinča found a similar distribution of Starčevo pit features – a large central pit house surrounded by an open space of about 10 m and a ring of peripheral smaller pit houses. This shows that at Blagotin we see emergence of a new culture previously not seen in Evroasia, the Starčevo culture which should really be called Blagotin culture, and the Culture which will later become the seed from which the famous metallurgical Vinča culture will develop.

Interestingly this type of settlements continue to be built in Central Europe until the medieval times by Slavic people.

Niewiele jest szczegółowych informacji na temat przestrzennego rozmieszczenia obiektów w różnych założeniach architektonicznych kultury Starčevo-Körös-Criş. Tylko kilka miejsc zostało odkrytych przestrzennie. Dzięki nim możemy lepiej zrozumieć wewnętrzną strukturę tego założenia i interpretować obszary działań. W każdym z tych miejsc prawie wszystkie wykopane konstrukcje były częściowo podziemne. I wydaje się, że wszystkie one układają się w radialną przestrzenną organizację osadnictwa podobnie jak znalezionego w Blagotinie. W miejscu Foeni-Salaş znaleziono pięć małych struktur rozmieszczonych w półkolu wokół większej struktury. Odległość pomiędzy każdą z małych struktur była mniej więcej taka sama (około 20 m), a odległość między strukturą centralną i peryferyjną wynosiła około 10 m. Taki rozkład cech z czasów wczesnego neolitu został znaleziony na długo przedtem, chociaż nie został rozpoznany jako właśnie taki. Vasić w swoich wczesnych wykopaliskach na poziomach podstawowych w Vinča odkrył podobną dystrybucję rysów w Starčevo – duży centralny wgłębiony dom otoczony otwartą przestrzenią o długości około 10 m i pierścieniem mniejszych domków peryferyjnych. To pokazuje, że w Blagotinie widzimy pojawienie się nowej kultury, której wcześniej nie widziano w Euroazji, a kultura Starčevo, tak naprawdę powinna być nazwana kulturą Blagotin, oraz jest to ta kultura, która stanie się zalażkiem późniejszej z którego rozwinie się słynna metalurgiczna kultura Vinča.

Co ciekawe, tego typu osiedla są nadal budowane w Europie Środkowej aż do czasów średniowiecza przez ludność słowiańską.

Early Slavic settlements were no larger than 0.5 to 2 hectares. Settlements were often temporary, perhaps a reflection of the itinerant form agriculture they practiced. Settlements were often located on river terraces. The largest proportion of settlement features were the sunken buildings, called Grubenhäuser in German, or poluzemlianki in Russian, zemunice in Serbian. They were erected over a rectangular pit and varied from four to twenty square meters of floor area, which could accommodate a typical nuclear family. Each house contained a stone or clay oven in one of the corners, a defining feature of the dwellings throughout Eastern Europe. On average, each settlement consisted of fifty to seventy individuals. Settlements were structured in specific manner; there was a central, open area which served as a „communal front” where communal activities and ceremonies were conducted. The settlement was polarized, divided into a production zone and settlement zone.

In Blagotin we find several overlapping phases of the settlement development. The earliest feature of the site is a 2,5 meter deep sacrificial pit, around which the temple was later built. At the bottom of the pit archaeologists have found a ritually broken deer scull with separated mandibles positioned at a certain angle.

Wczesne osady słowiańskie nie były większe niż 0,5 do 2 hektarów. Osady były często tymczasowe, co być może jest odzwierciedleniem wędrownego rolnictwa, które uprawiali. Osiedla często znajdowały się na tarasach rzecznych. Największą część cech osadniczych stanowiły budowle wgłębione, zwane Grubenhäuser w języku niemieckim, lub półziemianki w języku rosyjskim, zemunice w języku serbskim. Zostały one wzniesione nad prostokątnym otworem i miały od czterech do dwudziestu metrów kwadratowych powierzchni podłogi, która mogła pomieścić typową rodzinę neolityczną. W każdym domu znajdował się piec z kamienia lub gliny w jednym z rogów, co stanowiło charakterystyczną cechę mieszkań w całej Europie Wschodniej. Średnio każda osada liczyła od pięćdziesięciu do siedemdziesięciu osób. Założenia te były zorganizowane w określony sposób; istniał centralny, otwarty obszar, który służył jako „wspólna przestrzeń”, gdzie odbywały się wspólne czynności i ceremonie. Osada była spolaryzowana, podzielona na strefę produkcyjną i strefę osadniczą.

W Blagotin znajdujemy kilka pokrywających się faz rozwoju osadnictwa. Najwcześniejszym obiektem tego miejsca jest 2,5-metrowy dół ofiarny, wokół którego świątynia została później zbudowana. Na dnie wykopu archeolodzy znaleźli rytualnie połamaną czaszkę jelenia z oddzielonymi żuwaczkami ustawionymi pod określonym kątem.

Official theory is that this seems to connect the Starčevo culture to the much older Paleolithic deer cultures of Europe from the time before the last Ice Age. This makes Starčevo culture a link between the Paleolithic Mesolithic Hunter gatherer cultures and Neolithic agrarian cultures. This could also be an indicator of the mixing between the local European hunter gatherers and the incoming Levantine farmers. It is possible that the Blagotin culture is a product of this mix.

Deer is also a very important symbol found in in many agrarian cultures which come after Starčevo cultures.

Why deer? The Deer is a symbol of the sun, summer, repeating seasons, growth an waning and eternal life. In the Balkans it is still believed that the deer is an animal which guides the dead to the underworld, that it is an animal which can cross the boundary between the worlds. Like the sun which spends the day in our world and the night in the underworld.

But it was probably deer which lead hunter gatherers to the wild grain in the first place. It was hunters observing deer eating wild grain who first got the idea to try to eat it themselves. And believe or not, it was deer mandibles which were used as the first sickles for harvesting first wild and later domesticated grain. So placing sickles at the bottom of the sacrificial pit at the centre of the grain farmer’s temple suddenly makes a lot of sense. And this also explains why deer is found as a symbol in many agrarian cultures.

I talked about the development of sickles from deer mandibles in my post „Ri – to cut with something toothed„.

A thick ash deposits were found in the pit showing that the offerings were burned, that the cult was in a way related to fire. This is another indicator that the cult practiced in Blagotin was a sky cult, and that the deity worshiped was the sun, in his fiery form. In the ash, the remains of a human infant were interred. The remains from the pit also included extremely large numbers of the bones of young female animals. This points to the cult being not just solar cult but also a fertility cult, which is what you would expect an agricultural cult to be.

The sacrificial pit was surrounded with a zigzag line. There is no exact drawing of the pit but it probably looked like this:

Oficjalna teoria mówi, że wydaje się to wiązać kulturę Starčevo ze znacznie starszymi paleolitycznymi kulturami łowców jeleni w Europie od czasów sprzed ostatniej epoki lodowcowej. To sprawia, że kultura Starčevo jest łącznikiem między paleolitycznymi kulturami zbieraczy mezolitycznych łowców a kulturami agrarnymi neolitycznymi. (Staro-europejscy łowcy – haplogrupa Y-DNA I1 lub I2, a neolityczni rolnicy przybysze to R1a i R1b. CB). Może to być również wskazówką mieszania się miejscowych europejskich zbieraczy myśliwych z przychodzącymi lewantyńskimi rolnikami. Możliwe, że kultura Blagotin jest produktem tej mieszanki.

Jeleń jest również bardzo ważnym symbolem znajdującym się w wielu kulturach agrarnych, które pochodzą od kultur Starčevo.

Dlaczego jeleń? Jeleń jest symbolem słońca, lata, powtarzających się pór roku, narastającego zanikającego i wiecznego życia. Na Bałkanach nadal uważa się, że jeleń jest zwierzęciem, które prowadzi zmarłych do podziemnego świata, że jest zwierzęciem, które może przekroczyć granicę między światami. Jak słońce, które spędza dzień w naszym świecie i noc w zaświatach.

Ale to prawdopodobnie jelenie doprowadziły łowców zbieraczy do odkrycia dzikich zbóż. To myśliwy obserwował jelenia jedzącego dzikie ziarno, a któryś z nich wpadł na pomysł, aby spróbować je zjeść. I wierzcie lub nie, to żuchwy jelenie były używane jako pierwsze sierpy do zbierania pierwszych dzikich i później udomowionych ziaren. Zatem umieszczanie sierpów na dnie dołu ofiarnego w centrum świątyni rolnika zbożowego nagle ma wiele sensu. Wyjaśnia to również, dlaczego jelenie można znaleźć jako symbol w wielu kulturach agrarnych.

Opowiadałem o rozwoju sierpów z żuchw jelenia w moim artykule „Ri – do przecięcia z czymś ząbkowanym”.

W studzience znaleziono grube warstwy popiołu wskazujące, że ofiary zostały spalone, że kult był w pewnym sensie związany z ogniem. Jest to kolejny wskaźnik, że kult praktykowany w Blagotin był kultem nieba, a bóstwo czczone to słońce w jego ognistej formie. W popiele zostały pochowane szczątki ludzkiego niemowlęcia. Szczątki z dołu również zawierały wyjątkowo dużą liczbę kości młodych samic. Wskazuje to na to, że kult jest nie tylko kultem słonecznym, ale także kultem płodności, czego można by się spodziewać kult rolniczy.

Ofiarny dół otoczony był linią zygzakowatą. Nie ma dokładnego rysunku dołu, ale prawdopodobnie wyglądało to tak:

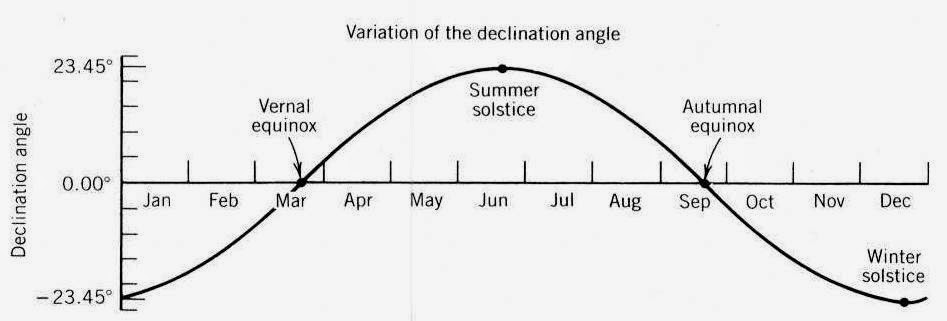

Looks familiar? Looks like the sun? This shows that the zigzag line later found in Vinča deposits is closely connected with the cult and has a religious significance. And we know exactly what this zigzag line means. The zigzag line is a symbol of the solar ecliptic. The solar ecliptic is the apparent path of the Sun on the celestial sphere. The solar ecliptic is the line that defines the seasons, that defines the climate, that governs agriculture.

Wygląda znajomo? Wygląda jak słońce? To pokazuje, że zygzakowata linia znaleziona później w osadach Vinča jest ściśle związana z kultem i ma znaczenie religijne. I dokładnie wiemy, co oznacza ta zygzakowata linia. Linia zygzakowata jest symbolem ekliptyki słonecznej. Ekliptyka słoneczna jest pozorną ścieżką Słońca w sferze niebieskiej. Ekliptyka słoneczna to linia określająca pory roku, określająca klimat, który reguluje rolnictwo.

For people who arrive from the Levant, European winters must have been quite a shock. The dying of the sun’s fire must have been a major cause for concern and all necessary steps had to be taken to ensure that it gets rekindled every spring. Including sacrifices….Were the sacrifices which were made in the Blagotin temple made to ensure that the Sun’s fire gets rekindled again? Were they performed at maybe a winter solstice?

If you are a farmer, the further north you go from the equator the more important it becomes to understand the behavior of the sun. Which eventually lead to the development of the solar astronomy and solar agricultural cults. Is it possible that in Blagotin we see the emergence of the solar astronomy and the emergence of the Solar cults? Is Blagotin temple not just the first temple but also the first solar temple? I believe so and I believe that the the proof for this lies in the temple itself, or more precisely its orientation.

The temple went through 7 phases of development. Through all of these phases the temple retained the same sacred altar space which was built around the sacrificial pit. The profane part of the temple undertook several structural changes BUT THE TEMPLE AS A WHOLE WAS ALWAYS ORIENTED EXACTLY NORTH – SOUTH.

There are three ways to orient a building exactly north south. One way is to use a compass to determine the exact north. In the 7th millennium bc, this was highly unlikely to have happened. The other two ways are:

1. Find the north star and orient your building to it. For this you need to know what the north star is and that it is a static star pointing north, which means that you need to be versed in star astronomy.

2. Determine the exact points where the sun rises on the days of the winter and summer solstice. Bisect the arch between these two points into half. This will determine the point where the sun will rise on the equinoxes, the true east. Draw a line pointing east – west

Draw an orthogonal line which will point north – south Align your temple with this line…To be able the align their temple north – south, you need to know a lot about the sun’s apparent movement in the sky which means that you need to be versed in solar astronomy.

In order to be able to orient their temple north – south, he people from Blagotin needed to be be able to do one of the above, which would mean that the people from Blagotin were not just farmers but accomplished astronomers and mathematicians. Probably the first people in the world to create a temple aligned with solar cardinal points.

Dla ludzi, którzy przybywają z Lewantu, europejskie zimy musiały być szokiem. Umierania ognistego słońca musiały być poważnym powodem do niepokoju i trzeba było podjąć wszystkie konieczne kroki, aby odrodzić je każdej wiosny. Łącznie z ofiarami … Czy ofiary, które zostały wykonane w świątyni Blagotin, miały na celu sprawienie, by ogień Słońca ponownie się rozpalił? Czy były wykonywane w czasie zimowego przesilenia?

Jeśli jesteś rolnikiem, im dalej na północ od równika, tym ważniejsze staje się zrozumienie zachowania słońca. Co ostatecznie doprowadziło do rozwoju astronomii słonecznej i kultów słonecznych w rolnictwie. Czy to możliwe, że w Blagotinie widzimy pojawienie się astronomii słonecznej i pojawienie się kultów słonecznych? Czy świątynia Blagotin to nie tylko pierwsza świątynia, ale także pierwsza świątynia słoneczna? Wierzę w to i wierzę, że dowód na to leży w samej świątyni, a dokładniej w jej orientacji.

Świątynia przeszła 7 faz rozwoju. We wszystkich tych fazach świątynia zachowała tę samą świętą przestrzeń ołtarza, która została zbudowana wokół miejsca ofiarnego. Część świątyni stanowiąca sferę profanum przeszła kilka zmian strukturalnych, ALE ŚWIĄTYNIA JAKO CAŁOŚĆ POZOSTAŁA ZAWSZE ZORIENTOWANA DOKŁADNIE w linii PÓŁNOC – POŁUDNIE.

Istnieją trzy sposoby orientowania budynku dokładnie na linię północ – południe. Jednym ze sposobów jest użycie kompasu do określenia dokładnej północy. W 7. tysiącleciu pne było to bardzo mało prawdopodobne. Pozostałe dwa sposoby to:

1. Znajdź gwiazdę północną i zorientuj budynek na nią. W tym celu musisz wiedzieć, czym jest gwiazda północna i czy jest to statyczna gwiazda wskazująca północ, co oznacza, że musisz być zorientowany w astronomii gwiazd.

2. Określ dokładne punkty, w których słońce wschodzi w dniach przesilenia zimowego i letniego. Przecięcie łuku między tymi dwoma punktami na pół. To określi punkt, w którym słońce wzejdzie w równonocach, prawdziwym wschodzie. Narysuj linię wskazującą wschód – zachód

Narysuj prostopadłą linię, która wskaże północ – południe. Wyrównaj swoją świątynię z tą linią … Aby móc wyrównać ich świątynię na północ – południe, musisz dużo wiedzieć o widocznym ruchu słońca na niebie, co oznacza, że musisz być zorientowanym w astronomii słonecznej.

Aby móc zorientować swoją świątynię na północ od południa, ludzie z Blagotin musieli być w stanie wykonać jedno z powyższych, co oznaczałoby, że ludzie z Blagotin byli nie tylko rolnikami, ale także astronomami i matematykami. Prawdopodobnie jako pierwsi ludzie na świecie stworzyli świątynię wyrównaną z słonecznymi punktami kardynalnymi.

Originally it was shaped as a mushroom (penis) where the semicircular part had a bench build along its its edge where people worshiping in the temple, could sit. Later on the bench disappears and instead of it we find two high thrones. People sitting on these thrones would have looked directly towards the altar and the south. Then the mushroom (penis) shaped area was remodeled in such a way that the whole temple including both the sacred and the profane area together resembles a Greek letter theta. Eventually the whole temple was completely changed. The profane part was covered with a thick layer of daub and a new a long narrow building oriented north – south was constructed in place of the old temple. The altar was in the center of the new building and flanking the south entrance were two unusual large (30 cm high) figurines which looked like this.

Pierwotnie to było ukształtowane jako grzyb (penis), gdzie półkolista część miała ławkę zbudowaną wzdłuż jej krawędzi, na której mogli siedzieć ludzie czczący w świątyni. Później ławka znika, a zamiast niej znajdujemy dwa wysokie trony. Ludzie siedzący na tych tronach patrzyliby wprost na ołtarz i południe. Następnie obszar w kształcie grzyba (penisa) został przebudowany w taki sposób, że cała świątynia, obejmująca zarówno obszar sacrum, jak i profanum, przypomina grecką literę theta. W końcu cała świątynia została całkowicie zmieniona. Część nieprzyzwoita pokryta była grubą warstwą kiczu, a w miejscu starej świątyni zbudowano nowy długi, wąski budynek zorientowany na północ – południe. Ołtarz znajdował się pośrodku nowego budynku, a po południowej stronie były dwie niezwykłe, duże (30 cm wysokości) figurki, które wyglądały w ten sposób.

They had over emphasized gluts stylized short legs and according to the early interpretation offered by the archaeologists, stylized deer head. This means that the sculpture consisted of the female principle (lower part of female body) extending into the male principle (deer head the top part of the body). The „goddesses” were found „lying on their faces” and I believe that this gives us an important clue for deciphering their meaning. Recently archaeologists made copies of these goddess figurines using the same clay from which the original figurines were made. Then they fired the figurines using the reconstructed early neolithic oven.

Podkreślali glutowate stylizowane krótkie nogi i, zgodnie z wczesną interpretacją archeologów, stylizowaną głowę jelenia. Oznacza to, że rzeźba składa się z zasady żeńskiej (dolna część kobiecego ciała) rozciągającej się na męską zasadę (głowa jelenia w górnej części ciała). „Boginie” zostały znalezione „leżące na twarzach” i wierzę, że to daje nam ważną wskazówkę do rozszyfrowania ich znaczenia. Niedawno archeolodzy wykonali kopie tych figurek bogini przy użyciu tej samej gliny, z której wykonano oryginalne figurki. Następnie wypalili figurki za pomocą sposobu zrekonstruowanego z wczesnego neolitu.

On the last picture, the goddesses were „laid on their faces”. And here the meaning of these goddesses becomes clear. They are half women in the „kneeling, on all four” position, ready to be mounted, penetrated and fertilized, like any other female animal, from behind. So the bottom part is not just a woman but a female of any domestic kind which we want to fertilize in order to produce offspring. In this position the upper part of the body, the male part, penetrates the earth, like a plow. If anyone wanted to make a symbol that links fertility and farming (grain growing and cattle razing), they couldn’t have made a better one. These figurines are probably the first fertility idols directly linked to agriculture. They create symbolic equalization between a plow and a penis and between plowing and copulating, between sex and working the land.

These figurines are not the only important objects found on Blagotin site.

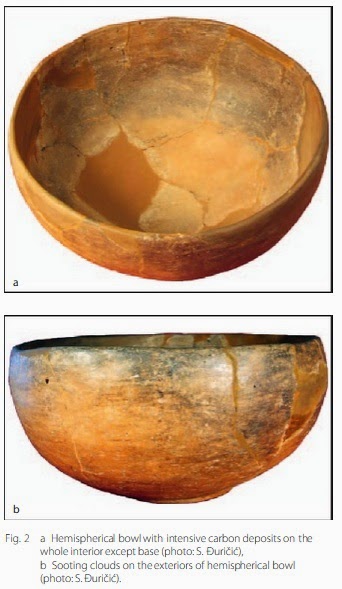

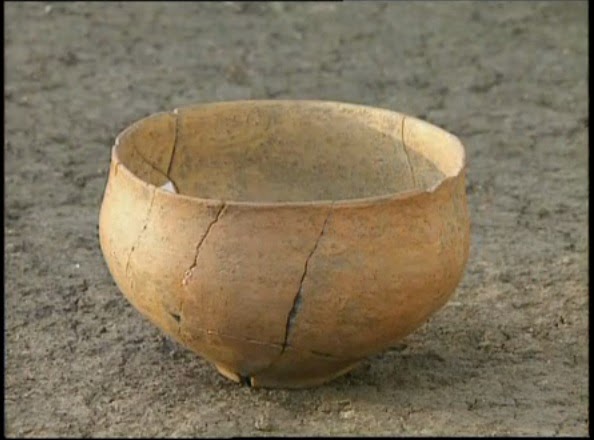

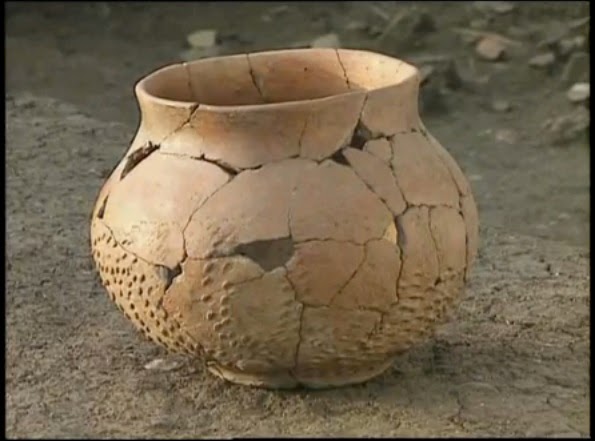

All of the excavated pit houses contained extraordinarily large amount of ceramic fragments and whole ceramic vessels and figurines. The biggest number of ceramic fragments was found in the temple which shows that the ceramic artifacts were brought to the temple as offerings and were possibly ceremonially broken inside the temple. On only 30 square meters which have been excavated so far, archaeologists have found 16,000 ceramic fragments. Ceramic vessels found in the pit houses range from ordinary domestic utensils to exquisitely ornate ceremonial vessels.

Na ostatnim obrazie boginie „leżały na ich twarzach”. I tutaj znaczenie tych bogiń staje się jasne. Są pół kobietami w pozycji „na kolanach, na wszystkich czterech”, gotowej do penetracji i zapłodnienia, jak każde inne zwierzę, od tyłu. Tak więc dolna część to nie tylko kobieta, ale kobieta jakiejkolwiek rodziny, którą chcemy zapłodnić, aby posiadać potomstwo. W tej pozycji górna część ciała, część męska, przenika do ziemi, jak pług. Jeśli ktoś chciałby stworzyć symbol łączący płodność z rolnictwem (uprawa zbóż i pokrywanie bydła), nie mógłby stworzyć lepszego obrazu. Te figurki są prawdopodobnie pierwszymi idolami płodności bezpośrednio związanymi z rolnictwem. Tworzą symboliczną równowagę między pługiem i penisem oraz pomiędzy orką a kopulacją, między seksem a pracą na roli.

Te figurki nie są jedynymi ważnymi obiektami znalezionymi na stanowisku Blagotin.

Wszystkie wykopane domy wgłębione zawierały wyjątkowo dużą ilość ceramicznych fragmentów i całych ceramicznych naczyń i figurek. Najwięcej ceramicznych fragmentów znaleziono w świątyni, co pokazuje, że ceramiczne artefakty zostały wniesione do świątyni jako ofiary i prawdopodobnie zostały ceremonialnie rozbite wewnątrz świątyni. Na jedynych 30 metrach kwadratowych, które zostały dotychczas przebadane, archeolodzy znaleźli 16 000 ceramicznych fragmentów. Ceramiczne naczynia znalezione w domach mniejszych rozciągają się od zwykłych naczyń domowych do wykwintnie ozdobnych statków ceremonialnych.

One of the ceramic vessels found on the site is an unusual cross shaped bowl shown here with a ceramic altar and ceramic votive grains of wheat also found on the site.

Jednym z naczyń ceramicznych znalezionych na miejscu jest niezwykła misa w kształcie krzyża pokazana tutaj z ceramicznym ołtarzem i ceramicznymi wotywnymi ziarnami pszenicy również znalezionymi na miejscu.

There are two articles published about the pottery from Blagotin. A use analysis for the pottery from one of the houses from the site can be found in the article entitled: „Beginnings – New Research in the Appearanceof the Neolithic between Northwest Anatoliaand the Carpathian Basin„. A possibility of early beer production was explored in the article entitled „Non-abrasive Pottery Surface Attrition: Blagotin Evidence„. Both were published by Jasna Vuković from Belgrade university.

Apart from the ceramic vessels archaeologist have found many ceramic altars like the one on the above picture or this one:

Są dwa artykuły na temat ceramiki od Blagotin. Analiza wykorzystania ceramiki z jednego z domów na stanowisku znajduje się w artykule zatytułowanym: „Początki – nowe badania o tym jak wyglądał neolit między Anatolią Północno-Zachodnią a Zagłębiem Karpackim”. Możliwość wczesnej produkcji piwa została zbadana w artykule zatytułowanym „Ścieranie powierzchni ściernic niezcieralnych: Dowody blagotynowe”. Obie zostały wydane przez Jasnę Vuković z uniwersytetu w Belgradzie.

Oprócz ceramicznych naczyń archeologowie znaleźli wiele ołtarzy ceramicznych, takich jak ten na powyższym obrazku lub ten:

A very important find is a very large number of clay models of grains of wheat, which you can see on the above picture with the cross shaped vessel and the altar. These clay seeds were left in the temple as votive offerings. This confirms that the people who lived in Blagotin were grain farmers and that their cult was grain fertility cult. These clay grain sees are found on other Starčevo culture sites but never in this number.

Bardzo ważnym odkryciem jest bardzo duża liczba modeli glinianych ziaren pszenicy, które możecie zobaczyć na powyższym zdjęciu z naczyniem w kształcie krzyża i ołtarzem. Te nasiona z gliny pozostały w świątyni jako wotywne ofiary. To potwierdza, że ludzie, którzy mieszkali w Blagotin, byli rolnikami zbożowymi, a ich kult był kultem płodności ziarna. Widły z gliny znajdują się na innych stanowiskach kultury Starčevo, ale nigdy w tej liczbie.

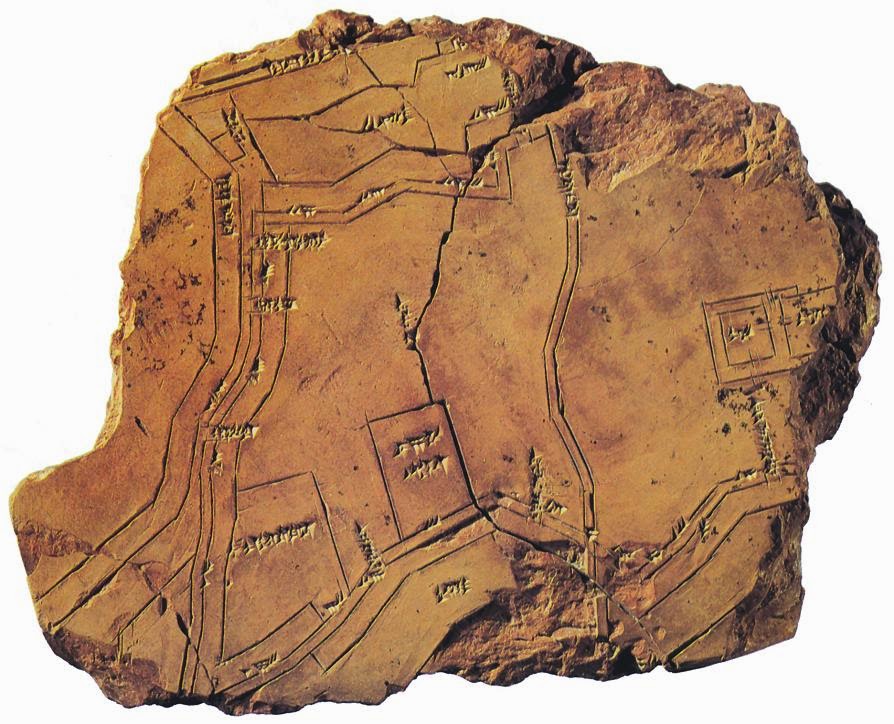

One of the clay seed models has engraved the plan of the village with the temple as the central object. The plan closely corresponds to the actual layout of the part of the Blagotin village.

na jednym z modeli ziaren gliny wygrawerowano plan wioski ze świątynią jako centralnym obiektem. Plan ściśle odpowiada faktycznemu układowi części wioski Blagotin.

This is the earliest known town map in Europe and possibly the oldest map in the world. Until very recently this was undobtedly true. The two next oldest maps were the „Ga-Sur at Nuzi” map and „Nippur” map.

The Ga-Sur at Nuzi map is a Babylonian clay tablet that was unearthed in 1930 at the excavated ruined city of Ga-Sur at Nuzi [Yorghan Tepe], near the towns of Harran and Kirkuk, 200 miles north of the site of Babylon [present-day Iraq]. Small enough to fit in the palm of your hand (7.6 x 6.8 cm), most authorities place the the date of this map-tablet from the dynasty of Sargon of Akkad (2,300-2,500 B.C.); although, again, there is the conflicting date offered by the distinguished Leo Bagrow of the Agade Period (3,800 B.C.). The surface of the tablet is inscribed with a map of a district bounded by two ranges of hills and bisected by a water-course. This particular tablet is drawn with cuneiform characters and stylized symbols impressed, or scratched, on the clay. Inscriptions identify some features and places. In the center the area of a plot of land is specified as 354 iku [about 12 hectares], and its owner is named Azala. None of the names of other places can be understood except the one in the bottom left comer. This is Mashkan-dur-ibla, a place mentioned in the texts from Nuzi as Durubla. By the name, the map is identified as of a region near present-day Yorghan Tepe (Ga-Sur at the time, the name Nuzia 1,000 years later), although the exact location is still unknown.

Jest to najstarsza znana mapa miasta w Europie i prawdopodobnie najstarsza mapa świata. Od niedawna jest to niewątpliwa prawda. Dwie najstarsze dotychczas mapy to mapa „Ga-Sur at Nuzi” i mapa „Nippur”.

Mapa Ga-Sur na mapie Nuzi jest babilońską tabliczką z gliny odkrytą w 1930 r. W odkopanym mieście Ga-Sur w Nuzi [Yorghan Tepe], w pobliżu miast Harran i Kirkuk, 200 mil na północ od Babilonu [dzisiejszy Irak]. Wystarczająco mała, aby zmieściła się w dłoni (7,6 x 6,8 cm), większość autorytetów umieszcza datę tej mapy-tabliczki w czasach dynastii Sargona z Akkadu (2300-2.500 KB); chociaż, znowu, jest sprzeczna data oferowana przez wybitnego Leo Bagrowa z Agade Period (3800 BC). Na powierzchni tabliczki widnieje mapa dzielnicy otoczonej dwoma pasmami wzgórz, podzielona przez cieśninę. Ta konkretna tabliczka jest rysowana za pomocą znaków klinowych i stylizowanych symboli wybitych lub porysowanych na glinie. Napisy identyfikują niektóre funkcje i miejsca. W centrum obszar działki jest określony jako 354 iku [około 12 hektarów], a jego właścicielem jest Azala. Żadne z nazw innych miejsc nie może być zrozumiane, z wyjątkiem jednego w dolnym lewym rogu. To Mashkan-dur-ibla, miejsce wspomniane w tekstach Nuziego jako Durubla. Według nazwy mapa jest identyfikowana jako region w pobliżu dzisiejszego Yorghan Tepe (w tym czasie Ga-Sur, nazwa Nuzia 1000 lat później), chociaż dokładna lokalizacja jest wciąż nieznana.

The Nippur map is a fragment of a clay tablet which contains a city map, which was dated to 1500 BC. The clay tablet depicts the temple of Enlil, a city park, the city wall including its gates, along with a canal and the river Euphrates. The individual objects on this map were already labelled, in a Sumerian cuneiform.

Mapa Nippur jest fragmentem glinianej tabliczki, który zawiera mapę miasta, która została datowana na 1500 pne. Tabliczka z gliny przedstawia świątynię Enlil, park miejski, mur miejski wraz z bramami, kanał i rzekę Eufrat. Poszczególne obiekty na tej mapie zostały już oznaczone w sumeryjskim pismie klinowym.

Both of these maps are much younger than the Blagotin grain map. However we now have a close competition for the oldest map in the world between the Blagotin grain map and the Çatalhöyük wall map. During the excavation of Çatalhöyük in Anatolia a wall painting was uncovered that is approximately nine feet long and has an in situ radiocarbon date of 6,200 + 97 B.C. It is believed that the map depicts a town plan, matching Çatalhöyük itself, showing the congested „beehive” design of the settlement and displaying a total of some 80 buildings. In the foreground is a town arising in graded terraces closely packed with rectangular houses. Behind the town an erupting volcano is illustrated, its sides covered with incandescent volcanic bombs rolling down the slopes of the mountain. Others are thrown from the erupting cone above which hovers a cloud of smoke and ashes.

Obie mapy są znacznie młodsze niż mapa na ziarnie z Blagotinu. Jednak teraz mamy ścisłą rywalizację o najstarszą mapę świata między mapą zbożową Blagotin a mapą ścienną Çatalhöyük. Podczas wykopalisk Çatalhöyük w Anatolii odkryto malowidło ścienne o długości około 9 stóp i datę radiowęglowej in situ 6 200 + 97 ° C. Uważa się, że mapa przedstawia plan miasta, pasujący do samego Calatalhöyük, pokazujący zatłoczone „ule” projekt osady i wyświetlający w sumie około 80 budynków. Na pierwszym planie jest miasteczko powstałe na stopniowanych tarasach, gęsto upakowanych prostokątnymi domami. Za miastem zilustrowany jest wybuchający wulkan, którego boki pokryte są żarzącymi się wulkanicznymi bombami toczącymi się po zboczach góry. Inne są wyrzucane ze stożka eksplozji, nad którym unosi się chmura dymu i popiołu.

Another important type of artifacts found in Blagotin are amulets.

Innym ważnym rodzajem artefaktów znalezionych w Blagotinie są amulety.

In her work „The Blagotin amulets and their place in the early Neolithic of the central Balkans” Jasna Vukovic says:

W swojej pracy „Amulety z Blagotina i ich miejsce we wczesnym neolicie środkowych Bałkanów” Jasna Vukovic mówi:

On this graph you can see the distribution of these amulets. Divostin the site with the second highest number of amulets is the site closest to Blagotin. The further away you go from Blagotin, the fewer amulets you find.

Na tym wykresie widać rozkład tych amuletów. Divostin stanowisko z drugą największą liczbą amuletów to obszar najbliżej Blagotinu. Im dalej od Blagotinu, tym mniej amuletów znajdziesz.

Do these amulets remind anyone of the Gobelki Tepe columns? Did part of the Gobelki Tepe people and religion find its way to Blagotin?

Another large group of objects found in Blagotin are votive models of domestic animals, which were deposited in the temple as offerings. This means that the people living in Blagotin were both grain farmers and herders.

Czy te amulety przypominają którąkolwiek z kolumn Gobelki Tepe? Czy część ludzi z religii Gobelki Tepe trafiła do Blagotina?

Inną dużą grupą przedmiotów znalezionych w Blagotin są wotywne modele zwierząt domowych, które zostały złożone w świątyni jako ofiary. Oznacza to, że ludzie żyjący w Blagotin byli zarówno hodowcami zbóż, jak i pasterzami.

What is very interesting is that we find the same types of domesticated animals figurines in Catalhoyuk at the roughtly the same time. Nearly 2,000 figures have been unearthed at Catalhoyuk. They were dated to about 7000 BC. The majority are representations of cattle or sheep and goats.Like these ones:

Bardzo interesujące jest to, że w tym samym czasie znajdujemy w Katalonii podobne rodzaje figurek zwierząt udomowionych. Prawie 2000 postaci zostało odkrytych w Catalhoyuk. Zostały one datowane na około 7000 pne. Większość to przedstawienia bydła lub owiec i kóz. Podobne:

Does this suggest that the people who settled in Blagotin came from Catalhoyuk? Or that they were culturally connected with the people from Catalhoyuk?

In Blagotin, archaeologists also found grinding stones. Unfortunately I don’t have any pictures of these grinding stones but they probably looked like this one.

Czy to sugeruje, że ludzie, którzy osiedlili się w Blagotin, pochodzili z Catalhoyuk? Lub, że byli kulturalnie połączeni z ludźmi z Catalhoyuk?

W Blagotinie archeolodzy znaleźli również kamienie mielące. Niestety nie mam zdjęć tych szlifujących kamieni, ale prawdopodobnie wyglądały jak ten.

Flotation technique also yielded a lot of grain seeds which were extremely big for that period and were in size comparable to the modern sorts of wheat. Antler plows and other neolithic agricultural tools were also found on the site. After taking into the account all the evidence from the site archaeologists working on the site concluded that the people living in Blagotin probably grew enough good quality grains to make wheat bread.

Archaeologists have also found other bone and stone tools and blades:

Technika flotacji dała również wiele nasion zbóż, które były wyjątkowo duże w tym okresie i były wielkości porównywalne do nowoczesnych rodzajów pszenicy. Pługi poroża i inne neolityczne narzędzia rolnicze również zostały znalezione na miejscu. Po uwzględnieniu wszystkich dowodów z miejsca pracy archeolodzy pracujący nad tym założeniem stwierdzili, że ludzie żyjący w Blagotinie prawdopodobnie wyhodowali dość dobrej jakości ziarna, aby zrobić chleb pszenny.

Archeolodzy znaleźli również inne narzędzia i ostrza z kości i z kamieni:

Archaeologists also found a lot of jewelry on the site like these necklaces and bracelets:

Archeolodzy znaleźli również wiele biżuterii na ststanowisku, takich jak naszyjniki i bransoletki:

Some jewelry found in the temple resembles ones found in the Transilvania. Some other material came from Kosovo and Black Sea coast. This suggests that Blagotin was an important regional (Balkan) and maybe even Central European religious center where people came at certain part of the year to celebrate and pray. Maybe at winter solstice. Or at harvest time.

And so this is Blagotin, probably the most important archaeological site you have never heard of. The site where European Neolithic agricultural society was born. The site where we find the oldest temple in Europe and the second (or the third depending how you count) oldest temple in the world. The site where we find the oldest evidence of the complex astronomical and mathematical knowledge required to determine solstices and equinoxes and align the temple to cardinal points. The site where we find first definite evidence of the development of the solar agricultural fertility cult. The site where we find the oldest town map in Europe and the oldest (or the second depending how you count) town map in the world.

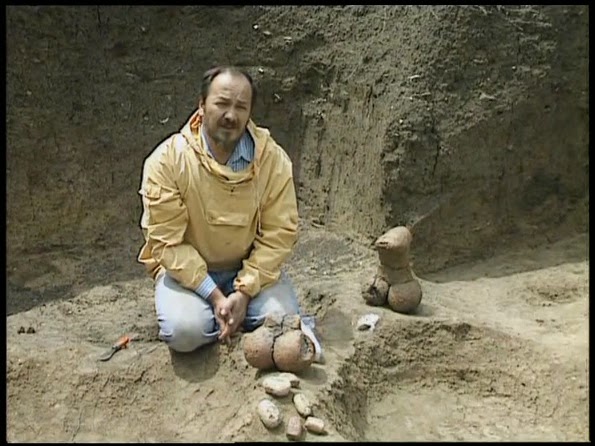

The Blagotin site was discovered by Dr Svetozar „Nani“ Stanković just before the start of the Yugoslav civil war in 1991. This is the man himself.

Niektóre egzemplarze biżuterii znalezione w świątyni przypominają te znalezione w Transylwanii. Inne wykonane są z materiału pochodzącego z Kosowa i wybrzeża Morza Czarnego. To sugeruje, że Blagotin był ważnym regionalnym (Bałkany), a może nawet środkowoeuropejskim centrum religijnym, gdzie ludzie przychodzili w pewnej porze roku, aby świętować i modlić się. Może podczas przesilenia zimowego, lub w czasie żniw.

Blagotin to jest, prawdopodobnie najważniejsze stanowisko archeologiczne, o którym nigdy nie słyszałeś. Miejsce, w którym narodził się europejski neolityczny kult rolniczy. Wykopalisko gdzie znajduje się najstarsza świątynia w Europie i druga (lub trzecia w zależności jak liczyć) najstarsza świątynia na świecie. Założenie, gdzie znajdziemy najstarszy dowód kompleksowej wiedzy astronomicznej i matematycznej wymaganej do określenia przesileń i równonocy i wyrównania świątyni do punktów kardynalnych. Miejsce, w którym znajdujemy pierwszy wyraźny dowód rozwoju słonecznego kultu płodności w kulturze rolniczej. Stanowisko gdzie znajdziemy najstarszą mapę miasta w Europie i najstarszy (lub drugi w zależności jak liczyć) Plan miasta w świecie.

Witryna Blagotin została odkryta przez dr Svetozara „Nani” Stankovićia tuż przed rozpoczęciem jugosłowiańskiej wojny domowej w roku 1991. To jest ten człowiek.

The excavations were then continued until 1995 as a joint venture between the University of Belgrade (Serbia) and the University of Manitoba (Canada). Dr Svetozar „Nani“ Stanković (1948 – 1996) who lead the excavation, died in 1996 and the whole archaeological site was closed and forgotten??? Only 2.5% of the locality has been excavated so far. The site is not protected by Serbian government or by UNESCO. The goddess figurines are locked in the depot of the Belgrade University…

The only two papers written about the site which are written in Serbian and are which are available on the internet are „1992b Arheološka istraživanja višeslojnog praistorijskog lokaliteta Blagotin u selu Poljna istraživanja 1991 godine„. „Systematic surface collection from Blagotin„.

Believe or not the best information about the Blagotin site is contained in this three part documentary made in 1993, which features interview with the late Dr Svetozar „Nani“ Stanković.

Prace wykopaliskowe kontynuowano do 1995 r. jako wspólne przedsięwzięcie Uniwersytetu Belgradzkiego (Serbia) i Uniwersytetu w Manitobie (Kanada). Dr Svetozar „Nani” Stanković (1948 – 1996), który prowadził wykopaliska, zmarł w 1996 r., a całe stanowisko archeologiczne zostało zamknięte… i zapomniane? Do tej pory odkopano tylko 2,5% założenia. Wykopalisko nie jest chronione przez rząd Serbii lub UNESCO. Figurki bogiń są zamknięte w magazynie Uniwersytetu w Belgradzie …

Jedyne dwa artykuły napisane na temat tego stanowiska, które są napisane w języku serbskim i które są dostępne w Internecie, to: „1992b Arheološka istraživanja višeslojnog praistorijskog lokaliteta Blagotin u selu Poljna istraživanja 1991 godine”. „Systematyka obszaru kolekcji w Blagotinie”.

Wierzcie lub nie, najlepsze informacje na temat wykopaliska Blagotin zawarte są w tym trzyczęściowym dokumencie z 1993 r., W którym znajduje się wywiad z nieżyjącym dr Svetozarem „Nani” Stankovićiem.

I extracted all the relevant information in this article. There is no point looking on the net for more info. This is it. This is all there is…Sad.There are talks about reopening of the excavation on the site this year, 20 years after the site was forgotten.

Wyciągnąłem wszystkie istotne informacje w tym artykule. Nie ma sensu szukać w Sieci po więcej informacji. To jest to. To wszystko, co jest … Smutne.

W tym roku mówi się o ponownym otwarciu wykopalisk na tym terenie, 20 lat po tym, jak stanowisko zostało zapomniane.

źródło: http://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2015/03/blagotin.html

tłumaczenie: Czesław Białczyński