POLSKA – ROSJA – i Świętobliwy Issa – czyli co robił przez 18 lat nieuznany przez Żydów Mesjasz

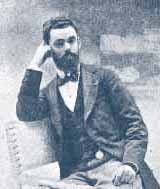

O Mikołaju Notowiczu wiele sobie nie poczytacie ani po rosyjsku ani po polsku ani po angielsku. Najbardziej jest znane to co odkrył, natomiast o nim samym niewiele wiadomo – do tego stopnia że nieznana jest nawet data jego śmierci – przynajmniej w Wikipedii. Wiadomo, że był Kozakiem, szlachcicem co oznacza że był najprawdopodobniej Polakiem albo Rusinem-Ukraińcem, a nie żadnym Rosjaninem. Jako szlachcic Rosjanin byłby bowiem bojarem.

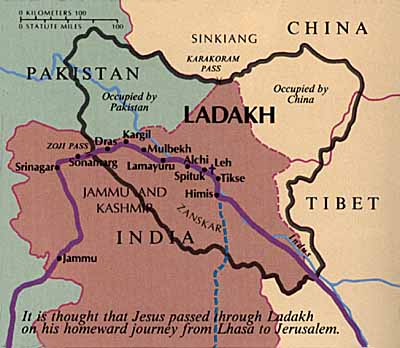

Dodatkowo cała ta historia wiąże się z terytorium Tybetu – TuBądu/TuBytu i z Ziemią Lodu (Ladakh), która jak wiadomo leży po sąsiedzku z Doliną Hunza (Hunów Hakowników hg Y-DNA R1a1) i z Sistanem współczesnym. Cały ten region zasiedla zaś obficie ludność Haplogrupy Y-DNA R1a1, czyli potomkowie Prasłowian lub Słowian.

Ponieważ bardzo wiele przez stulecia zrobiono by treść książki Mikołaja Notowicza, podobnie jak „Bożyca” Bronisława Trentowskiego, nie przedostała się do publicznej wiadomości, musicie niestety przeczytać jego książkę tutaj poniżej w języku angielskim albo co najwyżej, jeśli nie znacie za dobrze tego języka, skorzystać z pomocy Google-Tłumacza.

Sekwencja tych Świąteczno-Noworocznych Życzeń dotyczaca Jezusa i odkryć Notowicza to prezent dla nas wszystkich od wielu osób, które zbiorowym wysiłkiem, w kilku krajach i w kilku narodach, w kilku językach (i w kilka wieków, jak widać, bo mamy XXI) doprowadziły do publikacji i do wiadomości ogółu owe dziwne dzieje, i ukazały światu ową tajemniczą rozgrywkę między Siłami Słońca i Księżyca (Jasności i Ciemności) zwalczającymi się zapiekle (ładne słowo i właściwe) także w kościele katolickim. Bardzo to pouczające, zwłaszcza, że wciąż mamy z ową blokadą informacyjną do czynienia, w każdym razie z próbami „opóźniania” informacyjnego, co przecież nie jest bez znaczenia.

CB

Φ

Nikołaj Notowicz (1858 – ? ) – Strażnik Wiary Słowian – Co odkrył na temat pobytu Świątobliwego Męża o imieniu Issa w Windji nad Indusem-Widjuszem i Tubądcie – Tybecie

Nikolai Notowicz – to znaczy Mikołaj Notowicz. Taki był z niego Rosjanin jak z Koziej D… Udacznaja Trubka.

Jedyny właściwie i dosyć dobry artykuł znalazłem na stronie Racjonalista.PL

Z Racjonalista.pl

http://www.racjonalista.pl/kk.php/s,1748

Jezus w Indiach

Autor tekstu: Wacław Korabiewicz

Przeglądając przebogatą literaturę religioznawczą dostrzega się w niej nieprawdopodobne wprost zaślepienie , a może tendencyjną krótkowzroczność . Najdrobniejsze szczegóły życia Chrystusa są analizowane i studiowane , podczas gdy tak niebywale ważny fakt , jak zniknięcie Jezusa na długie 18 lat i to lat najistotniejszych , bo okresu dojrzewania , lekceważy się . Przechodzi się nad tym do porządku dziennego , jakby chodziło o godzinę a nie o 18 lat .

Wszakże już jako dwunastoletni chłopak zdumiewał On bystrością umysłu . Wdaje się On w dyskurs filozoficzny z kapłanami i zadziwia pytaniami mędrców (Łukasz II,47) . Wykazuje energię i samodzielność odłączając się na trzy dni od rodziców w dużym , obcym dla siebie mieście (Łukasz II,46) . A gdy rodzice go znaleźli , robi im wymówki , że niepokoili się i szukali go ( Łukasz II,49) . I ten oto właśnie wielce zaradny , mądry chłopak , nad rozumem którego wszyscy się zdumiewali ( Łukasz II,47) , nagle znika na osiemnaście lat . Zjawia się już jako dorosły mężczyzna , a przy tym jest już doświadczonym nauczycielem i filozofem . Najdokładniejszy z Ewangelistów , św. Łukasz tę osiemnastoletnią nieobecność zbywa lakonicznym oświadczeniem : …poszedł z nimi (rodzicami) i wrócił do Nazaretu , i był im poddany (Łukasz II,51)

Co to znaczy poddany ? On , taki żywy , pełen inicjatywy , nagle stał się poddanym , synem potulnym i posłusznym ? Czyżby potrafił w ciągu 18 lat poświęcić się bez reszty ciesielskiej pracy ojca i nikt go niczego nie nauczył ?

Rzeczywiście może wygodniej nie poruszać tej dziwnej sprawy , aby nie trafić przypadkowo na jakiegoś nauczyciela . Bo jakżeby Jezus zesłany przez Boga mógł mieć profesora . Widocznie świat Wielkich Wtajemniczonych nie życzy sobie odsłaniania tej tajemnicy . Widocznie wielcy wolą , aby Jezus odszedł na osiemnaście lat donikąd i wrócił znikąd .

Tymczasem odkryte nad Morzem Martwym manuskrypty mówią wprawdzie o Mistrzu Sprawiedliwości , ale to nie mógł być Jezus , gdyż nauczyciel o którym mowa żył co najmniej 100 lat przed Jezusem . Zresztą Jezus , kiedy się objawił w roli Mesjasza , swoim postępowaniem , stylem zachowania i ubiorem daleko odbiegał od Qumrańskich mistrzów . Zgodnie ze starymi manuskryptami zachowanymi szczątkowo w klasztorach i zwojami w klasztorach indyjskich wysnuwa nam się zgoła fantastyczny wniosek . Jezus 18 lat swojego życia spędził w Indiach. Trafił tam bardzo łatwo . Jego kuzyn Jan ( zwany później Chrzcicielem )jako jedyny z jego rówieśników odpowiadał mu poziomem inteligencji i duchowości . Jan też pierwszy trafił na Esseńczyków . Między Indiami a Jerozolimą stale kursowały handlowe karawany . Ich woźnice opowiadali przechodniom o jakiś senianinach , czyli wędrujących mędrcach , o sadhu czyli zakonnikach pustelnikach . Kuzyn Jan namawiał Jezusa na udanie do Qumran , ale jezusowi nie odpowiadała surowość tej gminy , to nie była atmosfera miłości i dobra . Tam poszedł Jan , ale Jezus wiedziony ciekawością tych wszystkich opowiadanych cudów indyjskich , zapewne dołączył do jucznej karawany wielbłądów i udał się w poszukiwaniu prawdy do tych co czynią te cuda .

Jedną z pierwszych osób która znalazła jakiekolwiek pisane dowody pobytu Jezusa w Indiach był Rosjanin polskiego pochodzenia Nikołaj Notowicz . W klasztorze Moulbek w trakcie rozmowy z lamą ze zdziwieniem wysłuchał oskarżenia go jako chrześcijanina . Po kilku pytaniach okazało się że , iż lama traktując go jako przedstawiciela chrześcijan , zarzuca mu błąd przyjęcia ich doktryny , ale odseparowania się i wyboru własnego Dalaj Lamy .Dla jasności zacytujmy ich rozmowę :

- O jakim Dalaj Lamie ojciec mówi pytał Notowicz my mamy Syna Bożego do którego wznosimy modlitwy

- To nie o to chodzi odpowiedział lama — My także czcimy Jezusa , ale my nie uważamy go za Syna Bożego . W rzeczywistości Budda wcielił się w doskonale wybranego człowieka który sam siebie nazywał Jezus , ale my nazywaliśmy go Issa . Ale ja mówię o waszym ziemskim Dalaj Lamie , którego nazywacie Ojcem Kościoła . Issa był wielkim prorokiem . Większym od wszystkich innych , gdyż posiadał w sobie cząstkę Boga . My , buddyści , cierpimy z powodu tortur jakie zadali mu poganie .

Zaintrygowany Notowicz zaczął rozpytywać a jakieś manuskrypty , notatki . Okazało się że takowe były w każdym większym klasztorze w Nepalu . Po kilku tygodniach poszukiwań dotarł do jednego z najstarszych i nawiększych klasztorów Himis . Po załatwieniu niezbędnych formalności z audiencją u Lamy , Notowicz nie czekając na nic innego zadał pytanie o Jezusa . Na odpowiedź nie czekał długo.

Lama odpowiedział mu mniej więcej tymi słowy :

Imię Jezusa jest wielce szanowane wśród buddystów , ale szczegółowa prawda wiadoma jest tylko starszyźnie lamów , tym , którzy czytają stare księgi . Nasza biblioteka posiada ogromną liczbę rękopisów , a pomiędzy nimi są także opisy życia i nauczania Jezusa w Jerozolimie i Indiach . O jego działalności w swoim czasie krążyło dużo notatek w różnych językach , ale to wszystko jest przetłumaczone na język tybetański i znajduje się w bibliotece Lhassy . Kilkanaście kopii , może więcej , przekazano tutaj , ale niestety w żadnym wypadku nie mogę ich panu udostępnić . Takie jest polecenie Dalaj Lamy .

Rozgoryczony Notowicz opuścił klasztor z niczym . Już nazajutrz przekraczając jakiś jar upadł i złamał nogę . Zaniesiono go więc z powrotem do Himis .

Podczas sześciotygodniowej kuracji pod opieką mnichów , Notowicz zaprzyjaźnił się z przeorem na tyle , iż ten pozwolił mu nie tylko obejrzeć , ale i przetłumaczyć owe manuskrypty .

Dotyczyły one życia i działalności Jezusa . Z tych notatek , pisanych współcześnie Jezusowi powstała wielka księga . Z nagromadzonych pism wynikało , że któregoś dnia ,zjawił się w krainie Jainów dwunastoletni chłopak imieniem Jezus i spędził pod kierunkiem starych Jainów w Dżuggernaut , Radżegrika i Benares długie sześć lat . Stąd przeniósł się do Nepalu , do miasta Dżagannat , gdzie istniała potrzebna mu do dalszych studiów biblioteka dzieł w sanskrycie . Prowadził liczne dysputy z bramińskimi mędrcami usiłując przekonać ich o krzywdzących stosunkach społecznych , panujących w ich kraju .

Jak się okazuje kluczowe miejsca dla pobytu Jezusa w Indiach to również znana nam Ziemia Lodu – Ladakh w Tybecie-Tubądcie, leżąca na granicy Krainy Kasztrijów- czyli Kaszmiru, dawnego królestwa Kuszanów (Koszetyrsów), a kluczowe zapisy na ten temat tłumaczone są z języka PALI

Jak się okazuje kluczowe miejsca dla pobytu Jezusa w Indiach to również znana nam Ziemia Lodu – Ladakh w Tybecie-Tubądcie, leżąca na granicy Krainy Kasztrijów- czyli Kaszmiru, dawnego królestwa Kuszanów (Koszetyrsów), a kluczowe zapisy na ten temat tłumaczone są z języka PALI

Wbrew zakazom kontaktowania się z podle urodzonymi wajsiami i jeszcze gorszymi siudrami , Jezus coraz żarliwiej jął uczyć o Bogu , który nie uznaje różnic i jest jeden dla wszystkich , niezależnie od pochodzenia społecznego .

Stosunki społeczne panujące w Indiach oburzały Jezusa do głębi , Jako przybysz z zewnątrz patrzył na to wszystko innymi oczyma . Wziął więc obyczajem miejscowych mędrców , mosiężną miskę w dłonie i ruszył przed siebie wzdłuż rzeki Ganges . Nie zamierzał nikogo podburzać , chciał tylko krzepić ludzkie serca pogodą i życzliwością . Coraz więcej szło za nim uczniów . Nazywano go Issa Wędrowiec , gdyż szedł uparcie przed siebie nie pozwalając sobie na odpoczynek .

Pośród braminów rósł niepokój . Przygotowali zamach , ale uczniowie w porę uprzedzili Jezusa . Uszedł więc do Nepalu , do klasztoru buddyjskiego . Panująca tu atmosfera odpowiadała mu , gdyż znalazł tu spokój którego tak potrzebował . Spędził więc w klasztorze kolejne sześć lat . Gdy ukończył dwadzieścia sześć lat , postanowił wrócić do rodzinnego kraju . Wędrował najkrótszą znaną mu drogą , przez Afganistan i Persję . Którędy szedł , tam starał się nauczać , i wszędzie gdzie przeszedł robił sobie wrogów z kapłanów . Pomimo wszystkich ich podstępów , zamachów i czyhających zewsząd niebezpieczeństw Jezus powoli zbliżał się do Izraela , aż któregoś dnia znalazł się w rodzinnej Galilei . Ukończył wtedy 29 rok życia .

Po zapoznaniu się z treścią manuskryptów , oszołomiony Notowicz , mniemał najzupełniej słusznie że cały świat nauki chrześcijańskiej ucieszy się ogromnie . Pośpieszył więc do swego rodzinnego Kijowa , aby nazajutrz po przybyciu udać się do archimandryty Platona metropolity prawosławnego . Z dumą wręczył mu swoje rosyjskie tłumaczenie , przekonany o niezmiernej wartości tego dokumentu .

Po kilku dniach archimandryta Platon zwrócił mu rękopisy , potwierdził nadzwyczajną wartość zawartych w nich informacji , ale z całego serca poradził nie publikować ich .

Czasy są nieodpowiednie stwierdził Tego rodzaju nowinka może być bardzo niebezpieczna , zresztą ogłoszenie tego może panu poważnie zaszkodzić w karierze . Mogę natomiast rękopis od pana kupić. Proszę o podanie ceny .

Zawiedziony Notowicz milczał cierpliwie cały rok , czekając na poprawę aktualnej , ponoć nienajlepszej sytuacji prawosławia .

Po roku udał się do Rzymu , dopuszczono go jednak tylko przed oblicze rzeczoznawcy kardynała . Ten po przeczytaniu rękopisu odezwał się w te słowa :

Jakiż może być pożytek z opublikowania podobnej rozprawy ? Nikt nie potraktuje pana poważnie , a ponadto zrobi pan sobie wielu wrogów i to potężnych . Jeśli chodzi o pieniądze , to jestem gotów w zamian za rękopis pokryć wszystkie poniesione koszta , a także i zrekompensować stracony czas .

Oburzony Notowicz opuścił Rzym tego samego dnia . Chciał jeszcze spróbować szans w Paryżu , gdzie znał kardynała Rotelliego .

Kardynał Rotelli po zapoznaniu się z rękopisem , powtórzył słowo w słowo argumenty przytoczone przez archimandrytę Platona i kardynała w Rzymie . Stwierdził że publikacja może stać się przyczynkiem do ateistycznych rozruchów . Wobec powyższego Notowicz zdecydował się na przerzucenie całej akcji za środowiska duchowego , na środowisko świeckie . Udał się do znanego filozofa Jules Simona . Ten ogromnie się przejął sprawą , ale skierował Notowicza do wyższego autorytetu , a mianowicie do autora głośnej biografii Jezusa Ernesta Renana . Treść rękopisu niezmiernie poruszyła Renana , który nie podważał jego prawdziwości , a wręcz przeciwnie proponował odczytanie rękopisu na najbliższym spotkaniu Akademii Francuskiej . W pierwszym odruchu Notowicz wyraził zgodę , ale po całonocnym namyśle cofnął ją . Gdyby bowiem Renan z całą swoją sławą i renomą zreferował sprawę Akademii , to prawdziwy odkrywca pozostał by w cieniu . Notowicz postanowił więc sam opracować książkę w języku francuskim . Trwało to cały rok . W tym czasie zmarł profesor Renan . Wkrótce ukazała się książka Notowicza La Vie Inconnue De Jesus Christ (Nieznane życie Jezusa Chrystusa) .

Był rok 1894 . Ku zdumieniu autora i wydawcy cały nakład książki znikł nazajutrz z półek księgarskich . Czyżby książka miała aż takie powodzenie ?

Wydrukowano pośpiesznie kolejny nakład , ale i on następnego dnia znikł z półek . Powtórzono jeden po drugim siedem nakładów . Wszystkie ginęły . Najdziwniejszą stroną tej całej historii jest fakt, że we Francji z siedmiu nakładów nie przechował się do dziś ani jeden egzemplarz . Po prostu wyparowały , znikły … Dwa francuskie egzemplarze są do dziś w British Museum ( jeden egzemplarz wydania czwartego i jeden siódmego ) . Żadnej reakcji w prasie , żadnej recenzjii . Nawet biografowie Chrystusa nie wymieniają tej książki w swoich bibliografiach . Religioznawcze katalogi milczą . Tak jakby ta książka nigdy nie zaistniała .

Notowicz za namową przyjaciół wyprowadza się do Nowego Jorku .

W tym czasie niejaki R.Giovanni zdołał wydać książkę Notowicza w Lizbonie . Ale i tu cały nakład w cudowny sposób znika z półek . Oczywiście bez echa …

W Nowym Jorku Notowicz publikuje książkę pod tytułem Unknown Life of Jesus Christ(1895 r.) W związku z szybkim znikaniem tytułu z półek nakład wznowiono jednocześnie w Chicago i Londynie (1895 r.) . Jednak jak i w poprzednich wypadkach książka znikała z półek i nie pozostawiała po sobie żadnych śladów w prasie i opinii społecznej . Kolejnych wznowień już nie było , autor zakończył życie .

Tak było do roku 1907 , kiedy to Towarzystwo Teozoficzne (udział sekty teozoficznej w tej sprawie może być co najmniej podejrzany, ze względu na to, iż nikomu tak jak im nie mogło zależeć na takim odkryciu — wszak oni łączą chrześcijaństwo z buddyzmem — przyp. Mariusz Agnosiewicz.) w Chicago przypomniało sobie o niej i z przydługim wstępem o psychizmie książkę wydało . Niestety tego wydania także nie można dziś dostać . Po długich poszukiwaniach udało mi się znaleźć jeden , mocno zniszczony egzemplarz .

Edyta Notowicz przeżyła Auszwitz (foto 1996, Norwegia) tu z członkiem ruchu oporu Odd Olsenem (mąż?), który brał udział w sabotażu na Linię Thamsavn podczas II Wojny Światowej. Rodzina Notowiczów ma swoje Polskie ale też i Żydowskie korzenie. Jest związana ze wschodnią Polską: Lwowem , Rzeszowem i Kolbuszową.

Edyta Notowicz przeżyła Auszwitz (foto 1996, Norwegia) tu z członkiem ruchu oporu Odd Olsenem (mąż?), który brał udział w sabotażu na Linię Thamsavn podczas II Wojny Światowej. Rodzina Notowiczów ma swoje Polskie ale też i Żydowskie korzenie. Jest związana ze wschodnią Polską: Lwowem , Rzeszowem i Kolbuszową.

Φ

Nicolas Notovitch

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nicolas Notovitch (1858-?) was a Russian aristocrat, Cossack officer,[1] spy[2][3] and journalist known for his contention that during the years of Jesus Christ’s life missing from the Bible, he followed travelling merchants abroad into India and the Hemis Monastery in Ladakh,[4][5][6][7][8] India, where he studied Buddhism.

Life of Saint Issa

Notovitch claimed that, at the lamasery or monastery of Hemis, he learned of the „Life of Saint Issa, Best of the Sons of Men.” His story, with the text of the „Life,” was published in French in 1894 as La vie inconnue de Jesus Christ. It was translated into English,[9] German, Spanish, and Italian.

Notovitch’s account of his discovery of the work is that he had been laid up with a broken leg at the monastery of Hemis. There he prevailed upon the chief lama, who had told him of the existence of the work, to read to him, through an interpreter, the somewhat detached verses of the Tibetan version of the „Life of Issa,” which was said to have been translated from the Pali. Notovitch says that he himself afterward grouped the verses „in accordance with the requirements of the narrative.” As published by Notovitch, the work consists of 244 short paragraphs, arranged in fourteen chapters.

The otherwise undocumented name „Issa” resembles the Arabic name Isa (عيسى), used in the Koran to refer to Jesus and the Sanskrit „īśa”, the Lord.

The „Life of Issa” begins with an account of Israel in Egypt, its deliverance by Moses, its neglect of religion, and its conquest by the Romans. Then follows an account of the Incarnation. At the age of thirteen the divine youth, rather than take a wife, leaves his home to wander with a caravan of merchants to India (Sindh), to study the laws of the great Buddhas.

Issa is welcomed by the Jains, but leaves them to spend time among the Buddhists, and spends six years among them, learning Pali and mastering their religious texts. Issa spent six years studying and teaching at Jaganath, Rajagriha, and other holy cities. He becomes embroiled in a conflict with the Kshatriyas (warrior class), and the Brahmins (priestly class) for teaching the holy scriptures to the lower castes (Sudras and Vaisyas, laborers and farmers). The Brahmins said that the Vaisyas were authorized to hear the ‚Vedas’ read only during festivals and especially not to be read to the Sudras at all who are not even allowed to look at them. Rather than abide by their injunction, Issa preaches against the Brahmins and Kshatriyas, and aware of his denunciations, they plot his death. Warned by the Sudras, Issa leaves Jaganath and travels to the foothills of the Himalayas in Southern Nepal (birthplace of the Buddha).

At twenty-nine, Issa returns to his own country and begins to preach. He visits Jerusalem, where Pilate is apprehensive about him. The Jewish leaders, however, are also apprehensive about his teachings yet he continues his work for three years. He is finally arrested and put to death for blasphemy, for claiming to be the son of God. His followers are persecuted, but his disciples carry his message to the world.

In the Notovich translation, the section regarding Pontius Pilate is of particular note; in this version of the events around the death of Jesus, the Sanhedrin go to Pilate and argue to save the life of Jesus, and they are the ones who ‚wash their hands’ of his death, instead of the Roman Pilate. Another point is the role of women that appear to be more free than what most historians think.

Controversy

While Edgar Goodspeed does find evidence that Notovitch was in Ladakh at the time he claims, he judges the essential part of his tale to be a hoax.

Some light was thrown upon the matter by a communication sent to The Nineteenth Century in June 1895 by Professor J. Archibald Douglas of Agra, who was at that time a guest in the Himis monastery, enjoying the hospitality of that very chief lama who was supposed to have imparted the Unknown Life to Notovitch. Douglas found the animal life in the Sind Valley much less picturesque than Notovitch had described, and no memory of any foreigner with a broken leg lingered at Leh or Himis. But Douglas’ inquiries did at length elicit the report that a Russian gentleman named Notovitch had recently been treated for the toothache by the medical officer of Leh hospital. To that extent Notovitch’s narrative seems to have been on firm ground.

But no further. The chief lama indignantly repudiated the statements ascribed to him by Notovitch, and declared that no traveler with a broken leg had ever been nursed at the monastery. He stated with emphasis that no such work as the „Life of Issa” was known in Tibet, and that the statement that he had imparted such a record to a traveler was a pure invention. When Notovitch’s book was read to him he exclaimed with indignation, „Lies, lies, lies, nothing but lies!” The chief lama had not received from Notovitch the presents Notovitch reported having given him–the watch, the alarm clock, and the thermometer. He did not even know what a thermometer was. In short the chief lama made a clean sweep of the representations of Notovitch, and with the aid of Douglas effected what Muller described as his „annihilation.”.[10]

The story of his visit to Hemis seems to be taken from H.P. Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled.[11] In the original, the traveler with the broken leg was taken in at Mount Athos in Greece and found the text of Celsus’ True Doctrine in the monastery library. But in fact proof was found that Notovitch was in Leh and Hemis. A German dentist residing there had treated him, extracting one of his teeth.[citation needed] There is the written record in his diary which is shown in the book of Holger Kersten.

The idea that Jesus was in India was also inspired by a statement in Isis that he went to the foothills of the Himalayas.[12]

Bart D. Ehrman says that „Today there is not a single recognized scholar on the planet who has any doubts about the matter. The entire story was invented by Notovitch, who earned a good deal of money and a substantial amount of notoriety for his hoax.”[13]

Other authors on the life of Jesus in India

While Notovitch is the first author known to claim Jesus traveled to India, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (died 1908), who proclaimed himself the awaited Messiah, wrote a more detailed account of Jesus’s time in South Asia. Unlike Notovitch, he claimed that Jesus had traveled towards India post-crucifixion in search of the lost tribes of Israel and there he died a natural death. Ghulam Ahmad founded the Ahmadiyya sect. Others claim to have seen the same manuscripts.

Many other authors have taken this information and incorporated it into their own works. For example, in her book „The Lost Years of Jesus: Documentary Evidence of Jesus’ 17-Year Journey to the East”, Elizabeth Clare Prophet asserts that Buddhist manuscripts provide evidence that Jesus traveled to India, Nepal, Ladakh and Tibet.[14]

During his stay in Ladakh, Notovitch collected several Mani stones on which were engraved sacred Tibetan words which were later donated to the Trocadero Museum in Paris. Also in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris there is a piece of Kashmiri fabric registered under his name. The night between the 3 and 4 November 1887 Notovitch suffered severe toothache, for which he sought the assistance of a German missionary, Dr. Karl Rudolph Marx, who had studied medicine in Edinburgh, and who had been working as the director of the Leh hospital since 1866. Marx belonged to the Moravian brothers. The diary of Dr. Marx correctly reports having treated Notovitch for his toothache.

In 1893, Notovitch’s work was first presented at an international forum in Chicago by Shri Virchand Gandhi, an important delegate to the First Parliament of the World’s Religions. Shri Virchand Gandhi is credited for originally translating and publishing the same work in English in 1894 from an ancient manuscript found in Tibet. This version is available online.

One of the skeptics who personally investigated Notovich’s claim was Swami Abhedananda, who journeyed to the monastery determined to either find a copy of the Himis manuscript or to expose it as a fraud. His book of travels, entitled Kashmir O Tibetti, tells of a visit to the Hemis gompa and includes a Bengali translation of two hundred twenty-four verses essentially the same as the Notovitch text,[15] corroborating the existence of the documents.

In 1925, the Russian philosopher Nicholas Roerich also journeyed to the monastery. He apparently saw the same documents as Notovitch and Abhedananda.

There is a documentary and a book on this subject, by Richard Bock, who seems to believe Notovitch’s claims (book and film 1976-77, DVD released 2007).[16]

An extended publication regarding the years spent by Jesus in India, with extremely detailed historical accounts and pictures, is contained in the best selling book „Jesus lived in India” by Holger Kersten.

Other works

Notovitch published a book in Russian and French, pleading for Russia’s entry into the Triple Entente with France and England. It is entitled in French: La Russie et l’alliance anglaise: étude historique et politique, and was published in 1906. He also wrote biographies of Tsar Nicolas II and Alexander III. (Sources: worldcat.org, books.google.com.) He had also written „Mariage Ideal”; A Travers L’Inde” „La Femme à Travers le Monde” He might have had the dubious honour of being quoted by Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf, but it has not yet been seen in any of the copies/versions widely available.

Further reading

H. Louis Fader, The Issa Tale That Will Not Die: Nicholas Notovich and His Fraudulent Gospel (University Press of America, 2003). ISBN 978-0-7618-2657-6

Angelo Paratico „The Karma Killers” New York, 2009. This is a novel based on Notovitch stoy, set in modern times with flashbacks to the time of Jesus and to WWII. Most of it is based in Hong Kong and Tibet. It was first printed in Italy under the title Gli Assassini del Karma, Rome 2003.

References

- ^ Theosophie, „Meister K.H.” und die Dalip-Singh-Verschwörung, 2. Teil, Kommentar http://www.anthroposophy.com/anthro/blava2.html

- ^ India Office Records: Mss Eur E243/23 (Cross)

- ^ Public Record Office: FO 78/3998

- ^ The unknown life of Jesus Christ by Nickolai Notovich (1894)

- ^ The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ by Nicholas; Translated from the French By Virchand R. Gandhi; Revised By G. L. Chistie Notovich and Black/white Illus (1907)

- ^ The unknown life of Jesus Christ by Nicolas Notovich (1974)

- ^ The Unknown Life of Jesus: The Original Text of Nicolas Notovich’s 1887 Discovery by Nicolas Notovich, J.H Connelly, and L Landsberg (2004)

- ^ The Vedic Prophecies: A New Look into the Future by Stephen Knapp (1998) p.12

- ^ Notovitch, Nicolas (1890). The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ.

- ^ Goodspeed, Edgar J. (1956). Famous Biblical Hoaxes or, Modern Apocrypha. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.. See also [1]

- ^ H.P. Blavatsky. Isis Unveiled, Vol. II, part 2, ch. 1, page 52, footnote** http://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/isis/iu2-01.htm

- ^ H.P. Blavatsky. Isis Unveiled, Vol. II, part 2, ch. 3, page 164 http://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/isis/iu2-03.htm

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (February 2011). „8. Forgeries, Lies, Deceptions, and the Writings of the New Testament. Modern Forgeries, Lies, and Deceptions” (EPUB). Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. (First Edition. EPub Edition. ed.). New York: HarperCollins e-books. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ^ Prophet, Elizabeth Clare. The Lost Years of Jesus: Documentary Evidence of Jesus’ 17-Year Journey to the East. p. 468. ISBN 0-916766-87-X.

- ^ Ramakrishna Vedanta Math website

- ^ http://www.amazon.com/Lost-Years-Jesus-William-Marshall/dp/B000TAPCCC

Φ

Нотович, Николай Александрович

Материал из Википедии — свободной энциклопедии

Перейти к: навигация, поиск

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с такой фамилией, см. Нотович.

Николай Александрович Нотович

Николай (Шулим) Александрович Нотович (1858 — ?) — российский разведчик, писатель, журналист, дворянин и казак-офицер. Известен написанной по-французски книгой «Неизвестная жизнь Иисуса Христа» (более известной как «Тибетское Евангелие»), якобы содержащей ранние проповеди Иисуса и предполагающей, что Иисус от 12 до 30 лет жил в Индии.

Биография

Его родители были евреями, но он в молодости выкрестился в православие[1][2]. В 1910-х гг. в Петербурге Нотович участвовал в создании акционерного «Товарищества периодических изданий», был директором-распорядителем акционерного общества графических искусств «Дело», редактором-издателем еженедельника «Финансовое обозрение» (1910–17), газеты «Вечерний курьер» (1914) и «Петербургский курьер» (1914–15), издавал еженедельный литературно-художественный журнал «Жемчужина» (1914–15) и газету «Голос» (1915–16), редактировал журнал «Иллюстрированный петербургский курьер» (1914).

Ссылки

- Николай Нотович: Неизвестная жизнь Иисуса Христа

Библиография

- Патриотизм. Стихотворения. СПб., 1880

- Жизнеописание славного русского героя и полководца генерал-адъютанта генерала от инфантерии Михаила Дмитриевича Скобелева. Спб., 1882

- Кветта и военная железная дорога через перевалы Болан и Гернаи. Тифлис, 1888

- Где дорога в Индию? М., 1889

- Правда об евреях. М, 1889

- Европа накануне войны. М., 1890

- Неизвестная жизнь Иисуса Христа. Киев, 1904

- Россия и Англия. Ист.-полит. этюд. СПб., 1907.

- Проект организации Министерства торговли и промышленности (основы и соображения). Спб., 1907

- Россия и Англия. Историко-политический этюд. Спб, 1909

- Наш торговый флот, его экономическое и политическое значение. Н. А. Нотович, учредитель пароходного и страхового общества „Полярная звезда”. СПб, 1912.

- Nicolas Notovitch. L’Europe et l’Égypte. P. Ollendorff, 1898.

- Nicolas Notovitch. Livre d’or à la mémoire d’Alexandre III. En vente au siège du Comité patriotique du Livre d’or, 1895.

- Nicolas Notovitch. L’empereur Nicolas II et la politique russe. P. Ollendorff, 1895.

- Nicolas Notovitch. La pacification de l’Europe et Nicolas II. Paul Ollendorff, 1899.

- Nicolas Notovitch. Le tsar, son armée et sa flotte: Ouvrage orné de 80 illustrations. J. Rouam et cie, 1893.

- La Russie Et L’Alliance Anglaise: Étude Historique Et Politique.

Примечания

- ↑ Фида М. Хасснайн. В поисках исторического Иисуса. М., 2006. Глава 3

- ↑ Дудаков С. Ю. Этюды любви и ненависти. М., 2003. С. 277

The Lost Years of Jesus:

The Life of Saint Issa

Translation by Notovitch

Jesus approaching Ladakh as a youth

Oil painting by J. Michael Spooner

The Best of the Sons of Men

- Ancient scrolls reveal that Jesus spent seventeen years in India and Tibet

- From age thirteen to age twenty-nine, he was both a student and teacher of Buddhist and Hindu holy men

- The story of his journey from Jerusalem to Benares was recorded by Brahman historians

- Today they still know him and love him as St. Issa. Their ‚buddha’

In 1894 Nicolas Notovitch published a book called The Unknown Life of Christ. He was a Russian doctor who journeyed extensively throughout Afghanistan, India, and Tibet. Notovitch journeyed through the lovely passes of Bolan, over the Punjab, down into the arid rocky land of Ladak, and into the majestic Vale of Kashmir of the Himalayas. During one of his jouneys he was visiting Leh, the capital of Ladak, near where the buddhist convent Himis is. He had an accident that resulted in his leg being broken. This gave him the unscheduled opportunity to stay awhile at the Himis convent.

Notovitch learned, while he was there, that there existed ancient records of the life of Jesus Christ. In the course of his visit at the great convent, he located a Tibetan translation of the legend and carefully noted in his carnet de voyage over two hundred verses from the curious document known as „The Life of St. Issa.”

He was shown two large yellowed volumes containing the biography of St. Issa. Notovitch enlisted a member of his party to translate the Tibetan volumes while he carefully noted each verse in the back pages of his journal.

When he returned to the western world there was much controversy as to the authenticity of the document. He was accused of creating a hoax and was ridiculed as an imposter. In his defense he encouraged a scientific expedition to prove the original tibetan documents existed.

One of his skeptics was Swami Abhedananda. Abhedananda journeyed into the arctic region of the Himalayas, determined to find a copy of the Himis manuscript or to expose the fraud. His book of travels, entitled Kashmir O Tibetti, tells of a visit to the Himis gonpa and includes a Bengali translation of two hundred twenty-four verses essentially the same as the Notovitch text. Abhedananda was thereby convinced of the authenticity of the Issa legend.

Map of Jesus’s eastern travels

Source: Summit University Press

In 1925, another Russian named Nicholas Roerich arrived at Himis. Roerich, was a philosopher and a distinguished scientist. He apparently saw the same documents as Notovitch and Abhedananda. And he recorded in his own travel diary the same legend of St. Issa. Speaking of Issa, Roerich quotes legends which have the estimated antiquity of many centuries.

… He passed his time in several ancient cities of India such as Benares. All loved him because Issa dwelt in peace with Vaishas and Shudras whom he instructed and helped. But the Brahmins and Kshatriyas told him that Brahma forbade those to approach who were created out of his womb and feet. The Vaishas were allowed to listen to the Vedas only on holidays and the Shudras were forbidden not only to be present at the reading of the Vedas, but could not even look at them.

Issa said that man had filled the temples with his abominations. In order to pay homage to metals and stones, man sacrificed his fellows in whom dwells a spark of the Supreme Spirit. Man demeans those who labor by the sweat of their brows, in order to gain the good will of the sluggard who sits at the lavishly set board. But they who deprive their brothers of the common blessing shall be themselves stripped of it.

Vaishas and Shudras were struck with astonishment and asked what they could perform. Issa bade them „Worship not the idols. Do not consider yourself first. Do not humiliate your neighbor. Help the poor. Sustain the feeble. Do evil to no one. Do not covet that which you do not possess and which is possessed by others.”

Many, learning of such words, decided to kill Issa. But Issa, forewarned, departed from this place by night.

Afterward, Issa went into Nepal and into the Himalayan mountains ….

„Well, perform for us a miracle,” demanded the servitors of the Temple. Then Issa replied to them: „Miracles made their appearance from the very day when the world was created. He who cannot behold them is deprived of the greatest gift of life. But woe to you, enemies of men, woe unto you, if you await that He should attest his power by miracle.”

Issa taught that men should not strive to behold the Eternal Spirit with one’s own eyes but to feel it with the heart, and to become a pure and worthy soul….

„Not only shall you not make human offerings, but you must not slaughter animals, because all is given for the use of man. Do not steal the goods of others, because that would be usurpation from your near one. Do not cheat, that you may in turn not be cheated ….

„Beware, ye, who divert men from the true path and who fill the people with superstitions and prejudices, who blind the vision of the seeing ones, and who preach subservience to material things. „…

Then Pilate, ruler of Jerusalem, gave orders to lay hands upon the preacher Issa and to deliver him to the judges, without however, arousing the displeasure of the people.

But Issa taught: „Do not seek straight paths in darkness, possessed by fear. But gather force and support each other. He who supports his neighbor strengthens himself

„I tried to revive the laws of Moses in the hearts of the people. And I say unto you that you do not understand their true meaning because they do not teach revenge but forgiveness. But the meaning of these laws is distorted.”

Then the ruler sent to Issa his disguised servants that they should watch his actions and report to him about his words to the people.

„Thou just man, „said the disguised servant of the ruler of Jerusalem approaching Issa, „Teach us, should we fulfill the will of Caesar or await the approaching deliverance?”

But Issa, recognizing the disguised servants, said, „I did not foretell unto you that you would be delivered from Caesar; but I said that the soul which was immersed in sin would be delivered from sin.”

At this time, an old woman approached the crowd, but was pushed back. Then Issa said, „Reverence Woman, mother of the universe,’ in her lies the truth of creation. She is the foundation of all that is good and beautiful. She is the source of life and death. Upon her depends the existence of man, because she is the sustenance of his labors. She gives birth to you in travail, she watches over your growth. Bless her. Honor her. Defend her. Love your wives and honor them, because tomorrow they shall be mothers, and later-progenitors of a whole race. Their love ennobles man, soothes the embittered heart and tames the beast. Wife and mother-they are the adornments of the universe.”

„As light divides itself from darkness, so does woman possess the gift to divide in man good intent from the thought of evil. Your best thoughts must belong to woman. Gather from them your moral strength, which you must possess to sustain your near ones. Do not humiliate her, for therein you will humiliate yourselves. And all which you will do to mother, to wife, to widow or to another woman in sorrow-that shall you also do for the Spirit.”

So taught Issa; but the ruler Pilate ordered one of his servants to make accusation against him.

Said Issa: „Not far hence is the time when by the Highest Will the people will become purified and united into one family.”

And then turning to the ruler, he said, „Why demean thy dignity and teach thy subordinates to live in deceit when even without this thou couldst also have had the means of accusing an innocent one?”

From another version of the legend, Roerich quotes fragments of thought and evidence of the miraculous.

Near Lhasa was a temple of teaching with a wealth of manuscripts. Jesus was to acquaint himself with them. Meng-ste, a great sage of all the East, was in this temple.

Finally Jesus reached a mountain pass and in the chief city of Ladak, Leh, he was joyously accepted by monks and people of the lower class …. And Jesus taught in the monasteries and in the bazaars (the market places); wherever the simple people gathered–there he taught.

Not far from this place lived a woman whose son had died and she brought him to Jesus. And in the presence of a multitude, Jesus laid his hand on the child, and the child rose healed. And many brought their children and Jesus laid his hands upon them, healing them.

Among the Ladakis, Jesus passed many days, teaching them. And they loved him and when the time of his departure came they sorrowed as children.

Click here to read ‚The Life of Saint Issa’ Translation by Notovitch

Chapters

Introduction | I-V | VI-VIII | IX-XI | XII-XIV

Jeszcze o dziele Notowicza (dogłębniej – tylko dla miłośników tego tematu)

Nicolas Notovitch

In 1894, the Russian war correspondent Nicolas Notovitch published a book entitled „La vie inconnue de Jésus-Christ”, later translated and published as „The Life of the Holy Issa”. He claimed to have made a sensational manuscript find in a Lamaist monastery in Tibet. The monastery of Himis still exists, near Leh, the capital of Ladakh at the border between Tibet and India. Notovitch claimed to have been taken there after breaking his leg in an accident, and during his recovery to have discovered that the monks worshipped a prophet named Issa. When they read their scrolls about this person to him, he realized that Issa was none other than Jesus.

The scrolls told that in his youth, Jesus had travelled to India and Tibet, years before he began his work in Palestine. He there met with Jainists, Brahmins and Buddhists, learned Pali and studied the holy scriptures of Buddhism. Notovitch wrote down the text as it was read by the abbot and translated for him by an interpreter. According to Notovitch, the Tibetan scrolls were translations of Pali documents which the abbot claiimed were still kept at Lhasa. (In fact, Pali is the language of southern Buddhism and has never been used in Tibet. Most Tibetan translations are from Sanskrit.)

Notovitch’s book „The Life of the Holy Issa” was published in France, Britain and America. But criticism hit hard. None less than Max Müller, the foremost expert on Indian literature in the Western world, pulverized the hoax in a magazine article, pointing to numerous errors and inconsistencies. Further, an English lady travelling in those parts of the world went to the Himis monastery and asked around. She was told that no Russian had visited the monastery for many years and nobody had been treated for any leg injury there, and that they never heard of an „Issa”.

The final judgement on Notovitch’s hoax came two years later from professor Archibald Douglas in Agra. He also went to the monastery and read aloud from Notovitch’s book to the abbot, who was very surprised at the account of what he himself was supposed to have said to Notovitch a few years earlier. Douglas published his interview with the abbot, who claimed to have been abbot there for 15 years and denied every syllable of Notovitch’s story. He also remarked that he could not think of a punishment suitable for scum who invented such lies as Notovitch. The interview was witnessed and signed by Douglas, the abbot and the interpreter, and officially sealed by the abbot.

Notovitch tried for some time to defend his story with various dodges, but finally gave up and returned to being a war correspondent. Unlike most hoaxers, he had no ideological motives for the hoax, just a desire to create a sensation. His thin story would probably not have received much attention at all if it had not been published at the peak of the 19th century Indian romanticism, just after Queen Victoria had been crowned Empress of India.

It’s still going on…

With this, the case should have been closed. But successful lies have a tendency to return. Notovitch’s book was printed again in 1926 by an American publisher who hoped (not without justification) that the debunking of the hoax had been forgotten. Even more, the story has inspired other hoaxers to fantazise about Jesus travelling to the mysterious East. Probably neither „The Gospel of the Holy Twelve” or „The Aquarian Gospel” would have existed without Notovitch’s ideas. Others with similar fantasies are the half-islamic Ahmadiyya sect who believe that Jesus survived the crucifixion and died of old age at Srinagar where he is also said to have been buried. To support this, their founder Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad quoted another hoax, the „Barnabas gospel”. Modern Ahmadiyya books quote both the „Essene epistle” and the „Life of the Holy Issa” as if they were authentic documents about Jesus.

The story of Notovitch demonstrates the incredible survival power of lies that capture the popular imagination, and the powerlesness of science to eradicate belief in even the most absurd hoaxes. Conclusive proof is apparently not enough. „The world wants to be deceived.”

Some articles on Notovitch, The Unknown Life of Christ.

The Nineteenth Century, 36 (July-December 1894) pp. 515-522

THE ALLEGED SOJOURN OF CHRIST IN INDIA 1

Aeneas Sylvius, afterwards Pope Pius the Second, 1458-64, when on a visit to England, was anxious to see with his own eyes the barnacle geese that were reported to grow on trees, and, being supposed to be vegetable rather than animal, were allowed to be eaten during Lent. He went as far as Scotland to see them, but when arrived there he was told that he must go further, to the Orchades, if he wished to see these miraculous geese. He seemed rather provoked at this, and, complaining that miracles would always flee further and further, he gave up his goose chase (didicimus miracula semper remotius fugere).

Since his time, the number of countries in which miracles and mysteries could find a safe hiding-place has been much reduced. If there were a single barnacle goose left in the Orchades, i.e. the Orkney Islands, tourists would by this time have given a good account of it. There are few countries left now beyond the reach of steamers or railways, and if there is a spot never trodden by a European foot, that is the very spot which is sure to be fixed upon by some adventurous members of the Alpine Club for their next expedition. Even Central Asia and Central Africa are no longer safe, and, hence, no doubt, the great charm which attaches to a country like Tibet, now almost the only country some parts of which are still closed against European explorers. It was in Tibet, therefore, that Madame Blavatsky met her Mahâtmas, who initiated her in the mysteries of Esoteric Buddhism. Mr. Sinnet claims to have followed in her footsteps, but has never described his or her route. Of course, if Madame Blavatsky and Mr. Sinnet had only told us by what passes they entered Tibet from India, at what stations they halted, and in what language they communicated with the Mahâtmas, it would not be courteous to ask any further questions. That there are Mahâtmas in India and Tibet no one would venture to deny. The only doubt is whether these real Mahâtmas know, or profess to know, anything beyond what they can, and what we can, learn from their sacred literature. If so, they have only to give the authorities to which they appeal for their esoteric knowledge, and we shall know at |516 once whether they are right or wrong. Their Sacred Canon is accessible to us as it is to them, and we could, therefore, very easily come to an understanding with them as to what they mean by Esoteric Buddhism. Their Sacred Canon exists in Sanskrit, in Chinese, and in Tibetan, and no Sacred Canon is so large and has at the same time been so minutely catalogued as that of the Buddhists in India, China, or Tibet.

But though certain portions of Tibet, and particularly the capital (Lassa), are still inaccessible, at least to English travellers from India, other portions of it, and the countries between it and India, are becoming more and more frequented by adventurous tourists. It would therefore hardly be safe to appeal any longer to unknown Mahâtmas, or to the monks of Tibetan monasteries, for wild statements about Buddhism, esoteric or otherwise, for a letter addressed to these monasteries, or to English officials in the neighbourhood, would at once bring every information that could be desired. „Where detection was so easy, it is almost impossible to believe that a Russian traveller, M. Notovitch, who has lately published a ‚Life of Christ’ dictated to him by Buddhist priests in the Himis Monastery, near Leh, in Ladakh, should, as his critics maintain, have invented not only the whole of this Vie inconnue de Jésus-Christ, but the whole of his journey to Ladakh. It is no doubt unfortunate that M. Notovitch lost the photographs which he took on the way, but such a thing may happen, and if an author declares that he has travelled from Kashmir to Ladakh one can hardly summon courage to doubt his word. It is certainly strange that letters should have been received not only from missionaries, but lately from English officers also passing through Leh, who, after making careful inquiries on the spot, declare that no Russian gentleman of the name of Notovitch ever passed through Leh, and that no traveller with a broken leg was ever nursed in the monastery of Himis. But M. Notovitch may have travelled in disguise, and he will no doubt be able to prove through his publisher, M. Paul Ollendorf, how both the Moravian missionaries and the English officers were misinformed by the Buddhist priests of the monastery of Leh. The monastery of Himis has often been visited, and there is a very full description of it in the works of the brothers Schlagintweit on Tibet.

But, taking it for granted that M. Notovitch is a gentleman and not a liar, we cannot help thinking that the Buddhist monks of Ladakh and Tibet must be wags, who enjoy mystifying inquisitive travellers, and that M. Notovitch fell far too easy a victim to their jokes. Possibly, the same excuse may apply to Madame Blavatsky, who was fully convinced that her friends, the Mahâtmas of Tibet, sent her letters to Calcutta, not by post, but through the air, letters which she showed to her friends, and which were written, not on Mahâtmic paper and with Mahâtmic ink, but on English paper and |517 with English ink. Be that as it may, M. Notovitch is not the first traveller in the East to whom Brâhmans or Buddhists have supplied, for a consideration, the information and even the manuscripts which they were in search of. Wilford’s case ought to have served as a warning, but we know it did not serve as a warning to M. Jacolliot when he published his Bible dans l’Inde from Sanskrit originals, supplied to him by learned Pandits at Chandranagor. Madame Blavatsky, if I remember rightly, never even pretended to have received Tibetan manuscripts, or, if she had, neither she nor Mr. Sinnet have ever seen fit to publish either the text or an English translation of these treasures.

But M. Notovitch, though he did not bring the manuscripts home, at all events saw them, and not pretending to a knowledge of Tibetan, had the Tibetan text translated by an interpreter, and has published seventy pages of it in French in his Vie inconnue de Jésus-Christ. He was evidently prepared for the discovery of a Life of Christ among the Buddhists. Similarities between Christianity and Buddhism have frequently been pointed out of late, and the idea that Christ was influenced by Buddhist doctrines has more than once been put forward by popular writers. The difficulty has hitherto been to discover any real historical channel through which Buddhism could have reached Palestine at the time of Christ. M. Notovitch thinks that the manuscript which he found at Himis explains the matter in the simplest way. There is no doubt, as he says, a gap in the life of Christ, say from his fifteenth to his twenty-ninth year. During that very time the new Life found in Tibet asserts that Christ was in India, that he studied Sanskrit and Pâli, that he read the Vedas and the Buddhist Canon, and then returned through Persia to Palestine to preach the Gospel. If we understand M. Notovitch rightly, this Life of Christ was taken down from the mouths of some Jewish merchants who came to India immediately after the Crucifixion (p. 237). It was written down in Pâli, the sacred language of Southern Buddhism; the scrolls were afterwards brought from India to Nepaul and Makhada (quaere Magadha) about 200 a.d. (p. 236), and from Nepaul to Tibet, and are at present carefully preserved at Lassa. Tibetan translations of the Pâli text are found, he says, in various Buddhist monasteries, and, among the rest, at Himis. It is these Tibetan manuscripts which were translated at Himis for M. Notovitch while he was laid up in the monastery with a broken leg, and it is from these manuscripts that he has taken his new Life of Jesus Christ and published it in French, with an account of his travels. This volume, which has already passed through several editions in France, is soon to be translated into English.

There is a certain plausibility about all this. The language of Magadha, and of Southern Buddhism in general, was certainly Pâli, and Buddhism reached Tibet through Nepaul. But M. Notovitch ought to |518 have been somewhat startled and a little more sceptical when he was told that the Jewish merchants who arrived in India immediately after the Crucifixion knew not only what had happened to Christ in Palestine, but also what had happened to Jesus, or Issa, while he spent fifteen years of his life among the Brâhmans and Buddhists in India, learning Sanskrit and Pâli, and studying the Vedas and the Tripitaka. With all their cleverness the Buddhist monks would have found it hard to answer the question, how these Jewish merchants met the very people who had known Issa as a casual student of Sanskrit and Pâli in India —-for India is a large term—-and still more, how those who had known Issa as a simple student in India, saw at once that he was the same person who had been put to death under Pontius Pilate. Even his name was not quite the same. His name in India is said to have been Issa, very like the Arabic name Isâ’l Masîh, Jesus, the Messiah, while, strange to say, the name of Pontius Pilate seems to have remained unchanged in its passage from Hebrew to Pâli, and from Pâli to Tibetan. We must remember that part of Tibet was converted to Mohammedanism. So much for the difficulty as to the first composition of the Life of Issa in Pâli, the joint work of Jewish merchants and the personal friends of Christ in India, whether in Sind or at Benares. Still greater, however, is the difficulty of the Tibetan translation of that Life having been preserved for so many centuries without ever being mentioned. If M. Notovitch had been better acquainted with the Buddhist literature of Tibet and China, he would never have allowed his Buddhist hosts to tell him that this Life of Jesus was -well known in Tibetan literature, though read by the learned only. We possess excellent catalogues of manuscripts and books of the Buddhists in Tibet and in China. A complete catalogue of the Tripitaka or the Buddhist Canon in Chinese has been translated into English by a pupil of mine, the Rev. Bunyiu Nanjio, M.A., and published by the Clarendon Press in 1883. It contains no less than 1,662 entries. The Tibetan Catalogue is likewise a most wonderful performance, and has been published in the Asiatic Researches, vol. xx., by Csoma Körösi, the famous Hungarian traveller, who spent years in the monasteries of Tibet and became an excellent Tibetan scholar. It has lately been republished by M. Féer in the Annales du Musée Guimet. This Catalogue is not confined to what we should call sacred or canonical books, it contains everything that was considered old and classical in Tibetan literature. There are two collections, the Kandjur and the Tandjur. The Kandjur consists of 108 large volumes, arranged in seven divisions:

1. Dulva, discipline (Vinaya).

2. Sherch’hin, wisdom (Pragnâpâramitâ).

3. P’hal-ch’hen, the garland of Buddhas (Buddha-avatansaka).

4. Kon-tségs, mountain of treasures (Ratnakűta).

5. Mdo, or Sűtras, aphorisms (Sűtrânta). |519

6. Myang-Hdas, or final emancipation (Nirvâna).

7. Gryut, Tantra or mysticism (Tantra).

‚The Tandjur consists of 225 volumes, and while the Kandjur is supposed to contain the Word of Buddha, the Tandjur contains many books on grammar, philosophy, &c, which, though recognised as part of the Canon, are in no sense sacred.

In the Tandjur, therefore, if not in the Kandjur, the story of Issa ought to have its place, and if M. Notovitch had asked his Tibetan friends to give him at least a reference to that part of the Catalogue where this story might be found, he would at once have discovered that they were trying to dupe him. Two things in their account are impossible, or next to impossible. The first, that the Jews from Palestine who came to India in about 35 a.d. should have met the very people who had known Issa when he was a student at Benares; the second, that this Sutra of Issa, composed in the first century of our era, should not have found a place either in the Kandjur or in the Tandjur.

It might, of course, be said, Why should the Buddhist monks of Himis have indulged in this mystification?—-but we know as a fact that Pandits in India, when hard pressed, have allowed themselves the same liberty with such men as Wilford and Jacolliot; why should not the Buddhist monks of Himis have done the same for M. Notovitch, who was determined to find a Life of Jesus Christ in Tibet? If this explanation, the only one I can think of, be rejected, nothing would remain but to accuse M. Notovitch, not simply of a mauvaise plaisanterie, but of a disgraceful fraud; and that seems a strong measure to adopt towards a gentleman who represents himself as on friendly terms with Cardinal Rotelli, M. Jules Simon, and E. Renan.

And here I must say that if there is anything that might cause misgivings in our mind as to M. Notovitch’s trustworthiness, it is the way in which he speaks of his friends. When a Cardinal at Rome dissuades him from publishing his book, and also kindly offers to assist him, he hints that this was simply a bribe, and that the Cardinal wished to suppress the book. Why should he? If the story of Issa were historically true, it would remove many difficulties. It would show once for all that Jesus was a real and historical character. The teaching ascribed to him in Tibet is much the same as what is found in the Gospels, and if there are some differences, if more particularly the miraculous element is almost entirely absent, a Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church would always have the tradition of the Church to rest on, and would probably have been most grateful for the solid historical framework supplied by the Tibetan Life.

M. Notovitch is equally uncharitable in imputing motives to the late M. Renan, who seems to have received him most kindly and to have offered to submit his discovery to the Academy. M. Notovitch |520 says that he never called on Renan again, but actually waited for his death, because he was sure that M. Renan would have secured the best part of the credit for himself, leaving to M. Notovitch nothing but the good luck of having discovered the Tibetan manuscript at Himis. Whatever else Renan was, he certainly was far from jealous, and he would have acted towards M. Notovitch in the same spirit with which he welcomed the discoveries which Hamdy Bey lately made in Syria on the very ground which had been explored before by Renan himself. Many travellers who discover manuscripts, or inscriptions, or antiquities, are too apt to forget how much they owe to good luck and to the spades of their labourers, and that, though a man who disinters a buried city may be congratulated on his devotion and courage and perseverance, he does not thereby become a scholar or antiquary. The name of the discoverer of the Rosetta stone is almost forgotten, the name of the decipherer will be remembered for ever.

The worst treatment, however, is meted out to the missionaries in Tibet. It seems that they have written to say that M. Notovitch had never broken his leg or been nursed in the monastery of Himis. This is a point that can easily be cleared up, for there are at the present moment a number of English officers at Leh, and there is the doctor who either did or did not set the traveller’s leg. M. Notovitch hints that the Moravian missionaries at Leh are distrusted by the people, and that the monks would never have shown them the manuscript containing the Life of Issa. Again I say, why not? If Issa was Jesus Christ, either the Buddhist monks and the Moravian missionaries would have seen that they both believed in the same teacher, or they might have thought that this new Life of Issa was even less exposed to objections than the Gospel story. But the worst comes at the end. ‚How can I tell,’ he writes, ‚that these missionaries have not themselves taken away the documents of which I saw the copies at the Himis monastery?’ But how could they, if the monks never showed them these manuscripts? M. Notovitch goes even further. ‚This is simply a supposition of my own,’ he writes, ‚but, if it is true, only the copies have been made to disappear, and the originals have remained at Lassa. … I propose to start at the end of the present year for Tibet, in order to find the original documents having reference to the life of Jesus Christ. I hope to succeed in this undertaking in spite of the wishes of the missionaries, for whom, however, I have never ceased to profess the profoundest respect.’ Any one who can hint that these missionaries may have stolen and suppressed the only historical Life of Christ which is known to exist, and nevertheless express the profoundest respect for them, must not be surprised if the missionaries and their friends retaliate in the same spirit. We still prefer to suppose that M. Notovitch, like Lieutenant Wilford, like M. Jacolliot, like Madame Blavatsky and Mr. Sinnet, was duped. |521 It is pleasanter to believe that Buddhist monks can at times be wags, than that M. Notovitch is a rogue.

All this, no doubt, is very sad. How long have we wished for a real historical life of Christ without the legendary halo, written, not by one of his disciples, but by an independent eye-witness who had seen and heard Christ during the three years of his active life, and who had witnessed the Crucifixion and whatever happened afterwards? And now, when we seemed to have found such a Life, written by an eye-witness of his death, and free as yet from any miraculous accretions, it turns out to be an invention of a Buddhist monk at Himis, or, as others would have it, a fraud committed by an enterprising traveller and a bold French publisher. We must not lose patience. In these days of unexpected discoveries in Egypt and elsewhere, everything is possible. There is now at Vienna a fragment of the Gospel-story more ancient than the text of St. Mark. Other things may follow. Only let us hope that if such a Life were ever to be discovered, the attitude of Christian theologians would not be like that which M. Notovitch suspects on the part of an Italian Cardinal or of the Moravian missionaries at Himis, but that the historical Christ, though different from the Christ of the Gospels, would be welcomed by all who can believe in his teaching, even without the help of miracles.

F. Max Müller.

P.S.—-It is curious that at the very time I was writing this paper I received a letter from an English lady dated Leh, Ladakh, June 29. She writes:

We left Leh two days ago, having enjoyed our stay there so much! There had been only one English lady here for over three years. Two German ladies live there, missionaries, a Mr. and Mrs. Weber—-a girl, and another English missionary. They have only twenty Christians, though it has been a mission-station for seven years. We saw a polo match which was played down the principal street. Yesterday we were at the great Himis monastery, the largest Buddhist monastery up here—-800 Lamas. Did you hear of a Russian who could not gain admittance to the monastery in any way, but at last broke his leg outside, and was taken in? His object was to copy a Buddhist Life of Christ which is there. He says he got it, and has published it since in French. There is not a single word of truth in the whole story! There has been no Russian there. No one has been taken into the Seminary for the past fifty years with a broken leg! There is no Life of Christ there at all! It is dawning on me that people who in England profess to have been living in Buddhist monasteries in Tibet and to have learnt there the mysteries of Esoteric Buddhism are frauds. The monasteries one and all are the most filthy places. The Lamas are the dirtiest of a very dirty race. They are fearfully ignorant, and idolaters pur et simple; no—-neither pure nor simple. I have asked many travellers whom I have met, and they all tell the same story. They acknowledge that perhaps at the Lama University at Lassa it may be better, but no Englishman is allowed there. Captain Bower (the discoverer of the famous Bower MS.) did his very best to get there, but failed. . . . We are roughing it |522 now very much. I have not tasted bread for five weeks, and shall not for two months more. We have ‚chappaties’ instead. We rarely get any butter. We carry a little tinned butter, but it is too precious to eat much of. It was a great luxury to get some linen washed in Leh, though they did starch the sheets. „We are just starting on our 500 miles march to Simla. We hear that one pass is not open yet, about which we are very anxious. We have one pass of 18,000 feet to cross, and we shall be 13,000 feet high for over a fortnight; but I hope that by the time you get this we shall be down in beautiful Kulu, only one month from Simla!

The Nineteenth Century, 39 (January-June 1896) pp. 667-677

THE CHIEF LAMA OF HIMIS ON THE ALLEGED ‚UNKNOWN LIFE OF CHRIST’

It is difficult for any one resident in India to estimate accurately the importance of new departures in European literature, and to gauge the degree of acceptance accorded to a fresh literary discovery such as that which M. Notovitch claims to have made. A revelation of so surprising a nature could not, however, have failed to excite keen interest, not only among theologians and the religious public generally, but also among all who wish to acquire additional information respecting ancient religious systems and civilisations.

Under these circumstances it was not surprising to find in the October (1894) number of this Review an article from the able pen of Professor Max Müller dealing with the Russian traveller’s marvellous ‚find.’

I confess that, not having at the time had the pleasure of reading the book which forms the subject of this article, it seemed to me that the learned Oxford Professor was disposed to treat the discoverer somewhat harshly, in holding up the Unknown Life of Christ as a literary forgery, on evidence which did not then appear conclusive.

A careful perusal of the book made a less favourable impression of the genuineness of the discovery therein described; but my faith in M. Notovitch was somewhat revived by the bold reply which that gentleman made to his critics, to the effect that he is ‚neither a „hoaxer” nor a „forger,” ‚ and that he is about to undertake a fresh journey to Tibet to prove the truth of his story.

In the light of subsequent investigations, I am bound to say that the chief interest which attaches, in my mind, to M. Notovitch’s daring defence of his book is the fact that that defence appeared immediately before the publication of an English translation of his work.

I was resident in Madras during the whole of last year, and did not expect to have an opportunity of investigating the facts respecting the Unknown Life of Christ at so early a date. Removing to the North-West Provinces in the early part of the present year, I |668 found that it would be practicable during the three months of the University vacation to travel through Kashmir to Ladakh, following the route taken by M. Notovitch, and to spend sufficient time at the monastery at Himis to learn the truth on this important question. I may here mention, en passant, that I did not find it necessary to break even a little finger, much less a leg, in order to gain admittance to Himis Monastery, where I am now staying for a few days, enjoying the kind hospitality of the Chief Lama (or Abbot), the same gentleman who, according to M. Notovitch, nursed him so kindly under the painful circumstances connected with his memorable visit.

Coming to Himis with an entirely open mind on the question, and in no way biassed by the formation of a previous judgment, I was fully prepared to find that M. Notovitch’s narrative was correct, and to congratulate him on his marvellous discovery. One matter of detail, entirely unconnected with the genuineness of the Russian traveller’s literary discovery, shook my faith slightly in the general veracity of the discoverer.

Daring his journey up the Sind Valley M. Notovitch was beset on all sides by ‚panthers, tigers, leopards, black bears, wolves, and jackals.’ A panther ate one of his coolies near the village of Haďena before his very eyes, and black bears blocked his path in an aggressive manner. Some of the old inhabitants of Haďena told me that they had never seen or heard of a panther or tiger in the neighbourhood, and they had never heard of any coolie, travelling with a European sahib, who had lost his life in the way described. They were sure that such an event had not happened within the last ten years. I was informed by a gentleman of large experience in big-game shooting in Kashmir that such an experience as that of M. Notovitch was quite unprecedented, even in 1887, within thirty miles of the capital of Kashmir.

During my journey up the Sind Valley the only wild animal I saw was a red bear of such retiring disposition that I could not get near enough for a shot.

In Ladakh I was so fortunate as to bag an ibex with thirty-eight-inch horns, called somewhat contemptuously by the Russian author ‚wild goats;’ but it is not fair to the Ladakhis to assert, as M. Notovitch does, that the pursuit of this animal is the principal occupation of the men of the country. Ibex are now so scarce near the Leh-Srinagar road that it is fortunate that this is not the case. M. Notovitch pursued his path undeterred by trifling discouragements, ‚prepared,’ as he tells us, ‚ for the discovery of a Life of Christ among the Buddhists.’

In justice to the imaginative author I feel bound to say that I have no evidence that M. Notovitch has not visited Himis Monastery. On the contrary, the Chief Lama, or Chagzot, of Himis |669 does distinctly remember that several European gentlemen visited the monastery in the years 1887 and 1888.

I do not attach much importance to the venerable Lama’s declaration, before the Commissioner of Ladakh, to the effect that no Russian gentleman visited the monastery in the years named, because I have reason to believe that the Lama was not aware at the time of the appearance of a person of Russian nationality, and on being shown the photograph of M. Notovitch confesses that he might have mistaken him for an ‚English sahib.’ It appears certain that this venerable Abbot could not distinguish at a glance between a Russian and other European or American traveller.

The declaration of the ‚English lady at Leh,’ and of the British officers, mentioned by Professor Max Millier, was probably founded on the fact that no such name as Notovitch occurs in the list of European travellers kept at the dâk bungalow in Leh, where M. Notovitch says that he resided during his stay in that place. Careful inquiries have elicited the fact that a Russian gentleman named Notovitch was treated by the medical officer of Leh Hospital, Dr. Karl Marks, when suffering not from a broken leg, but from the less romantic but hardly less painful complaint—-toothache.

I will now call attention to several leading statements in M. Notovitch’s book, all of which will be found to be definitely contradicted in the document signed by the Chief Superior of Himis Monastery, and sealed with his official seal. This statement I have sent to Professor Max Müller for inspection, together with the subjoined declaration of Mr. Joldan, an educated Tibetan gentleman, to whose able assistance I am deeply indebted.

A more patient and painstaking interpreter could not be found, nor one better fitted for the task.

The extracts from M. Notovitch’s book were slowly translated to the Lama, and were thoroughly understood by him. The questions and answers were fully discussed at two lengthy interviews before being prepared as a document for signature, and when so prepared were carefully translated again to the Lama by Mr. Joldan, and discussed by him with that gentleman, and with a venerable monk who appeared to act as the Lama’s private secretary.

I may here say that I have the fullest confidence in the veracity and honesty of this old and respected Chief Lama, who appears to be held in the highest esteem, not only among Buddhists, but by all Europeans who have made his acquaintance. As he says, he has nothing whatever to gain by the concealment of facts, or by any departure from the truth.

His indignation at the manner in which he has been travestied by the ingenious author was of far too genuine a character to be feigned, and I was much interested when, in our final interview, he asked me if in Europe there existed no means of punishing a person |670 who told such untruths. I could only reply that literary honesty is taken for granted to such an extent in Europe, that literary forgery of the nature committed by M. Notovitch could not, I believed, be punished by our criminal law.

With reference to M. Notovitch’s declaration that he is going to Himis to verify the statements made in his book, I would take the liberty of earnestly advising him, if he does so, to disguise himself at least as effectually as on the occasion of his former visit. M. Notovitch will not find himself popular at Himis, and might not gain admittance, even on the pretext of having another broken leg.

The following extracts have been carefully selected from the Unknown Life of Christ, and are such that on their truth or falsehood may be said to depend the value of M. Notovitch’s story.

After describing at length the details of a dramatic performance, said to have been witnessed in the courtyard of Himis Monastery, M. Notovitch writes:

A fter having crossed the courtyard and ascended a staircase lined with prayer-wheels, we passed through two rooms encumbered with idols, and came out upon the terrace, where I seated myself on a bench opposite the venerable Lama, whose eyes flashed with intelligence (p. 110).

(This extract is important as bearing on the question of identification; see Answers 1 and 2 of the Lama’s statement: and it may here be remarked that the author’s account of the approach to the Chief Lama’s reception room and balcony is accurate.) Then follows a long résumé of a conversation on religious matters, in the course of which the Abbot is said to have made the following observations amongst others:

We have a striking example of this (Nature-worship) in the ancient Egyptians, who worshipped animals, trees, and stones, the winds and the rain (p. 114).

The Assyrians, in seeking the way which should lead them to the feet of the Creator, turned their eyes to the stars (p. 115).

Perhaps the people of Israel have demonstrated in a more flagrant manner than any other, man’s love for the concrete (p. 115).

The name of Issa is held in great respect by the Buddhists, but little is known about him save by the Chief Lamas who have read the scrolls relating to his life (p. 120).

The documents brought from India to Nepal, and from Nepal to Tibet, concerning Issa’s existence, are written in the Pâli language, and are now in Lassa; but a copy in our language—-that is, the Tibetan—-exists in this convent (p. 123).

Two days later I sent by a messenger to the Chief Lama a present comprising an alarum, a watch, and a thermometer (p. 125).

We will now pass on to the description given by the author of his re-entry into the monastery with a broken leg:

I was carried with great care to the best of their chambers, and placed on a bed of soft materials, near to which stood a prayer-wheel. All this took place under the immediate surveillance of the Superior, who affectionately pressed the hand I offered him in gratitude for his kindness (p. 127).

While a youth of the convent kept in motion the prayer-wheel near my bed, |671 the venerable Superior entertained me with endless stories, constantly taking my alarum and watch from their cases, and putting me questions as to their uses, and the way they should be worked. At last, acceding to my earnest entreaties, he ended by bringing me two large bound volumes, with leaves yellowed by time, and from them he read to me, in the Tibetan language, the biography of Issa, which I carefully noted in my carnet de voyage, as my interpreter translated what he said (p. 128).

This last extract is in a sense the most important of all, as will be seen when it is compared with Answers 3, 4, and 5 in the statement of the Chief Superior of Himis Monastery. That statement I now append. The original is in the hands of Professor Max Müller, as I have said, as also is the appended declaration of Mr. Joldan, of Leh.

The statement of the Lama, if true—-and there is every reason to believe it to be so—-disposes once and for ever of M. Notovitch’s claim to have discovered a Life of Issa among the Buddhists of Ladakh. My questions to the Lama were framed briefly, and with as much simplicity as possible, so that there might be no room for any mistake or doubt respecting the meaning of these questions.

My interpreter. Mr. Joldan, tells me that he was most careful to translate the Lama’s answers verbally and literally, to avoid all possible misapprehension. The statement is as follows:

Question 1. You are the Chief Lama (or Abbot) of Himis Monastery?

Answer 1. Yes.

Question 2. For how long have you acted continuously in that capacity?

Answer 2. For fifteen years.

Question 3. Have you or any of the Buddhist monks in this monastery ever seen here a European with an injured leg?

Answer 3. No, not during the last fifteen years. If any sahib suffering from serious injury had stayed in this monastery it would have been my duty to report the matter to the Wazir of Leh. I have never had occasion to do so.

Question 4. Have you or any of your monks ever shown any Life of Issa to any sahib, and allowed him to copy and translate the same?

Answer 4. There is no such book in the monastery, and during my term of office no sahib has been allowed to copy or translate any of the manuscripts in the monastery.

Question 5. Are you aware of the existence of any book in any of the Buddhist monasteries of Tibet bearing on the life of Issa?

Answer 5. I have been for forty-two years a Lama, and am well acquainted with all the well-known Buddhist books and manuscripts, and I have never heard of one which mentions the name of Issa, and it is my firm and honest belief that none such exists. I have inquired of our principal Lamas in other monasteries of Tibet, and they are not acquainted with any books or manuscripts which mention the name of Issa.

Question 6. M. Nicolas Notovitch, a Russian gentleman who visited |672 your monastery between seven and eight years ago, states that you discussed with him the religions of the ancient Egyptians, Assyrians, and the people of Israel.

Answer 6. I know nothing whatever about the Egyptians, Assyrians, and the people of Israel, and do not know anything of their religions whatsoever. I have never mentioned these peoples to any sahib.