W Anuradhapurze znajduje się wyjątkowe miejsce – zbudowana wśród skalnych występów buddyjska świątynia Isurumuniya. Zbudowana za króla Dewanampii Tissy, pochodzi z III wieku p.n.e. Została wzniesiona dla około 500 dzieci z najwyższej kasty, które zostały wyświęcone na mnichów i tam właśnie zamieszkiwały. Ta świątynia była pierwszym sanktuarium na Cejlonie , w którym przechowywano najświętszą relikwię lankijskiego Buddyzmu „Ząb Buddy”.Wchodzi się do niej po schodach przez ganek, a w środku wędruje się po kamiennych ścieżkach i stopniach.

W Anuradhapurze znajduje się wyjątkowe miejsce – zbudowana wśród skalnych występów buddyjska świątynia Isurumuniya. Zbudowana za króla Dewanampii Tissy, pochodzi z III wieku p.n.e. Została wzniesiona dla około 500 dzieci z najwyższej kasty, które zostały wyświęcone na mnichów i tam właśnie zamieszkiwały. Ta świątynia była pierwszym sanktuarium na Cejlonie , w którym przechowywano najświętszą relikwię lankijskiego Buddyzmu „Ząb Buddy”.Wchodzi się do niej po schodach przez ganek, a w środku wędruje się po kamiennych ścieżkach i stopniach.

Zacznijmy od tego że warto wiedzieć iż Budda był Indoeuropejczykiem. My nazywamy go Bydtą, Bytą (Bądtą) – Będącym, Będącym Bytem, czyli Świadomym Istoty Bytu, Bycia – Istoty Świata i Istoty Samego Siebie. Być to istnieć Tu i Teraz, co jest istotą buddyjskiej medytacji i istotą oświecenia, istotą stanu „bez myślenia”. Po prostu istniejesz i tylko w tym stanie umysłu możesz zostać oświecony.

Czy polskie być zawiera istotę pojęcia Budda? A może w stosunku do sanskrytu i innych języków południowej Azji (w tym pali) pogłębia i rozszerza ono znaczenie i zakres pojęcia, nadając mu jeszcze bardziej transcendentalny wymiar?

Czy w ogóle wolno dokonać takiego tłumaczenia imienia Buddy – wprost, bez słownika? A jeśli tak, to czy nie zyskujemy dzięki takiemu zabiegowi całej gamy rozszerzających owo pojęcie sanskryckie sensów i skojarzeń. Czy pojęcie Awesta rzeczywiście odpowiada znaczeniem słowu Obwiesta? Przeczytajcie arcyciekawy artykuł o języku pali i polskim. Zwracam uwagę, że podobieństwa te muszą pochodzić najpóźniej z III wieku p.n.e., kiedy powstała Theravada. [C.B.]

♦

Z Wikipedii

Pāli (język pālijski; z sanskrytu pāli (पाऴि) = ‚szereg, wiersz, kanon’) – wymarły język średnioindyjski z grupy indoaryjskiej języków indoeuropejskich, wykazujący duże podobieństwo do języka wedyjskiego i sanskrytu klasycznego.

W języku tym powstało wiele tekstów literackich i religijnych w okresie od III w. p.n.e. Na szczególną uwagę zasługuje tzw. kanon palijski – Tipiṭaka, zbiór ksiąg kanonicznych wczesnych szkół buddyjskich.

Język pāli jest nadal używany jako język liturgiczny przez buddystów na Cejlonie i w Azji Południowo-Wschodniej – wyznających tradycję theravāda.

Zacznijmy od tego że warto wiedzieć iż Budda był Indoeuropejczykiem. My nazywamy go Bydtą, Bytą (Bądtą) – Będącym, Będącym Bytem, czyli Świadomym Istoty Bytu, Bycia – Istoty Świata i Istoty Samego Siebie. Być to istnieć Tu i Teraz, co jest istotą buddyjskiej medytacji i istotą oświecenia, istotą stanu „bez myślenia”. Po prostu istniejesz i tylko w tym stanie umysłu możesz zostać oświecony.

Czy polskie być zawiera istotę pojęcia Budda? A może w stosunku do sanskrytu i innych języków południowej Azji (w tym pali) pogłębia i rozszerza ono znaczenie i zakres pojęcia, nadając mu jeszcze bardziej transcendentalny wymiar?

Czy w ogóle wolno dokonać takiego tłumaczenia imienia Buddy – wprost, bez słownika? A jeśli tak, to czy nie zyskujemy dzięki takiemu zabiegowi całej gamy rozszerzających owo pojęcie sanskryckie sensów i skojarzeń. Czy pojęcie Awesta rzeczywiście odpowiada znaczeniem słowu Obwiesta? Przeczytajcie arcyciekawy artykuł o języku pali i polskim. Zwracam uwagę, że podobieństwa te muszą pochodzić najpóźniej z III wieku p.n.e., kiedy powstała Theravada.

♦

Z Wikipedii

Pāli (język pālijski; z sanskrytu pāli (पाऴि) = ‘szereg, wiersz, kanon’) – wymarły język średnioindyjski z grupy indoaryjskiej języków indoeuropejskich, wykazujący duże podobieństwo do języka wedyjskiego i sanskrytu klasycznego.

W języku tym powstało wiele tekstów literackich i religijnych w okresie od III w. p.n.e. Na szczególną uwagę zasługuje tzw. kanon palijski – Tipiṭaka, zbiór ksiąg kanonicznych wczesnych szkół buddyjskich.

Język pāli jest nadal używany jako język liturgiczny przez buddystów na Cejlonie i w Azji Południowo-Wschodniej – wyznających tradycję theravāda.

[Od razu pozwolę sobie zauważyć dwie rzeczy: palijski – po polsku znaczy palikowy, palowy, szeregowy, liniowy – jak w palisada – szereg pali ułożonych w linii. A więc w czasach gdy mógł być współużytkowany i język i zapis jako wspólny przez Słowian i Indo-Irańczyków – w tym mieszkających dziś na Sri Lance ludzi pochodzących od linii DNA R1a1a, być może określali oni ten rodzaj zapisu wspólnie jako palikowy, palowy, co było nazwą wspólną i pozostaje wciąż w języku polskim na określenie – zaostrzonego słupa – pala, palika, i szeregu słupów – palisada, a przetrwało na Sri Lance i Indiach, jako określenie szeregowego zapisu. To jedna uwaga – a druga? Spójrzmy jak wygląda ten zapis – Czy nie przypomina on węzełkowego pisma o którym wciąż się tyle spekuluje jako zapisie wici i kob Słowian? Ja widzę uderzające podobieństwo – także do zapisu Księgi Welesowej, który jest jakby podwieszonym pod linią ciągiem różnych „palików” – i tutaj widać jakby tę samą ciągłą linię u góry z której zwisają litery – „paliki” pionowe. Czyżby jednak obydwa te pisma i głagolica wywodziły się z zapisu sznurowego, a to szło także od zdobień sznurowych na ceramice? C. B.]

Na skałach znajdują się wspaniałe rzeźby miedzy innymi siedzący w królewskiej pozie mężczyzna z zamyśloną miną.

Theravada

Therawada (pāli: थेरवाद theravāda; sanskr. स्थविरवाद sthaviravāda; dosł. „nauka starszych”) – jest najdłużej istniejącą szkołą buddyjską spośród wczesnych szkół buddyjskich. Jej zwolenników zwiemy theravādinami, dosł. „głoszącymi (-vādin) [to, co nauczają] starsi” (thera), czyli mistrzowie, nauczyciele wywodzący swą naukę bezpośrednio od Buddy.

Przez kilka wieków była religią dominującą na Sri Lance (78% [1]) i w kontynentalnej, Południowo-Wschodniej Azji (południowo-wschodnia część Chin, Kambodża, Laos, Birma i Tajlandia). Zyskuje sobie także popularność w Singapurze i Australii. Wyodrębniona poprzez schizmę, która miała miejsce na III soborze buddyjskim (Pāṭaliputra, 250 p.n.e.), która miała odłączyć się od „nauki starszych” (kierujących zakonem (sanghą). Termin „theravāda” po raz pierwszy pojawia się w VII w. w manuskryptach należących do nich samych. Owe manuskrypty mówią, iż szkoła pragnie zachować autentyczne nauki Buddy Śākyamuniego. Wyznawcy tej tradycji wywodzą swą linię od sthaviravādinów (pālijskie: thera = sanskryckie: sthavira) od których oddzielili się mahāsaṃghikowie na II soborze buddyjskim (Vesali, 383 p.n.e.) kiedy to mnisi pod przewodnictwem Mahākassapy Thery zajęli ortodoksyjną pozycję przestrzegania wszystkich „pomniejszych i pośrednich” przykazań ustanowionych przez Buddę Gotamę. Do dzisiaj tę tradycję uważa się za radykalną, konserwatywną i ortodoksyjną.

Najbardziej znanymi, zachowanymi w świątyni są posągi Buddy medytującego oraz Buddy leżącego, wchodzącego w nirwanę, o długości 17 metrów.

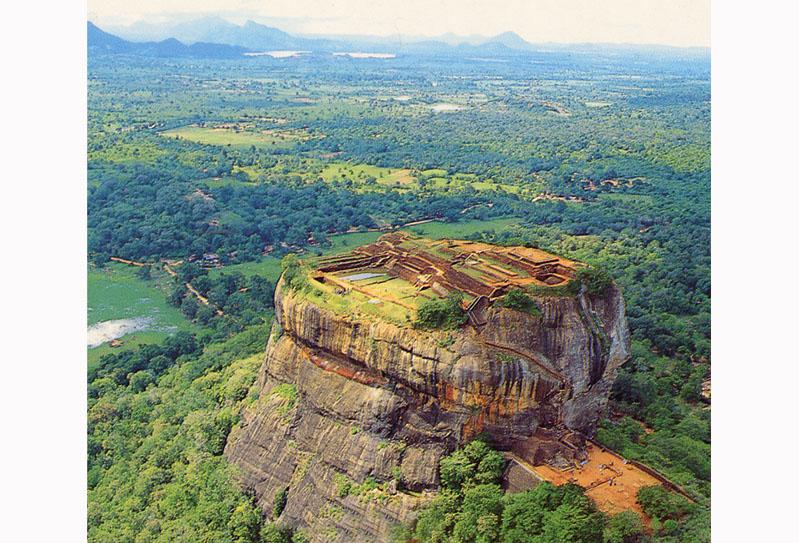

Mała, biała dogoba powyżej urwiska jest jakby przyrośnięta do skał. Zespół świątynny jest idealnie wpisany w skalne otoczenie i pod tym względem nie ustępuje innym sakralnym budowlom na Sri Lance, jak choćby Lwiej Skale w Sigiriyi. Po obu stronach szczeliny skalnej nad którą wznosi się świątynia, znajdują się baseny służące kiedyś do rytualnych obmyć mnichów buddyjskich.

Theravada- Stara wiedza, wodzący i wiedzący czyli nauczyciele, ale także znawcy, posiadający wiedzę i widzący lepiej i głębiej, – a więc mistrzowie, wiedunowie, wieszczowie – górytowie, górowie (guru). Jeszcze większą wierność przekładu i podobieństwo do polskiego stary, starej wiary (chociaż rosyjskie przecież prawie się nie różni staryj, starik, staroj wiery) – wykazuje sanskryckie – sthavira [stha(ra)vira]

♦

Szerokie badania podobieństw językowych między językami słowiańskimi i indo-irańskimi toczą się nie od dzisiaj i wynikają często z działania innych naszych braci w Wierze Przyrodzonej, którzy na przykład tłumaczą na polski teksty Wed czy inne święte teksty hinduistyczne, buddyjskie, zenistyczne, awestyjskie, manichejskie. Te podobieństwa są zauważane od dawna i są z nich wyciągane wnioski.

Jeszcze w latach 80-tych (1989) spotkałem bardzo ciekawego człowieka, Polaka, Adama Wojtanka (późniejszego założyciela Grupy Wyznaniowej „Shri Vidya”, który już wtedy napisał duże opracowanie na temat tych podobieństw, ale oczywiście jako iż nie był językoznawcą, ani nie był członkiem PZPR, któż by się wtedy w Polsce tą jego pracą zainteresował. Jemu – jak każdemu odkrywcy – zależało bardzo nie tyle na tym żeby się stać sławnym, co na tym żeby ludzie się nad tym zastanowili, a fachowcy wzięli tę sprawę w swoje ręce. Ponieważ nikogo to nie obeszło i schodził Kraków, Warszawę i Wrocław na darmo, a w gruncie rzeczy chciał się zajmować zupełnie czym innym, w końcu przestał wydeptywać szlaki, zostawił papiery w Zielonych Brygadach, zostawił odbitkę ksero u mnie i wyjechał robić to co całe życie robić zamierzał – oddać się praktyce buddyjskiej w Nepalu, Indiach i na Sri Lance, tworzyć muzykę w USA.

Potem w latach dziewięćdziesiątych gościłem z Ewą Ryn pewnego profesora z Bostonu, który był z pochodzenia Cejlończykiem, ale żył w Bostonie i miał za przyjaciela innego profesora z Bostonu – Żyda polskiego pochodzenia, którego też dwukrotnie gościliśmy. Łączyło ich to że razem pracowali na wydziale slawistycznym owego bostońskiego Uniwersytetu i tam wykładali. Obaj oni, już 30 lat temu, doszli do tych samych wniosków na temat podobieństw językowych indo-irańskich i słowiańskich – Te języki stanowiły kiedyś wspólną grupę i jest to wspólnota prastara!!! – stwierdzili.

No ale przecież według prześwietnych polskich naukowców lat 70-tych, 80-tych, 90-tych XX wieku, lat 00-zerowych a teraz i lat 10-tych XXI wieku – języki Słowian wykształciły się gdzieś w III- V wieku n.e – no i nie zróżnicowały się za bardzo, jakby był jeden język z gwarami jakimiś (dziwactwo, patrzcie ludzie!) więc muszą być „młodziutkie” jak pierwszy wiosenny szczypiorek. Jakim cudem słownictwo Wed czy Awesty może być wspólne dla Słowian, Hindusów i Irańczyków??? – powiadali – Tamto to starożytność a Słowianie wykluli się jako ostatnie brzydkie kaczątko we wszechświecie koło X wieku kiedy ich chrześcijańscy księża nauczyli „pisati „i „czitati” bukwy (bukwy – to oczywiście germańska pożyczka, jak i księga i ksiądz i książę – bo buk – to jest niemiecka nazwa drzewa nieznanego Słowianom, a książka to jest coś co się tym oraczom i niewolnikom w ogóle nie śniło). Może w XV wieku ktoś coś stamtąd przywlókł do „ciemnej” Polski, z tego wszetecznego zoroastryjskiego Iranu i z tej wszetecznej kamasutryjskiej Indii???

I mimo że minęło tyle lat, i tyle się w świecie – także nauki – zmieniło, powiadają dalej to samo.

Ponieważ jednak na pewno nie przypadkiem – a boskim zrządzeniem – otrzymałem po raz trzeci w życiu szansę i przysłano mi po przeczytaniu mojego blogu wspaniały artykuł na ten sam temat po raz kolejny ze Sri Lanki, i zrobił to polski mnich buddyjski, który tam praktykuje i na co dzień tłumaczy teksty święte w różne strony – na polski, na pali, na angielski – publikujemy ten materiał. Jest to zupełnie inna osoba – nie mająca nic wspólnego z moim pierwszym znajomym z lat siedemdziesiątych, ani ze znajomymi językoznawcami z Bostonu.

Mam świadomość, że nie każdy statystyczny Polak, a nawet człowiek na Ziemi, ma prawdopodobną statystycznie szansę trzykrotnie, z trzech różnych niezależnych źródeł otrzymać trzy razy tekst na ten sam temat. Sadzę że otrzymałem go bo już najwyższy czas, go opublikować w Polsce.

Buddyzm i Zen to wysublimowane kontynuacje tej samej Prastarej Wiary Przyrody, która wydała Wedy i naszą słowiańską Baję. W świetle dowodów genetycznych wspólnota językowa zwana praindoeuropejską, która w istocie prawidłowo powinna być zwana – wspólnotą Słowiano-Indo-Irańską, nie powinna dzisiaj nikogo dziwić.

Serdeczne pozdrowienia dla tych wszystkich niedowiarków, którzy stojąc dzisiaj na głowie i trzymając się prawą ręką za lewe ucho nadal usiłują niczego nowego nie widzieć i wytrwale dowodzą wyższości niemieckiej rasy używając dzisiaj Celtów jako „zastępczych” Germanów (tylko że Celtowie to też grupa kentum – wtórna do Słowian, Irańczyków i Hindusów Aryjskich).

C. B.

Oto więc zapowiedziany artykuł – niestety w języku angielskim, bo to język międzynarodowy i język naukowego dyskursu:

Vilāsa Bhikkhu

WWW.Sasana.pl

COMMON FEATURES BETWEEN PĀḶI AND POLISH

Introduction

Identification with a certain system of belief is one of the most important conditions for devotees to participate in a religious movement. That is why sacred sets of values are sometimes called “religious traditions”. The word “tradition” in today’s modernized world might be despised and looked down upon. Some might say that “…beliefs and traditions handed down in a society tend to become crystallized into dead forms which suppress individual vitality”. Such a statement on the one hand is perfectly true – if a tradition is stagnant and not applicable to the reality and actuality, surely it does more harm to people who believe in it.

On the other hand we need to emphasize that Buddhism does not fall so easily into this dreadful pattern. One reason would be that it has its tremendous power of staying relevant and practical even in the XXI century. To test it lets answer these questions:

“Does a given individual’s religion serve to break his will, keep him at an infantile level of development, and enable him to avoid the anxiety of freedom and personal responsibility? Or does it serve him as a basis of meaning which affirms his dignity and worth, which gives him a basis for courageous acceptance of his limitations and normal anxiety, but which aids him to develop his powers, his responsibility and his capacity to love his fellow men? “

Answering briefly to these issues is going to be important in the progress of this thesis, so let us focus on these inquiries for a moment.

Buddhism is actually all about freedom! Not only that Buddha pointed out the way to final liberation – Nibbāna, but he also said: “(…) just as the ocean has a single taste — that of salt — in the same way, this Doctrine and Discipline has a single taste: that of release…” [Ud 5.5 – Uposatha Sutta – trans. by Thanissaro Bhikkhu = T.B.] Of course the most famous sutta answering all these questions is the Kālāma Sutta which states:

“So in this case, Kālāmas, don’t go by reports, by legends, by traditions, by scripture, by logical conjecture, by inference, by analogies, by agreement through pondering views, by probability, or by the thought, ‚This contemplative is our teacher.’ When you know for yourselves that, ‚These qualities are unskillful; these qualities are blameworthy; these qualities are criticized by the wise; these qualities, when adopted and carried out, lead to harm and to suffering’ — then you should abandon them.” [AN 3.65 – Kālāma Sutta – trans. T.B.]

The second reason might be that Buddhism does not subordinate easily under the term “religion”. The word comes from re- + ligre, to bind; [see leig- in Indo-European Roots.] If we interpret this as a binding with God or some supernatural force – then definitely Buddha Dhamma is something completely opposite. As it was proved by quotation above – the main purpose of a Buddhist follower is to break free, not to bind himself to something or someone. Yet if we want to interpret this as a bond between the people in general who worship a certain ideal, like the Triple Gem, than it would be more understandable. Yet for that reason the word Saṃgha would be much more appropriate. It is possible that the root comes from O-grade form of *som-. It may refer to saṃhita, saṃsāra, sandhi, Saṅkhyā, sannyasi, Sanskrit, from Sanskrit saṁ, together [polish – ra-zem = together; also (polish –są-siad – OCS sǫ-sědъ “Neighbor”, compare O.Ind. saṁ-sád- “congregation, meeting”), where saṁ could also mean “well”, as in saṁskrta = “well arranged”].

The reason why I briefly pointed out these arguments is that in accordance with the introduction of Buddhism to Polish people, by translation of the Suttas from Pāḷi, one has to have in mind that this is not a case of establishing a new religious movement, nor is it a sort of “buddhisation” of Polish society. It is a spiritual relief during the crisis – just like after a natural disaster, other countries send some kind of help – in a similar way Buddhism should be viewed as an aid which might help those who are in bad shape (from the spiritual point of view) and who need some counseling. Buddhism might be seen as a sort of charity organization which tries to help those who are suffering.

As much as it is needed everywhere in the West, the issue of a grounded tradition arises. Western societies sometimes are flooded with oriental and exciting movements and quasi-religions which last for some time and diminish quickly as well. The reason is that there is no link which could – let’s say – “bind together” the neophytes with the “new faith”. That is why all the New Age movements, all the Hare-Krishnas and all others of these kinds are bound to fail after some time. If one wants Buddhism to last in a new country one has to find some sort of fundament, which is not only related to the new doctrine, but is already seeded in the receiving society. In other words there has to be a common ground so that it will be easily accessible for newcomers.

I believe that this link joining and making the necessary connection between Buddhism and Polish society might be the language – Pāḷi.

Scythians and kurgans

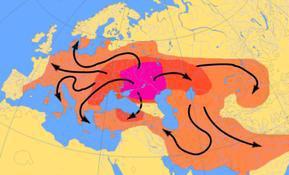

In ancient times, when the Indo-European tribes were once more or less unified group of people, living somewhere in today’s territory of Ukraine and southern Russia (according to Kurgan theory – see below), the religious practices, systems of belief, as well as culture and customs, were once the same for proto-Slavs who migrated west as well as for proto-Aryans who made the Indian peninsula their homeland. Most importantly though, the two ancient groups might have been connected by something, which can be traced through scientific research.

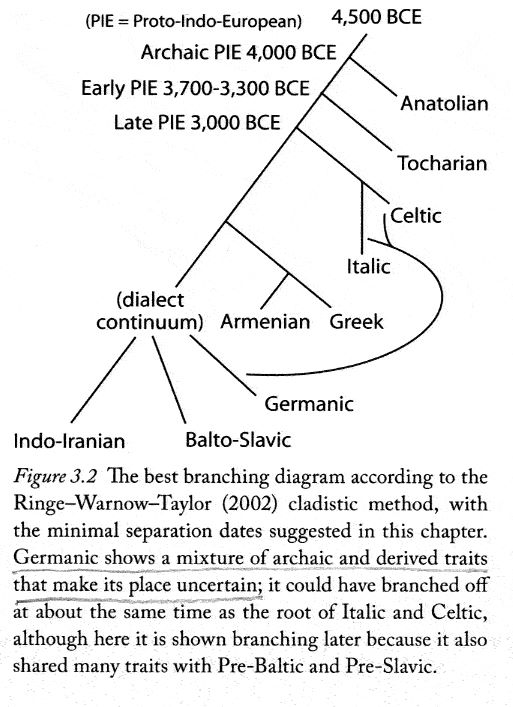

It is said that in ancient times all the Indo-European tribes were speaking the same language, the Proto-Indo-European.

Such a statement is claimed by the Kurgan hypothesis. The term is derived from kurgan (Polish: kurhan) meaning a burial mound or a castle. The Kurgan model is the most widely accepted scenario of Indo-European origins, although alternate theories such as the Anatolian “urheimat” also have some support. The Kurgan hypothesis was first formulated in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas. According to her, the ancient Indo-European people were nomadic tribes who in the early 3rd millennium BC expanded throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.

One may ask: what is so significant about links between Polish and Pāḷi? In other European languages we also might trace similarities, so what makes it different? To answer this question let’s define the parts of this puzzle first, in order to put them together later on. The first piece of the puzzle is mentioned above – the Kurgan model. Now let us focus on the divisions in the languages that evolved from the Indo-European family tree.

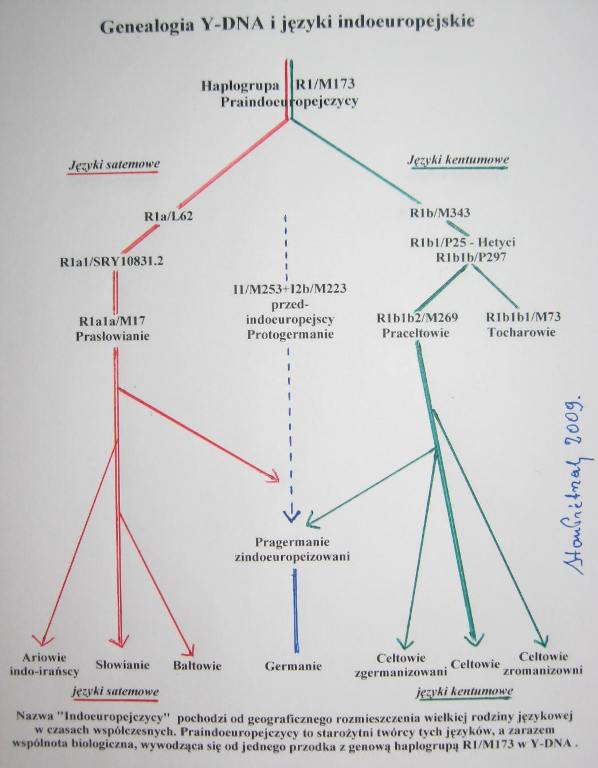

There are two major branches of Indo-European: satəm and kentum (centum). Languages belonging to the satəm family are: the Baltic languages (Lithuanian, Latvian, Old Prussian† – cross symbol means that the language is extinct). Worth mentioning is the fact that Baltic languages are most closely approximate to the Slavic languages. Some similarities, mainly phonetic, features of the Slavic languages, are also encountered in the following satəm languages: Albanian, Illyrian†, Thracian†, Armenian, Indo-Iranian (Indic: Sanskrit†, Hindi, Bengali, Nepali, Gipsy <Romany>; Dardic: Kashmiri; Kafir <Nuristani>; Iranian: Avestan†, Farsi <Persian>, Tadjik, Kurdish, Ossetic, Pashto <Afghan>). All these languages are termed satəm.

The other languages of the Indo-European family, termed kentum (centum), are: Anatolian† (Hittite†, Luwian†), Tocharian†, Hellenic (Greek), (Old) Macedonian†, Phrygian†, Messapic†, Germanic (English, German, Yiddish, Dutch, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Icelandic, Gothic†), Celtic (Welsh, Breton, Irish, Scots Gaelic), Italic (Latin†, Oscan†, maybe Venetic†) and Romance languages (Romanian, Italian, French, Provincial <Provençal, Occitan>, Catalan, Portuguese, Spanish).

Of course Slavic languages belong to the satəm group, sharing many common words and roots of words with the Indic family of languages. The Pāḷi language is also included in the same group – thus making the kentum (centum) group a bit more distant. This fact is also very important, as we shall find out later on.

What might be controversial and what many people might reject is a suggestion that these facts are connected with each other. Let us consider another part of the puzzle – the Scythians.

The Scythians are mostly defined as horse-riding nomads, who dominated the Pontic-Caspian steppe. Scholars include them in the Iranian family of Indo-Europeans. Many believe that the name „Scythian” has also been used to refer to various peoples seen as similar to the Scythians, or who lived anywhere in a vast area covering present-day Ukraine, Russia and Central Asia.

Worth mentioning is the fact that the ancient Persians called all the Scyths „Saca” (Herodotus .VII 64). Their principal tribe, the Royal Scyths, ruled the vast lands occupied by the nation as a whole (Herodotus .IV 20); and they called themselves Skolotoi. Oswald Szemerényi devotes a thorough discussion to the etymology of the word Scyth in his work „Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian – Saka”. The related words derive from *skuza, an ancient Indo-European word for archer (polish: strzelec=archer, shooter), hence Iranian Ishkuzi = archers. The Scythians first appeared in the historical record in the 8th century BC. If we look at the name of this tribe we might find a strange familiarity to the name of a Sakya tribe – Prince Siddhartha’ kin.

The Pāḷi word for archer is “issāsa” (pol: strzelec), for archery – “issattha” – than we could easily put one more name to Szemerényi’s line of names – Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian – Saka – Sakya – and all of them would refer to the same group of people who might have invaded the Indian peninsula and established some power over autochthon people there. Of course we need to define the timeline – that is when exactly the Scyths appeared, and were they truly the Buddha’s ancestors.

There is a certainty about the link between Scythians and kurgans – Scythian élites made kurgan tombs: high barrows heaped over chamber-tombs of larch-wood — a deciduous conifer that may have had special significance as a tree of life-renewal, for it stands bare in winter. These „Royal kurgans” contained the „Scythian triad” of weapons, horse-harness, and Scythian-style wild-animal art – for example in a later period Scythians were actually using a Buddhist triratana symbol – like the pictured silver coin of King Azes II (r.c. 35-12 BC). Archeologists have no doubt about the technological advancement of Scythian goldsmiths, especially for creating fine gold jewelry, etc. Because of their other achievements such as horseback-riding, the usage of the wheel (and the first war-chariots being used by them) they could easily subdue a conquered nation, imposing their own administrative system, language and religion upon indigenous groups.

Nobody knows what kind of religious beliefs the Scythians had. Their belief might have been a more archaic stage than the Zoroastrian and Hindu systems, probably worshiping Agni (Tabiti/Atar), the fire deity of Indo-Aryans. Were they actually the ones who brought the Vedas to India? We might only speculate.

Nobody knows what kind of religious beliefs the Scythians had. Their belief might have been a more archaic stage than the Zoroastrian and Hindu systems, probably worshiping Agni (Tabiti/Atar), the fire deity of Indo-Aryans. Were they actually the ones who brought the Vedas to India? We might only speculate.

One last piece, proving that Scyths might have actually been Sakyas is to be found in the new development in Archeogenetics.

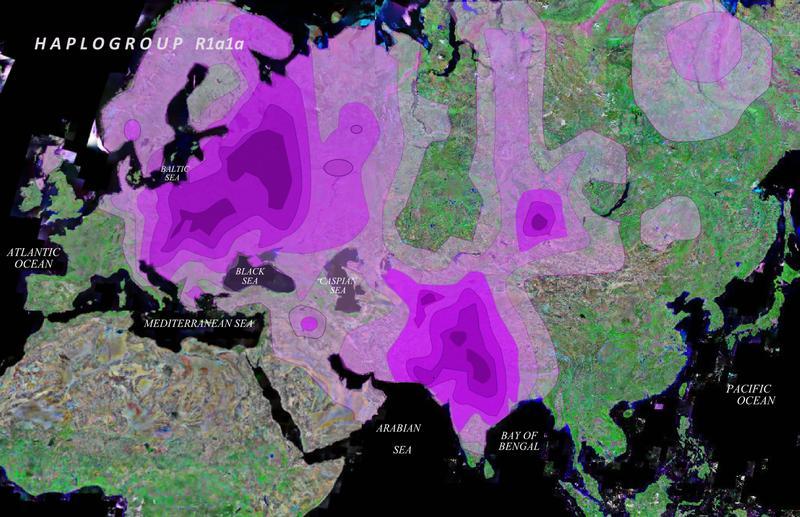

To prove the relationship between the Buddha’s tribe and the Slavic people let us focus on this new discipline of archeology. Firstly – according to Y chromosome (Y-DNA) testing a man’s patrilineal or direct father’s-line ancestry can be traced using the DNA on his Y chromosome (Y-DNA) through Y-STR testing. This is useful because the Y chromosome, like the patrilineal surname, is passed down unchanged from father to son. What is interesting to notice is the fact that Haplogroup R1a is the most frequently occurring Y-chromosome haplogroup in Central Europe (most noticeably in Slavic people) as well as in northern India, in those people who trace their ancestors back to an Aryan people (as shown on the picture).

The fact that it is the Slavic R1a haplogroup (especially the R1a1a subclass which is common to Poland as well as Indian and even 10 % of Sri Lankan people) and not R1b which characterizes people in Western Europe is worth mentioning. That would explain the two branches of the Indo-European language – satəm (R1a1 / Slavic) and centum (R1b / Western).

Secondly – as it was proven the haplogroup R1a1 is currently found in central and western Asia, Pakistan, India, and in Slavic populations of Eastern Europe, but it is rare in most countries of Western Europe. Investigations suggest that R1a1 gene expanded from the Dniepr-Don Valley, between 13 000 and 7600 years ago, and was linked to the reindeer hunters of the Ahrensburg culture that started from the Dniepr valley in Ukraine.

Ornella Semino proposes a postglacial spread of the R1a1 gene during the Late Glacial Maximum subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward. R1a1 is most prevalent in Poland, Russia, and Ukraine and is also observed in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Central Asia and India.

Recent genetic studies seem to confirm a west Eurasian origin for most of the Y-DNA haplogroup R1a1 likely linked to early Indo-European populations. Remains of the Andronovo culture horizon (strongly supposed to be culturally Indo-Iranian) of south Siberia were found to be 90 % of west Eurasian origin during the Bronze Age and associated almost exclusively with haplogroup R1a1 (and 77 % overall, in the bronze/Iron Age timeframe). The DNA testing also indicated a high prevalence of people with characteristics such as blue (or green) eyes, fair skin and light hair, implying even more an origin close to Europe for this population. Another marker that closely corresponds to Kurgan migrations is distribution of blood group B allele, mapped by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza. The distribution of blood group B allele in Europe matches the proposed map of Kurgan Culture, and Haplogroup R1a1 (YDNA) distribution.

What about Scythians DNA? Y-Chromosome DNA testing performed on ancient Scythian skeletons from the Krasnoyarsk region found that all but one of 11 subjects carried Y-DNA R1a1. Additional testing on the Xiongnu specimens revealed that the Scytho-Siberian skeleton (dated to the 5th century BCE) from the Sebÿstei site exhibited R1a1 haplogroup. Moreoever, the STR haplotype motifs characterising these R1a1 haplogroups were found to closely resemble those found amongst current Balto-Slavic populations in eastern Europe, as well as in indigenous populations in southern Siberia. In contrast, they were found only sporadically amongst central and east Asian populations, and not at all amongst western Europeans.

If that is the case, Polish people might identify with the historical Buddha in a much more materialistic ground, having the same forefathers as he had. If we assume that Scythians were actually Sarmatians (or Sarmatians were one more link might be added to the whole picture. The 15th-century Polish chronicler Jan Długosz was the first to connect the prehistory of Poland with Sarmatians, and the connection was taken up by other historians and chroniclers, such as Marcin Bielski, Marcin Kromer and Maciej Miechowita. Other Europeans depended for their view of Polish Sarmatism on Miechowita’s Tractatus de Duabus Sarmatiis, a work which provided a substantial source of information about the territories and peoples of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in a language of international currency. Sarmatism is treated in Poland as a form of legend, a myth, yet the new studies might prove that this myth might be true.

Nevertheless the peoples once known as the Scythians were amalgamated into the various Slavic groups of eastern and southeastern Europe.

Scholars and scientists might argue with this statement – yet a careful reader might wonder if the names like Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian – Saka – Sakya belong to different tribes or they are actually one and the same name of a single group of people? Maybe it is just a question of a different way of recording the proper name by outsiders. The Ockham’s razor puts it simply: “non sunt multiplicanda entia sine necessitate” – we should not create more, supposed entities if they are not needed, in this case five or more different tribes instead of one – especially with the recent development of DNA tracing and proof that they supply.

Finally I would like to point out briefly on the evidence in the early-Buddhist scriptures. In the Ambattha Sutta when it is referred to Gotama Sakyamuni (in such case this would actually mean „Scythian−sage”), that he „has blue eyes” [DN 3.144]. Furthermore the

Brahmins are described as „fair skinned, whereas the others (inferiors) are dark−skinned” [DN 3.81]. There probably was a color-conscious society in these times, and light or white skin was regarded as a nobler one. This strong attachment to pigment of the skin which Ambattha was referring to, gave the Buddha an opportunity to preach on the futility of feeling vanity regarding one’s caste and on the worth of morality and conduct. This paper does not propose to make any kind of superiority statements as Ambattha did. Actually we will never know exactly what Buddha’s eyes were – but knowing His teaching we can easily state that the color of the eyes is definitely not important for the liberation from suffering.

Research on Language

Having all the earlier suppositions in our minds – after the break-up of this original community of the common ancestors, perhaps some parts of their heritage remained in culture and beliefs, but most importantly and most profoundly in language and words.

Sometimes the words – being just designates of certain objects or experiences – are not the same in every Indo-European culture. I would like to take up and introduce just two very important words from the Buddhist perspective, being the most crucial for this system of belief – that is – “the Buddha” and “samaṇa”. These terms in Indian culture had a significant and deep tradition, and they are fundamental to Buddhist practice and modus operandi. What is astonishing is that the roots of these words can be traced in Polish, although not with such a particular usage.

In Prince Siddhartha’s times the ascetic tradition of samaṇas was developing quite fast, in opposition to the vedic and brāhmaṇical established order and point of view. The Buddha-to-be himself practiced some of these cruel and self-destructive practices of wandering ascetics for six years. Yet after his enlightenment and establishing the Saṃgha the Buddha did not differentiate and didn’t draw any external lines between “true” Buddhists and the rest of the samaṇas. What he did is he revalued the values, which means that in a Buddhist perspective a samaṇa would mean now just a monk, a recluse, a follower, a renunciate. It is interesting to notice that samaṇas and Brāhmaṇas are usually opposed, but Buddha re-evaluated these terms in such a way that they would only mean a truth-seeker, those individuals who want to liberate themselves from the round of rebirth, etc.

This kind of tradition is surely missing in Polish or even Slavic culture. Even in pre-Christian times there were no reports of a well established recluse tradition. The reason for it might be that the northern cold climate could not support a single man to supply himself during winter time. Maybe there were few, which we just don’t know of. Yet there is a link – it is a language connection – which acts as a designate that might give us an idea of what was meant by the Buddha. As the Blessed One revalued the values and names, so it actually is not about a chain of tradition that is important, but rather an ideal, a role-model, a perfect example of a holy life that the word designates or points to.

The word samaṇa might come from the P.I.E. root which can be found in Pokorny’s Proto-Indo-European Etymological Dictionary as “sem” [page 902-905].

“Sem” can mean “one”, “single” – which is acceptable for us as a samaṇa is alone, secluded from society he tries to discover the meaning of life by himself. In O.C.S. (Old Church Slavonic) the word samъ means “ipse, alone, single, sole, one; only one; one and the same “; in the Polish language we have a very clear word – “sam” – meaning the same as above O.C.S. – “alone, single, one”. The combinations which might describe or translate the word “samaṇa” could be “samotnik” the other one might be “szaman”. Samotnik means all the people who are living alone, who like solitude, but the meaning does not incorporate the seeking of truth or liberation or any spiritual search. If someone wants to describe such a person in the Polish language there is a word “pustelnik” derived from pusto – empty, uninhabited, void, deserted.

“Pusto” from root paus-

English meaning: to let go

[Material: Gk. παύω “make cease”, Med. “hear auf, lasse ab”, παῦλα “tranquility“, παυσωλή “rest”; O.Pruss. pausto “wild”, O.C.S. pustъ “ deserted, abandoned, forsaken, waste, desolate “; pustiti, Russ. рustítь, puskátь “(los)lassen”, Sloven. delo-pust “Feierabend” etc. maybe Alb. pushtoj “hug, not let go”, Alb.Gheg p(ë)shtoj, Alb. shpëtoj “escape, save, rescue”. Maybe Alb. bosh “empty” References: WP. II 1, Trautmann 208 f. Page(s): 790]

It is noteworthy that from this root we can derive many interesting words in Polish like “pustka” – emptiness, “puszcza” – wilderness, woodland, “puszczać” – to let go, unbinding “odpuszczać” – forgive, etc.

The third word could be “szaman” coming from “shaman” – which means witch doctor, healer, soothsayer, medium, elder, druid, magician [Late 17th century. Via Russian < Tungus šaman < Sanskrit śramanáḥ „Buddhist ascetic” < śrámas „religious exercise”]

To sum up – we might have three words describing and translating “samaṇa” –

1: Samotnik – loner, somebody who prefers to work or to be alone

2: Pustelnik – someone living in a secluded place, a spiritual ascetic,

3: Szaman – a healer, magician, witch doctor

Another origin of the word “samaṇa” could come from Sanskrit root “śram” (meaning to be tired of, to make effort in ascetic practice). This might suggest that the best one, adequate with the original meaning might be the word “pustelnik”. The method of translation I would like to use is – in this case – to leave an original word, inflecting it in cases, numbers etc in Polish and explaining the meaning of the word in the dictionary or footnote as a “pustelnik”. [The inflection example – see below.]

The general methods of translation I would like to use are as follows:

- Interpreting the meaning, rather than referring to the PIE root

1.A – translatable [example – citta & cetasika (umysł & właściwości umysłowe = mind & mental properties)

1.B – not translated [example – samaṇa (masculine gender in Polish), dhamma (feminine gender in Polish)]

- Generally referring to the PIE root or original word while still being correct with the meaning

2.A – clear and translatable [example – Buddha (Przebudzony = Awakened) Bhagava (Błogosławiony = Blessed One)]. The examples are explained below.

2.B – not translated and no clear PIE root while still understandable on intuitive level, neologisms [example – deva in Polish dewa (feminine gender in polish)]

- Using traditional way of commentary explanations and on compiled dictionaries and classifications.

The untranslated words, used in Polish in original form – like saman, dhamma, dewa – would use Polish grammar to inflect and being used later on in sentences. If the word ends with a consonant it usually means in Polish grammar that it is a masculine gender (saman). When a word ends with vowel it will be perceived as a feminine gender (dhamma).

Declension of saman (m) & dhamma (f):

| singular | plural | |

| Nominative: |

Mianownik:samaṇoPOL: saman (m)

POL: dhamma (f)samaṇāPOL: samani, samanowie

POL: dhammyAccusative:

Biernik:samaṇaṁPOL: samana

POL: dhammęsamaṇePOL: samanów

POL: dhammyInstrumental:

Narzędnik:samaṇenaPOL: samanem

POL: dhammąsamaṇehi, samaṇebhiPOL: samanami

POL: dhammamiAblative:Ablatyw:samaṇasmā, samaṇamhā, samaṇāPOL: samana

POL: dhammysamaṇehi, samaṇebhiPOL: samanów

POL: dhammDative:

Celownik:samaṇassa, samaṇāyaPOL: samanowi

POL dhammiesamaṇānaṁPOL: samanom

POL: dhammomGenitive:Dopełniacz:samaṇassaPOL: samana

POL: dhammysamaṇānaṁPOL: samanów

POL: dhammLocative:Miejscownik:samaṇasmiṁ, samaṇamhiPOL: samanie

POL: dhammiesamaṇesuPOL: samanach

POL: dhammachVocative:Wołacz:samaṇaPOL: saman

POL: dhammasamaṇāPOL: samani, samanowie

POL: dhammy

Much more profound is the word Buddha – although it does not refer to any tradition in Slavic culture of Enlightened ideals – it designates to an understandable root. The Awakened One in the Polish language is Przebudzony, where budzić is “to awake”, “being conscious”, or “to stop dreaming”. It is quite interesting to see more of the meanings that this Indo-European root has, so let us investigate it by quoting Pokorny’s dictionary:

“Budzić” from root bheudh-, nasal bhu-n-dh-

English meaning: to be awake, aware

Material: Themat. present in O.Ind. bṓ dhati, bṓ dhate “ awakened, awakens, is awake, notices, becomes aware“, Av. baoδaiti “ perceives “, with paitī- “ whereupon direct one’s attention “ (= Gk. πεύθομαι, Gmc. *biuðan, O.Bulg. bljudǫ); Aor. O.Ind. bhudánta (= ἐπύθοντο), perf. bubṓ dha, bubudhimá (: Gmc. *bauð, *buðum), participle buddhá- “awakened, wise; recognized “ (== Gk. ἀ-πυστος “ignorant; unfamiliar”); maybe Alb. (*bubudhimá) bubullimë “thunder (*hear?)” [common Alb. : Lat. dh > ll shift]. O.Ind. buddhí- f. “understanding, mind, opinion, intention “ (= Av. paiti-busti- f. “noticing”, Gk. πύστις “investigating, questions; knowledge, tidings “); causative in O.Ind. bōdhá yati “ awakens; teaches, informs “, Av. baoδayeiti “ perceives, feels” (= O.Bulg. buždǫ , buditi, Lith. pasibaudyti); of state verb in O.Ind. budhyátē “ awakes, becomes aware; recognizes “, Av. buiδyeiti “becomes aware”, frabuidyamnō “awakening”; O.Ind. boddhár- m. “ connoisseur, expert “ ( : Gk. πευστήρ-ιος “ questioning “); Av. baoδah- n. “ awareness, perceptivity “, adj. “ perceiving “ (: Hom. ἀ-πευθής “ unexplored, unacquainted; ignorant”);

Gk. πεύθομαι and πυνθάνομαι (: Lith. bundù, O.Ir. ad-bond-) “ to learn; to find out, perceive, watch” (πεύσομαι, ἐπυθόμην, πέπυσμαι), πευθώ “knowledge, tidings “; (…)

Proto-Slavic form: pytati: O.C.S.: pytati “examine, scrutinize” [verb], Russian: pytát” “torture, torment, try for” [verb], Slovak: pytat” “ask” [verb], Polish: pytać “ask” [verb], Serbo-Croatian: pítati “ask” [verb], Slovene: pítati “ask” [verb], Other cognates: Lat. putüre “cut offbranches, estimate, consider, think” [verb].

Note:

From Root bheudh-, nasal. bhu-n-dh- : “to be awake, aware” derived Root peu-1, peu̯ǝ- : pū̆ – : “to clean, sift” , Root peu-2 : “to research, to understand” (see below).

Lith. bundù, bùsti “wake up, arouse” and (without nasal infix) budù, bude ́ti “watch”,

bùdinu, -inti “waken, arouse, revive”, budrùs “watchful, wakeful”; causative baudžiù , baũsti “punish, curse, chastise, castigate “; refl. “intend, mean, aim” (*bhoudh-i̯ō), baũdžiava ‘socage, compulsory labour “, Lith. bauslỹs “command, order”, Ltv. baũslis “ command “, Ltv. bauma, baũme “rumor, defamation “ (*bhoudh-m-), Lith. pasibaudyti “ rise, stand up, sally “, baudìnti “ to cheer up, liven up; ginger up, encourage, arouse, awaken one’s lust “, O.Pruss. etbaudints “ to raise from the dead, reawaken “. Themat. present in O.Bulg. bljudǫ, bljusti “look after; protect, beware, look out”, Russ. bljudú, bljustí “observe, notice” (about Slav. -ju from IE eu s. Meillet Slave commun2 58).(…)

Causative in O.Bulg. buždǫ, buditi “waken, arouse, revive”, Russ. bužú, budítь ds. (etc; also in Russ. búdenь “workday”, probably eig. “working day “ or “day for corvée “); stative verb with ē-suffix in O.Bulg. bъždǫ , bъděti “watch”, perfective (with ne-/no- suffix as in Gk. πυνθ-άνο-μαι, wo -ανο- from -n̥no-, Schwyzer Gk. I 700) vъz-bъnǫ “awake” (*bhud-no-, shaped from Aor. of type Gk. ἐπύθετο, etc, s. Berneker 106 f.;

Maybe truncated Alb. (*zbudzić) zgjoj “awaken”: O.C.S.: ubuditi “awaken” [verb]; vъzbuditi “awaken” [verb]; phonetically equal Alb. -gj- : Pol. -dzi- sounds budzić “awaken, arouse” [verb], perf. zbudzić “awaken, arouse”. Russ. bódryj “alert, awake, smart, strong, fresh”,Ser.-Cr. bàdar “agile, lively”.

References: WP. II 147 f., Feist 41, 97, Meillet Slave commun2 202 f.

Page(s): 150-152

Apparently the root and words derived from it were used in various ways, but the meaning preserved in almost every IE language. Same method as with Przebudzony (Awakened), could be used to translate the word Bhagava:

“Być” from root bheu-, bheu̯ǝ- (bhu̯ā-, bhu̯ē-) : bhō̆ u- : bhū-

English meaning: to be; to grow

(…)O.Ind. bhū́ ti-ḥ, bhūtí-ḥ f. “being, well-being, good condition, prospering; flourishing “ (Av.

būti- m. “name daēva”? = O.C.S. za-, po-, prě-bytь, Russ. bytь, Inf. O.C.S. byti, Lith. bū́ ti; with ŭ Gk. φύσις).

The English translation for Bhagava is Blessed One, almost the same meaning in Polish as the word “Błogosławiony” – “famous for his good condition, blessed one”.

As mentioned in the beginning, the reason for introducing Buddhism to Polish society, especially the early suttas is to give a free and independent outlook on reality. Throughout the Pāḷi Tipiṭaka there is an emphasis on discovering the truth – introduced as Four Noble Truths as well as the Eightfold Noble Path. This requires the introduction or revaluation of some very important principles and values in life – like renunciation or strong determination. Since some Pāḷi words will be introduced in their original sound, (for example danā – “to give” in Polish “dawać, coś co jest dane”) the given explanations, compiled dictionaries and call for intuitive cognition of some words might spark some light and ignite feelings of brilliance and admiration for the 2500 year old Buddhist tradition.

Future studies

This work is written down just for the purpose of defining the field of research that I would like to engage in my future studies. There might be (and there probably are) some mistakes and misconceptions which of course through time I would like to correct. Right now I would just like to show some major similarities between two languages: Polish language and Pāḷi language.

First of all – I would like to concentrate only on Pāḷi – Polish similarities, avoiding at this stage any engagement into Sanskrit language – which would have been a natural link between Polish and Pāḷi – because of my lack of proficiency in this language on one hand and concise character of this work on the other. With time including Sanskrit might be essential to explain some difficult issues.

Next I would like to compare some interesting examples from Pāḷi words and match them with Polish words which sound the same and have the same meaning. Later – it would be beneficial to link two grammars. Finally it would be necessary to give some examples of translated suttas in this way.

The work is just at the beginning stage. However the Polish people might perceive Buddhist teaching as being not so exotic anymore (exo, outside – meaning foreign, bizarre, alien). As a Buddhist missionary monk, native Polish, that is my genuine and sincere intention.

Sources and links:

| Haplogroups:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_R1b_%28Y-DNA%29 |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_R1a_(Y-DNA)

Kurgan hypothesis:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan_hypothesis

Kurgan building tradition is alive in Poland. The Polish word for kurgan is kopiec or kurhan. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan#In_Poland

Sakas, Scythians, etc search:

Sutta translations to english:

Thanissaro Bhikkhu – http://www.accesstoinsight.org/Bibliography:

- Julius Pokorny: “Proto-Indo-European Etymological Dictionary”

- Rollo May: “Man’s search for himself”

- Carl Rogers: “Freedom to learn

- Microsoft® Encarta® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation.

- Grzegorz Jagodziński: “Gramatyka polska”

- Szemerényi, Oswald: „Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian; Skudra; Sogdian; Saka“

- Patrick Geary: “The Myth of Nations.”

Sigiriya (Lwia Skała) – V wiek n.e.

Dla Cejlończyków miejsce historyczne, związane z ich władcami, żyjącymi tu ponad 1500 lat temu. Świetny punkt widokowy na całą okolicę i niedostępną dżunglę, a dla każdego turysty niebywały kunszt starożytnych rzeźbiarzy i malarzy.

Skała mieszcząca onegdaj płac i fortyfikacje królewskie wraz z potężnymi przyległościami, ogrodami i haremem  Cesarskie tarasy, potężny harlem, sale tronowe, malowidła naskalne, nie naruszone od wieków przez siły natury – królewska zachcianka sprzed tysiącleci zdumiewa lokalizacją i rozmachem wykonania.

Cesarskie tarasy, potężny harlem, sale tronowe, malowidła naskalne, nie naruszone od wieków przez siły natury – królewska zachcianka sprzed tysiącleci zdumiewa lokalizacją i rozmachem wykonania.

Appendix

Pronounciation of polish language.

Vowels

l a is pronounced like u in us

l e is pronounced like e in fed

l i is pronounced like i in is

l o is pronounced like o in won

l u is pronounced like u in put

l y is pronounced like i in this

Polish vovels

l ą is pronounced like ou in mountain

l ę is pronounced like en in spend (silent n)

l ó is pronounced like u in put

Consonants

l g is pronounced like g in get

l k is pronounced like k in cat

l j is pronounced like y in yen

l n is pronounced like n in nut

l p is pronounced like p in put

l b is pronounced like b in but

l m is pronounced like m in mine

l v & w is pronounced like v in video

l r is pronounced like r in rail (with r sound)

l l is pronounced like l in lobby

l c is pronounced like tz in horovitz

l t is pronounced like t in put

l d is pronounced like d in dam

Polish consonants and clusters

l ć is pronounced like ch in cheese

l ł is pronounced like w in wait

l ń is pronounced like ñ in spanish señor

l ś is pronounced like ś in sanskrit śiva

l ż is pronounced like g in french „bon voyage”

l ź is pronounced like g in mirages (without hard sound) [burm. – y in yue]

l cz is pronounced like ch in chariot

l dzi is pronounced like ji in fiji

l dź is pronounced like g in fuge [pali – jj in vijja]

l dż is pronounced like j in jam

l sz is pronounced like sh in show

l ch is pronounced like h in hut

l rz is pronounced like g in french „bon voyage”

♦

Sigriya – Lwie Pazury

| Pāḷi root / + meaning | Polish word | Polish meaning |

|

Łapać | To grab |

|

Jest | To be |

|

Jeść | To eat |

|

Banda | Gang, close group of people |

|

1. Objaśniać |

2. jasny1. To speak clearly 2. clear, bright

- √ Bhar / + to bear, to support

BraćTo take, to

- √ Bhī + to fear

Bać, BojęAfraid, to fear

- √ Bhid / + to brake,

Rozbić, rozbityTear apart, broken

- √ Bhū / + to be

Być, bytTo be, being10. √ Bhū / + to developBudowaćTo build11. √ Bhuj / + to eat, to enjoyBuziaface, mouth

- √ Budh / + to awake, to understand

BudziWake, to wake, awaken13. √ Chad / + to cover up1. Cień

2. Czad

3. Czarny1. Shadow

2. Smoke (carbon monoxide)

3. Black14. √Chid √ Kat / + to cutCiąćTo cut

- √ Cur / + to steal

KraśćTo steal

- √ Dā / + to give

DawaćTo give

- √ Ḍas / + to bite

DziąsłoGum (part of mouth)

- √ Dham / + to blow

Dmie, dmuchaćTo blow (for wind, air)19. √ Dhar / + to bear, to holddzierżyćTo hold

- √ Dis / + to see

dostrzecTo spot

- √ Duh / + to milk

doićTo milk

- √ Gad / + to say

GadaćTo talk, to say23. √ Gam / + to gogonićChase, run24. √ Garah / + to disgracegardzićTo despise25. √ Ghus / + to shoutGłośno, głosNoisy, voice26. √ Han / + to strike, to killHarataćTo injure, to wound27. √ Hve / + to call upon, to evokeChwalić / chwałaTo praise / glory

- √ I / + to go

IśćTo go29. √ Jan / + to born, to produce, to ariseRodzić, rodzinaTo born, a family

- √ Jīv/ + to live

żyćTo live (opposite to death)

- √ Jut / + to shine

Jutrznia, jutroDawn, tomorrow32. √ Kal / + to sound, to countkalkulowaćTo calculate33. √ Kas / + to ploughKosi, kosiarzTo cut (grass, crops), plough (plow through – „plow the high seas”), ploughman34. √ Kās / + to coughKasłaćTo cough35. √ Kās / + to shinepokazaćTo show36. √ Kar / + to work, to makeharowaćTo work hard,

to slave

- √ Kī / + to buy

Kupić, kupowaćTo buy

- √ Lā / + to flee, run away

płoszyćTo frighten away39. √ Lal / + to playlalkaA doll40. √ Lap / + to speakpaplaćTo talk vainly, idly41. √ Lih / + to licklizaćTo lick42. √ Lip / + to smearlepkiTo sticky43. √ Lup / + to cut off, to plunder1. Łup

2. łupać1. loot

2. crack44. √ Mā / + to measureMierzyć, miaraTo measure,

the length

- √ Madd / + to press, to crush

MiażdżyćTo crush, to press46. √ Mar / + to die1. Umierać, martwy

2. Mara senna

3. Marzanna1. To die, dead

2. Nightmare

3. goddess, symbol of winter/death

- √ Math / + to churn, to stir

MieszaćTo stir

- √ Manth / + to churn,

MasłoButter49. √ Mas / + to touchmuskać1. To touch delicately

- √ Mih / + to water,

MoczyćTo water, wet51. √ Mi / + to measuremierzyćTo measure52. √ Miss / + to mixmieszaćTo stir, to mix53. √ Muc / + to be freeMoc, móc, możliwyPower, to be able to

- √ Ña / + to know

1. znać

2. nauka1. To know

2. knowledge55. √ Nas / + to vanishznikaćTo vanish, disappear

- √ Nacc √ Naṭ / + to see

taniec, tany, tańczyćA dance, to dance57. √ Nud / + to remove, to avertnudnośćNausea, boredom

- √ Pā / + to drink

1. Pić, poić

2. piwo1. To drink, to quench thirst

2. beer59. √ Pac / + to cook1. Piec,

2. paciaja1. To cook,

to burn up, a stove

2. over boiled

- √ Pass / + to look

PatrzećTo look, to see61. √ Pat / + to fallPadaćTo fall62. √ Pih / + to desirePycha, pyszny,1. Pride, proud, boast about sth.

2. delicious63. √ Plu / + to float, to springPływać, pluskaćTo float, to splash64. √ Pucch / + to questionPytaćTo ask question65. √ Ram / + to take delight inRadośćhappiness66. √ Rud / + to cry, to weep1. Marudzić

2. Ryczeć1. To whine, to grumble

2. to blubber, to roar67. √ Rudh / + to hinderTrudzić, trudnośćTo toil, difficulty

- √ Ruh / + to grow up

1. Rosnąć

2. Ruch1. To grow

2. movement

- √ Sad / + to sit

Siedzieć, siadTo sit

- √ Sev / + to serve, to associate

Służyć, serwować, (zob: serb)To serve

- √ Si / + to lie down

1. posłanie

2. słaniać1. Bedding

2. to stagger72. √ Siv / + to sewSzyć, szewTo sew, a seam73. √ Sīd , √ Sad / + to sink downOsad, osadzaćSettle, precipitate

- √ Su / + to listen

SłuchaćTo listen75. √ Su / + to trickle awayStruga, sączyćStream, to sip

- √ Suc / + to grieve

SmucićTo be sad

- √ Sup / + to sleep

SpaćTo sleep

- √ Sus / + to dry

SuszyćTo dry

- √ Svad √ Sā / + to taste

SmakowaćTo taste80. √ Tacch / + to cutCiąćTo cut81. √ Tas / + to be afraidtrząśćTo shake82. √ Ta / + to heatciepłoThe heat83. √ Tā / + to protect, to secureczaićTo wait in safety

- √ Tha / + to stand

StaćTo stand

- √ Vas / + to dwell

1. Wieść, wiek

2. wiosna

3. wieś1. To lead [a life], age, period of time

2. spring

3. country, village

- √ Vad / + to say

1. opowiada, powiada

2. mowa, mówić

3. rozwodzić się nad czymś1. to talk about, to tell (story)

2. to say, to speak

3. to speak long time87. √ Veṭh / + to coilWstęga, zwijać, owijaćRibbon, band, to coil

- √ Yaj / + to make oblation, to give

JałmużnaAlms, charity89. √ Yuj / + to yokeJarzmo, jarzmićA yoke, to yoke

♦

Sigiriya – Malowidła naskalne

| Pāḷi word / + meaning | Polish word | Polish meaning |

| ABHILEPANAM / smeared | LEPKI | sticky |

| ABHIRADHETI / content, satisfy | RADY, RADOWAĆ | content, happy, to be happy |

| ACCHARIYO / wonderful, astonished | CZARUJĄCY, CZARY | magical, wonderful, magic |

| ACARIYO / teacher | NAUCZYCIEL | teacher |

| ACCHI / eye | OCZY | eyes |

| ADDO / wet, moist | WODA | water |

| ADO / eating, feeding | JEDZENIE | Food, eating |

| AGGI / AGGINI fire | OGIEŃ | fire |

| AKKHAM / organ of eye | OKO / OCZY | eye / eyes |

| ANDHABALO / stupid | DEBIL | stupid |

| ANHO / day | DZIEŃ | day |

| ANI / not | NIE / ANI | no / neither |

| ANNA / other | INNA | other |

| APPEVA / perhaps | NA PEWNO / PEWNOŚĆ | be sure / sure |

| APPA-BHOGATTAM / poverty | BOGATY | rich |

| ARAMO / monastery | EREMITA | Recluse (rus.) |

| ASAMO / uneven, unequal | TO SAMO | the same |

| ASESO / all, every | WSZYSCY | all, everybody |

| ATTHA, ASITI / 8, 80 | OSIEM / OSIEMDZIESIĄT | 8, 80 |

| ATITHOKO / very little | TYLKO | only, just |

| BALA / military force, fight | WOJSKO, WALKA | Army, fight |

| BELUVO / vilvatree | BIAŁY | white ? |

| BHAGAM / BHAGAVA majesty, power, love | BÓG | god |

| BHAGINI / devout lady | BOGINI | goddess, lady god |

| BHANDATI / quarell, abuse | BANDYTA | bandit |

| BHARO / burden, load | BARY, BARKI | shoulders |

| BHATA / brother | BRAT | brother |

| BHAYAM / fear | BAĆ / BOJĘ | To fear / afraid |

| BHOGO / enjoying | BŁOGI | bliss |

| BHAVITO/ occupied with | BAWIĆ | 1. entertain 2. stay |

| BHEDAKO / one who breaksBHEDO / breaking, rending | BIEDAKBIEDA | poor manpoorness |

| BHUMI / earth | ZIEMIA | earth |

| BRAHMA / gods name | BRAMA | gate ? |

| BRAVITI / BRUTI / say, tell, call | BREDZIĆ | talk nonsense, to rave |

| BUBBULA / bubble | BĄBEL | bubble |

| CATTARO, CATTANSAM / 4 , 40 | CZTERY, CZTERDZIEŚCI | 4, 40 |

| CHA, SATTHI / 6, 60 | SZEŚĆ, SZEŚĆDZIESIĄT | 6, 60 |

| CHAMA / earth | ZIEMIA | earth |

| CHAYA / shadow | CIEŃ | shadow |

| CIRAM / bark, fibre | KORA | Bark |

| CUCUKAM / nipple | CYCKI | breasts |

| CULA / top-knot of hair on the head | KULA, CZUB | Ball, sphere, round shape |

| DADATI , DETI , DAYATI / give | DAĆ/ DAWAĆ/ DAJ | To give / giving / give |

| DALETI / split | DZIELIĆ | To split |

| DANAM / givings | DANINA | Tribute / gift |

| DARU / wood | DRZEWO | tree |

| DASA / 10 | DZIESIĘĆ | 10 |

| DASSIYATI / to be shown | DOSTRZEGAĆ | to spot |

| DHUMO / smoke | DYM | smoke |

| DAUSARO / grey | SZARY | grey |

| DHIGHAKO, DHIGO / long | DŁUGO / DŁUGI | long |

| DHITIKA / daughter | DZIEWCZYNKA, DZIECKO | Girl, child |

| DIVA, DIVASO / by day | DZIEŃ | day |

| DIVOKO / deva | DZIW | old word for a deity |

| DOHATI / to milk | DOIĆ | To milk |

| DUSETI / to injure | DUSIĆ | strangle |

| DUVARAM, DVARAM / door | DRZWI | door |

| DVE, DVADASA / 2, 20 | DWA, DWADZIEŚCIA | 2, 20 |

| DVIKAM / two, a pair | DWÓJKA | Pair of two |

| EKAM / 1 | JEDEN | 1 |

| ESAKO / seeking | SZUKAĆ | To seek |

| ETHRAHI / now | TERAZ | now |

| GABHIRO / deepGAMBHIRATA / depth | GŁĘBOKOGŁĘBIA | Deepdepth |

| GABATI speak | GADAĆ, GĘBA | Speak, mouth |

| GAHO / house | GMACH | Big house |

| GALO / throat | GARDŁO | throat |

| GARULA / garuda bird | ORZEŁ | eagle |

| GAVI , GO / cow | KROWA | cow |

| GHOSETI / shout, proclaim | GŁOSIĆ | proclaim |

| GIRI / mountain | GÓRA | mountain |

| GIVA / neck | GRZYWA | mane |

| GULA / pock, pimple | GULA | boil |

| HAMSO / goose | GĘŚ | goose |

| HASO / happy | HASAĆ | Sporting, jesting, mirth, joy |

| HIMO / cold | ZIMNO | cold |

| ISA / axis | OŚ | axis |

| JAMBU / apple | JABŁOŃ | Apple tree |

| JANGALO / jungle | DŻUNGLA | jungle |

| JANI / wife | ŻONA | wife |

| JARA / old age | JARY | old word for young |

| JAVO / speed | ŻYWO | speedy |

| JIVITAM, JIVATI, JIVI, JIVO / alive | ŻYWY, ŻYĆ, ŻYCIE | Alive, live, life |

| JIYA / bow string | ŻYŁA | String, vein |

| KABALO / a morsel, lump | KAWAŁEK | A morsel, lump |

| KADA / when | KIEDY | when |

| KAKI, KAKO / hen crow | KRUK | crow |

| KAPPATO / tattered cloaths , rags | KAPOTA | Old jacket |

| KARA / jail | KARA | punishment |

| KARETI / to cause to be done | KAZAĆ | To order, to tell sb to do sth |

| KAROTI / basin, bowl, skull | 1. CZERPAK 2. CZEREP | 1. bowl 2. top of the head, skull |

| KASO / cough | KASŁAĆ, KASZEL | cough |

| KASMIRO / cashmere | KASZMIR | cashmere |

| KATAMO, KATARO / what which | KTÓRY | which |

| KATTHA wherein | DOKĄD | wherein |

| KATU , KATU / sacrifice , sharp | KAT, KATOWAĆ | Executioner, torment, torture |

| KAVATAKO / the panels of the door | KOŁATKA, KOŁATAĆ | Knocker, rattle |

| KO / who | KTO | who |

| KOKILA / cuckoo | KUKUŁKA | cuckoo |

| KHUDDO / poor, small | CHUDY | thin |

| KHUDITO / hungry | GŁODNY | hungry |

| KUKKUTO / cock | KOGUT | cock |

| KULA / family, clan | KLAN | Family, clan |

| KUMBHO / water pot, pitcher | KUBEŁ | bucket |

| KUNCIKA / key | KLUCZ | key |

| LEKHA / line | LINA | line |

| LEKHO / letter | LIST | letter |

| LOBHO, LUBBHATI / craving, greedy | LUBIĆ | To like, to please |

| MADHU / honey | MIÓD | honey |

| MAKAKA / monkey | MAŁPA | monkey |

| MAKASA / mosquito | MUCHA, MUSZKA | fly |

| MAKKHESI / smeared, anointed | MAŚĆ | ointment |

| MAMAKO / mine | MOJE | mine |

| MAMSAM / meat | MIĘSO | meat |

| MANNATI / think, imagine | MARZYĆ, MAJAKI | Imagine, illusion |

| MASO, MASAM / month | MIESIĄC | month |

| MATA, MAMA / mother | MATKA, MAMA | Mother, mum |

| MASATI / touch | MUSKAĆ | Subtle touch |

| MAYAM / we | MY | we |

| ME / me | MNIE | me |

| MEGHA / cloud | MGŁA, MGŁAWICA | Mist, fog, cloud |

| MILAKKHO / barbarian | MLEKO | (milk ?) |

| MUSIKO / mouse | MYSZ | mouse |

| MUCCATI / be free to do, released, urine |

|

|

| NA / no | NIE | no |

| NABHO / sky | NIEBO | Sky, heaven |

| NADATI / to sound | NADĘTY, DĄĆ | To blow, to sound |

| NAGARAM / a town with market | GRÓD, GRODZIĆ | City, fence, mark |

| NAGGO / naked | NAGI, NAGO | naked |

| NAMA /NAMAM name | IMIĘ | name |

| NANA / different | INNE | Different, other |

| NANAM / knowledge | ZNAĆ, ZNANIE | To know, knowing |

| NASA / NASIKA nose | NOS | nose |

| NATANAM / dancing | TANY, TAŃCZYĆ | Dance, dancing |

| NISA / night | NOC | night |

| NAVAKO / NAVO new | NOWY | new |

| NIGADATI / tell, delare, recite | GADAĆ | To talk |

| NIGGHOSO / noise | GŁOŚNO | Loud, noise |

| NINNO / deep, lowlying | NIZINA, NISKO | Valley, low-lying |

| NIRODHO / not born | NIE RODZIĆ | Not born |

| NISA / night | NOC | night |

| NO / not | NIE | no |

| NUDATI / reject, avert | NUDNOŚCINUDNO | Nauseabored |

| OPATITO / fallen down | OPADAĆ | Fall down |

| OSADETI / to sink, to depressOSIDATI / sinking | OSADZAĆ, OSIADAĆ | To settle, to sink |

| PACCHA / afterwards | PÓŹNIEJ | Later, afterwards |

| PAHARATI / strike, hurt | POHARATAĆ | to cut |

| PAJJALATI / burn, blaze | PALIĆ | To burn |

| PAKKHI, PATANTO, PATANGO / bird | PTAK | bird |

| PALAPITAM / idle talk | PAPLAĆ, PAPLANINA | Idle talk |

| PALAYATI / run away, flee | PŁOSZYĆ | Frighten away |

| PAMSU / dirt | PIASEK, PIACH | sand |

| PANCA, PANNASAM / 5, 50 | PIĘĆ PIĘĆDZIESIĄT | 5, 50 |

| PANDITAKO / pedant | PEDANT | pedant |

| PANHO / question | PYTANIE | question |

| PARIVATTO / change | PRZEWRÓT, PRZEWRÓCIĆ | turn over |

| PASADO / mansion | POSADA | mansion |

| PASO / string | PASEK | Belt, string |

| PATTO / bowl | PATELNIA | frying pan |

| PAVADATI / speak out | POWIEDZIEĆ | Say, speak out |

| PAVAT / diffuse a scent | POWĄCHAĆ, WOŃ | To smell, scent |

| PAYAKO / one who drinks | PIJAK | drunkard |

| PESETI / send | POSYŁAĆ, SŁAĆ | To send |

| PHALAM / fruit | PŁODY | Fruits, produce |

| PHENAM / foam | PIANA | Foam, froth |

| PILETI / oppress, haras | PILIĆ | to urge |

| PLAVATI, PILUVATI / float | PŁYWAĆ, PŁAW | To swim, float |

| PUCCHAT / ask | PYTAĆ | Ask question |

| PUNNO / full | PEŁNO | full |

| RACCHA / road | DROGA | road |

| RAKKHA / protect |

|

1. Hand, guarantee2. protect |

| RAVA / noise | WRZAWA | noise |

| RATI / pleasure, love | RAD, RADOŚĆ | Satisfied, happiness |

| RODATI / weep, wail | RYCZEĆ | Blubber, roar |

| ROHITA / red | KREW | blood |

| RUHATI / ascend | RUCH | move |

| SA (sanskr. SVA) / one`s own | SWÓJ | one`s own |

| SADA / ever, always | WSZĘDZIE, WSZYSTKO | Everywhere, all |

| SAKKHARA / sugar | CUKIER | sugar |

| SALA / hall | SALA | hall |

| SAMANO / recluse | SZAMAN | Recluse, medicine man |

| SAMO / same | SAMO | The same |

| SANKU / stump, stake | SĘK | Knot (in wood) |

| SANNA / SANNI imagining | SEN | dream |

| SANTO / saint | ŚWIĘTY | saint |

| SARADO / year | ROK | year |

| SARANGO / deer | SARNA | deer |

| SASI / moon | KSIĘŻYC | moon |

| SASO / a hare | 1. ZAJĄC,2. SUS |

2. Leap |

| SASSU / father-in-law | ŚWIEKRA | Father in law |

| SATAM / 100 | STO | 100 |

| SATO / joyful | SZCZĘŚCIE | happiness |

| SATTA , SATTATI / 7, 70 | SIEDEM, SIEDEMDZIESIĄT | 7, 70 |

| SATTHI / 60 | SZEŚĆDZIESIĄT | 60 |

| SATTI / knife | SZTYLET | Knife, dagger |

| SAYANA / SENAM sleeping | SPAĆ, SENNY | Sleep, sleepy |

| SETO / white | ŚWIATŁO | light |

| SIBBANI / sew | SZYĆ | sew |

| SIGALO / jackal | SZAKAL | jackal |

| SIGHO / quick | SZYBKO | quick |

| SIKHA / peak | SZCZYT | peak |

| SILABBATAM / religious rites | ŚLUBY | Holy orders, to pledge |

| SIVATHIKA / charnel – house | ŚWIĄTYNIA | sacred place |

| SUKKHO / dry | SUCHY | dry |

| SUNU / son, child | SYN | son |

| SUPATI / sleep | SPAĆ | sleep |

| SUPO / soup | ZUPA | soup |

| SUSSUTE / to be heard | SŁYSZANY | To be heard |

| TAD / since, from | ODTĄD, STĄD | Since, from here |

| TALA / surface | TŁO | background |

| TAHAM / there | TAM | there |

| TAMO / dark | CIEMNO | dark |

| TANU / thin | CIENKI | thin |

| TANTA / string | STRUNA | string |

| TAPO / heat | CIEPŁO | heat |

| TARAKA / star, the pupil of the eye | ŹRENICA | Pupil of the eye |

| TARAVO / tree | TRAWA | grass |

| TASATI / tremble | TRZĄŚĆ | Tremble, shake |

| TATHA / thus | TAK, TAKOŚĆ | Thus, |

| TE, TVAM / thee, you | TY, TWOJE | You, yours |

| TINI , TIMSAM / 3, 30 | TRZY, TRZYDZIEŚCI | 3, 30 |

| THOKO / small, slight | TYLKO, TROCHĘ | Small, only, not much |

| TUCCHA / empty, vain | CZCZA [GADANINA] | Empty, vain [talk] |

| TVAM, TUVAM / thou | TY | you |

| UBHAYO / both | OBOJE | both |

| UDDA / otter | WYDRA | otter |

| UGGA / huge | OGROMNY | huge |

| UPPAJJATI / arise, appear | POJAWIAĆ | To appear |

| VACAKO, VATTI, VADATI / speaking | WOKAL, WODZIĆ, MÓWIĆ | Voice, to talk |

| VAHATI / bearing, carrying | WZIĄĆ | To take, to |

| VAKA / wolf | WILK | wolf |

| VANA / wound | RANA | wound |

| VARAHA / hog, boar, pig | WARCHOŁ | Hog, boar, pig |

| VASANTO / spring | WIOSNA | spring |

| VASO / perfume | WĄCHAĆ, WĘCH | To smell |

| VATI, VAYATI / blow | WIAĆ | To blow |

| VAYO / any period of life | WIEK | age |

| VAYU / wind | WIATR | wind |

| VEJJA / physician, doctor | WIEDŹMA | witch |

| VIDHATI, VIDALETI / assign, break, split | WYDZIELAĆ | To split |

| VIDATI / know | WIEDZIEĆ | To know |

| VIDHAVA / widow | WDOWA | widow |

| VIJAYO / victory | ZWYCIĘŻAĆ | To win |

| VIVADO / dispute | WYWÓD | argument |

| VIVARATI / open the door | WYWAŻAĆ | To force the door |

| VO / yours | WASZ | Yours (plural) |

| YATHA, YO / as, like | JAK | As, like |

| YUGO / yoke | JARZMO | yoke |

| YUVIN / young | JUNAK | Young man |

♦

Widok z Sigiriya

| Pāḷi word | Russian/Ukrainian word |

| akkhi | око |

| aggi | огонь |

| ajo | козёл |

| añña | иной |

| aṭṭha | восемь |

| ati | очень |

| adanaṃ | еда |

| adeti | ест |

| antare | внутри |

| alasa | ленивый |

| alla | влажный |

| asman | камень |

| asmi | есмь |

| assāda | услада |

| asso | лошадь |

| aha | я |

| ācariyo | учитель |

| icchati | хочет |

| ida | здесь |

| iva | ибо |

| īsā | ось |

| ugga | огромный |

| uccaṃ | выше |

| udakaṃ | вода |

| udaraṃ | утроба |

| udda | выдра |

| upa- | по-, под- |

| ubho | оба |

| eka | экий |

| etad | этот |

| eti | идет |

| esati | ищет |

| kadā | когда |

| katara | который |

| kabalo | кавалок (украинский) |

| karoṭi | череп |

| kalasaṃ | кружка |

| kāso | кашель |

| kikī | курка (украинский) |

| kili | клик, щелк |

| ko | кто |

| kokila | кукушка |

| kumbho | кувшин |

| kula | клан |

| kusala | искусный |

| kūṭa | кут (украинский) |

| gaṇhāti | грабастает |

| garu | грузный |

| garuḷa | орёл |

| galo | горло |

| gāma | громада |

| giri | гора |

| gīvā | грива |

| guḷo | гуля (украинский) |

| go | корова |

| ghammo | жара |

| cattāro | четыре |

| cando | сандал |

| cīraṃ | кора |

| cūḷā | чуб |

| ceteti | учитывает |

| cha | шесть |

| chavi | шкура |

| chāyā | тень |

| jambu | яблоня |

| jānana | знание |

| jānāti | знает |

| jāni | жена |

| jīvati | живет |

| tanu | тонкий |

| tanta | струна |

| tapati | теплится |

| tamo | темнота |

| tad | тот |

| tayo | три |

| tala | тло (украинский) |

| tasati | трясется |

| tāto | тато (украинский) |

| tāyati | таит |

| tārakā | зiрка (украинский) |

| tiṭṭhati | стоит |

| tuccha | тщетный |

| te | тебе, твой, тобой |

| tvaṃ | ты |

| thokaṃ | трохи (украинский) |

| dakkhiṇā | одесную |

| dampati | домохозяин |

| dasa | десять |

| dinaṃ | день |

| dūra | далекий |

| deti/dadati | дает |

| devara | деверь |

| dāruṃ | дерево |

| dīgha | долгий |

| dvāraṃ | дверь |

| dve | два |

| dhamati | дмухати (украинский) |

| dhāreti | держит |

| dhītar | дочь |

| dhuma | дым |

| na | не |

| nakha | ноготь |

| nagaraṃ | город |

| nagga | нагой |

| natta | ночь |

| nabhaṃ | небо |

| nava | новый |

| nāmaṃ | имя |

| nāsā | нос |

| ninnaṃ | низина |

| nimbo | лимон |

| nisīdati | садится |

| nīce | ниже |

| nīhāra | снiг (украинский) |

| nu | ну |

| no | наш, нас, нам, нами |

| paṃsu | песок |

| pakāseti | показывает |

| pacati | печёт |

| pañca | пять |

| paṇḍu | бледный |

| patati | падает |

| patho | путь |

| pada | пята, пятка |

| parā- | пере- |

| palavati | плавает |

| palita | палевый |

| palippati | прилипает |

| pitar | батько (украинский) |

| pipphalī | перец |

| piya | приятный |

| pivati | пьет |

| pihā | пиха (украинский) |

| pucchati | спрашивает |

| puṇṇa | полный |

| pubba | первый |

| peta | предок |

| peseti | посылает |

| phalaṃ | плод |

| pheṇaṃ | пена |

| balaṃ | войско |

| bila | берлога |

| Buddho | Пробудившийся |

| bubbuḷa | бульбашка (украинский) |

| bhago | благо |

| bharati | берёт |

| bhavituṃ | быть |

| bhātar | брат |

| bhāyati | боится |

| bhāro | бремя |

| bhūja | берёза |

| bhūmi | земля |

| maṃsaṃ | мясо |

| makasa | мошка |

| makkaṭo | мартышка |

| makkheti | мажет |

| maññati | мнит |

| mati | мета (украинский) |

| mattā | мера |

| madhu | мёд |

| mayaṃ | мы |

| mahant | могучий |

| mātar | мать |

| māra | смерть |

| māsa | месяц |

| miyyati | умирает |

| milāyati | млеет |

| missa | смешанный |

| mutta | моча |

| mūsī | мышь |

| me | мне |

| megha | мгла |

| yuga | иго |

| yuvin | юный |

| yūso | юшка, уха |

| yo | який (украинский) |

| rakkhati | охраняет |

| rata | радующийся |

| ravo | рёв |

| ravati | ревёт |

| raso | сок |

| rucira | лучистый |

| rudati | рыдает |

| rudda | рудой |

| rūhati | рухати (украинский) |

| rohita | красный, кровь |

| lapati | лепечет |

| lākhā | лак |

| lihati | лижет |

| lubbhati | любит |

| lumpati | лупит |

| luḷati | люлька |

| vaka | волк |

| vaṭṭati | вертит |

| vaṇa | рана |

| varāha | вепрь |

| vasanto | весна |

| vahati | везёт |

| vācā | речь |

| vāto | ветер |

| vāyati | вязать |

| vidhā | вид |

| vidhavā | вдова |

| vināti | вить |

| vindati | ведает |

| vīro | герой |

| ve | ведь |

| vejjā | ведьма |

| veṇi | веник |

| vo | ваш, вам, вас, вами |

| sa | свой |

| sakkharā | сахар |

| sataṃ | сто |

| satta | семь |

| sadā | всегда |

| sanku | сук |

| sama | (такой же) самый |

| sayaṃ | свой, сам |

| sarīraṃ | тело |

| sallaṃ | стрела |

| savana | слух; слава |

| saso | заяц |

| sasuro | свёкор |

| sassu | свекровь |

| sātaṃ | счастье |

| sālā | зал |

| sigālo | шакал |

| sukkha | сухой |

| suci | чистый |

| suṇāti | слушает |

| supati | спит |

| suriyo | солнце |

| suve | завтра |

| sūnu | сын |

| sūpo | суп |

| seta | светлый |

| selo | скала |

| sotaṃ | слух |

| handa | айда, гайда (украинский) |

| haṃsa | гусь |

| hadayo | сердце |

| hari | зелёный |

| he | эй |

| hemanta | зима |

| horā | година (украинский) |

Compiled by: Vilāsa Bhikkhu

Świątynia w Dambulli

Kolista świątynia Watadage – Polonnaruwa

Pobierz PDF: Vilasa Bihikkhu: Pali and Polish: Vilasa Bhikkhu language

Zwierzęta i Kwiaty Boga Bogów – jednocześnie symbole Sri Lanki: Słonie ze słoniowego sierocińca (Ceyloński symbol szczęścia – przyjaciel z Bostonu zostawił nam całą kolekcję pięknych figurek bajecznie kolorowych słoni)

Zwierzęta i Kwiaty Boga Bogów – jednocześnie symbole Sri Lanki: Lotos